Teach Them to Fish: Thoughts on Charity and Reciprocity

The Salt Ladies of Senegal

“Senegal is a food-deficit nation, but produces a surplus of salt. The problem is the salt is not fortified with iodine, and Senegal has an epidemic of iodine-deficiency disorders, such as goiter, which inflicts lasting damage on children's minds and bodies. The World Food Program decided to purchase all its salt from 7,000 village producers in Senegal and give them the tools to iodize the salt. The result is a true win-win-win. The women have a steady income, we get iodized salt for our programs, and they also sell iodized salt now to their villages, helping to fight the disorder. An example of helping local people to help themselves, safeguarding always the personal dignity of those we serve.”

--Excerpted from a statement given during a press conference by the World Food Program's executive director, Josette Sheeran, in 2009.

I recently met a girl who, at seven, was wise beyond her years. On the topic of hunger, she noted first that she herself had gone to bed with a full belly last night. She followed that statement, with "If we who have food and a family do not feel happy, why should the kids who don't have the basic stuff even want a better life? I have my mom and dad, my own bed, and food; I'm very happy."

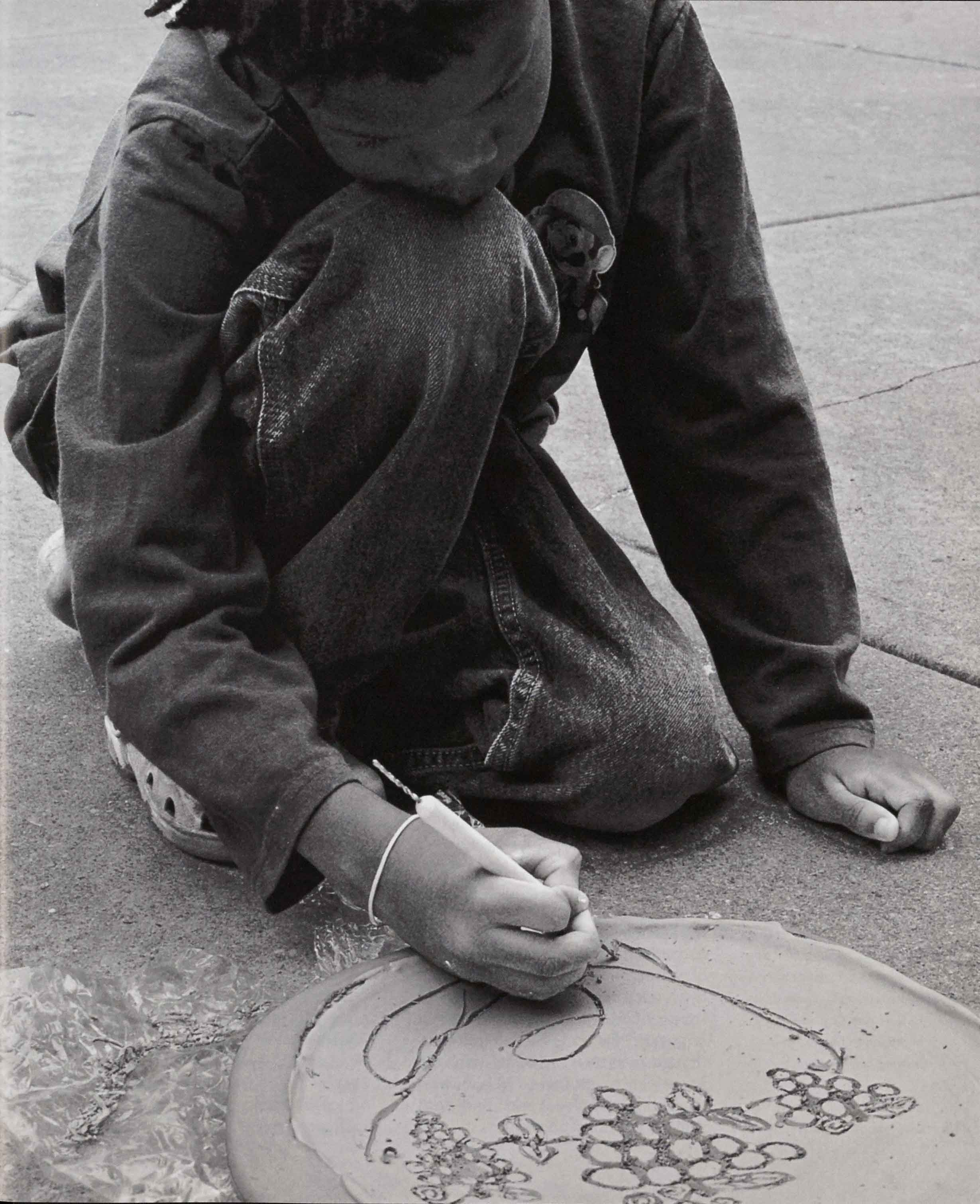

We were drawing on plates while we talked. I had been recycling clay from an installation I had done recently in Philadelphia and using it to make plates. I invited children to draw on the plates, which were then sold at a fund-raiser to improve the quality of food at a homeless shelter in Philadelphia.

I remember when I was seven. My grandfather insisted on his independence. He hated the thought of using food stamps. He spat the word welfare in disgust and made do, shooting squirrels if he had to and using newspaper in the outhouse. Yet he was always the first to give around the community. Cash-poor, he spent his great wealth of other resources, looking in on elderly and disabled neighbors and teaching kids to fish and hunt responsibly, to grow and can food, and to tie sound knots and build things. He distributed leftovers from our meals to those who were ill or who just needed a little help putting food on the table. Later, when he was forced to rely on Medicaid to pay for hospice care, we hid this from him. Injury to his body was bearable, to his pride was dangerous. My grandfather was a great giver, but a terrible receiver. I am learning that sustainable systems require both.

