Marinobel Smith and the Pan-American Ceramic National

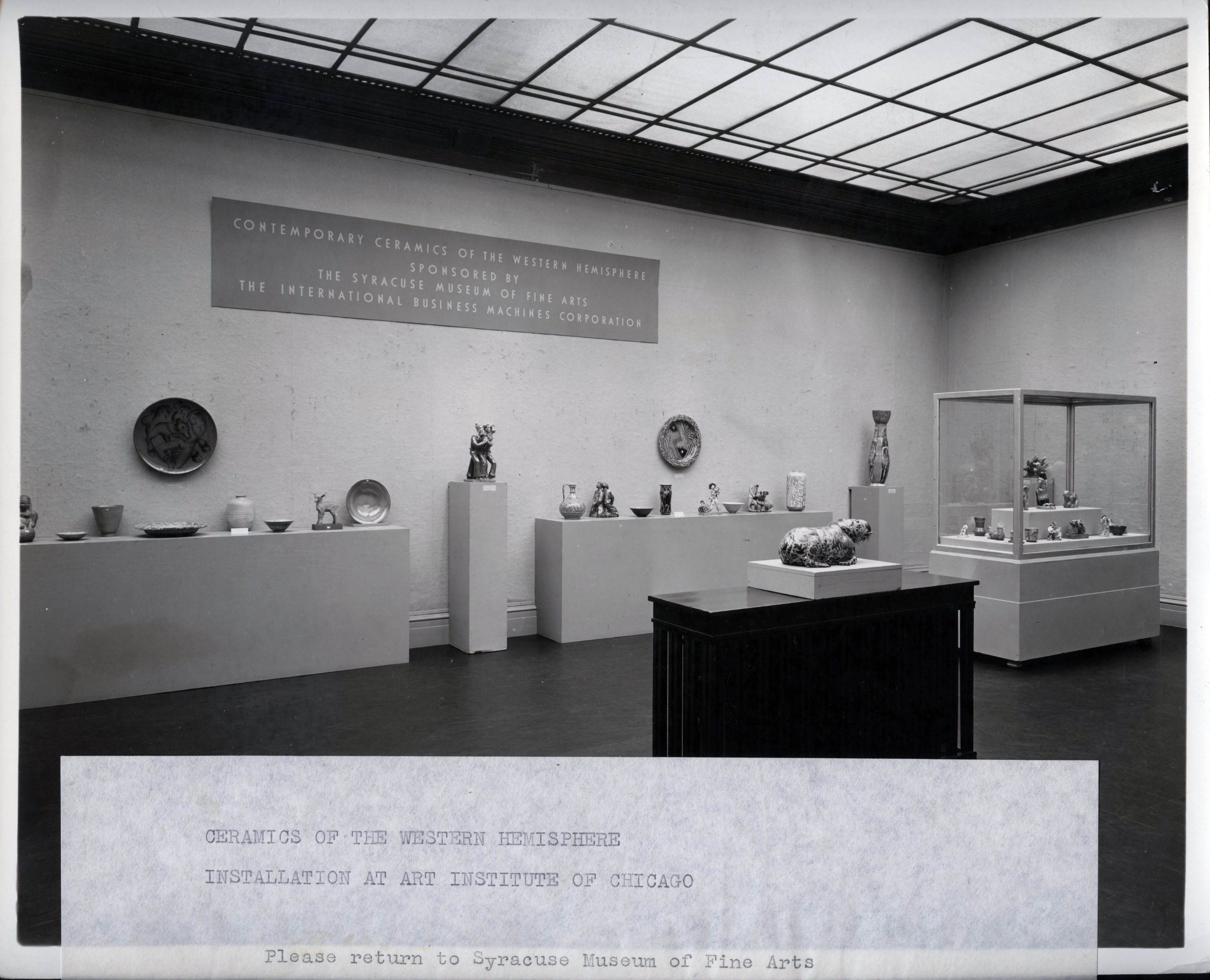

October 17th, 1941: the Tenth Ceramic National and Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere exhibitions opened for preview at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Art (now the Everson Museum of Art). The building was crowded with 541 objects surrounded by leaders of museums, corporations, and the mid-century craft field. Restrained white-wall galleries hosted settings for most ceramics, while others were presented in novel exhibition environments. On the main floor, “The Living Kitchen” from the New York World’s Fair was outfitted with industrial ceramics. Upstairs, utilitarian and sculptural works furnished an installation titled “Traditional Versus Modern,” where an old-fashioned dining room contrasted a contemporary living room.

