Working Spaces

For David Shaner and Karen Karnes, two who showed me the way.

Thinking about this symposium and its focus, I kept thinking about place: both the actual places in which we do our work, and the way our minds, like our studios, are furnished with images, quotations, and other presences that provide a backdrop for our making and our aspirations. I suppose this is on my mind because I've been on the move in the past few years. Like any traveler, I am seeing both the places I journeyed to, and the place I came from, with new eyes. After twenty years of full-time studio work, most of it in the same city, I have recently become a kind of Stealth Bomber of education, teaching in universities for periods of three to six months. This has given me a glimpse of a world that studio potters tend to treat with skepticism and defensiveness, born of feelings of frustration and invisibility. I shared that feeling, but the opportunity to be part of a university program came at a moment when I felt restless alone in my studio. I jumped (though not without misgivings) at the chance to be out in the world, and to think about work and clay from another perspective.

My time in the university has certainly stretched my mental muscles and increased my respect for the difficult balancing act demanded by full-time teaching. More strikingly, it has given me a new sense of the ways our work is influenced by the particulars of where we do it, whom we talk to about it, and what we ask it to do. We like to think of the studio as a private place, and what goes on there is, on certain days, solitary, free, and self-directed. There is a quote attributed to John Cage that is tacked on many studio walls, which speaks of the imaginary people in his studio gradually leaving, until finally even he leaves; it expresses our yearning to be totally engaged and in the moment when we work. But our appreciation for that state is flavored with the knowledge that it is rare, that we also work in history, in space, and in a world full of objects that are accorded their meaning by other people. Far from being a free-floating space, the studio - all our studios - are embedded in contexts whose values and structures influence our work and our ideas.

The terms "traditional maker" and "artist-educator" imply a polarity, without illuminating either the common ground or the nature of the differences between these two constituencies in the clay world. For one thing, virtually all studio potters are also educators, whether they teach in the usual sense or simply engage in that never-ending conversation with customers, neighbors, and the UPS guy about what we do, how we do it, and what it is worth. And all of us struggle to find the balance of personal satisfaction, monetary compensation, and outside recognition (however we define that) that will make our work lives make sense. But this struggle is different in a studio and in an educational institution, and I think we are deceiving ourselves to pretend otherwise.

I would make a distinction here between those who are full-time members (or aspiring ones) of a university community and those whose income and work identity come primarily from their studio activity. At the Utilitarian Clay conference at Arrowmont last fall, I was amazed to hear two full-time professors in prestigious clay programs describe themselves as "studio potters...who also teach at XYZ University." This sounds like a different notion of being a studio potter than the ones I know have, but it also, I think, implies that teaching is not their real work, which I strongly doubt in the case of anyone who is a good teacher. If you care about teaching, you know that it is not simply an outgrowth of doing good work; good teaching is good work, and draws on exactly the same reserves of creativity and energy that making does. People in academia sometimes criticize or dismiss as "commercial" work made by studio potters, as though dealing with "the marketplace" means dangerously compromising one's work-without acknowledging the effect that time fragmentation, constant verbalization, and rigid definitions of professional activity have on the work of full-time educators. One world is not better or more "real" than the other, but being a self-employed studio artist has profoundly influenced not only my work but my ideas, just as working and surviving within an academic environment has to have influenced those whose "place" that is, both teachers and students. During my time in the university, I have seen a persistent clamoring among students for clues about how to live out and live on this passion they have cultivated. I think we owe it to them, and to the tradition we are shaping, to think and speak more clearly about the differences among various paths - about the real nature of the choices and compromises we all make.

I want to look for a moment at the concept of the "traditional maker of clay objects," which I think I'm meant to embody here. Tradition is a pretty fluid concept in America today, and maybe always has been, an idea which people are constantly revising or rejecting for their own purposes. I'm not, lately, a full-time maker, and am far from representing the purest extreme of someone who makes their living entirely from the sale of their work. Those who do constitute a large and diverse group which I've found is mostly invisible to the university-based clay world, partly because its orientation is mostly local or regional, but also because its calendar, pressures, and venues are shaped by different considerations than those which operate in an academic setting. (The timing of this symposium, for instance, virtually guarantees that few studio potters would attend, since November is high crunch time if you depend on craft shows, Christmas orders, or a studio open house for income.)

