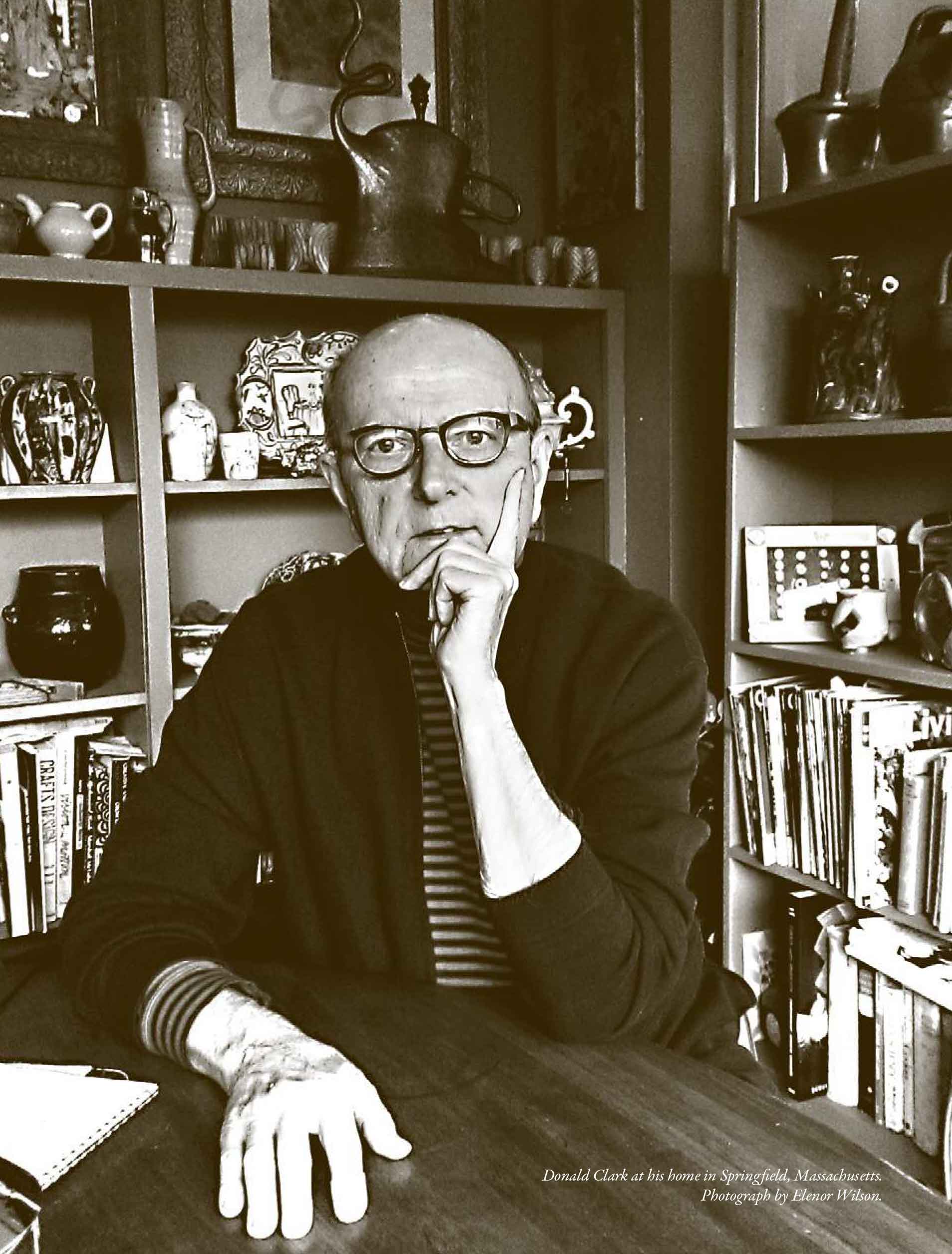

The following is the edited version of a conversation between SP editor, Elenor Wilson, and The Marks Project manager, Donald Clark, at Donald’s home in Springfield, Massachusetts, on April 8, 2015.

Elenor Wilson: For the record, will you state who you are and a little bit about how you came to be doing what you do now?

