No, I'm a Ceramic Artist

Today after work I veer from my normal routine and take a cab home instead of a bus to the subway, the subway to my bike, and my bike to my apartment. I am utterly exhausted after a week filled with first graders, a gallery installation, new-student interviews, and Chinese-language tutoring sessions. I greet the cab driver and tell him my address in Mandarin. He says okay and pulls into traffic. After a moment, he says, "You speak Chinese well." Knowing how to say my address and being able to tell the cab driver how to get to my apartment is one of the first things I learned to do in Taiwan. That, and how to order a coffee the way I like it. I reply, 'Thank you, but I don't think so; my Chinese is not good." He asks, "Are you a teacher?" I'm starting to think that mustering up all my new language skills and struggling through this opportunity to practice them is going to require more energy than the train, bus, and bike rides put together. Besides, I never quite know how to answer this question.

As a Western foreigner living in Taiwan, it is difficult to avoid being pegged as an English teacher. I would like this statement to suggest that I am not an English teacher and that on my Resident Work Visa my occupation is listed as "artist," but I'm obviously not making a valiant attempt to challenge anyone's assumptions by my wardrobe: a knee-length linen skirt, striped cotton tank top, button-down cardigan, ballet flats, watch, glasses, and a textbook-sized bag decorated with a pattern of berries and birds. For about twenty-five hours each week, I do, indeed, teach English to a bunch of privileged Taiwanese first- and second-graders. I use the word privileged in its exact definition; these students come from upper middle-class families who are paying private-school tuition rates. This is their after-school school, which prepares them for a test that will place them in the best middle school, then the best high school, then the best universities. Let's be honest: I am not a humanitarian. I am teaching English because it's a very well-paying job and because it matches the requirements of time and money needed to accommodate my "real" career. I've never not had another job besides being an artist, and this beats waiting tables in every way imaginable.

I teach an American-style curriculum, which is exactly what you are imagining if you think back on your own first-grade experience. The classroom has colorful bulletin boards littered with students' work, bookshelves full of books and supplies for science experiments and art projects, a computer connected to online learning videos and games, big windows, and each student's personal cubby. The kids learn math, language arts, science, and social studies. This sounds pretty normal, but these kids attend English school after having attended four or five hours of regular elementary school in the morning. Other ESL (English as a Second Language) curricula in Taiwan focus on grammar, with memorization and repetition as the mode of learning and with test scores as the only important gauge of the student's learning. I'm teaching in a special program in which experiments, activities, games, problem-solving, and critical thinking result in a completely different (and thoroughly American) way of learning through doing, not memorizing. My students are already equipped with better English and life skills than some university students I meet. This week's science lesson includes learning about matter: mass, properties, and chemical and physical changes of matter. What could be better to illustrate these things than clay?

This afternoon, after the students come in from their break, I tell them to clear off their desks, and there are little yelps of excitement because they know they'll do something besides read or write. I take out the bag of gray, solid matter and set it on the desk in the middle of the room. One student says, "Oh, teacher! I know this! This is... uh... teacher, I only know Chinese." Which means that he only knows the Mandarin word for clay. I say, "Nian fu ma?". The class erupts in echoes of "Aaaaahhhhhh! Teacher, you spoke Chinese!" Speaking Mandarin is strictly forbidden in this school, as a way of forcing the kids to use the English skills they've learned. So now I've broken the first commandment of Annie's English School, but nobody really cares because they are all giggling and excited to do whatever it is we are going to do with this clay stuff. As I cut some clay pieces and my hands get dirty, the next burst of sound comes from somewhere near a set of shiny black pigtails: "Aye-yuhF This is Mandarin for "Ew!" as in, "That's yucky!" Another girl asks, "Teacher, do we need to wear... that one thing... like this?" She holds up her hands and makes the motion of putting on gloves. "Oh, gloves?" I say, "No, it will just wash off; it's not bad for you." Meanwhile the pudgy boy with glasses (that he's actually wearing today rather than hiding under his desk) has gotten out of his seat and has his nose right up close to the clay, letting out another "Aye-yuhf".

