Tea, Torture, and Reparations

Marking the twentieth year since the opening of the notorious Guantánamo Bay detention camp – a United States military prison used to house Muslim men who were alleged unlawful combatants – artists Aaron Hughes and Amber Ginsburg created 780 cast-porcelain Styrofoam teacups to address Guantánamo's human rights violations. The project is a symbol of solidarity, awareness, and protest. Each porcelain cup is a creative response to the act of resistance by people imprisoned at Guantánamo, whose only means to express themselves, under the weight of systematic torture, was to draw on the surface of their day-to-day Styrofoam cups.

Marking the twentieth year since the opening of the notorious Guantánamo Bay detention camp – a United States military prison used to house Muslim men who were alleged unlawful combatants – artists Aaron Hughes and Amber Ginsburg created 780 cast-porcelain Styrofoam teacups to address Guantánamo's human rights violations. The project is a symbol of solidarity, awareness, and protest. Each porcelain cup is a creative response to the act of resistance by people imprisoned at Guantánamo, whose only means to express themselves, under the weight of systematic torture, was to draw on the surface of their day-to-day Styrofoam cups.

The detention camp opened in 2002, following the start of the "Global War on Terror." It has held roughly 780 imprisoned men and is strategically located at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba, which is outside of U.S. territory. This geographical circumstance enabled U.S. military leaders to avoid the Geneva Conventions, a series of treaties regarding the treatment of international civilians and prisoners of war. The camp has been condemned repeatedly by international human rights and humanitarian organizations[1] for human rights violations, including the use of various forms of torture, sexual degradation, and forced rectal refeeding while prisoners were interrogated. "Between 2002 and 2021, nine detainees died in custody, two from natural causes, and seven reportedly committed suicide."[2] As of March 11th, 2022, thirty-eight men are still extralegally imprisoned, nineteen are recomended for transfer, yet remain imprisoned. Of the men who are currently imprisoned, twelve are charged with war crimes yet continue to await trial after 20 years; two have been convicted and ten are still awaiting trial. In addition,"seven detainees are held in indefinite law-of-war detention and are neither facing tribunal charges nor being recommended for release."[3]

The legal quagmire of the men who are currently imprisoned is complicated, to the point that standard legal terms begin to fail. "Suspected terrorists," "unlawful combatant," "prisoner of war," or "detainee," Ginsburg works to lend context, "We no longer use the term detainee, but rather, a person who is or has been detained or imprisoned." The term "detainee," rather than "prisoner of war," is what released the U.S. from wartime conventions. "The language of 'militant' and 'terrorist' haunt the lives of the men who were released, never having been charged or offered a public apology for false imprisonment and torture. Within the military court, which keeps changing personnel, the trials basically start over with these terms again and again." Many of the contextual quotes in this article are by U.S. officials, but as Ginsburg humbly states, "We have learned and continue to learn about how to 'unlearn' the language we are given by the US government. We are working hard not to continue to perpetuate harm with language."

"The fact that the prison remains open twenty years later is because of U.S. partisan politics and, unfortunately, the prisoners there are hostages to that politics," said Ramzi Kassem, a professor at the City University of New York School of Law.[4] While Guantánamo seems to have largely fallen off the public radar, the political posturing at the recent Supreme Court confirmation hearing of Ketanji Brown Jackson exposed the still conflicted arguments. "The same Republican senators who are signaling concern about Jackson's work as a public defender, on behalf of Guantánamo Bay detainees, largely support keeping Guantánamo Bay open." Nevertheless, it is clear that the U.S. political process to release prisoners of war remains stalled after twenty years.[5]

"SOMETIMES YOU JUST CANNOT WAIT FOR THE U.S. GOVERNMENT TO DO THE RIGHT THING" – Aaron Hughes and Amber Ginsburg

"SOMETIMES YOU JUST CANNOT WAIT FOR THE U.S. GOVERNMENT TO DO THE RIGHT THING" – Aaron Hughes and Amber Ginsburg

