Wives

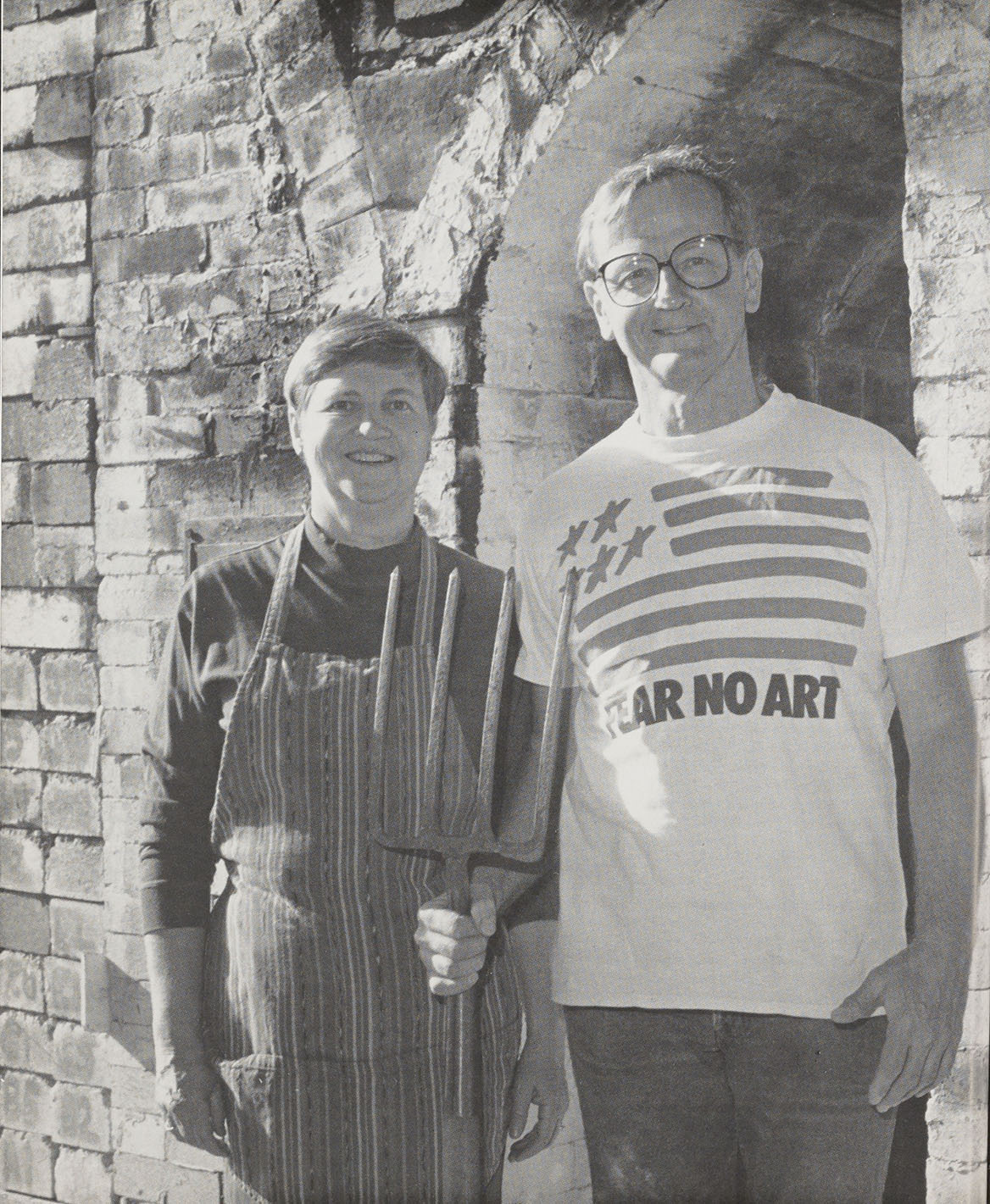

Ann Shaner

"Being a potter is somewhat like being a farmer," Dave Shaner, my husband, casually commented some time ago. I thought about the how and why of these two ways of making a living. I grew up on a farm in Pennsylvania where my father was a farmer and my mother a homemaker and helper. This childhood environment helped me to recognize the similarities.There are commonalities: a cyclical work process, seasonal demands, working always with a risk of the outcome, sporadic income, long hours, the work ethic based on self-motivation and self-discipline. Less obvious commonalities are the working together of husband and wife, with a genuine need to assist each other.

My role as a wife has been varied and changing, beginning at Alfred University where Dave enrolled as a graduate student shortly after we were married. I had majored in elementary education at Kutztown University, Kutztown, Pennsylvania, where Dave and I were classmates, and we both taught in the Paoli area schools. I had a summer job teaching at the New York School for the Blind Camp at Cornwall-on-the-Hudson, but my New York teaching experience ended with the birth of our first son, and mothering and homemaking took preference. My part-time job as an evening library assistant while Dave cared for the baby helped us squeak by financially for the remaining months at Alfred.

