Four funerals and a book: Writing The Teabowl: East and West

For a limited time, we're opening access to this article to everyone, regardless of membership. Most of our articles, including our archive of over 90 issues, are avaliable for members only to read (we've been publishing since 1972, and it's all readable online).

Membership is only $5 per month, and supports our work as a non-profit to publish articles and support ceramic arts.

Become a member today.

Writing a new book is like a new love. Initially, you find yourself infatuated. You can’t stop thinking about it, and you feel driven to talk about it. But the more you do, the more you see your family and friends’ eyes glaze over, and you decide it would be better for your real relationships if you divert your talking to writing. So, you do a little research and make a few notes. Perhaps you discover that you were seeing in your new love only what you wanted to see. You sit back and reconsider. Are you still entranced? If you decide you are, you take the next step – you move in together. Weeks turn into months and at times you wish you had never met your inamorato. If you are lucky, you reach the submission date, push the “send” button, and find that after months of labor you are still enthralled. That was my experience with The Teabowl: East and West.

Lunch, a contract, and a phone call

I am eating kleftiko at a little Greek restaurant in London with Alison Stace, the ceramics editor from Bloomsbury Publishing. We meet to talk about the possibility of a book on my PhD work, which was on touch, ceramics, and the physical engagement of the body. She likes the idea and asks me to submit a proposal. We settle up the bill. As she steps outside, she turns to me and says, “What I really need is a book on teabowls.”

The die is cast. Honestly, I don’t think I’m overly arrogant (self-doubt is a loyal friend), but my response is immediate. “I’m the one to write that book. I’m a ceramic artist, I write, and I am a long-time student of Japanese tea ceremony. When do you want it?”

“In nine months? Could you send me a proposal by next week? I need something authoritative but accessible. And not too ‘academic’.”

“Done.”

Fast forward three months. I’ve tackled enough research to send in a proposal. Alison has made comments, I’ve revised it, and re-submitted it. Two weeks later the Commissioning Board meets, and they approve it. Shortly after that, I receive a contract.

The next day I get a phone call from a much-loved aunt in the US, “You know how I promised to let you know if I thought it was time for you to come home to be with your mother? Well, it’s now.” My mother is ninety-two and, in recent months, she has become physically weak and breathless. When my aunt calls, Mom was already in the hospital having tests. I get the first flight out of Heathrow and all thoughts of teabowls and books are, for lack of a better phrase, shelved.

Four days later, my mother dies at home in the middle of a blizzard. One of my brothers, my aunt, and I are at her side. I stroke her face and whisper my love to her with her last breath, and I think that I have never before experienced such a privilege as being with her at that time. The two to three feet of snow outside causes innumerable problems, which means that we sit quietly for many hours before anything can happen or plans can be made. One thing that is sure – I will need to stay in the US for some time. A couple of days later I write to Alison, who quickly grants me an extension for the book.

My first priority is to find a place for my other brother to live. He had been living with my mother as he could no longer care for himself. In the end, this takes two months, which also gives us time to have the funeral and sort my mother’s things.

Work interrupted

Fast forward another three months. I am home in England, feeling utterly drained and emotionally empty. My mother was the kind of mom I could say anything to, and I miss her dreadfully. Also, I am sad that this vital link to my American soul has been severed.

I feel adrift.

For a while I spend part of every day watching mindless television. When I feel able, I begin re-reading the books I have at hand that relate to teabowls, and write short passages about using them in tea ceremonies. I always try to begin a writing project by putting on paper an actual experience or a physical response. Sometimes these make the cut, sometimes they don’t. The process helps me clarify what is important, sets the tone, and helps me get over one of my biggest challenges: Blank Page Syndrome. Actually, it’s a bigger syndrome. It’s also New Sketchbook Syndrome. And even New Body of Ceramic Work Syndrome. I find these initial steps hard to take. My internal censor is sometimes destructively harsh.

For a while I spend part of every day watching mindless television. When I feel able, I begin re-reading the books I have at hand that relate to teabowls, and write short passages about using them in tea ceremonies. I always try to begin a writing project by putting on paper an actual experience or a physical response. Sometimes these make the cut, sometimes they don’t. The process helps me clarify what is important, sets the tone, and helps me get over one of my biggest challenges: Blank Page Syndrome. Actually, it’s a bigger syndrome. It’s also New Sketchbook Syndrome. And even New Body of Ceramic Work Syndrome. I find these initial steps hard to take. My internal censor is sometimes destructively harsh.

