Hawaii, A Haole in King Kamehameha's Court

Web Editor’s note: This is the third of three sections in “Hawaii, A Haole in King Kamehameha's Court.” The first two are also by Gerry Williams, subtitled Oahu, and Maui. Members can read the digital issue online by logging into our site, and receive a significant discount on a PDF download of the entire issue. Non-members can purchase a downloadable PDF here; this issue is sold-out in print.

HAWAII

Chiu Leong strips off his shirt and steps briskly onto the black lava flow. The sun blazes down and its hot. I tie a handkerchief around my head and follow Chiu. We pick our way across a mile of crunchy a' a' and smooth pahoehoe lava toward our goal of a molten river of lava in the distance.

I had asked Chiu to take me to see the river of lava flowing from the flank of Kilauea, and we left in the morning to drive through the towns of Keaua and Pahoa on a road recently cut by engulfing lava. Soon we turned off the highway onto a forest track that angled for five miles through the underbrush and across the mountainside. We came to an abrupt stop when confronted by a giant foot of congealed pahoehoe lava smack down in the middle of the road. We were forced to leave the car and start walking.

Now we scramble up and over several old flows, stopping now and then to catch our breath and examine the weird shapes and patterns left by the lava—hair, fingers and toes, ropes and wheels. The black pahoehoe lava shines iridescently with a raku-like appearance, and I feel a potter's empathy with it. We hear tourist helicopters flapping overhead and know we are getting close. Off to one side I hear popping and crashing as trees topple and burn, engulfed by hot lava.

Then we see the river of lava itself twenty feet ahead. It is wickedly red, alive and primeval, a six-foot river of molten rock, silver in the middle and orange at the sides, snaking a pathway through the field on its way to the sea. I stand transfixed. This is Pele, or her manifestation, and I feel a stirring acknowledgment of her mysterious spirit. As I look into the red-hot flow, I also see in my mind's eye a concentration of all the kilns I have ever fired, and all the molten pots with their flowing glazes I have ever spyholed. Now I stand before the ultimate kiln, a cosmic piece of machinery at work firing its tectonic plates and restructuring the earth. I can almost feel Hawaii swell and grow as magma rises from the deep.

"Once you are awakened by the roar 52 of the volcano, you will never forget it," says Chiu as we return across the lava fields. "It is a roar like no other roar, not that of an animal, not that of a machine. It is the roar of the earth, a rumbling sound from the deepest depths. Its song becomes a mantra and the sky is aglow like a red arrow pointing in one direction.

"Hawaiian volcanoes are shield volcanoes," he says, "and relatively safe from explosions like that of Mount St. Helens. We do not fear to approach the crater during an eruption. I myself have gone down to the lava with friends and actually taken shovelfuls of molten lava and made a vessel of it. I put a scoop of lava over the end of a fallen tree, roll the tree over, put another scoop on the other side, pat it with the shovel, then put another shovelful on the base and gently work it into a natural form. The result is a container that looks like lava and might hold dried flowers. But it takes hours to walk there and hours to walk back!"

We make our long journey back to sit on the floor of Chiu Leong's new house in Volcano, a small township not far from Kilauea's caldera. Eva Lee, a dancer, serves us tea. "In the past five years," Chiu says, "I have not done much with local materials, primarily because of my sensitivity to island legends. Pele is a jealous guardian of her raw materials. She brings bad luck to those who transport her materials out. I believe there is a strong goddess on this island. I feel her power when she needs to express it. And she has expressed it quite a few times!"

I ask Chiu to describe his pots that are on display on boards at the entrance to the house. "I am primarily a raku artist. The glazes are basically washes of silver and copper in varying thicknesses to achieve different hues. I like raku because it is a primal source of energy, and thus close to the primal spirit of this living planet. Here in Hawaii we are in constant touch with the elements of fire, earth, water, and air, and they are in balance here. We live, smell, breathe, and bathe in these elements. Can there be a greater reality than a river of fire?"