When Dave completed his MFA degree, we agreed that we could be happy anywhere his job took us. During four years teaching at the University of Illinois (1959-1963), Dave set up a wheel and small work area in the basement of our house. He found satisfaction for that growing desire to have his hands in clay.

I began packing a few pots for shipping and keeping a set of income and expense records. We planted our first garden, the family grew, and Dave dreamed of devoting full time to clay. He was concerned about getting too comfortable and financially committed to make a break from teaching.

Several trips to Montana to touch base with Ken Ferguson at the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena drew us to the reality of a move West. There was intense deliberation and lots of fence riding for both of us. Would we choose the dream of a potter's life with its unknown risks and intangible successes and benefits? Opportunity was knocking and the decision was made. We were off for Helena – three children, a dog, and belongings that included an electric blanket for those cold Montana nights, a parting gift from friends.

Our seven years at Archie Bray (1963-1970) were filled with challenges, excitement, and plain hard work. Dave sensed that if he worked hard somehow the Bray would succeed and his work would grow. While Dave was deeply involved with his work and the enormous task of running the business, I found myself picking up the loose ends. I greeted visitors, sold pots, cleaned the sales gallery, and constantly watched for shipping boxes as I ran other errands. On the homefront I was there for the children. I packed lunches, helped with homework and was involved in the myriad activities of preschool and school-age children.

The close proximity of Dave's work to our home gave new dimension to our lives. His work allowed a close relationship with me and our children. When the bread came out of the oven, I sliced some for Dave and others working there. Hot tea was a survival tool for stacking a kiln in the unheated, below-freezing kiln area just thirty feet from the front door. More pots needed to be packed, the checkbook balanced, and lunch prepared for the unexpected visitor who stopped by the Bray.

My admiration of Dave and his commitment to his life's work heightened. An emotional intimacy surrounding his work expanded. We loved the Bray. Our children speak of it affectionately and in special ways: the trees they assisted in planting and watering, spending time in the pottery with Dave, and meeting many potters who became their friends. We loved Helena, the area, the people. We discovered a sense of place in the West.

Seven years seems like a short time; however, it was time to move on, to be on our own, to leave this wonderful place to another's energy and vision. The financial risks and the thought of re-establishing roots made our decision difficult, but in the back of our minds we knew we were ready to establish a place of permanence. That need to find a place for our home and set up a studio for Dave's full-time devotion to clay was influenced by a writing by William H. Murray:

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy/the chance to draw back. Concerning all acts of creation, there is one elementary truth ... that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would otherwise never have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision raising in one's favor. All manner of unforeseen incidents and meeting and material assistance which no man could have dreamt would come his way. 'Whatever you do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, magic, and power in it.” – Goethe.

The planning, building, and moving were all-encompassing. Doing many tasks not part of one's area of confidence was difficult. I remember the relief and good feeling when Dave finally made pots again. Now, twenty-one years later, we look back on that year and wonder how we accomplished this. It had to have been our commitment and relative youth.

These two decades of living in Bigfork (1970 to the present) have truly been years of standing together. As I look back at my involvement in Dave's work, it appears as a crescendo, each year adding a need or two.

The seventies proved to be a time of total family effort. Preparations to transform Dave's studio into a place for display each November for his annual home sale drew our energies. I chose to teach in Bigfork Elementary School. Each of our four children made contributions, varied in each one's own way, in support of Dave's work. Their childhood experiences in this creative environment enriched them; our sons now work in the hi-tech field, our daughters in human services. The family relationship continues to be important to us. When our son was seriously injured and Dave found it difficult for his work to flow, he began picking up my loose ends and shared more home responsibilities.

As the children entered college, my focus turned even more toward Dave, his work, and our time together. In 1986 Dave's back surgery made this focus a necessity. When he was back in the shop after several months of recuperation, I assisted as much as possible. We found ourselves lifting together, sharing the physical load. Dave spent less time on the wheel, increasing the time hand-building with coil and slab construction. Four hands made some pieces go together more smoothly. I gradually became a holder, a coiler, a helper, and discovered the joys of touching clay. When his recovery was complete and that need ended, the comradery of working together was so satisfying that it had taken hold. I chose to assist as much as my teaching allowed.

Throughout the last thirty-four years there have been many bonuses. On some occasions I travel with Dave to workshops. These are my times for relaxation, renewal, and making new friends. It is with much pleasure that I cook and serve with fine pottery in the kitchen. Our home is filled with other potters' pots. Living among them and knowing some of the makers is a privilege. The potters' world is a small world, and living with Dave has given me the opportunity to be a part of the interaction and fellowship of potters.

I now know the rewards of the path we have traveled. In Dave's work and mine we have come to live as Michelet, a French historian, said: "The end is nothing, the road is all."