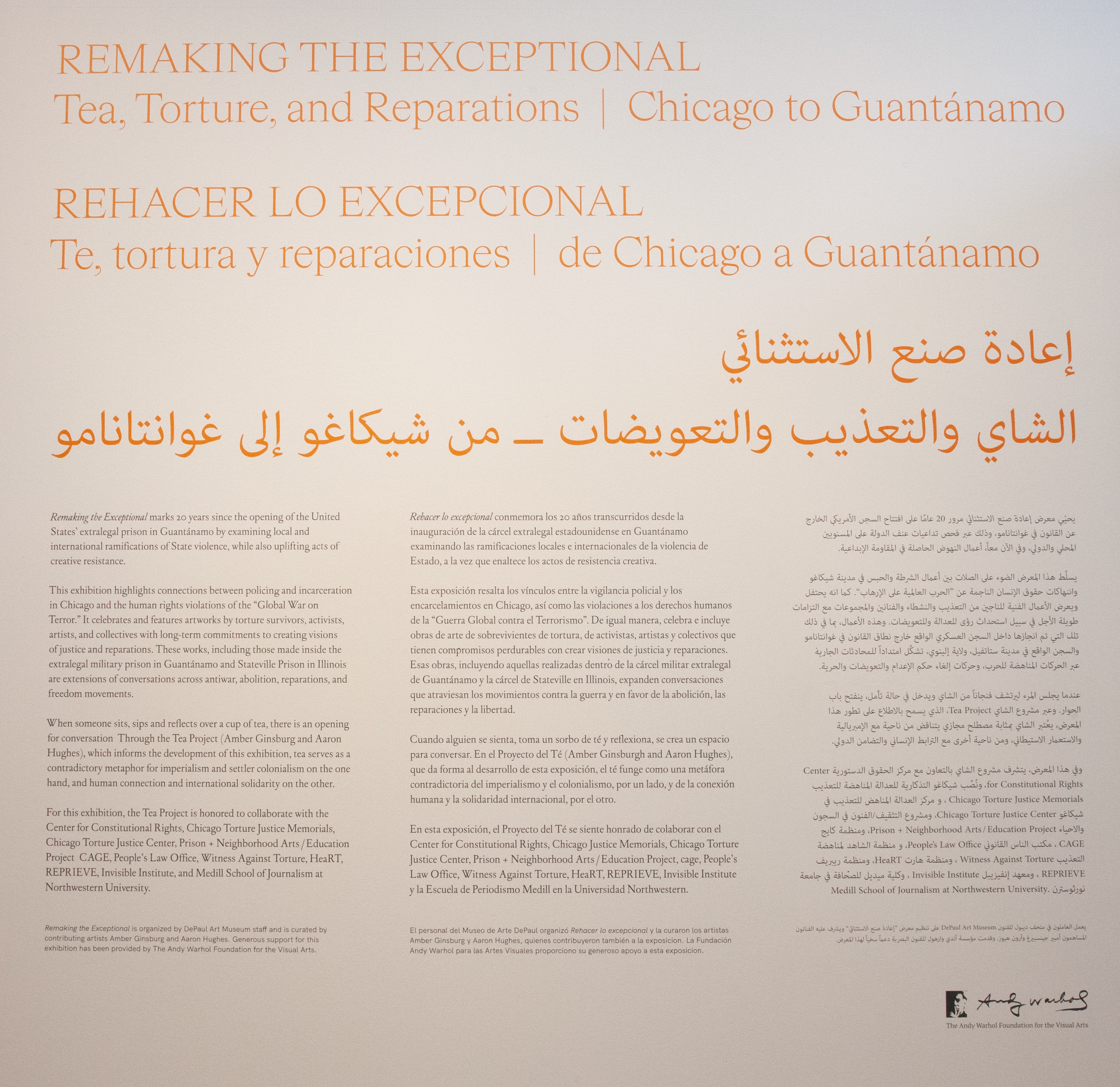

In a climate rife with political fractures and hidden bureaucratic stagnation, the artists Hughes and Ginsburg imagine reparations. Their multi-tiered mission includes the Tea Project, a podcast called Remaking the Exceptional, 780 cast-porcelain Styrofoam teacups, an exhibition at the DePaul Art Museum, and a fund for Guantánamo torture survivors. Through this project, they work to educate, advocate, and secure reparations for Guantánamo survivors. Given the magnitude of torture, the U.S. political backlog, and the sheer scope of Hughes and Ginsburg's project, there is a lot to unpack here. The following is a summation of the multifaceted efforts to provide solidarity, and awareness, and to protest nonviolently.

The Tea Project

"Iraq War veteran Aaron Hughes originally developed the Tea Project after a return trip to Iraq, as a civilian, in 2009."[6] He received tea prepared in the Iraqi tradition for the first time during his return trip. This authentic and subtle exchange stayed with Hughes, and upon his return to the U.S., Hughes developed the "social practice” art piece titled the Tea Project.

Since the mid-1990s, art critics and historians have worked to document the lineage and development of this amorphous set of social art practices. The genre has been identified under an ever-changing collection of brands, including new genre public art, socially engaged practice, relational art, dialogical aesthetics, and so on. Since 2008, however, the term "social practice art" has rapidly become professionalized through the emergence of conferences such as "Intervene! Interrupt! Rethinking Art as Social Practice" and "Open Engagement," as well as MFA programs offering tracks in social practice, such as California College of Arts, Otis College of Art, and Portland State University. While the product of social practice art is translated using a variety of disciplines (art, activism, journalism, anthropology, and community outreach) and can be seen as performance, activism, or material-based, the bottom line is that social practice maintains the idea of approaching a problem, rather than representing or exposing it.