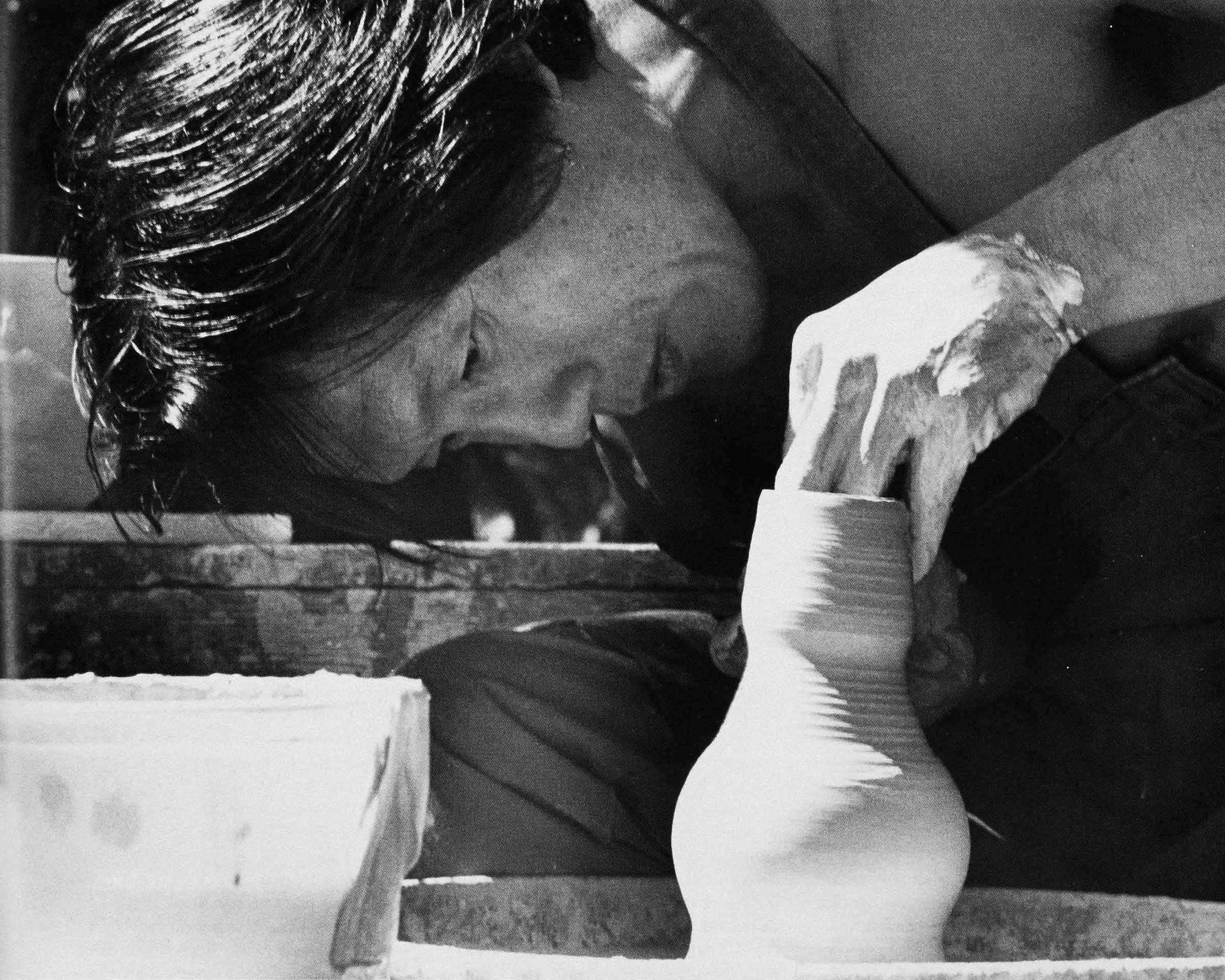

The next day Chiu is busy with his yard sale, so I take the long drive to Kona on the opposite side of the island to see some of Chiu's large pots. The road around the south point passes black beaches, crosses mountain slides, and looks down to the spot where Captain Cook was killed. Studio 7 Gallery in Holualoa is my destination. The modest gallery is operated by Hiroki and Setsuko Morinoue, who exhibit ceramics, prints, and paintings in a softly understated atmosphere. Setsuko, also a potter, shows me a large handsome pot by Chiu Leong, as well as works by Clayton Amemiya, Gerald Ben, and Ann Rathbun. She tells me her gallery prefers to handle objects with spiritual qualities, made by quiet, serious artists. In her opinion, much of contemporary art unfortunately is weak and limited only to technique.