Gertrude Ferguson

Ken Ferguson works at home when he is not teaching ceramics at the Kansas City Art Institute or giving workshops. I am at home most of the time, too, and can observe just how deeply he is involved with his job; it is always within reach. He has maintained, for almost forty years, enthusiasm and seriousness about ceramics, about education, and for all the professional and social contacts that the job requires.

He is as interested in the people as in the creative work. From his desk and telephone he is continuously in touch with students, former students, and colleagues. There is always new information to

pass around. Ceramic artists create a unique support system by freely and openly sharing knowledge, and Ken has always been an active participant in it.

Ken has a spectrum of interests aside from work, and they, too, are never far from his reach. They range from his favorite recreational outlets of music, sports, films, humor, and a vast personal correspondence to keeping up with the current news and history, and always an intense concern for the arts. If he cares for a subject at all, it is likely to become a consuming interest. It is hard to tell where his extracurricular life leaves off and his professional activities begin. They merge, and it seems inconceivable to him that they might be separated. Teaching, research, creative work, recreation, social life, home life, and family life are integrated.

Given such varied interests, he is a hard person to keep up with. But, because so much of his activity is generated at home, I am more or less drawn into it. When our children were young, it was less. Ken had his work while I had mine of rearing three children – and gratifying work it was. There was nothing else, at the time that I should rather have been doing. Having their father's work so much in evidence all around was an aid to their upbringing, and so was his presence. It made us all aware of what it took for him to earn a living.

During those years, Ken undertook major building projects, first in Wyoming and later in Kansas – a home and a studio at each location. We all helped in the construction and, for all of us, building became second nature.

I have continued to do minor building and repair jobs in the home and studio. I tell myself that property maintenance and day-to-day homemaking are equivalent to an occupation. Any outside employment for me has been short term, a year or two, now and then, or substitute teaching. I never returned to my early work as an art teacher in public school. At present, with my family grown and away, there are no great unscheduled spans of time. But there is more time than there used to be, and I have gradually become involved with the pottery business.

My first direct assistance to Ken's career began only recently when I started to take care of shipping his pots to galleries. They are a challenge to pack and ship safely because of their intricate detail and great size. Often, instead of elaborate packing, I take the work by car to its destination. Paper work and some of the color slide organization has become partly my responsibility, too. In the studio, I look at his work and discuss it with him if he asks, but he hires ceramics students when he needs help with the clay or kiln. In the creative realm, he works alone.

I enjoy some interests of my own: reading and drawing are the most available because they can be done by myself, almost anywhere. I am comfortable doing things alone. A few classes in visual arts and in education have been rewarding for me – not yet a serious pursuit but it could be. Keeping in touch with the family is important; they visit regularly.

I deeply appreciate the natural world. I like painting, sculpture, architecture, the crafts, old and new – anything made or done well is a pleasure and of great importance to me. I like to travel, especially on long car trips. Glimpses of other environments and other cultures are valuable, and the experience of the journey itself is satisfying. We have been fortunate to have taken fine trips both here and abroad.

I share some of Ken's interests, but unlike him I prefer to separate activities, giving time to each. I do not shift gears easily and swiftly between subjects as he does. Ken's talent for sudden, intuitive shifts is effective, and that is how he covers so much ground.

We are different! There have not been, however, serious conflicts over directions taken. It is not always by intention, but just as often by accident, and for separate reasons that we agree to make an important move. For example, in the beginning of his career a key decision for Ken was to pass up a safe teaching job and take a position at a (then) little known foundation for ceramic artists in Helena, Montana. He knew there would be a studio and a kiln in which he could make pots immediately. I was satisfied anticipating a new life in the Rocky Mountains. I was motivated by a spirit of adventure while Ken was looking for opportunity.

The mountains were all I hoped for. It was a splendid environment for raising children, too, and that was what my adventure turned out to be. We had arrived in Montana with one small child and left six years later with two more. For Ken, the Archie Bray Foundation lived up to its promise as "a fine place to work". He developed his skills there and laid the groundwork for his career in ceramics. Each of us retained our individuality. Individual preferences, ideas, dreams, and goals are necessary, but differences need also to be recognized, valued, and developed insofar as it is possible.

We have had the traditional marriage in which husband earns and wife cares for the home. Male and female work roles today are not so clearly defined. Recently I heard an astronaut's wife say that while men give material support, the support they receive from women is a great gift; they receive the permission and freedom to explore, to discover, to become whatever suits them best, knowing that the women are caring for homes and families. That rationale is satisfactory up to a point: the freedom to develop an occupation that sustains one's interest for forty years is a fine gift, but so also is raising a family. Ken Ferguson explored, and discovered that he was an artist with a talent for working with clay, and another talent for working with people. But I cannot say that it was because of permission from me or anyone. One gives oneself permission. He had extraordinary drive, energy, and instinct. Nothing could stop him!

I can say I have lived with a person who successfully combined his artistic and social needs with the necessity to support a family, and he has not compromised artistic principles, nor failed to provide well.