Here are those first words, which ultimately end the book:

"You are seated in the tearoom. The warm colours of the unfinished walls surround you. It is quiet; the only sound is the soft, almost-simmer of the water in the kettle. The host has made a bowl of tea for you. You have performed the required thankful obeisance, and have turned the front of the bowl away from where you will drink. The teabowl now rests in the palm of your left hand as you cradle it with your right. You cradle the bowl that cradles the tea."

I’m pleased with this, but my husband Tony warns that the “cradling” reference is probably a “darling.” As in the writing advice, “Kill your darlings.” The expression means to take out the passages you fall in love with. They are often self-indulgent, and you’ll regret them a year or so later. In this case, the darling stays in. And thankfully, I still like it.

I then tackle the opening paragraph.

"As chanoyu, or tea ceremony, can be said to be one of the most Japanese of all Japanese arts, so the teabowl, or chawan, is often seen as the most Japanese of Japanese ceramics...Sometimes squat, plain, or appearing roughly made, the Japanese teabowl is enigmatic. Grounded in its function, but communicating something well beyond its utility, this simple form carries an aesthetic loading that translates into myriad levels of understanding – and misunderstanding."

I’m pleased with that. It will stay.

By now I am reading and reading – making notes and trying as best I can to keep them ordered, which I’m better at saying than doing. That’s because knowledge isn’t linear. You look for one thing and along the way you come across something else you will need later. So first, it’s a bit in early history. Then, it’s a passing reference to how teabowls are used and viewed. Then, a dip into philosophy. If you’ve gone into ceramics because you like a one-thing-at-a-time approach to life (throwing > firing > glazing > firing), this kind of writing isn’t for you. Chasing tangents is part of the enjoyment, but it can also be extremely hard to control, with notes here and there, and thoughts in all the cracks between. Interspersed in this research, I tap the keyboard and stare at the monitor for an hour or two each day looking for good examples of teabowls online. They begin to mount up.

Another couple of months go by, and there’s been a second difficult phone call. My brother-in-law, my husband’s identical twin, calls to say that he has had a relapse of his esophageal cancer and will have no further treatment. For about two weeks we are on the phone constantly with him and family. We drive my mother-in-law up to see him. We make a final visit.

He dies the following day.

It is hard on all of us, but particularly hard for my husband. Twinship is a relationship like no other. I write to Alison again and ask for a further extension. Family comes first.

When I am able, I’m working on the teabowl’s context within tea ceremony again, this time fleshing it out through the history of drinking tea and the development of chanoyu, tea ceremony. I love writing this. I am learning so much about tea, and intermingling fact and lore in a way I find pleasing. And of course, I am still searching the internet for examples of teabowls,

past and present. I’ve now set up Google alerts, so they are flowing in. I’m trying to sort out in my mind how new teabowls that aren’t used in tea ceremony, or often not “used” for anything, relate to traditional teabowls, which are concretely functional. What makes a teabowl a teabowl? Why is it special? Can new non-functional teabowls be called teabowls at all? If so, why? I tape a huge piece of paper on a wall in my office and draw a giant flowchart to explore the relationship. It helps but doesn’t resolve the issue.

I sit down at the computer with my files of compiled notes. I move the notes and texts around into the order they will appear, carefully taking the references with them, and begin to write. A bit of good writing advice comes from Anne Lamott’s book Bird by Bird. In it, Lamott gives us permission to create a very rough first-go, what she refers to as a “Shitty First Draft.” (SFD) I once heard the wonderful Takeshi Yasuda, a Japanese-born British potter, answer a question about sketchbooks. He said that he uses his sketchbook thinking that no one else will ever see it. It’s the same principle. The text for the teabowl in context is now in SFD form. I would like to spend time on it – correcting it, refining it, just enjoying the craft of writing – but as I’m already two extensions behind on this book, I know I can’t indulge. It can be fixed later.

I push on.

I already have the beginnings of a history of tea, and therefore the teabowl’s context. Next is the history of the teabowl itself. Looking at my notes, I realize I must give an overview of the history of Japanese ceramics first. I set about that. I love early Japanese ceramics, so this is not a hardship. I start at the beginning, with Jōmon pottery (c.14,500 BCE), knowing there is no direct relationship with that era and teabowls, but working on the premise that the aesthetics of Jōmon pottery live on into later Japanese ceramics. Plus, these “flame pots” are just such wonderful ceramic creations. Who wouldn’t take the opportunity to write about them?