October 17th, 1941: the Tenth Ceramic National and Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere exhibitions opened for preview at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Art (now the Everson Museum of Art). The building was crowded with 541 objects surrounded by leaders of museums, corporations, and the mid-century craft field. Restrained white-wall galleries hosted settings for most ceramics, while others were presented in novel exhibition environments. On the main floor, “The Living Kitchen” from the New York World’s Fair was outfitted with industrial ceramics. Upstairs, utilitarian and sculptural works furnished an installation titled “Traditional Versus Modern,” where an old-fashioned dining room contrasted a contemporary living room.

This was a far cry from the museum’s first Ceramic National, where American ceramics were exhibited on funerary casket crates – a clever adaption that was made due to the meager budget of the first event. Another difference: at this exhibition, the term “American ceramics,” described the international quality of the event. In assembly were contemporary ceramics from the United States, Canada, Iceland, and fifteen countries of Latin America: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

This was the largest exhibition of the medium at the time, the first Pan-American survey of contemporary ceramics, and it remains one of few US exhibitions that tried to characterize the varied approaches of Latin American ceramists. With seventy pieces of modern ceramics from the region, organizers assembled impressive examples made by leading artists; to name only a few, these included Marina Nuñez del Prado, the internationally acclaimed modernist sculptor from Bolivia; Diana Chiari de Gruber, who founded the National Pottery School in La Arena, Panama; the Paraguayan ceramist Campos Cervera who signed his work under the pseudonym Julián de la Herrería, and his wife, the Spanish-born Paraguayan artist and cultural influencer Josefina Plá. How did this all come together?

What follows is a layered story about Latin America’s influence on US studio ceramics before the post-war era.[1] It describes the impact of the Good Neighbor foreign policy on unlikely collaborators – a museum director, a businessman, and an influential yet understudied curator, Marinobel Smith, who traveled throughout the Americas (accompanied only by her sister) to collect contemporary art and craft for a tech giant. Last but never least, it’s about the makers and their ceramics – how their works were presented in the United States and influential inside and outside their contexts.

The impact of WWII on ceramic history has been well studied, but we often overlook the Good Neighbor Policy years before it. Introduced in 1933 during the inaugural address of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the “Good Neighbor” policy was created to improve relations with Latin America by building economic, political, and cultural interchange while renouncing interventionism in the region. As tensions grew in Europe, so did efforts to cement hemispheric solidarity through cinema, music, radio, theatre, and visual arts programs at home and abroad. Soon, Pan-American cultural events – funded by the newly established Office of the Coordination of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA) or influenced by their numerous projects – brought arts from Latin America to all types of public venues, including post offices, department stores, and museums.[3]

In the fall of 1941, the influential director of the Syracuse Museum of Art, Anna Wetherill Olmsted, organized a joint exhibition – the Tenth Ceramic National and the Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere exhibitions with the corporate sponsorship of the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). The collaboration between Olmsted and IBM founder and president, Thomas J. Watson, Sr., may seem surprising, but in 1941, their concerns were sympathetic. Both leaders were important supporters of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his federal art programs. Olmsted worked on various New Deal projects during her directorship, and in 1937, she was a Roosevelt-appointed delegate to the International Exposition in Paris.[4] Also appointed by FDR was Watson, the Commissioner General of the American Section of the fair. Inspired by this project, the IBM founder established the corporation’s Department of Fine Arts in 1938 to promote a “better understanding” between the “artist and businessman,” the “artist and his community,” and “people of different lands (between the Americas especially).”[5] Noticing the call for hemispheric solidarity, Watson and Olmsted looked to Latin America to support the government and, less idealistically, to enhance the reputations of their institutions.[6]

