Words About Words

I don't really know when I became attracted to words as a means of expression in visual art. Although I come from a family of readers and academics - my mother and brother devoured books each week and my grandmother had a degree in library science – I resisted books and reading for the most part, keeping to National Geographic and the occasional newspaper. After college, though, when starting on a path studying art, I found myself with a library card in my wallet and a reason to use it. Reading became a vital part of my studies, supplementing my learning in the pot shop. My new knowledge about what it took to physically create, as well as the ideas I explored through books, greatly colored my world. I started thinking of all visual communication - including the written word - in new terms.

It was a long time before my art-making and words came together. However, in my early explorations, I recognized that much of contemporary art is conceptual - that is, about ideas and questioning rather than recording, documenting, or pleasing. For better or worse, I feel a part of this movement. Discovering something previously unknown, if only to me, or doing something in a new way, are prime motivations.

As idea-based as our art-making may be these days, the printed word still carries authority for me, lending credence to an idea. Something written is real, the idea made physical. Furthermore, I find that attempting to put ideas into written form refines them, occasionally leading to deeper insight. Finally, within my psyche, making ideas physical trumps the most eloquently verbalized thought.

As I got my hands working and my head spinning, I marveled at artists such as Jonathan Borofsky, who captured my imagination with his piles of handwritten counting and stories scribbled on the walls of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It was there also that I first encountered the works of Marcel Duchamp such as The Bride Stripped Bare, and a display case of drawings, notes, and letters. These works came to me largely as a complete shock and mystery; what little I grasped about Duchamp's work were his "readymades," taking commonplace objects and reconfiguring or placing them in a new context. In the information age, where ideas prevail over objects, this made so much sense to me.

My head loved the idea of readymades, but my hands hadn't a clue, so I stuck to making ceramic sculptures in the traditional vessel-based vein. In graduate school (and, to be completely honest, by accident), words finally found their way into my art-making. I was rolling out slabs on newspapers, which transferred some of the ink to the slab. Here was my readymade, in a new context! Curiously, only some words transferred, altering the meaning one could take away and leaving holes for the imagination to fill. This gave me the idea to erase some words by sanding the clay, thus taking a newspaper story, repositioning it onto clay, and manipulating the physical object. This was the beginning of my exploration of word-as-ceramic art.

Since then I have developed methods of working with printed words and imagery in ceramic books. I believe that my finished product, a fired ceramic object, is as true a book as any made from paper, wood, or animal skin. The one quality I love about all non-electronic books is their ability to show their handmade origins or hand-changed history; even today's mechanically produced books on paper show the wear and tear of their use. As many of us have discovered, certain photocopier or laser printer toners contain metallic oxides like iron or manganese. When fired, toner can leave a beautiful light-brown-to-magenta image on the clay. This warm imperfect effect of the toner transfer helps align my books with traditional ones.