At that, I have a crowd of ten students with their faces next to the bag, just begging to be affected by the scent, familiar to anybody who has ever worked at length with clay. The smell of raw, musty earth puts me in a really good mood; we are going to make something, and that is always fun. I let them get a whiff, and then tell them they'll all get their own piece, so go sit down. My other props for the lesson include a greenware bowl and a fired porcelain bowl that has a nice ting-ting song when I give it a little flick with my fingernail. We talk about the properties of the clay and the bowls and which ones have under- gone a chemical or physical change. They learn a host of new vocabulary, of which my favorite adjective is squishy. Everyone is totally game once they get ahold of the stuff, and they succeed to differing degrees at producing a small pinch pot. One of the students asks, Teacher, why can you do like that so good?" We are still working on grammar. I say, "You mean, why can I shape the bowl so well? Because I've been doing it for longer than you've been alive." Several little mouths with missing or over-sized teeth are gaping open, and then they start guessing, "Teacher, eight years?! Teacher, fifty years?! Teacher, one hundred?!?!" "Yes," I say, "one hundred years!" They double over in laughter knowing that they are being silly; one hundred of anything is just an insanely huge number if you're seven years old. It's also hard, if you are seven, to imagine that your teacher does anything else in the world besides teach you. So, as expected, they don't inquire more about my abilities as a ceramicist, but they will go home that day with a little token of a way, way cool English class.

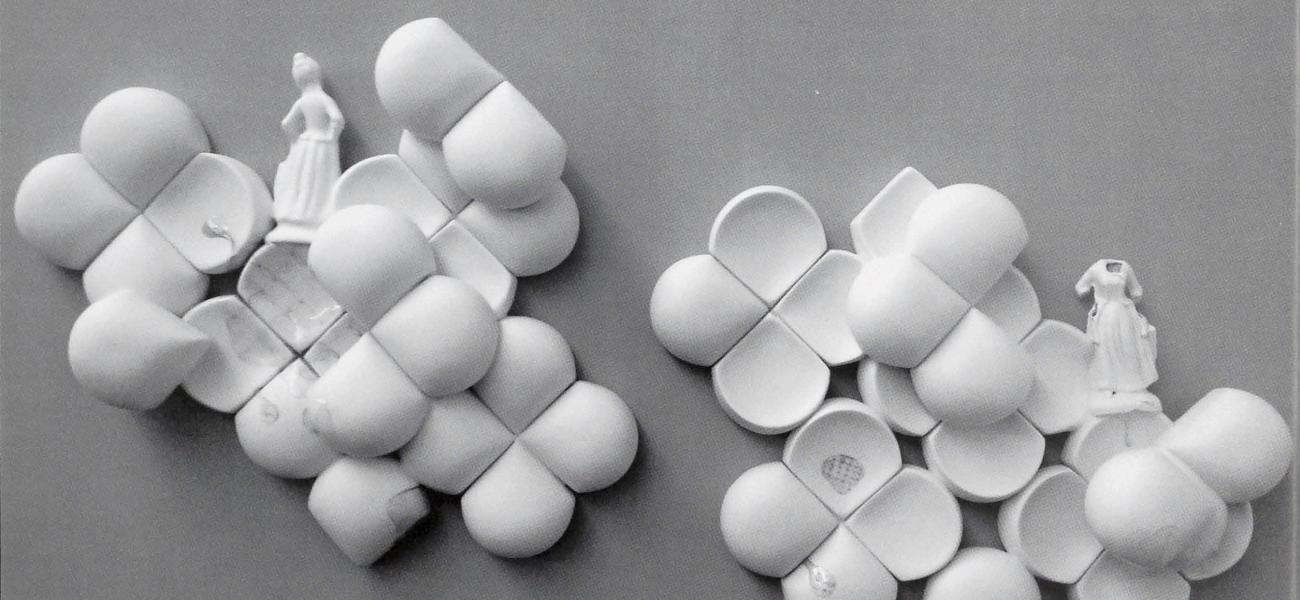

The timing for this little science lesson couldn't have been better. I send home, along with their small pinch pot, an announcement card for the current exhibition of my ceramic artwork. As I staple the cards into the students' "communication books," the mildly depressing thought crosses my mind that my little pinch pot, however amazing to my students, is the only thing I've made in clay this week, or maybe even this month. The thought vanishes with a sparkling "poof!" when I remind myself that I just installed my newest work in a group show of six Taiwanese ceramic artists and myself. And the fact that I was first-grader-free for the two days of installation cleared any remnant of somber smoke out of my head.