In the fall of 1941, the influential director of the Syracuse Museum of Art, Anna Wetherill Olmsted, organized a joint exhibition – the Tenth Ceramic National and the Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere exhibitions with the corporate sponsorship of the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM). The collaboration between Olmsted and IBM founder and president, Thomas J. Watson, Sr., may seem surprising, but in 1941, their concerns were sympathetic. Both leaders were important supporters of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his federal art programs. Olmsted worked on various New Deal projects during her directorship, and in 1937, she was a Roosevelt-appointed delegate to the International Exposition in Paris.[4] Also appointed by FDR was Watson, the Commissioner General of the American Section of the fair. Inspired by this project, the IBM founder established the corporation’s Department of Fine Arts in 1938 to promote a “better understanding” between the “artist and businessman,” the “artist and his community,” and “people of different lands (between the Americas especially).”[5] Noticing the call for hemispheric solidarity, Watson and Olmsted looked to Latin America to support the government and, less idealistically, to enhance the reputations of their institutions.[6]

Established in 1932 by Olmsted, the Ceramic Nationals were the first of their kind; they were juried competitions for United States ceramists that resulted in influential exhibitions. The events quickly grew through the years, traveling to museums and cultural centers nationally and internationally. At their height, they represented the status of US studio and industrial ceramics. When the textile designer Dorothy Liebes organized ceramic displays for the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939 in her position as the fair’s director of decorative arts, a selection of works from the seventh Ceramic National represented US ceramics at the fair. With the milestone of a tenth event, the upcoming national was a significant opportunity. To Olmsted, adding a Latin American section to the tenth National would bolster the prestige of the series.

As the director planned this ambitious event, she hoped to find two things: a prominent museum in New York City to host the national and a sponsor to offset its unprecedented costs. To encourage interest in the anniversary exhibition, Olmsted marketed the potential of a Latin American program and reminded her peers of the Nationals’ continued success. In one letter to the secretary of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Julian Street, Olmsted tried to enlist his support in approaching Nelson Rockefeller for funding. Previously, Rockefeller was the president of MoMA, and he was now the newly appointed leader of the OCIAA.[7] To host the exhibitions, she contacted the director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), Francis Henry Taylor, who was a supporter of the nationals and, like many, had made collection purchases through the national events. Reminding Taylor that her institution was “not a small museum seeking favors,” Olmsted explained that if The Met hosted the exhibition, it “would be the final, crowning seal of success” for the programs, “for although people come from all parts of the United States to see the exhibition in Syracuse, we do not, of course, draw the metropolitan audience that is possible in New York.”[8]

Ultimately, the OCIAA did not fund the exhibition and The Met did not host it, but Olmsted found a corporate sponsor in IBM. Perhaps more important, she found a curatorial collaborator – the art consultant (and soon-to-be director of the IBM Department of Fine Art), Marinobel Smith.

As one of few women in the field and in a leadership role at IBM, Marinobel Smith built a consequential art collection for a tech giant. Through its management, she made a lasting impact on US and Latin American relations, international art histories, and the permanent collections of prominent museums. In her personal life, she was an optimist and faith-filled person – especially during her later life in New Mexico, as she committed her efforts to the local community and the Baháʼí Faith.

As one of few women in the field and in a leadership role at IBM, Marinobel Smith built a consequential art collection for a tech giant. Through its management, she made a lasting impact on US and Latin American relations, international art histories, and the permanent collections of prominent museums. In her personal life, she was an optimist and faith-filled person – especially during her later life in New Mexico, as she committed her efforts to the local community and the Baháʼí Faith.