Once I leave Jōmon pots, the history is mostly about Korean influences on Japanese ceramics, right up to the use of Korean food bowls as teabowls during the sixteenth century, considered by some to be the cultural height of tea ceremony. Called Ido bowls, these rough, flaring forms stand tall on distinctive foot-rings. They have an important place in tea ceremony and Japanese aesthetics. The most famous is called Kizaemon. Yanagi Sōetsu wrote about it in The Unknown Craftsman, which surely must be one of the most influential books in twentieth-century ceramics. Rereading his words all these years later (I first read it as a student), I cringe at his language (or the translation?), especially when he refers to the highly-skilled Korean potters who made these bowls as “clumsy yokels.” He also expresses their inferior status because “the rice they ate was not white.” Yet how he describes the teabowl itself grabs me, as it seems to speak so clearly of the qualities I look for in a teabowl when I use it as part of a tea ceremony.

“The plain and unagitated, the uncalculated, the harmless, the straightforward, the natural, the innocent, the humble, the modest: where does beauty lie if not in these qualities?” There is something in this that gets to the essence of the teabowl. It captures the simplicity of the form, yet hints at the profundity of its legacy and power.

I move from Ido teabowls to Raku bowls and their development in the 1500s. I write to Raku Kichizaemon XV, the Raku master of the day, and ask if I may include a photo of one of his teabowls. He doesn’t respond. That’s not surprising. My email is in English and he doesn’t know me. So I contact Nojiri Michiko, a Japanese tea ceremony teacher I know who lives and teaches in Italy. She is a friend of Raku. She writes to him and asks on my behalf. He sends an email back asking my view on various aspects of tea ceremony and teabowls. I work for a week to compose a response. A few days later Raku replies through Nojiri-sensei. She asks me to come to Belgium, where she is teaching, to discuss it. Why not? It’s about a five-hour journey by train from Cambridge. I leave early, and just after lunch I find myself walking up a steep hill in a dappled forest to Clerlande, a Benedictine monastery just outside the little town of Croix. This is where Nojiri-sensei is teaching. First, I must have a bowl of tea. It’s been awhile since we’ve met so I know Nojiri-sensei is checking out how I respond in the tearoom. She chats about Raku and their long friendship and about tea ceremony. I understand about three-quarters of what she says, which is a mix of English, Japanese, and Italian. After a bowl of tea, we sit and she translates Raku’s response line by line. She explains that Raku has a very specific and individualistic view of teabowls and tea ceremony, and that he doesn’t feel my book would reflect that philosophy well. He does not want a photo of his work included. I am, of course, disappointed, but not surprised.

Another phone call

During this time, along with writing and researching, I have been contacting ceramic artists to ask for photos of their teabowls. Sometimes, I get exactly what I need quickly. At other times, I am intensely frustrated because some potters don’t know enough about digital photography to send useable photos. Usually the resolution just isn’t good enough for print, or they’ve heavily manipulated it in Photoshop or some other software. I am so disappointed when I have a photo of a pot I love, which perfectly illustrates something I want to say, and I can’t use it.

Then there is a third phone call. My husband’s mother never completely rallied after the death of her son, and she is now failing quickly. We head over to be with her, and once again I am with someone I love to their last breath. I think I’m getting too much practice at this. I call Alison once again. This time I feel like I’m giving her a “the-dog-ate-my-homework” excuse. She gives me a third extension.