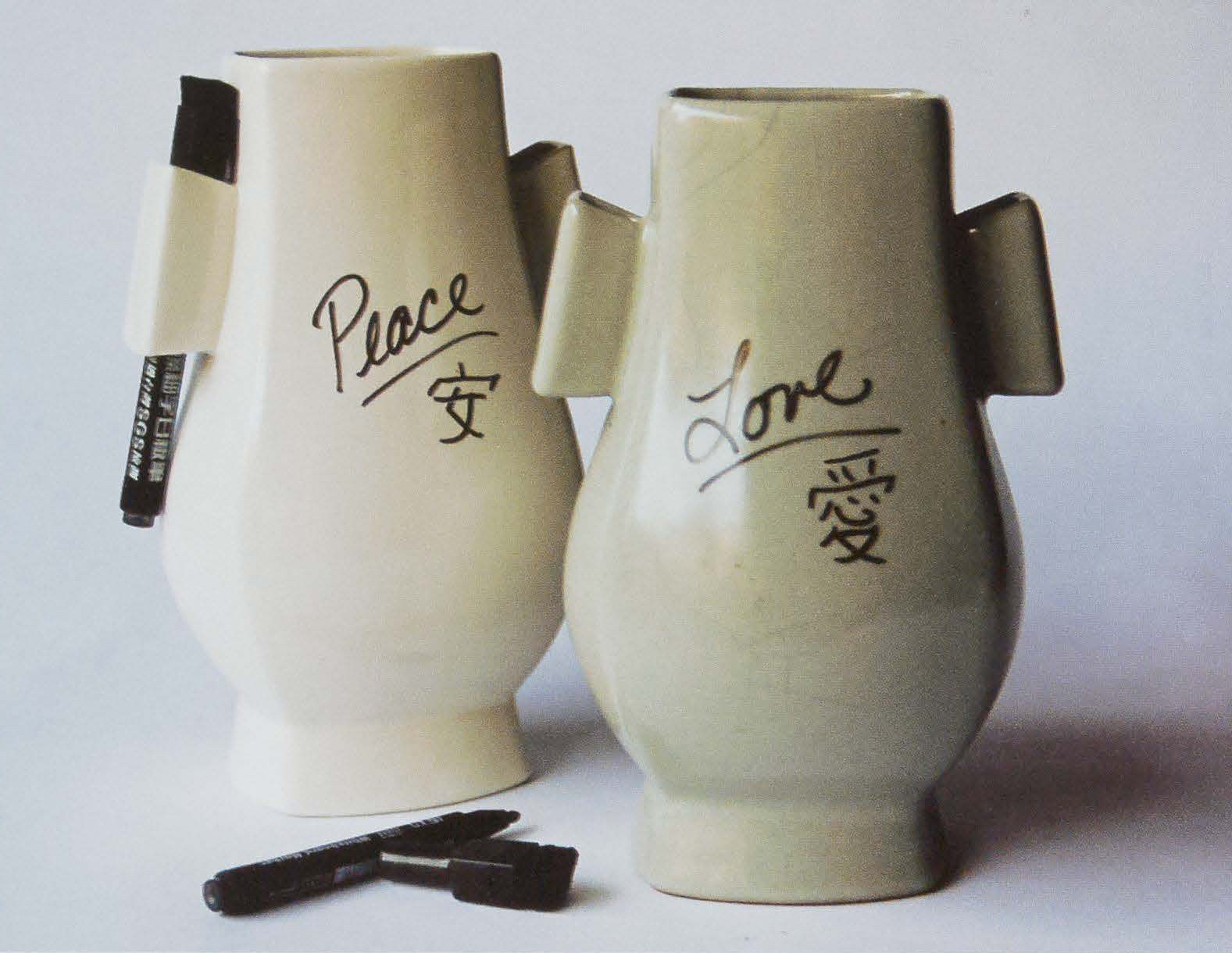

The organizer of the show is a small design company that supported my second studio residency in Taiwan. Having first come here as a resident artist, I was immersed in the community of ceramic artists and organizations that continue to support my work. So, although ninety percent or more of my income is made from teaching English, the jobs I've had here in Taiwan include studio artist, designer, workshop instructor, lecturer, children's ceramics teacher, art teacher, and docent seminar instructor for historic and contemporary ceramic art. Through this generous network of fellow artists, I've been able to spend about half of my time making artwork and the other half teaching in various ways. I would still rather be in the studio full time (who wouldn't?), but not a day goes by that I don't learn something about how to teach, how to leam, and how to better understand relationships between different people, different cultures, or different ideas. The opening for the show is postponed one week because of a couple of menacing typhoons headed our way, but I've already bought a sharp new slate-hued dress with a cinching belt and plunging neckline. I'd like to think that sporting this while striding around the gallery in a sexy pair of three-inch heels will bury any notion of "teacher"... at least until the following Monday. style="width: 600px; height: 464px; float: left;" title="Ears Vase, 2012. Stoneware, slip-cast 9.5 x 6 x 5 in. Based on an historic Guanware Chinese vase. Originally, the "ears" of the vase were meant for a carrying rope, but I replaced the rope with dry-erase markers introducing and interactive element to the " />

style="width: 600px; height: 464px; float: left;" title="Ears Vase, 2012. Stoneware, slip-cast 9.5 x 6 x 5 in. Based on an historic Guanware Chinese vase. Originally, the "ears" of the vase were meant for a carrying rope, but I replaced the rope with dry-erase markers introducing and interactive element to the " />