From the start, Smith seems to have merged her personal and professional life, finding satisfaction in pursuing her curiosities and sharing her findings with the public. In 1895, Smith was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and in 1915 she graduated high school in Brooklyn, New York.[9] Shortly after, she became a journalist at a local

paper. As an active suffragette and one of few women in journalism, she covered difficult stories and even found herself in the news – while at the Brooklyn Eagle, she “got the scoop” on a local murder case, and in 1920, various news outlets reported Smith’s efforts to return a kidnapped baby to his mother in Canada.[10] Three years later, Smith started her curatorial career for the Woodstock Arts Association – a Hudson Valley arts cooperative responsible for organizing exhibitions that gave “free and equal expression to the ‘Conservative’ and ‘Radical’ elements” of the Art Colony of Woodstock.[11] There, Smith met her future husband, the painter, sculptor, and fellow colony member, Warren Wheelock. They married in Kingston, New York, in 1924 (though her official name became Marinobel Smith Wheelock, she continued to use her birth name in her professional life).[12] Another example of her work ethic and progressive lifestyle: in the 1930 census and at the height of the depression, Smith reported that the couple was renting an apartment in Manhattan, her occupation was a freelance writer, and she was the “Head of House.”[13]

In 1938, she began her career at IBM as an art consultant for their new Department of Fine Art, and within three years, she was made its director. She assembled the company’s first collection and directed its subsequent exhibition: 79 Paintings from 79 Countries – a survey of contemporary art organized for the corporation’s pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.[14] In concert with the cultural diplomacy of the Good Neighbor policy, Smith built an influential collection of international art with a strong selection of paintings, prints, sculptures, crafts, and costumes from Latin America.[15]

To build a collection of this caliber, Smith regularly traveled throughout the Americas to build relationships with local authorities, museum directors, and art leaders who chose works to be exhibited (and often acquired) by the corporation. For Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere, she and her sister and secretary, Helen, took a steamship to Brazil and traveled for three months with an aim to purchase three to ten works from each Latin American country.[16] Though they were unable to reach their goal, the exhibition opened with ninety-three pieces of ceramics from fifteen countries in the region.[17]

To build a collection of this caliber, Smith regularly traveled throughout the Americas to build relationships with local authorities, museum directors, and art leaders who chose works to be exhibited (and often acquired) by the corporation. For Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere, she and her sister and secretary, Helen, took a steamship to Brazil and traveled for three months with an aim to purchase three to ten works from each Latin American country.[16] Though they were unable to reach their goal, the exhibition opened with ninety-three pieces of ceramics from fifteen countries in the region.[17]

The exhibition’s catalog suggests a degree of confusion about how to introduce the Pan-American theme of the Tenth Ceramic National and its unprecedented section of Latin American ceramics. In the introduction, The Met’s Industrial Arts Curator, Richard F. Bach, wrote a sprawling description of how a “ceramic Darwin” might analyze the exhibition’s design qualities through a “survival of the fittest” competition. Describing the state of the medium in Latin America, Marinobel Smith described her quest through “strange places and remote times” and explained that the region’s ceramists were animated by “a distinctly American spirit” that grew from a shared heritage of ancient civilizations. In the same text, Smith challenged her generalizations with numerous exceptions, describing various approaches to the medium and the influences of contemporary commerce, art academies, and industrial schools. Still, she concluded that “contemporary expression is in its infancy,” with “centuries separating the superlative work of the ancients from the output of contemporary potters.” With a competitive tone and a general description of Latin American ceramics, differences between regions were accentuated at the SMFA, as US, Canadian, and Latin American sections were placed in separate galleries. But this was only one way to organize the exhibition.

Pictured prominently at both the SMFA and the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) was a large plate by the Peruvian artist, socialist, and essayist Carmen Saco (1881-1948). During the artist's early career and education, the Peruvian government was actively investing in new social and cultural programs – one of which was a presidential grant that funded her first study trip to Europe in 1925. At the time, many Latin American artists traveled to European art centers to inform their own innovations. For Saco, this meant learning ceramic processes in Manises, Spain, partaking in the mainstream art world of Paris, and reporting her experiences in the Soviet Union to the Peruvian avant-garde publication Amauta. Saco challenged European influence and the exploitation of Native Peruvians through her artwork which often depicted pre-Columbian Andean motifs and contemporary Indigenous cultures. In a 1928 issue of Amauta, the art critic Ricardo Florez said of Saco, “[she] doesn’t pretend to please the Londoners or the Parisians.”[19] Perhaps she did not care to please the New Yorkers or the Chicagoans, either.