Donald Clark: My name is Donald Clark, and my primary occupation now is project manager for The Marks Project, Inc. I got to this place after having spent twenty-five years working in a gallery with Leslie Ferrin and meeting clay people from all over the country. My background was important to the development of The Marks Project: my being able to contact people and say, “Hey, it’s Donald. Guess what we’re doing now.” My résumé was having spent all those years in the clay world as a gallery person and then as a collector of hundreds of pieces of clay.

Donald Clark: My name is Donald Clark, and my primary occupation now is project manager for The Marks Project, Inc. I got to this place after having spent twenty-five years working in a gallery with Leslie Ferrin and meeting clay people from all over the country. My background was important to the development of The Marks Project: my being able to contact people and say, “Hey, it’s Donald. Guess what we’re doing now.” My résumé was having spent all those years in the clay world as a gallery person and then as a collector of hundreds of pieces of clay.

EW: What is The Marks Project (TMP)?

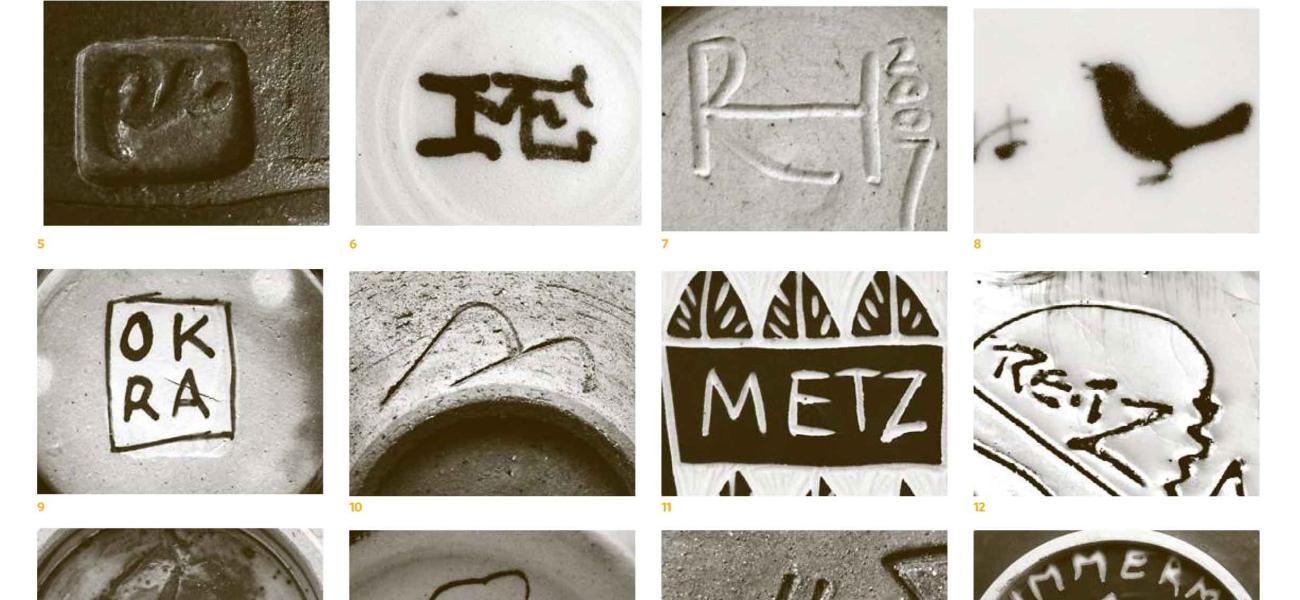

DC: TMP is a searchable online database of the marks, signatures, slashes, hashes, or whatever is used by a clay worker to identify his or her work. Martha Vida, the founding director, was very clear from the outset that this would be an online venture. If you write a book, you can’t change it. We wanted the ability to add information to what already exists, as artists grow and their work changes and their marks change. We’ve already had artists come back and say, “I just got this award. Can you put it in?” or “I had a piece purchased by the Smithsonian. Here’s its image. Let’s put it in.” None of that can happen in printed material. We hope we’ll be able – and people after us will be able – to keep this growing.

EW: What was the spark for the project – the first “Aha!” moment, the idea, or the conversation that started it?