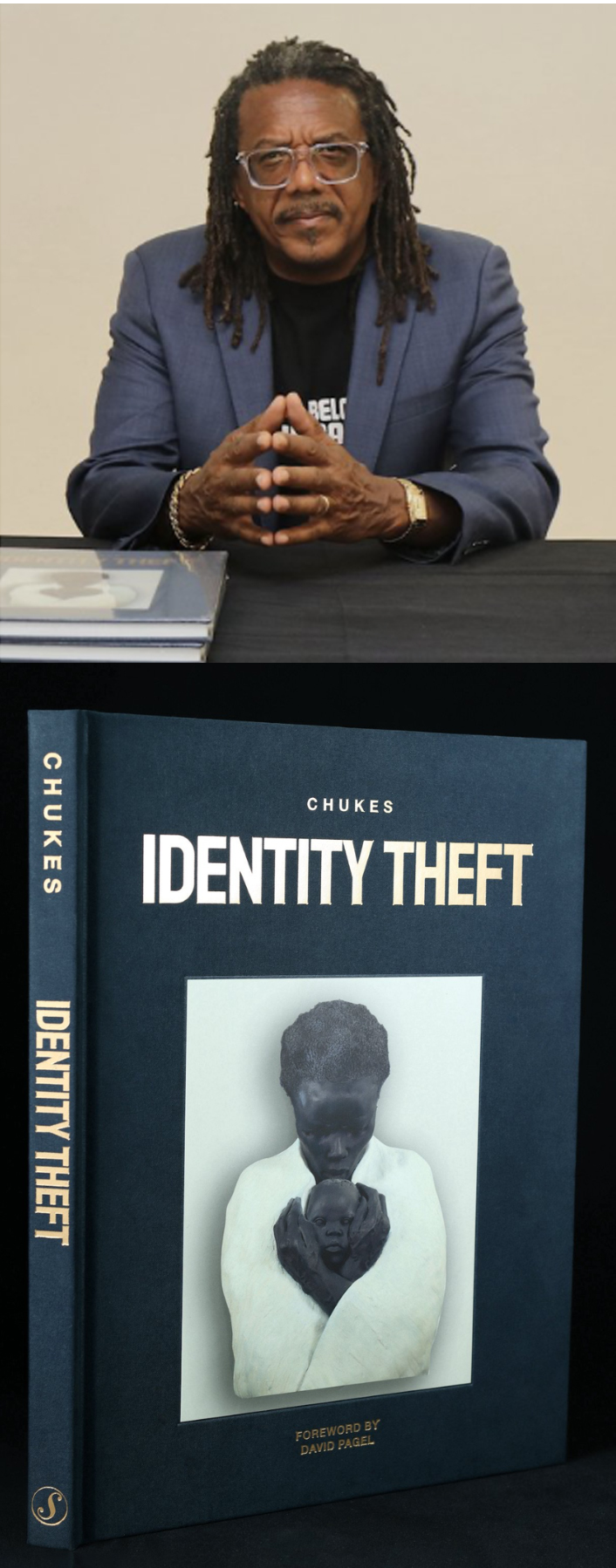

Identity Theft - Creations from a Social Conscience.

“I am one of the fortunate ones. Had I believed what I was being taught in school, I would never have known the true meaning and greatness of my last name, “Chukes.”

– Michael Chukes

We often hear that slavery was our country's original sin, but that’s not accurate. It has been 248 years since the founding of the United States, and this is our enduring shame, one that has wreaked suffering on no less than ten generations. Michael Chukes’s work is a barometer of this social consciousness, measuring, no, warning of the enduring build-up of pressure and pain.

Slavery is a hard history – a hard and meaningful conversation – but Chukes (as he prefers to be called) challenges ignorance, perception, and distraction in a quest for communal enlightenment. In his 2023 book Identity Theft - Creations from a Social Conscience, Chukes reflects on forgotten and untaught histories, asking his readers to “start asking questions about your history! Start by asking your elders, and don’t hold back.” Although his work captures the sensory knowledge of enduring suffering, David Pagel, Professor of Art Theory and History at the Claremont Graduate University, notes that it’s “not just pointing out the tragic, century-spanning losses of having one’s self stolen, but by repairing the damage, and then some.”