First and foremost, the Tea Project needs to be understood as a process of communicative exchange rather than the exchange of commodities. Hughes works to construct bridges of communication between the worlds of intimacy, activism, sociology, and, most importantly, between art and humanity. When staged in a gallery space, the Tea Project reads like a performance piece that navigates discussions on war, detention, love, and tea. However, by offering the tea or conversations as a gift, in contrast to the monetary exchange of commodities as seen in a gallery space, Hughes humbly serves the emotional and innate needs of his recipients. The art exists in contribution to the audience.

First and foremost, the Tea Project needs to be understood as a process of communicative exchange rather than the exchange of commodities. Hughes works to construct bridges of communication between the worlds of intimacy, activism, sociology, and, most importantly, between art and humanity. When staged in a gallery space, the Tea Project reads like a performance piece that navigates discussions on war, detention, love, and tea. However, by offering the tea or conversations as a gift, in contrast to the monetary exchange of commodities as seen in a gallery space, Hughes humbly serves the emotional and innate needs of his recipients. The art exists in contribution to the audience.

Hughes' Tea Project creates a philosophical space – a space inherent to sipping tea – to reflect and "ask questions about one's relationship to the world: a world that's filled with dehumanization, war, and destruction; a world that's filled with moments of beauty, love, and humanity."[7] The Tea Project draws out participants' stories connected to living during the ongoing Global War on Terror. Hughes interlaces "stories of his deployment to Kuwait and Iraq in 2003, his return trip in 2009," and the "stories of his friend Chris Arendt, a Guantánamo detention camp guard, who fell in love with drawings carved by detainees into Styrofoam cups."[8]

780 Cast-Porcelain Styrofoam Teacups

/>In 2013, Hughes invited Ginsburg to join the Tea Project to cast 780 porcelain Styrofoam teacups, one for each individual held in extralegal detention since 2002. "Since then, Ginsburg and Hughes have worked collaboratively to expand the project and develop a multifaceted forum to engage with individuals' personal relationships to love, war, and extralegal detention."[9]