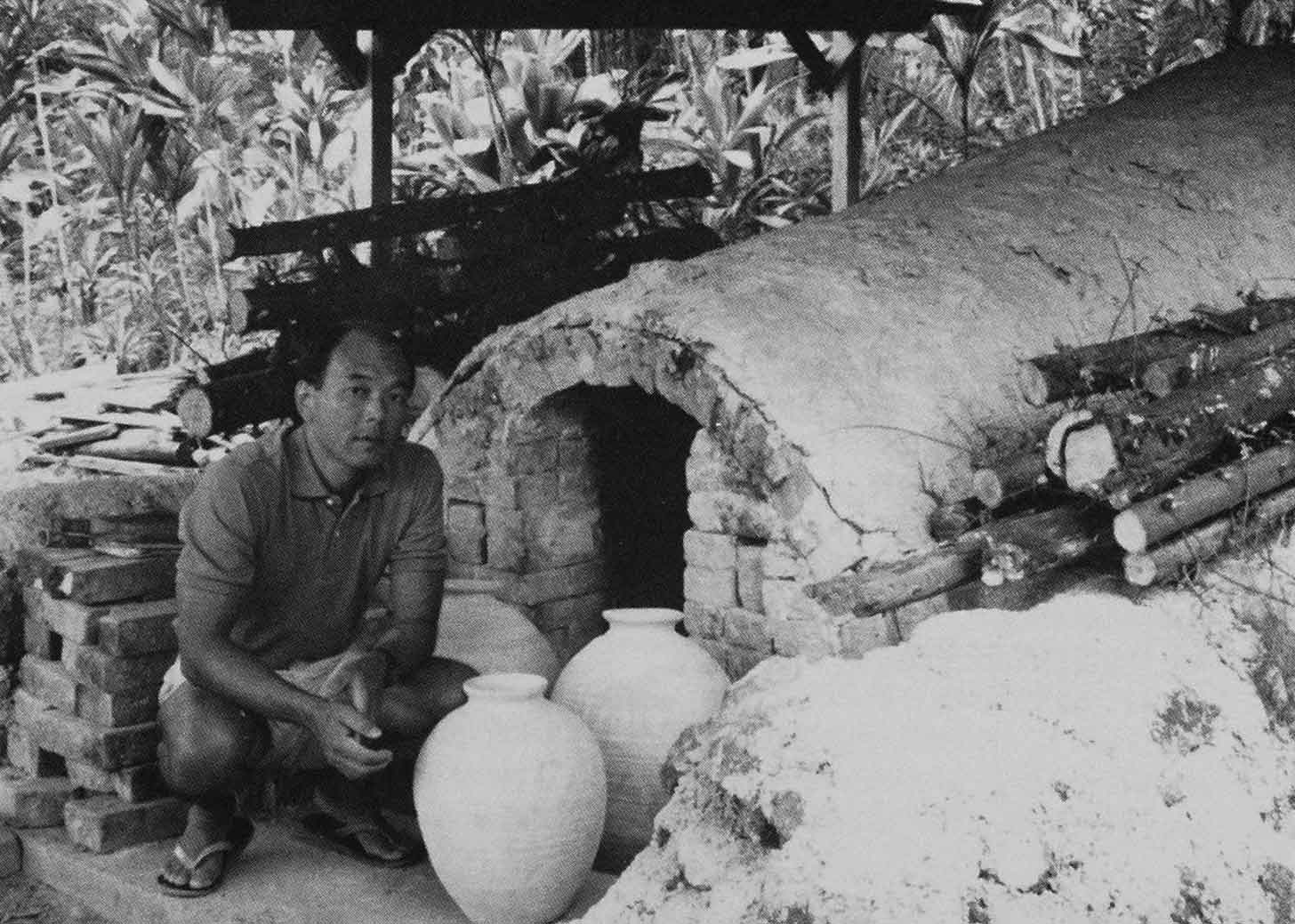

After leaving the Morinoues, I stop for pesto pizza at Kawailae, then continue circumnavigating the island, past Honokaa and Pepeekeo, arriving eventually at Hilo. Clayton Amemiya meets me at the Potter's Gallery run by Randy and Ann Morehouse, and drives me up the mountain to his home. Clayton has built an anagama kiln into the hillside behind his small studio. The kiln is 51/2 feet wide and 12 feet long inside, with the floor on different levels that slope upward at a pitch of about 25 degrees. Built from bricks discarded by a sugar factory, the kiln fires in 50 hours using a cord and a half of wood.

