Innovation: A Matter of Connections

As a society and as individuals, we assume innovation is a necessary element in significant artistic expression. This assumption that the highest expectation for the artist is to introduce something new is a pervasive part of our nation's collective consciousness. As Americans we thrive on the idea of newness as a universal good; after all, we live in the New World. We presuppose that every artist's main goal is innovation and that newness is fashionable and marketable. Eventually, this assumption leads to the question: Is anything ever really new?

The art historian George Kubler seems to think not. In his book, The Shape of Time, he writes: "It is possibly true that the potentialities of form and meaning in human society have all been worked out at one time and place or another, in more or less complete projections."1 This statement implies that human beings would have to change dramatically before anything truly new could emerge from their actions. He goes on to state: "Perhaps all the fundamental technical, formal, and expressive combinations have already been marked out at one time or an- other, permitting a total diagram of the natural resources of art, like the models called color-solids which show all possible colors." He continues by saying that, were his hypothesis to be verified, it would radically change our concept of the history of art. "Instead of our occupying an expanding universe of forms, which is the contemporary artist's happy but premature assumption, we would be seen to inhabit a finite world of limited possibilities, still largely unexplored, yet still open to adventure and discovery, like the polar wastes long before their human settlement." These thoughts suggest that anything new is and must be the result of an exploration of limits. Certainly, rules or even casually assumed limitations have often been the only catalyst needed to set a creative mind in motion. By establishing a structure to question and investigate, limits provide a starting point for the artist.

A structure or framework of limitations is usually founded on past experience, which frequently convinces us of the impossibility of accomplishing something new. Therefore, assumptions about and perception of experience, either collectively or individually, play an important role in the process of invention.

The past, of course, gives the new its context; we cannot know what is new unless we know what is old. By implication, this statement suggests as a fundamental principle of artistic expression that no work or art contains its complete meaning in and of itself. Artists refer to the past to evaluate their work and infuse it with meaningful content. Philip Rawson writes in his book, Ceramics: 'The basis for expression in ceramics—as in the other arts—is the way the forms of a pot implicate in their presence a wide range of the spectator's personal experience."2 In other words, the expression or meaning in a work of art is dependent on references. Not only is past experience important to an artists development, but also his or her work must allude to the experience of the viewer. T. S. Eliot writes: The poem which is absolutely original is absolutely bad; it is, in the bad sense, 'subjective,' with no relation to the world to which it appeals."3

If it is true that no work of art contains its complete meaning without context or reference, then nothing is ever totally new. Even if it were possible to create something absolutely new, it would probably lack power, as T. S. Eliot points out, because it would be without meaning. In this sense, a frontal assault on innovation as an artistic tactic is as illusory as Ponce de Leon's quest for the Fountain of Youth, and the artist's motivation becomes mere ego.

Innovation in art is not a matter of new forms; it is a matter of new connections- new insights, new relationships, new thoughts-brought to bear on the timeless human condition. The creative process involves a search for the connections between the artists perception of outer reality and his or her inner feelings and sensations. These connections are triggered by an encounter with life and are meaningful to the degree that they bring, via the work of art, understanding or knowledge to the artist and to the viewing public. Rolla May, a well-known psychologist, writes in his book, The Courage to Create: "We cannot will to have insights. We cannot will creativity. But we can will to give ourselves to the encounter with intensity of dedication and commitment."4

Vincent Van Gogh's painting 'The Starry Night" in 1888 was not a radically new painting, but it brought forth new connections and gave new vision to those who took the time to experience its presence. Today it still has the power to change forever the way one sees the night. The power to change the way we see-to change our lives-is the element of significance in innovation, and thus the quality of the connections made by a work of art separates the importantly new from the merely different. The merely different is entertaining but ephemeral. The truly innovative is metaphoric and changes us forever.

An excellent example of creative work that carries out this pattern for innovation is the work of Joseph Cornell. Working in the terrain of the ordinary, Cornell made connections between things in such a way as to transform them into psychically charged sculptural statements. He convinced us that the common object could deliver a potent message precisely because it was not new but rather had a past, something to be remembered.