I have been working on a project about hunger for two years. It began as a design for an active installation that uses geophagy (eating clay) as a launching point for a visual poem about need. Then, I was invited by The Clay Studio to produce a new performative piece in conjunction with the 2010 NCECA conference in Philadelphia. With this official commission, I was able to further develop the project and make it site-specific to that city.

I worked at food-distribution centers and homeless shelters across the city to conduct my site research, and found that highly processed, preservative and sugar-laden foods are most often donated - and most popular. Questioning what my small project could realistically collect in donated non-perishables, I grew increasingly concerned that this effort would be so comparatively small and its distribution so fast that the families receiving it would be hungry again the next day.

As I sought a more sustainable solution, I began to notice a vibrant urban farming movement all across Philadelphia. Throughout the city I met farmers who are concerned not only about food quality and fresh-food accessibility in low income urban areas (sometimes known as food deserts), but also about the availability of culturally appropriate food. Urban farmers challenge Philadelphia's blight by providing both farm education and fresh fruits and vegetables where they have been absent.

To reflect this grassroots response to hunger and food insecurity, I built a mobile "education garden" for the upcoming exhibition. This garden would be a tool for fostering self-sufficiency, community engagement, and improved food quality. Gallery visitors could eat together and discuss the issues raised by the rest of the installation. At the close of the show, the garden was to be relocated to Stenton Manor, a homeless shelter in a struggling neighborhood. Stenton's brand-new Hope Farm (the shelter's sole source of fresh produce) was at that time preparing for its second growing season, and the education garden could directly engage the surrounding community: the waist-high mobile units allow neighborhood senior citizens, whether wheelchair- bound or simply unable to kneel on the ground, access to plants. These seniors visit the shelter and help teach the children living there about growing, harvesting, and preparing food. The enrichment runs both ways.

Phase II of the project was the exhibition Hunger, Philadelphia at the Painted Bride Art Center, in the Old City neighborhood, near The Clay Studio. The main floor of the gallery housed a banquet table piled high with clay casts of local vegetables, set in a landscape built of locally dug clay. Clay-covered live models ate clay vegetables while a soundscape emanated up from the bowels of the building along with the enticing smell of baking bread. The upper level housed the garden, where viewers were invited to eat ripe vegetables right off the vine. At the close of the exhibition, the garden was relocated to Stenton Manor. Excited children encircled us as we unloaded the trucks, and we had to stop and rope off the area to avoid accidents. I promised to return in a couple of months to teach them how to draw the food they grew, and then I began planning Phase Three.

The final stage of the Hunger project began when I de-installed the exhibition. A half-ton of the clay and sand I used was donated to Stenton Manor to build a bread oven. The resultant yawning turtle-shaped oven baked and served its first loaf three months later. The rest of the clay was recycled into plates on which children from the shelter (and children in other regions, on behalf of the shelter children) made drawings of foods from the garden.

An exhibition at The Clay Studio called Earth to Table opened with a sale of the decorated plates. Project supporters offering a $100 donation received an original drawing about quality food, on a plate made from locally dug clay. All the proceeds were invested in building a greenhouse at Stenton Manor so that residents may farm year-round, improving the quality of the food served to children and their families while also engaging minds through farm education.

Last month, I was drawing with a family on plates for the fund-raiser. This family is struggling but not destitute. The threat of poverty is a constant in their lives, and some days the grind is really hard. We talked as we drew: about kids living at the shelter, about hunger, and about helping children develop tools that build self-sufficiency As I watched the same sequence unfold -

lack of confidence in their drawing skills shifting to pride - I saw that Earth to Table wasn't just teaching this family about drawing, it was also setting an example for the children, of giving to other children less fortunate. And it was brightening the parents' outlook: their daily worry was momentarily dispelled as they began to feel able. The father told me this project was a glimmer of hope. The world he knew brimmed with discouragement. It was not that they hadn't wanted to help those less fortunate, but cash-poor and incessantly worried about their own plight, they just couldn't process the needs of others while barely meeting their own. The Hunger project allowed them to give in the only way they could - in a non-cash form. These drawings, a form of currency that would better the lives of families struggling harder than they, were a source of pride.

Presently, I define charity as an offering at arm's length. There is a stigma attached to accepting handouts that degrades the morale of the poor. For some, it's downright embarrassing. For others, the feeling of shame simmers, fueling apathy, anger, resistance to change. The Hunger project seeks instead to build mutually beneficial relationships. I am a student of the work I make, guided by research and interested in connections between people. Once, during this project, a wise friend told me that eating alone is worse for one's health than smoking. While I am usually careful about the source and the stuff of my food, I am guilty of cradling the phone on my shoulder and eating an apple with one hand while pouring molds with the other. I eat en route and I eat for fuel, not because I enjoy food. The Hunger project, at its heart, is a farming-feeding circle, connecting people to one another. New friends in this circle spend the day growing food, and the evening preparing it. After all this effort, there is no skimping. An invitation to join means sitting down to talk, eating together, appreciating the quality of the meal. Similarly, drawing with kids is a timeless pause, and a chance to see the world through someone else's eyes. A lifelong student finds education everywhere; looking is learning. It is in the looking that I locate my sense of wonder, and in gaining new perspectives that I receive sustenance.