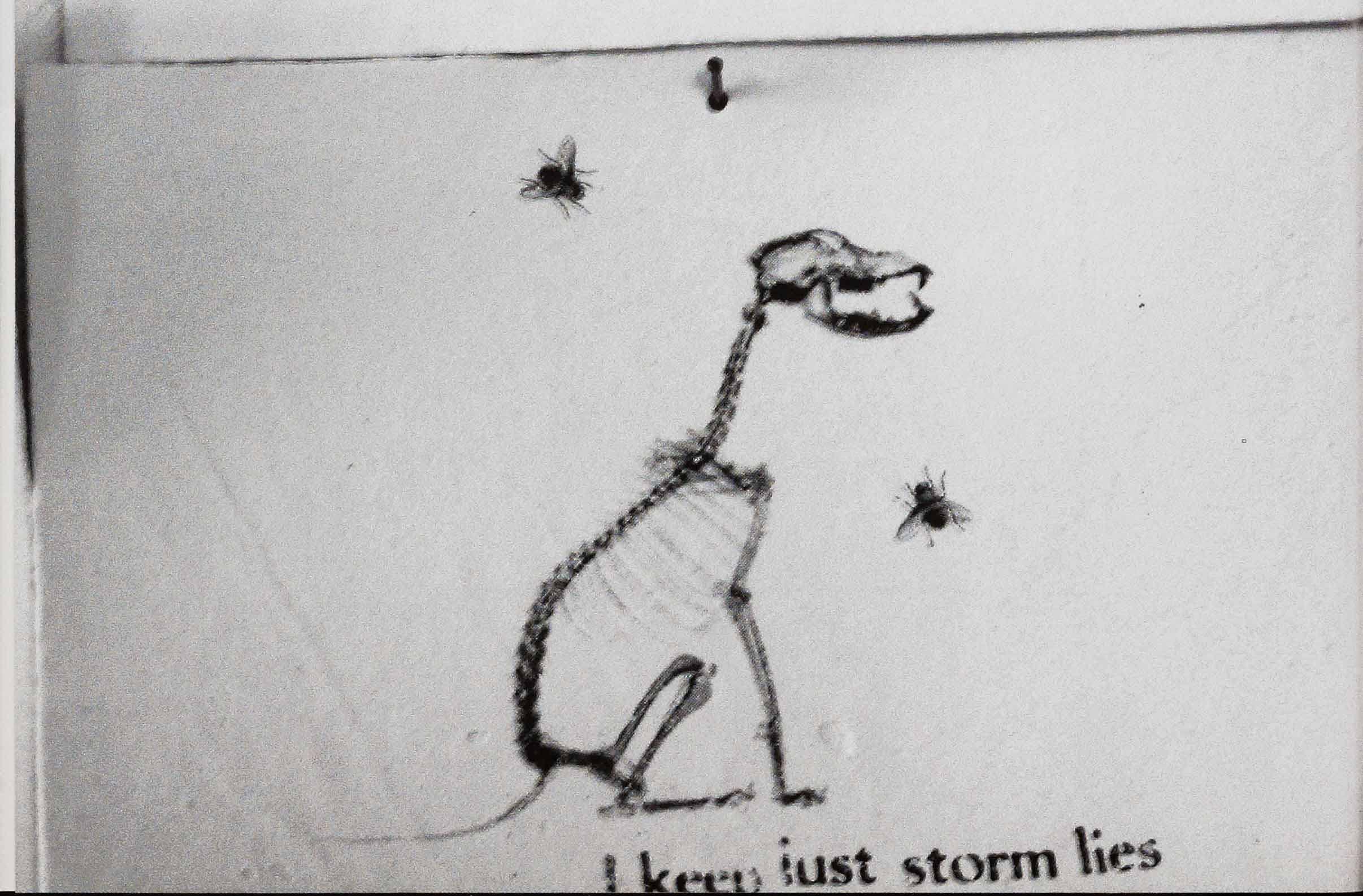

In general, my working method is pretty straightforward, though laborious. I begin with my own writing, usually a prose poem or paragraph of narrative fiction. Guided by the gist of the words, I select a typeface to fit and print out in many different sizes, styles (bold, italic, roman), and orientations (forward, backward, vertical, and horizontal). I print many dozens of these sheets. Because I work in sets, three to six books at a time, I prepare by casting out thin sheets of cone 6 porcelain and cutting pages down to size with a straightedge and matte knife. Then I lay out the blank pages on a tabletop and begin the task of cutting out words and arranging them across the pages. Typically, each book has between 48 and 64, 4"x6" pages. I've come to think of the pages as both linear, read sequentially, and flat, reading as one large poster or image. Often, I've collected images from Internet Google searches, dictionaries, and old magazines that echo some notion in the words. These images are arranged within the book, too. After transferring the toner to clay, (I have used both direct methods with solvents and the now-common water-lift decal paper) I stack the pages, dusting each with some separating agent. Placing the raw book into the kiln is a very important part of my process. I place the books over bits of kiln shelf or other refractories to allow the pages to bend, slump, and tear during firing. I'm happy to relinquish control at this point.

For me, art-making is about learning to undo social, political, cultural, visual, and grammatical rules and finding new, or at least unconventional, ways to express my feelings, questions, and ideas. While attempting to undo these covenants, I've come to appreciate those who have broken them. Often, setting up a context in which chance plays a part is the key to making the breakthrough. Pollock employed chance with his drips, and Voulkos certainly employed then-unconventional methods of ripping, punching, and stacking clay to dare gravity's effect. I like to invite chance elements into my work. I take my writings, which I think I understand, cut up and rearrange the words, fire them (allowing for chance bending and fusing in the kiln), and find a work altogether new. Through the process, those original readymade words become something else entirely - or perhaps they simply reveal what was hidden.

Probing the unknown is exciting. I try to work without too much conscious intent (I get lost all the time), and to produce something that isn't immediately obvious to me or the viewer, something that needs rereading. Joseph Cornell made collages out of knick-knacks, found objects, wood, paper, glass, toys, and words. He was very interested, as was Duchamp, in hidden meanings in both visual and written vocabularies. Both artists greatly enjoyed puns, double entendres, and similar play with words. This, too, is part of the game for me - teasing out those double meanings, or hiding a phrase with backward printing. As new phrases resolve themselves; others recede. "The buzz of flies" becomes "the buzz of lies." In another case, after firing, "In fall's last/copper rain/I storm in" revealed itself as some sort of visual/written Rorschach test. Freud would have a field day.

I like the idea of meshing a visual and a written vocabulary into one story, to hint at meaning through several nuanced levels. However, I feel that a book is most successful when it leaves enough out - engaging the reader to fill in the blanks with her own experiences, thoughts, or feelings. In the end, my books help me to reflect on what I'm thinking and doing in the moment, and then to relive the story and see if my imaginative understanding still holds true.