Though highlighted at both institutions, Saco’s work took on contrasting associations when re-installed. In an image taken at the Syracuse preview, the Plate is seen on a pedestal as Thomas J. Watson, Sr. reaches for a Moche period figural vessel in a room dedicated to the Latin American section. Though the exhibition’s title included the term “contemporary,” about twenty-five percent of the Latin American section was made of historic works.[20] Yet, when the AIC installed the entire Tenth Ceramic National and the Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere, all contemporary sections were exhibited together, but historic ceramics – described as “colonial period” works from Ecuador, “archaeological ceramics” from Mexico, and “ancient ceramics” from Peru – were not pictured next to the modern ceramics. Under the exhibition’s title on the gallery wall, Saco’s Plate with two fish hangs parallel to Rodeo Plate by the US artist Don Schreckengost.

Though highlighted at both institutions, Saco’s work took on contrasting associations when re-installed. In an image taken at the Syracuse preview, the Plate is seen on a pedestal as Thomas J. Watson, Sr. reaches for a Moche period figural vessel in a room dedicated to the Latin American section. Though the exhibition’s title included the term “contemporary,” about twenty-five percent of the Latin American section was made of historic works.[20] Yet, when the AIC installed the entire Tenth Ceramic National and the Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere, all contemporary sections were exhibited together, but historic ceramics – described as “colonial period” works from Ecuador, “archaeological ceramics” from Mexico, and “ancient ceramics” from Peru – were not pictured next to the modern ceramics. Under the exhibition’s title on the gallery wall, Saco’s Plate with two fish hangs parallel to Rodeo Plate by the US artist Don Schreckengost.

Though made by a Latin American ceramist, Saco’s plate was potted and fired in Europe; Manises, Spain, to be exact. On its reverse, the earthenware-looking dish reveals more information: it is made of white clay, and a hand-written note describes its decoration as being in an “ancient Peruvian cultural style.” Instead of leaving the light clay body visible, Saco decided to cover the work with a reddish-brown glaze, and she accentuated the animal forms with thick contour lines in black. Stylistically, these decisions refer to the earthenware ceramics of the ancient Nazca civilization, while also marking Saco’s participation in a contemporary art movement.

In Paris, the Peruvian textile designer, illustrator, and educator Elena Izcue was actively advocating for the use of ancient Andean motifs in the national arts of Peru and international Art Deco. First studying pre-Columbian objects in Peru, Izcue moved to Paris, where she authored and illustrated El Arte Peruano en la Escuela (1926) – an educational arts workbook that offered pre-Columbian history and motif drawing exercises for Peruvian students. From 1928 to 1938, Izcue ran a successful textile studio and successfully collaborated with fashion designers and retailers in Paris and New York. Between her educational textbooks and internationally celebrated textiles, Izcue was a substantial force in popularizing pre-Columbian motifs throughout the 20s and 30s. Curiously, the fish on Saco’s Nazca-inspired plate is also found in two of Izcue’s fabric designs.[21] Though the SMFA positioned the ceramist’s artwork as local, stagnant, and historic, it was actually an active part of an international and cosmopolitan trend.

Like Saco, Don Schreckengost was inspired by recent travels. In 1939, he was a professor in the Ceramic Art Department of Alfred University and accepted a summer position in Guanajuato, Mexico, at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in San Miguel de Allende (now the Centro Cultural Ignacio Ramírez “El Nigromante”). During this time, he worked on at least one mural for the school, perhaps in collaboration with the Mexican painter Pedro Martínez. Documentation reliably attributes murals to Martínez, but inconsistently describes Schreckengost’s involvement.