/>In 2013, Hughes invited Ginsburg to join the Tea Project to cast 780 porcelain Styrofoam teacups, one for each individual held in extralegal detention since 2002. "Since then, Ginsburg and Hughes have worked collaboratively to expand the project and develop a multifaceted forum to engage with individuals' personal relationships to love, war, and extralegal detention."[9]

Artists Hughes and Ginsburg were motivated by Arendt's account and others' stories of the detained men in the Guantánamo Bay detention camp drawing flowers on Styrofoam cups. The subtle and tiny acts of nonviolent resistance connected the isolated prisoners. In hindsight, the quiet acts of indenting flowers on Styrofoam cups united prisoners with a common message and helped reinforce a shared consciousness – I am still human; I still envision beauty in light of this torture.

While none of the original Styrofoam cups still exist, the artist Ginsburg creates "site-generated projects and social sculpture that insert historical scenarios into present-day situations."[10] Together Hughes and Ginsburg have masterfully captured the drawn indentions of flowers on Styrofoam for the cast-porcelain cups. Each cup bears the carved outline of a flower on each cup, which is repeated and represents an individual country. Consequently, the repeated flower corresponds to the number of men imprisoned in that specific country. For example, Afghanistan considers the tulip as its national flower; of the 780 cups, there are 220 cups with tulips, and each individual cup has 220 tulips on it to represent all of the 220 Afghan men imprisoned. There are forty-nine countries that have or have had a citizen detained at Guantánamo, and each is represented by a different flower.

While none of the original Styrofoam cups still exist, the artist Ginsburg creates "site-generated projects and social sculpture that insert historical scenarios into present-day situations."[10] Together Hughes and Ginsburg have masterfully captured the drawn indentions of flowers on Styrofoam for the cast-porcelain cups. Each cup bears the carved outline of a flower on each cup, which is repeated and represents an individual country. Consequently, the repeated flower corresponds to the number of men imprisoned in that specific country. For example, Afghanistan considers the tulip as its national flower; of the 780 cups, there are 220 cups with tulips, and each individual cup has 220 tulips on it to represent all of the 220 Afghan men imprisoned. There are forty-nine countries that have or have had a citizen detained at Guantánamo, and each is represented by a different flower.

Ginsburg's knowledge of cast-porcelain and background in craft perfectly parallel her interest in social and utopic histories that she translates as research-based multimedia installations. "During a 2014 Lawrence Arts Center Project-Based Artist in Residency, Hughes and Ginsburg, along with many incredible volunteers, opened a cup factory to produce the 780 porcelain Styrofoam cups."[11]

Podcast – Remaking the Exceptional

Since the manifestation of Hughes' original Tea Project, the 780 cast-porcelain Styrofoam cups, and the subsequent podcast have all grown progressively in scale. The podcast, Remaking the Exceptional, brings the voices of torture survivors and activists directly to listeners. Along with Nate Sandberg, the podcast producer and sound designer, Hughes and Ginsburg create seamless edits and transforming narratives, in that the voices of survivors take centerstage, shining a poignant and philosophical spotlight on the first-hand experience of being tortured. Remaking the Exceptional's podcasting model eschews the host Q&A standard and places the survivors in the role of audio guides. The podcast's momentum comes from the expansive connections between Guantánamo torture victims and policing practices in Chicago. While listening to the experience of torture and suffering is emotionally persuasive, the story becomes ever more significant, one interview at a time.

In episode two, Chicago Police Department detective and Navy Reserves Lt. Richard Zuley, who is accused of subjecting poor, Black, and brown Chicagoans to torture (from 1977 to 2007), is also connected to torture that he oversaw at Guantánamo from 2002 to 2004. The podcast further reveals that "under the direction of Chicago police commander and Vietnam veteran Jon Burge, police subjected hundreds of predominantly Black men and women to torture between 1972 and 1991."[12] The development of systematic torture of Chicagoans for thirty-seven years is then directly connected to the practices Zuley brought from his service in Chicago to his service at Guantánamo. Both Zuley and Burge have been the subject of torture investigations, but the podcast's parallel accounts of Chicago torture victims and Guantánamo torture victims are both objectively and psychologically striking.