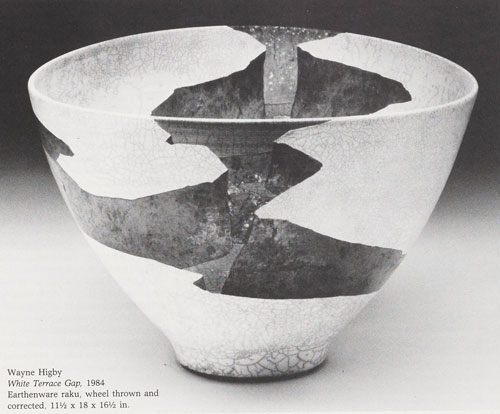

Memory plays an important role in the creation and appreciation of a work of art. In my own work it is the commonplace bowl that serves as the known point of departure, the starting point for chains of associated memory. As an artist, I am in pursuit of a connection or series of connections between my emotional attraction to ceramics and my responsiveness to landscape. I am searching for understanding and for some illusive form of truth that is difficult to articulate. This search results in the creation of ceramic pieces which serve as a testing ground or viewfinder for my perception. In that sense, the art object is the byproduct of a never-ending effort to reach a special level of insight.

Innovation itself has never been a direct concern of mine. The new qualities that I have brought to pottery and the raku process are the result of looking for a combination of form, imagery, color, surface, and fire that would give back to me a needed emotional resonance. To me it is important that my work be innovative, but I am more concerned with becoming part of a continuum that reaches backward thousands of years and yet has vitality in the present. Being a participant in the continuous evolution of pottery keeps me in touch with a timeless symbolic language that supports my own personal quest for essential meanings.

If it is possible to put trust and conviction into one's own relationships to the world, innovation will naturally occur. To try for self-confidence while demanding intense encounter is important. The rest depends on one's willingness to work it out. Igor Stravinsky writes: 'Invention presupposes imagination, but should not be confused with it. For the act of invention implies the necessity of a lucky find and of achieving full realization of this find. What we imagine does not, necessarily, take on a concrete form and may remain in a state of virtuality, whereas invention is not conceivable apart from its actual working out."5 In other words, innovation takes place in the context of working. Materials, in Stravinsky's case musical components, provide the matrix for a lucky find. While working, one must develop flexibility and call on experience to use what is found. An artist must be not only a participator in the creative art, but also an observer of his or her participation. Therefore developing a wide range of interests would augment the process of making connections and facilitate observation. The ability to bring several points of view to the creative act enhances the possibility of discovering the unexpected. Above all, in the effort to succeed, the artist must acquire the willingness to fail. Accepting anxiety and learning from dissatisfaction also helps keep oneself on the edge of the creative process where the current flows fast and the sparks fly. Innovation can and does occur out there on the edge. The sparks ignite ideas and light the way for invention.

Henry Varnum Poor wrote in his book, From Mud to Immortality: "I believe that the only essentially new thing in a work of art is the freshness of a new person and his fresh discovery of the world, of a spirit that expresses itself with confidence and freedom."6 To this I would add that any success an artist might have provides a new starting point. Everything accomplished is firm ground for another beginning. With this in mind, one can continually engage in self-discovery and the passion of inquiry. Past experience becomes a tool for opening new horizons. These give the artist a purpose and reason to exist and to continue working.

Footnotes:

1. Kubier, George, The Shape of Time. New

Haven and London: Yale University

Press, 1962.

2.

Rawson, Philip, Ceramics. Philadelphia:

University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.

3. T. S. Eliot, "Tradition and the Individual

Talent."

4. May, Rolla, The Courage to Create. New

York: W. W. Norton, 1975.

5. Quoted in Herbert Read, The Origins of

Art. New York: Horizon Press, 1965.

6. Poor, Henry Varnum, A Book of Pottery,

From Mud to Immortality. Englewood

Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1958.