Our view of studio potters focuses on a few, well-known exemplars, a small fraction of all the people making a living from their clay work. Why do we hear so little about the rest? Is it fear of contamination that blinds artist-educators to potters whose work appears too blue, too decorative, too reminiscent of nineteenth-century American stoneware, rather than sixteenth-century Japanese teaware? The work of most studio potters may not be visually distinctive enough (or make the right point) to contribute to an image-rich ceramics agenda. But by marginalizing the voices, concerns, and experiences of people who have aimed their work at a general, rather than a specialized, audience, I believe the "ceramic tradition" preserved and passed on in schools has been distorted.

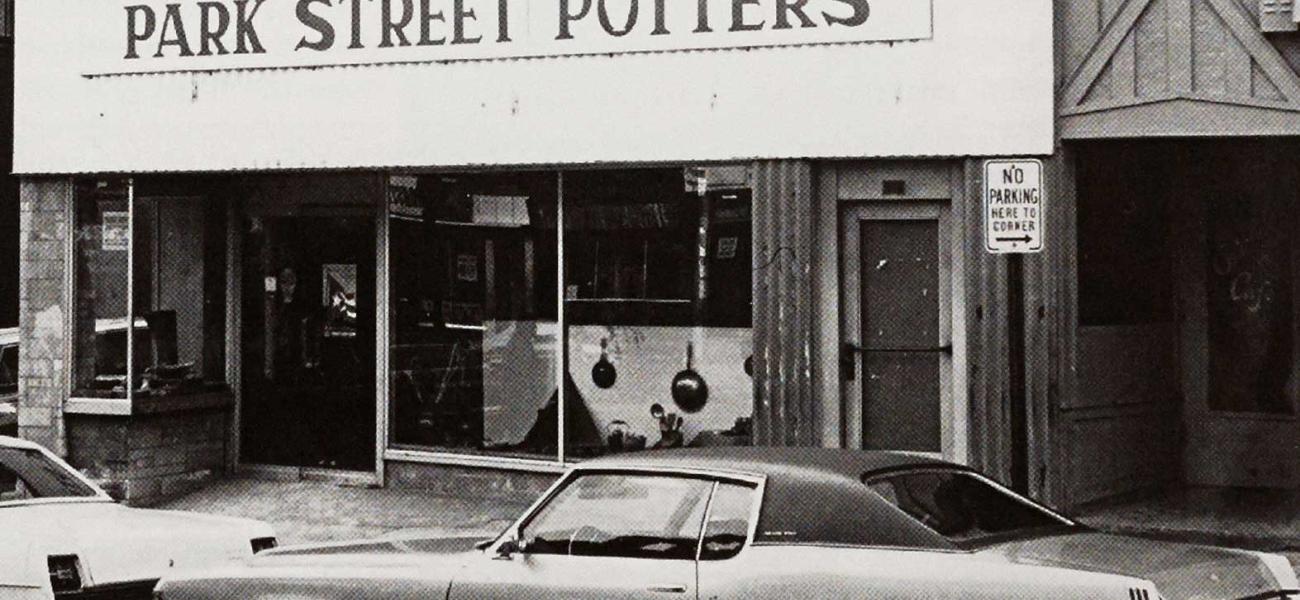

Let me return for a moment to my own work spaces, the contexts that shaped me. When I graduated from college in 1972, I couldn't wait to be done with school: to prove myself in what I thought of as the "real world," and to improve the quality of life there through hand-made pots. I moved to Hartford, Connecticut and opened a storefront pottery with an older friend. Our studio was in an old auto-parts store in a teetering neighborhood, which may explain why we were able to get a small-business loan to help us get started. The meetings at the bank where we presented what we intended to do were, in a sense, my first artist's statement, as well as my first clue that what I was going to be doing was, in fact, running a business. This cast my studio activity in a whole new light, familiar in a general way but miles from what I had been doing at school. The work itself hadn't changed, but the work I was asking the work to do had. I needed to believe, and to convince someone else, not only that I had the skills to make pots, but that there were people out there who would want to buy them. I leapt into this venture feet first with no notion of how much of a beginner I really was, how naive my ideas were, and how much I had to learn. Work habits, serious consideration of function, and the mysteries of marketing were on my course list, along with one of the big challenges of working for yourself: managing the sometimes-exhilarating, sometimes-frightening responsibility for getting the whole operation going every day.