"This system of oppression is connected internationally." – Kilroy Watkins, episode two, “Maps, Memory and Violence.”

"This system of oppression is connected internationally." – Kilroy Watkins, episode two, “Maps, Memory and Violence.”

At the heart of the podcast – and the predominant theme of the entirety of the multifaceted project – is the victim's response to being tortured and isolated. Former Guantánamo Bay detention camp guard Arendt, a friend of Hughes, gives a first-hand account of his experience: "One thing I miss is the cups. The detainees were only allowed to have Styrofoam cups, and they would write and draw all over them. I'm not totally familiar with Muslim culture, but I did learn that they don't draw the human form, and I'm not positive if they draw any creatures, but they draw a lot of flowers."[113] During the imprisoned men's mealtimes, they would be issued small Styrofoam cups, and while it was illegal, the men would scratch flowers onto the sides of the Styrofoam cups with their fingernails. Though the inmates would be berated for their creative acts of resistance, they continued to make these simple floral gestures. Arendt continues, "Then we would have to take them. It was a ridiculous process. We would take the cups—as if they were writing some kind of secret message that they were somehow going to throw into the ocean, that would get back to somebody—and send them to our military intelligence."[14] As heard in the podcast and in various news interviews, it's hard not to be sentimental about Arendt's reflections on the humble Styrofoam cups and the creativity and resilience of Guantánamo survivors call up strong emotion.

Fund for Guantánamo Torture Survivors

"A connection between torture in Chicago and torture in Guantánamo is not abstract, but direct," Ginsburg states. "In 2015, after years of activism by torture survivors, mothers, artists, educators, and attorneys, Chicago passed the first tangible reparations for racially motivated police violence in the United States."[15] Hughes and Ginsburg's multifaceted project aims to secure reparations for Guantánamo survivors similar to that secured by Chicago activists. The current reparations project and fund kicked off on March 10th, 2022, with the opening of Remaking the Exceptional: Tea, Torture, and Reparations – Chicago to Guantánamo, at the DePaul Art Museum. While ceramics is one of the many elements in the exhibition, works by Dorothy Burge, Debi Cornwall, and Abu Zubaydah are equally haunting and profound. Burge merges quilting and activism in her "quiltivism" portraiture creations of Black men who survived police torture in Chicago, and yet are still imprisioned. Cornwall's photographs of prisoners of war with their backs to the camera push the bounds of portraiture, and the hauntingly graphic courtroom drawings by Zubaydah – who was prevented from speaking in court but was allowed to draw his experiences of being tortured – are jolting and remarkable.

As they organize these projects for reparations, Hughes and Ginsburg set out to raise $100,000 from donations for 780 cups. "These funds will go directly to survivors to support their needs as they define them. In speaking with survivors, some of the needs they have identified include health care, housing and living expenses, training and education, and family support."[16]

What if value were placed not on objects but, instead, on investment in social restoration? Through discursive thinking, critical inquiry, and the functions of a cup, Hughes and Ginsburg have done just that. By using the cup as a moderator, the first and primary function of the 780 porcelain cups is to initiate social interaction, to reignite the dialogue between artist and viewer. It is clear Hughes and Ginsburg have a particular desire to create an active and engaged audience, one who will be empowered by the experience of physical or symbolic participation. Their work is more than "tea at high noon" – the art is fully committed to living in the realm of social contribution.