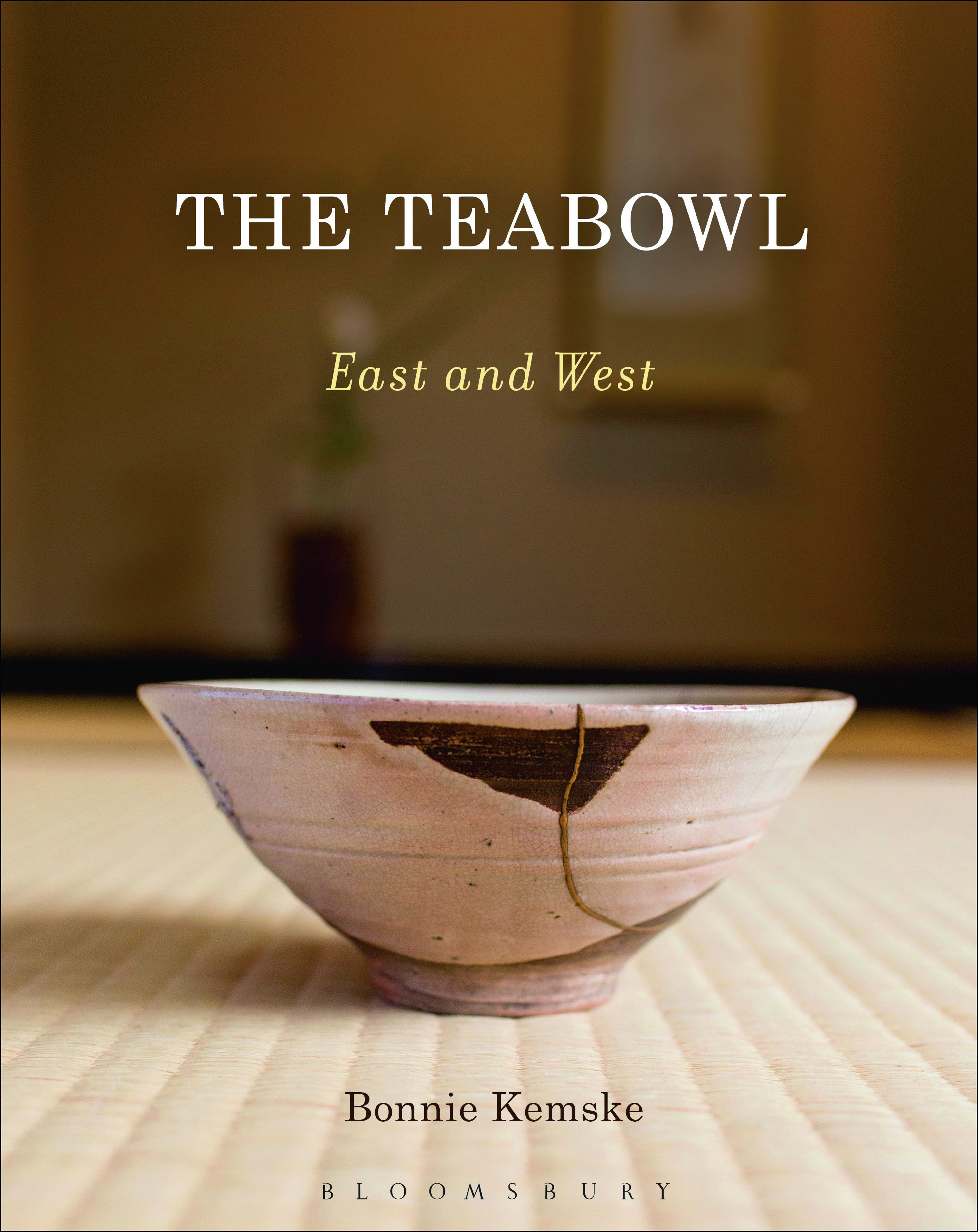

We are dealing with a lot of things, but when I can, I submerge myself back into teabowls. It is safe here. No one dies. I am writing about kintsugi, the Japanese lacquer and gold repair that is often found in old, revered teabowls. In kintsugi the cracks and joins appear to be solid gold. I am thinking about it not only as technique, but as metaphor. This is a sad time in our lives. Kintsugi reminds me that sometimes things that are broken are put back together in ways that are stronger and more beautiful than before.

I begin to pull together the photos from contemporary artists. I do a quick analysis of each pot, noting its characteristics. Then I sort through these, looking for aesthetic threads. In this way I tease out what makes these new teabowls non-traditional. They may still be teabowls but there are indeed differences: the use of porcelain, since this is not common in present day tea ceremony; the use of building techniques not normally used in Japanese teabowls (e.g., slab-building); differences in firing (post-firing reduction, smoke-firing, and salt-glazing); non-Japanese surface decoration or treatments (heavily applied texturing, English slip-trailing, the use of terra sigillata, and unusual graphics, including decals and transfer prints); and the use of multiples and the incorporation of teabowls into ceramic performance art.