I decide to tell the cab driver, "Bush\ wo shi taociyishujia" (No, I'm a ceramic artist.) "An artist," he repeats, then asks, "Do you paint?" while making the motion of brush on canvas with his free hand. I know I'm proving that my Chinese isn't great. "No," I say," taoct (ceramics). He gives me a quizzical look in the rearview mirror."Nian iu," I say. "Oh!" he exclaims with too much enthusiasm, "Clay! That's good!" He then says something else from which I only under-stand a few words, but I can't piece together the meaning. I smile politely and tell him that I'm sorry I don't understand. We don't speak until we are near my street, and I tell him to make a right, then another right, and it's Lane 25. As I trudge up five flights of stairs to my fourteen-ping apartment, I check the time and see that I have a few hours before my head will start to bob. I can almost hear a game-show spinner racketing as my brain considers all the things I could get done: e-mail the studio about the catalogue, edit some part of my university-teaching application packet, write a blog post, upload pictures to Facebook for my family to see, pay bills online, read the next chapter in that James Elkins book, research the latest calls for entry... As soon as I walk in the door, the spinner lands on "sit on the couch with your boyfriend and watch one and a half episodes (because I won't make it through two) of something in the computer folder named television while consuming beer and steamed dumplings." I settle into the most comfortable couch in Taiwan and, in a tone that verges on complaining, tell my boyfriend, "We did a lesson with clay today in my class. The rest of the year is going to be so boring." He raises an eyebrow at me, and I know the meaning is, "You know that's not true." I smile a half-smile back that says, "I know that I know that's not true."

I can claim with certainty that teaching first graders a new language in a foreign country is on the other side of the universe from mundane; so is working in a design studio in a foreign country or merely taking a twenty-minute cab ride! I came here for a three-month residency, and I'm still here nearly three years later, not out of necessity but out of some addiction to the daily challenge of all things foreign and the reward of them becoming familiar as time passes. I'm looking forward to being surprised by how the experiences that have built the other 899 days like today will take shape in the future. That they will appear, be it under layers of glaze, as ink on paper, or in the sound of a familiar voice, is inevitable... and rather comforting.

Wan an!

Good night.