Despite these inconsistencies, Schreckengost’s decorated Rodeo Plate (1940) with a figure that looks uncannily similar to the central figure in El Fanatismo del Pueblo (1939) by Martínez. In the mural, a winged creature is attacking a group of fleeing women as two caballeros deftly lasso the beast. Made after the mural, the ceramic is decorated with a cowboy wrestling a bull. In both compositions, on a similar theme, the cowboy figures wear hats, boots, and nearly identical belts. With their face in profile, their cheekbone and jaw are similarly defined. Don Schreckengost may have been present as Martínez worked on El Fanatismo del Pueblo. More certain: his time in Guanajuato influenced the subject of Rodeo Plate. Perhaps none of these details were appreciated in 1942, but when the Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere sections were integrated in Chicago, it became a more accurate reflection of the idealism of cultural interchange, the state of international ceramic networks, and the diversity of studio ceramics.

Shortly after WWII’s end, the Good Neighbor Policy concluded as a new period of US interventions in Latin America developed with the Cold War. In 1946, Anna Wetherill Olmsted organized the 11th Ceramic National, and Marinobel Smith reported that the IBM art collection was recognized for containing one of the foremost collections of Latin American art. Smith and her husband relocated to New Mexico in 1949, and soon after the IBM fine art division was reorganized as the “Department of Arts and Sciences.”

Still, Smith and Thomas J. Watson Sr. maintained cordial correspondence through letters. In one dated June 1954, she updates him on an inexplicable tragedy. “I am not walking,” “the trouble is my stubborn knees don’t listen to me nor to reason.” She jokes to Watson, Sr., “How ironic that anyone with my knee history should have entered a plunging elevator! There’s something almost epic in such a combination.” Ever optimistic, Smith said, “I could start blaming the stars for what has befallen me, Mr. Watson, if it weren’t for the exciting challenge of the odds against me…”[22]

Until her death on August 20, 1968, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Marinobel Smith remained active despite her injuries. She pursued writing projects, volunteer work, and travel – even visiting Guadalajara, Mexico, in the last months of her life. Throughout the 1960s, IBM gifted much of its collections to institutions throughout the United States.[23] Today, many of Marinobel Smith’s acquisitions rest in the storage facilities of influential museums, where they await new interpretations and, hopefully, another exhibition.

Endnotes

[1]Today, the impact of Latin America on US studio craft is more recognized in the post-war era, but many notable studio craftspeople traveled, worked, and studied in Latin America during the Good Neighbor years (1933-1946). To list only a few: The Austrian-American ceramicist Adolph Odorfer worked in Mexico and Brazil at ceramic studios and factories before settling in Fresno, California, in 1935. Don Schreckengost was a guest instructor at the Universitaria de Bellas Artes in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, in 1939. As WWII ended in 1945, Glen Lukens was sponsored by the Inter-American Educational Organization and the Haitian government to establish a ceramic studio in Haiti. In the same year, Mary and Edwin Schier, who would later settle in Mexico, were employed by the Puerto Rican government to establish a small ceramic industry. Soon this project was taken over by Hal Lasky, and the deeply carved sgraffito decoration remains synonymous with Puerto Rican pottery.

[2]Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere. (Syracuse: Syracuse Museum of Art, 1941), 6-8.

[3]Established in August of 1940, the OCIAA promoted hemispheric solidarity through international motion picture, theatre, radio, and visual art programs. Led by Nelson Rockefeller, the office funded and inspired cultural institutions to pursue Pan-American exhibitions and collection accessions of Latin American artworks.

[4]Cheryl Buckley “Subject of History? Anna Wetherill Olmsted and the Ceramic National Exhibitions in 1930s USA,” Art History vol 28, no. 4 (September 2005): 500.

[5]Marinobel Smith “Brief Summary, History and Development, IBM Department of Fine Arts” IBM Fine Arts Department, May 1946. IBM Corporate Archives

[6]Since 1917, IBM had offices in Latin America. IBM’s processing of statistical data was of interest to nations whose governments were updating economic, industrial, and social programs. By the end of WWII, the company had at least 19 offices in the region, a sales school in Santiago, Chile, and a technical school in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

[7] Anna Wetherill Olmsted to Julian Street, March 12, 1941, Ceramic National Exhibition Archive.