"I am influenced by rustic Japanese pottery as well as by rough, heavy Korean shapes," Clayton tells me. "I like a dark, weathered look to my pieces, with a fine coating of ash on the top parts. I prefer a heavy ash buildup on vases but not so heavy on sculptural pieces. I use driftwood in the kiln to give a salt glaze effect, and sometimes place coral or shells between the pots to give purple and pink tones to the surfaces. I don't use many glazes; basically a wood ash mixed with coral dust from the kiln-a traditional form of translucent glaze from Okinawa. I am strongly influenced by the Hawaiian environment, especially the patterns of sand on the ocean bottom and the texture and color of lava."

I return to Chiu Leong's house and start out for the volcano early on my last day. It is a clear, bright morning and a cold wind sweeps in from the northwest. We park the car and walk across the grassy plateau to the edge of the caldera. Steam rises around us from fissures in the ground—Pele's breath—as the heat meets the surface water.

Chiu suddenly suggests we take a steam bath. We strip off our clothes and climb down into a crack in the ground. On the very edge of the cliff we find a slippery, narrow ledge to stand on where the hot steam can billow up around our legs and heat our bodies. Six feet away and one hundred feet down, the volcano's caldera simmers ominously, a fermenting green soup of sulfurous rock and lava awaiting its next agitation.

I stand for a moment at the edge of the cliff looking through this window into Pele's heart. What cataclysmic emotions await eruption? What subdivision of homes lies unsuspecting in its path? I have brought her a small gift: the lei of green sweet-scented maile leaves grown in the highlands far away from civilization. When Al Lagunero, the Hawaiian activist on Maui, gave me the lei, he said the leaves should remind us that life is sweetness. I place the lei on a rock at the edge of the cliff and hope the message reaches Pele.

I had asked Al Lagunero at the time to tell me about the Pele legend. He looked straight at me for a moment, then turned away, embarrassed by the haole's ignorance. "Pele is not a legend from a faraway time," he said. "Pele is ongoing and living history. This aspect of the fire within the earth is a force within the creative nature of the universe. It is not a manifestation of the gods and goddesses as interpreted by

the Western mind.

"Pele embodies the female principle, what you call Mother Earth. In Pele's family, there are many sisters and these sisters are connected with growing things, with birthing, with the dance, with the sea. In other lands she is known by different names. We think of them mainly as family with whom we have shared this experience before, and equate them to the universal archangel."

Al Lagunero spoke of the Hawaiians' spiritual origin: 'This aspect of the fire, of Pele, is connected with the multiplicity of our beings. We have come from po in the time of great darkness. We recognize the nest of the void where we came from. We were birthed from the stars of po, from the blackest night, from the sacred night. Then we came to another place where the light is more lavender and eventually arrived in a new time and light to this planet where the skies are blue. There are different star systems that Hawaiians recognize as being the birthplace of our beings before we were brought here.

"We Hawaiians are not locked into linear thinking," he said. 'The multidimensional aspect of our knowing and the way in which we are part of the universe are things the spirit talks about. It is active all the time, never inactive. We have an understanding of the names and places before coming to Hawaii. The plains we came from were underground, and we came out of the pit into the time when the earth was made ready. Eventually we will go back to the original source from whence we came."

Standing at the caldera's edge with the lei, my mind returns to that evening on the balcony of Al Lagunero's apartment. I had leaned against the railing and watched the sun slip off the horizon line and fall softly into the ocean. It was a small moment, but a rush of feelings filled my heart: I wished I might stop the sun for just a second and prevent it from going down, or hold back the day that I knew would never return, and perhaps, thus, lessen mortality by a minute. The sweet insouciance of the evening, these new friends, my full days in Hawaii—it all seemed to pass too quickly. Meanwhile, in the living room, Al danced for some guests, undulating gracefully, interpreting the Hawaiian meanings by gestures and words.

Al had invited us to eat an authentic Hawaiian dinner cooked by his own hand. The table was loaded with fragrant dishes: raw crab, octopus, and tuna; pork and fish wrapped in taro leaves; dried tuna; bananas baked in the skin and served with coconut sauce; fern wrapped around vegetables; seaweed; a big bowl of po/; taro root and yams; and roast pork. Each dish and its history was carefully described, and then he invited us to the table to eat.

Remembering all this, I now reach down to pick up the lei, and toss it into the caldera.