Hughes and Ginsburg's approach centers on democratizing strategic opportunities and engaging people in the subtleties and shared stories of social rebuilding. The tangible success is bringing these activist ideas and thoughtful issues to life in a collection of projects and mediums that brings together victims, survivors, and viewers in a space primed to address systemic challenges. Hughes, Ginsburg, and the participants in this project reach an understanding on the secrets of authentic and sustained engagement. Their multi-tiered project allows onlookers to see intricate connections to patterns of human behavior and avenues for social restoration.

Though Hughes and Ginsburg's work parallels many social practice themes, it is essential to remember that for them, this is not about reacting to social practice as a genre. Their work is about service and the human touch that makes a profound interpersonal difference. It is to restore the frayed relationship between artist and viewer, and make the relationship in service to one another. The cast-porcelain Styrofoam teacups are containers, vessels in a literal sense, but more importantly in an aesthetic and psychological sense. The space between torture and a gallery is fragile, but the foundation of human interaction (shaking hands, exchanging conversations and ideas over tea, and a closing embrace) strengthens this space. Hughes and Ginsburg remind all participants that the focus and interest in their work are not about making things but, instead, a focus on the life around the making of art and the subsequent healing that the victims of the War on Terror deserve. "The cups are a lasting collection of artifacts reflecting global conflict, while also being individual vessels that are easily lifted out of the display and into your hands for a cup of tea."[17]

Remaking the Exceptional: Tea, Torture, and Reparations – Chicago to Guantánamo is accompanied by a fully illustrated exhibition catalogue that brings together artworks, poetry, and testimony by torture survivors from Chicago and abroad, as well as new texts by leading scholars working at the intersection of aesthetics and politics. The exhibition will run March 10 through Aug. 7, 2022, at the DePaul Art Museum.

For a full list of Hughes and Ginsburg's multifaceted project head to the Tea Project.

For more on contributing, donating, and the Speculative Reparations Bill for Guantánamo Torture Survivors, head to "Imagining Reparations." Contributions for this fund are being accepted through the nonprofit Healing and Recovery after Trauma.

NOTES

[1] Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the International Committee of the Red Cross, the European Union and the Organization of American States (OAS).

[2] United Nations, “Rights Experts Condemn ‘Unrelenting Human Rights Violations’ at Guantánamo Bay,” January 10, 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/01/1109472.

[3] “The Guantánamo Docket,” The New York Times, March 11, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/guantanamo-bay-detainees.html.

[4] Roberts, William, “Why is Guantanamo Bay Prison Still Open Twenty Years After 9/11?” Al Jazeera, Sep 11, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/11/why-is-guantanamo-bay-prison-still-open-20-years-after-9.

[5] Carney, Jordain, "GOP Raises Red Flag on Supreme Court Nominee's Guantánamo Work," The Hill, March 14, 2022, https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/597938-gop-raises-red-flag-on-suprem...

[6] Tea Project, "Project History," accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.tea-project.org/tea-project#project.

[7] Tea Project, “Performances,” accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.tea-project.org/tea-project#performances.

[8] Tea Project, “Project History,” accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.tea-project.org/tea-project#project-history.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Tea Project, “Artist Biographies,” accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.tea-project.org/tea-project#artists-biographies.

[11] Tea Project, “Installations,” accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.tea-project.org/tea-project#installations.

[12] Remaking the Exceptional: Tea, Torture, and Reparations – Chicago to Guantánamo, DePaul Art Museum, accessed March 30th, 2022, https://resources.depaul.edu/art-museum/exhibitions/Pages/remaking-the-exceptional.aspx.

[13] Arendt, Christopher, "What It Feels Like... to be a Prison Guard at Guantánamo Bay," Esquire, July 30, 2008, https://www.esquire.com/lifestyle/a4821/guantanamo-guard-0808/.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Tea Project, “Fund for Guantánamo Torture Survivors,” accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.tea-project.org/new-index-2#fund-for-guantanamo-torture-survivors.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Tea Project, “Tea Project,” accessed March 30th, 2022, https://www.tea-project.org/tea-project#teacups.