Most striking is how Western potters have used the teabowl as a canvas for expression. I laugh at Philip Eglin’s teabowl that has popes and pin-ups on it. I am near tears when I come across Alastair Whyte’s Hiroshima (2014), which he made in memory of those who lost their lives to the dropping of the first atomic bomb; he incorporated human ash into the red glaze. And I am in actual tears when I read about Steven Branfman’s installation, A Father’s Kaddish: The Celebration of (a) Life in the Aftermath of Death, where

he made a single teabowl each day for a year following the death of his son, Jared. These last two remind me why I am so captivated. Because the teabowl carries with it such rich connotations of ritual and reverence, it exudes a quiet strength that gives you a sense of the monumental held in the hands. The struggle with photos

The fourth painful phone call comes as I am beginning to write the “Introduction” and “Conclusion.” It is from the residential home in the US where we found a place for my brother to live. He had been very happy there; making new friends and fully part of the community. But after many months, he developed congestive heart failure. He didn’t last long after that. Back to the States to help with arrangements and say goodbye. One last call to Alison for the fourth and final extension. While on the phone she tells me that Bloomsbury is re-structuring, and that Ceramics will be incorporated into the Academic Department. Oh, and her job no longer exists.

So I am back in the UK. I am writing frantically, constantly wondering what has been missed in this often-interrupted project, but pushing on. A full rough draft is an important milestone. Tony and I celebrate with pizza and a beer. The final draft seems almost anti-climactic after that – but we celebrate again anyway. I’ve been working on photos throughout the project, but now it’s crunch time. There are 103 of them. All require permission for use. Some require three permissions – artist, photographer, owner or gallery – each with his or her own form to print, sign, scan, and return. I’ve hired help with this and am thankful for it, if for no other reason than I detest computer spreadsheets, where all this information must go. I write a check to the woman helping me for more money than what I received to write the book.

The submission date arrives, and the whole package – text, photos, permissions – is duly sent off to the editor in the Academic Department to whom the book has been assigned. Fast forward a couple months. The editor has clearly not understood the brief I was given for the book – “accessible”, “not too academic” – and she has sent the book out to three academics. Since they think they are reviewing an academic book, the reviews aren’t great. Some comments I welcome and set about incorporating these immediately, but there is little I can do to make a non-academic book into an academic one. They are different books. I email the editor to explain this, and add that I am not interested in writing that book, at least not at this point. I feel I have lived with the writing of this teabowl book long enough. I re-submit the text with the minor revisions and the editor sends it out again, but with an explanation about the aim of the book. This time the reviews come back positive. We’re off and running!

Next come design decisions. This is one of the stages I really enjoyed when I was editing Ceramic Review, and I find this just as pleasurable. Then the proofs come in. Proofreading isn’t much fun, especially when it’s my own work. I constantly feel the urge to improve the text, which cannot be done at this stage. Then I sit with the proof and construct the “Index.” That’s not so bad. It makes me realize just how much material I’ve managed to squeeze into the word count.

The launch

The book arrives a month before its launch date. When I answer the postman’s knock, I’m so excited I jump from foot to foot like a six-year-old. But then there’s a shift. I open the jiffy bag very, very slowly and carefully. It’s like opening a kiln. Will it be good? Or will I be disappointed? The book slides out of the bag into my hands. And I am pleased. It feels right. It looks right. It was a good firing.

With more changes at Bloomsbury, The Teabowl has found a new home in their resurrected imprint Herbert Press. The new editor, Jayne Parsons, is eager to work with me. The book’s first outing is a lecture I give at the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation in London. It is well-attended and the questions at the end are good ones, which bodes well. This is the first of about twenty talks I do in the UK and US. I speak to potters, tea ceremony practitioners, gallerists, students, collectors, and the general public. For one talk, only six people come and they eat their lunch while listening to my lecture. At another, the auditorium is full, with people standing around the outside. I enjoy both experiences, and every one in between.

While doing these lectures, I am, of course, absorbed into a world of teabowls, but inside I’m beginning to feel the excitement of a new interest. I am thinking more and more about kintsugi. Before I even realize it, I am smitten. Is there a book here? I’m a little hesitant. After all, it took four funerals to get to the end of The Teabowl: East and West. But kintsugi now has a hold on me, and when I finally mention it to Jayne, she pounces. Before I know it, a new book is underway.