Without realizing exactly what I was getting myself into, I had put myself into a situation where I not only could, but pretty much had to produce a lot of work. I learned by making, the only way to gain the skills and experience that would lead me to work I wanted to do, and then I was forced to deal with what I was going to do with all those pots now that I had made them. In that storefront, I learned that just making good pots was not enough to ensure that they would find homes; I had to actively participate in the process. This involved thinking about who my pots were really for, and how to bring my work to their attention amongst all the objects competing for it. It taught me that "need" and "want" are interpreted, and acted upon, differently by different people. And it started me on a long dance with the concept of value: what is it, how is it conveyed, and is price a realistic or fair indicator of it? The definitive answer to these questions still eludes me, but the questions themselves remain compelling. Taking them on has made that goes on between people and things.

park: a more tightly focused working environment. Here I shared my immediate surroundings with artists and craftspeople working in various media, in a place whose mission was to educate people about "what artists do," as well as to add distinction and class to the neighboring businesses. I was removed here from direct competition with sneakers and other consumer goods. (Though often reminded of them by customers' comments; people would often explain not buying a pot by telling me what they needed/planned to buy instead!) In many ways it was easier to sell my work from this studio, as the people I encountered had more money and were already interested in the arts. In addition I was part of a community of artists, my first taste of the validating and enriching presence of kindred spirits, working separately but along recognizable paths of inquiry.

This arts center was an important incubator for my work and my growth as a maker, but I want to emphasize that, despite the supportive presence of like-minded souls and a built-in arts identity, I was still in a public place, required to interact with customers and visitors, to talk about what I did and absorb their enthusiasm, indifference, or disbelief about it. For my first ten years out of school, I sold most of my work directly, at craft fairs of various types and from my studio, though I did do a little wholesaling. I am well aware that this doesn't work for everyone, and that doing it successfully depends upon a combination of personality, location, and luck. I wearied of it myself, in fact, but cannot overstate the value of the lessons I learned about myself, my work and the world I was sending it out into, from being in direct contact with my actual, as well as my imagined, audiences.

My third studio was in a different factory building, this time back in the city and amongst artists seeking large, cheap space in which to live and work. In this environment I gave up direct contact with the public but gained a different artists' community, one which had little connection to, or knowledge of, the medium-specific aspects of my work. I felt challenged to examine just why, and whether, my work needed to be about the material or the vessel. I showed in fine arts galleries and, it being the eighties, sold most of what I produced.

My "ascent" into the rarified world of the white cube was accompanied by the beginning, for me, of real teaching, at a local community college at night. My wonderful students there, who came from many cultures and spent their days doing many different kinds of work, shared an unquenchable thirst to make things, and gave me a taste of clay's potential for cross-cultural communication. While my own work was becoming increasingly swathed in the language and elite spaces of the art world, I found myself growing more intrigued by the vitality of the nonspecialized conversation about art, craft, and clay that was going on at the college. Unschooled in how they ought to talk about art (and sometimes in English generally), my students challenged me to seek a common language. We found one in that room where the material givens of clay, fire, and process were shared by all, and where an assignment about bowls or houses might generate talk about memories of home or different ideas of what expresses hospitality. The subject of work also came up fairly regularly; many students were surprised to find a potter in a college setting, an anomaly in the cultures they came from. And they wondered what kind of job making pots was, and, sometimes, whether it might be possible for them to quit their jobs and do this wonderful thing full-time. (I said yes, but reminded them that then this realm of creativity and self-determined delight would take on some of the characteristics of their jobs, including tedium, uncertainty about money, and a desire to be recognized.)

I regretfully gave up this dialogue ten years ago, when I moved to a small town in western Massachusetts. I could have a storefront again in this studio, but I have become more like a cottage industry, sending most of what I make to distant markets as so many people do in rural areas. In one way I am compatible with my neighbors here, many of whom are self-employed and work directly with their bodies and physical materials. But for the first time since I began working, my audience is mostly elsewhere, in cities. My work, which to me contains so much of New England's landscape and sense of history, is hard to sell here; people expect pottery to look more "traditional," to go with their eighteenth and nineteenth-century houses. So I have an open studio once a year, go to a couple of retail fairs, and send the rest of my work out to galleries.

In the past four years, for the first time since I received my Bachelor's degree, I have also spent significant time in art schools and university ceramics programs. As a "local potter" I had very little contact with art departments in the places I lived, so I've loved thinking about education and where clay belongs in it, and being around the ways and energy of college-age students. (I still don't get it about body piercing, though.)