In her letter of March 12, 1941, to Julian Street, Anna Wetherill Olmsted pursues the “possibility of interesting Mr. Nelson Rockefeller in an interchange of ceramic art exhibitions between the United States and the South American countries.”

[8]Anna Wetherill Olmsted to Francis Henry Taylor, March 27, 1941, Ceramic National Exhibition Archive

[9]“Erasmus Hall Graduates 254” Brooklyn Times Union, June 25, 1915, 4.

[10]“Suffrage Activities” The Evening Journal, September 8, 1918, 7.

“Noted By-Line Gals Got Start on Eagle” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 22, 1936, 9.

“Stagg Extradition Fight Underway,” The Sunday Oregonian, Oct 24, 1920, 4.

[11]Brook, Alexander. “The Woodstock Whirl,” The Arts 3, no. 6 (June 1923): 420.

[12]Warren Wheelock reported that they married in 1925, but marriage records document that they were wed in 1924.

[13] Between 1925 and 1937, Smith remained busy as she submitted written contributions to publications and worked intermittently at various cultural institutions. In 1926, Smith worked as the executive secretary of the Executive Committee of Columbia University. In 1930, Smith was working as a manager of performances at the Westchester County Centre. At one point during these years, she was a director of publicity for Town Hall, Carnegie Hall.

[14]In 1949, Smith and Wheelock relocated to Santa Fe, New Mexico. There she found the Bahá'í Faith, and continued to work on contractual projects for IBM as her health declined. Marinobel Smith passed away at 72 years old in Santa Fe on August 22, 1968.

[15]Marinobel Smith “Brief Summary, History and Development, IBM Department of Fine Arts” IBM Fine Arts Department, May 1946. IBM Corporate Archives

In the document Marinobel Smith quotes Robert Smith, the director of the Hispanic Division at the Library of Congress, as he described the IBM Fine Art Collection as the “best collection of Latin American Art in the United States.” Marinobel Smith also reported that more than 12,000,000 people had seen “IBM art” as it “visited more than 350 museums, galleries, and universities of the Western Hemisphere.”

[16] Marinobel Smith to Anna Wetherill Olmsted, September 1, 1941, Ceramic National Exhibition Archive

In the letter Smith mentions she wants to acquire three to ten ceramics from “every one of the 20 Latin American countries.” Likely, Smith is referring to the twenty Latin American countries that were members of the Pan American Union.

[17]In Design a description of the exhibition states that more objects were added to the exhibition as it traveled to W. & J. Sloane Company in New York City and throughout the nation’s cultural institutions: the Chicago Art Institute, Corcoran Art Gallery, Cincinnati Museum, and the Philadelphia Art Alliance. “The First Exhibition of Contemporary Western Hemisphere Ceramics,” Design 43, no. 4 (December 1941): 6.

Despite this statement, exhibition catalogs were not adjusted to reflect these additions.

[18]Contemporary Ceramics of the Western Hemisphere. (Syracuse: Syracuse Museum of Art, 1941), 31-32.

[20]Unlike the US-American and Canadian sections that only included contemporary works, twenty-five percent of the Latin American section displayed historic ceramic.

[21]See Textile Design (ca.1928-1936) by Elena Izcue, Museo de Arte de Lima, Donation of Elba de Izcue Jordán, object 2015.15.1520. Another example is pictured in the online article https://feriadeartedelima.com/2020/07/20/el-legado-de-elena-izcue/

[22]Marinobel Smith to Thomas J. Watson, Sr., June 6, 1954, IBM Corporate Archives

[23]In the 1960s, IBM Corporation gifted a range of objects to art museums. This includes the El Paso Museum of Art, the Everson Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, North Carolina Museum of Art, and various museums of the Smithsonian Institution. In 1983, IBM opened a new gallery in New York City and described that the business did not have a permanent collection.