Though only a temp in this world, I have gotten a taste of the pressures and assumptions that go with the job. But inner and outer aspects of work are experienced, balanced, and talked about so differently in the studio that some peculiarities of the university environment struck me especially forcefully. Time, for instance, was so fragmented: into class times and semesters (or worse, quarters) - laughably short for introducing, absorbing, and actually working with a technique or topic - and years, expected to represent quantifiable development. The spurts, slow flowerings, and dry spells of my studio work life seemed impossible to translate into the chopped-up, progress-obsessed framework of the academic year. I too had been told as a student that it would take ten years before I made my own pots, and I too had found this unbelievable, after having worked my way up to being a relatively experienced major from my clueless, all-thumbs beginner days four years earlier. Yet it turned out to be true, and to require the making of thousands and thousands of pots, few of them worth a slide or an artist's statement, but each of them essential increments in the process of mastering my skills, digesting influences, and homing in on the work that was truly mine.

The university influence seems most glaring to me in the matter of audience, which I would characterize more broadly as finding a home for our work, or defining what its purpose, in the most complex sense, is. There are many strands to this question - philosophical, technical, economic, and, for the maker of three-dimensional objects, just plain physical. In one way you could say that it has no place at all, that schools are supposed to be free from such concerns, or consider them irrelevant limitations. In fact, the idea that true artists work strictly for themselves is practically in the drinking water in most art departments, and students are rarely asked to give serious, extended thought to defining who or what their work is for.

In another sense, ceramics, having entered the university via the art department, has simply adopted art-world ideas about audience. These are, I believe, profoundly shaped by the concept of the museum as an ideal space: separate from daily life, from visual distraction, and from the passage of time. This is such a widely- held and deeply-embedded aspect of our view of objects that we rarely think about it. Few of us would say that

we make our work "for" museums, yet most gallery environments are patterned on museum spaces and share with museums an implication that they are above, beyond, or in some way unconcerned with time and commerce. Doesn't a beautiful, spare, tasteful and well-lit room seem to most of us the most respectful and enhancing environment for our work? Asked to choose between a favorite piece being purchased by a museum and being bought by someone who may break it, grow tired of it, or put it next to some awful paperweight inherited from their grandmother, who among us, functional potter or sculptor, would not feel flattered and tempted by the prospect of joining the company of "best things," becoming part of our culture's art history, and transcending time?

That universities and museums operate spatially and philosophically apart from "the real world" is not in itself problematic, but it skews the teaching of ceramics in a particular direction, and saps the learning of a fruitful engagement with complex issues that face all artists, but potters in particular. Form, meaning, and quality (and is that the same as taste?) intersect differently in different media, and in different contexts. When students decide that function is not a primary concern in their work, or that they want to draw on traditional forms in non-traditional ways, the work would be stronger for having honored and grappled with all the issues raised, rather than acting as though they don't really matter. Do a teapot and a "teapot form" mean the same thing? The Red Queen-like freedom we think we gain with that bit of linguistic fudging runs the risk of making words meaningless, unhooking our work and our thinking from a more general understanding of what objects mean, what they do, and what they are for.

Are galleries the best or most appropriate context for our work? Is selling your work part of having a career, or is it somehow, sometimes, at odds with it? Teachers, especially young faculty, are under a good deal of pressure to exhibit their work and demonstrate "professional activity." With so much at stake, few can afford to ignore the department's or division's definition of what constitutes professional. A successful studio sale, participation in the Philadelphia Craft Show, or a large commission might represent appropriate and challenging venues for their work, yet not register where it counts, whereas an exhibit in a university gallery will leave the proper paper trail. Teachers, like other artists, want to be in their studios, and show obligations are a time-honored way for busy people to make space for their studio work. But all this professional activity can sidestep the issue of who the work's real audience is and how it comes across. While learning to take good slides and applying to juried shows, thus generating lines on their own resumes, students may work on their careers without addressing some of the fundamental questions and options that await them when they leave school.

The thing is, it's possible now, maybe for the first time in history, to make "potter's pots" almost exclusively: pots that are about the traditional concerns and uses of pots, but address primarily other potters, teachers, and collectors, and not the general buyer or user. When I was in school, the explosion of programs, galleries, and publications was just beginning; the clay world then was more like a tribe than a field. In the years since, art departments and ceramics programs have boomed. In an essay called "Can Poetry Matter?" Dana Gioia writes of a similar explosion in poetry:

Decades of public and private funding have created a large professional class for the production and reception of new poetry, comprising legions of teachers, graduate students, editors, publishers, and administrators... The energy of American poetry, which was once directed outward, is now increasingly focused inward. Reputations are made and rewards distributed within the poetry subculture...As Wilfred Sheed once described a moment in John Berryman's career, "Through the burgeoning university network, it was suddenly possible to think of oneself as a national poet, even if the nation turned out to consist entirely of English departments.

Students looking out at the world beyond their schools can now see a profession, with recognizable steps to advancement and numerous opportunities to continue the discourse they began in college, either in graduate school or in a growing number of residency programs. These programs allow young artists not only to continue working, but also to continue feeling reassured that they are artists and are doing something that makes sense. But the specialized and supportive nature of such places can also postpone crucial encounters by perpetuating the same values and assumptions that operate in art departments. Surrounded by people who already know what a ewer, a Shino, or an anagama is, one may never question whether these words communicate anything useful to non-ceramists, or where one's work belongs in the world. The clay community, which is such a striking and appealing aspect of ceramics departments, has expanded into a national community, organized around institutions and providing support and opportunity to people at all levels. Even at the undergraduate level, students often construct for themselves a map of this community- of hot schools, good galleries, and prestigious craft programs across the country, while remaining ignorant of people working in their medium just beyond the campus gates. Success means getting into shows, maybe having one's own gallery show, getting grants and working at low-paying jobs while trying to climb the next rung. The hero-artist who works only for himself, disdaining any consideration of sales, remains enshrined in many a graduate's mind, while the marketplace-other than the art market of galleries and collectors - is feared and avoided for its toxic influence. By defining success and the artistic high road in such narrow terms, are we really helping our students? By encouraging them to believe that serious consideration of other people's tastes, desires, or economic circumstances will prevent them from doing "their own work," aren't we making marginality a self-fulfilling prophesy and providing fodder for the statistics that predict that few art students will be engaged in any art activity five years after graduation?

Or is that a bad thing, a mark of failure on the part of the university? I sometimes wonder if the world really needs more artists as much as it needs more people who appreciate mindful practices, whatever their products. Perhaps we need to question the assumption that teaching's most deserving recipients are the future professionals in the field, and to expand our definition of success so as to include more visions of what "making it" might look like. At the same time I think we need to articulate a broader idea of the educational use of ceramics, in the curriculum or in the "real world."

Many years ago, I had an experience that taught me something about the lives pots begin when they go out into the world. A woman who had been buying my work for years came to my studio in search of a wedding present for someone very important to her. Because she liked my work so much, she felt she would be able to show her appreciation in two directions by giving one of my hand-built pots to these people, and so she spent a bit more than she had budgeted to buy a piece she really liked. About a month later I got a call from the couple, wondering if they could return the pot for a refund. I'm pretty sure they hadn't understood, until that moment, that they would be talking to the actual maker; they clearly didn't like, value, or "get" this object, and it had completely failed to convey either its own specialness or the specialness of the giver's feelings toward them.

The emergence of the university as the keeper and transmitter of clay traditions has enriched and enlivened our medium in many ways. It has brought some exceptional people to the field and has introduced hand work and hand-knowledge into the arena of ideas about the structure, nature, and purpose

of higher education, a pretty interesting place for a supposedly traditional craft to be. In addition it has brought to learning about clay a greater awareness of its own global history, as well as its connection to, and/or distinction from, other forms of human art-making. My recent time in academic studios has been enormously stimulating, challenging, and rewarding for me, giving me a new appreciation I of, and interest in, I what's going on in those hallowed halls. But though I understand now why it's so hard for teachers in universities to reach out to potters in their surrounding communities, I think students want and need more real dialogue and more varied models for how to live their lives as artists. Few will go on to get the college teaching jobs that have been their teachers' way of building a professional life for themselves. And in any case the uses of a ceramic education are more varied than such a path would suggest. The narrow definitions of professionalism and success that pervade university culture do a disservice to students and makers, with other visions of their work and their world. In or outside of the university, I want to imagine for our work as wide a sphere as possible: not just the museum but the dishrack; not just shoptalk, satisfying as that is, but the whole messy conversation.