A Flameware Journey

As I was thinking about this article, I decided to Google "flameware." Aside from Ron Probst's informative and generous article in Studio Potter (Vol. 2, No. 2, winter 1973-74), what I mostly read was to stay away from this material for a variety of reasons, including, and most emphasized, the litigious nature of our society I also read about rules for working with flameware clay bodies, including what materials to use in glazes (and that no glazes should be used at all), firing temperatures, and the structure of pots made from flameware clay. Though some of the points made would have been helpful in hindsight, I am grateful I did not read all this before I embarked on my own flameware journey. Ultimately, I needed to find my own way.

The historical precedent of using low-fired clays and the contemporary possibilities of high-fired cooking pots have intrigued me since I began making pottery, but I learned about flameware during six weeks working with Karen Karnes in her Morgan, Vermont studio. The clay body, glaze recipes, and encouragement to explore the possibilities were passed to me in a somewhat formal manner that snowy winter of 2001-2. Having received this blessing, I found myself standing in my studio thinking, "Oh my God, now what?" After several months of wavering between the stoneware pots I had been working on and the big step of bringing flameware into my studio, I committed to working in flameware. I was interested in going beyond the casserole, so I began to try out which cooking-pot forms could be translated from metal or low fire clays. I spent time in kitchen stores examining cooking pots, then went back to the studio to work out some of the technical issues. I continued to make tableware, but found that the challenges specific to making pots used from the oven to the table really caught my attention.

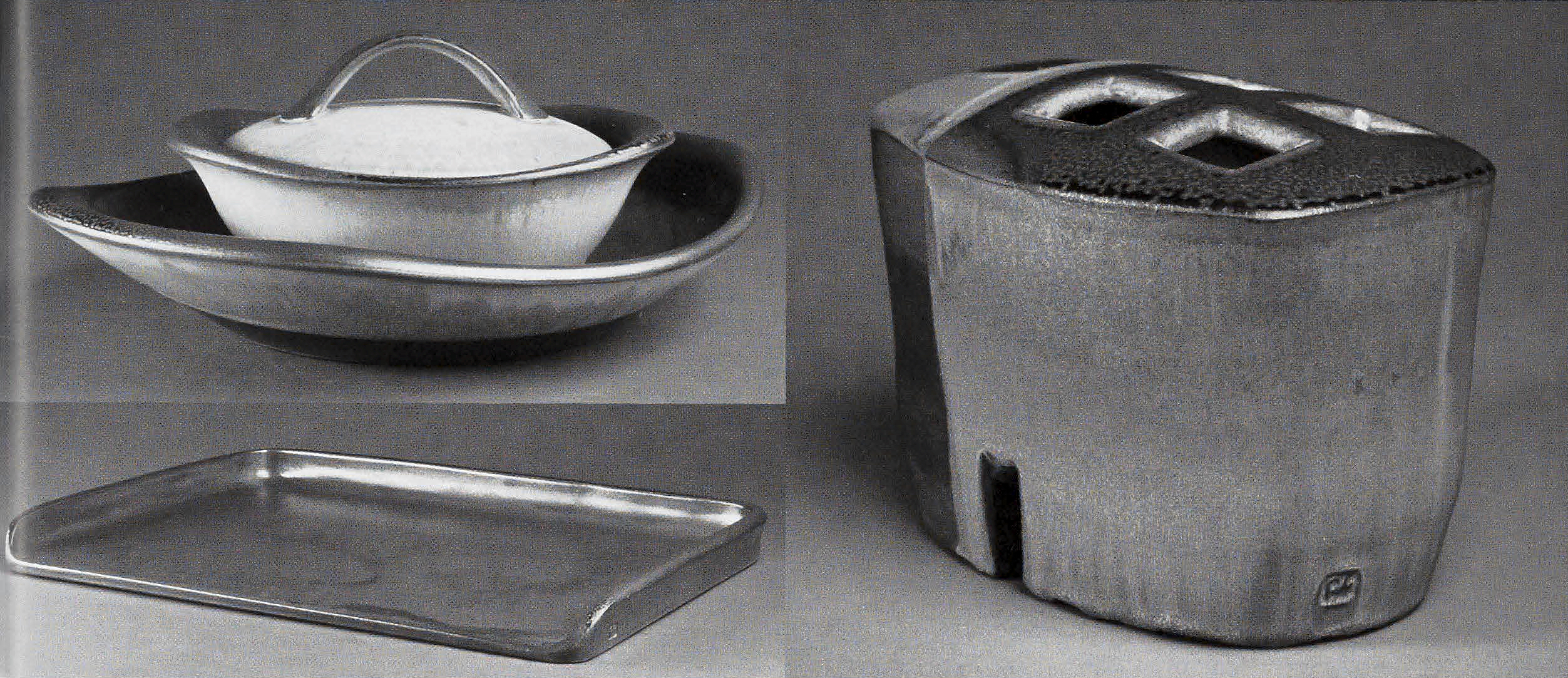

A whole new vocabulary of form and function developed in response to the strict parameters of utility for pots directly exposed to high heat. I needed to eliminate sharp edges that would promote shivering, while maintaining integrity of line and form. The galleries of the covered pots had to allow a smooth path for the serving utensil; the handles needed to be placed high, away from the heat source and secure enough to use with potholders; and the handles on the lids had to be grab-able while extremely hot. All this needed to work together for utility and be beautiful, even elegant. As I worked out the technical problems, what emerged were sculptural forms for ovenware. I found that the process of distilling my ideas, both functional and architectural, about cooking pots began to define me as a potter.

I also had to deal with the balance of thickness and evenness in the structure of the pots, and with avoiding uneven tension between the glazed interior and exterior if I wanted to allow some of the pots to go naked and reveal the beautiful color of the clay. A few returned pots early on required me to re-think and re-work some of my forming techniques. At first I used a slight roll to finish the flat bottoms, for a visual lift similar to my stoneware pots. The roll encapsulated a bit of air, but as these pots were used and washed, little pieces of the pot spit off. The thickness of this roll also expanded and contracted at a different rate than the thinner bottoms. I had, of course, always wadded my pots for firing in the soda kiln, which was fine at cone 9. But I found that a hot cone 10 strengthened the pots and made the clay body more beautiful.

At this temperature, the flameware clay becomes soft and the wads make shallow divots in the pots. All these, factors led to cracking on the wide bottoms of the round as well as the altered forms. I worked on correcting the forming flaws, stopped using wadding, employed an alumina-saturated wax for the bases, and made sure to use my Advancer kiln shelves (because they do not warp), especially for the large flat-bottomed square and rectangular bakers. I then tested my pots, putting them through a series of extreme temperature changes. I poured rapidly boiling water into the pots and put them directly into the freezer. I allowed the pots to stay in the freezer overnight, where they froze into solid blocks of ice, then put them directly into a preheated 450-degree (Fahrenheit) oven. The ice slowly melted and began to boil again. I felt confident that this work had passed an important test and was ready to be offered out into the world.

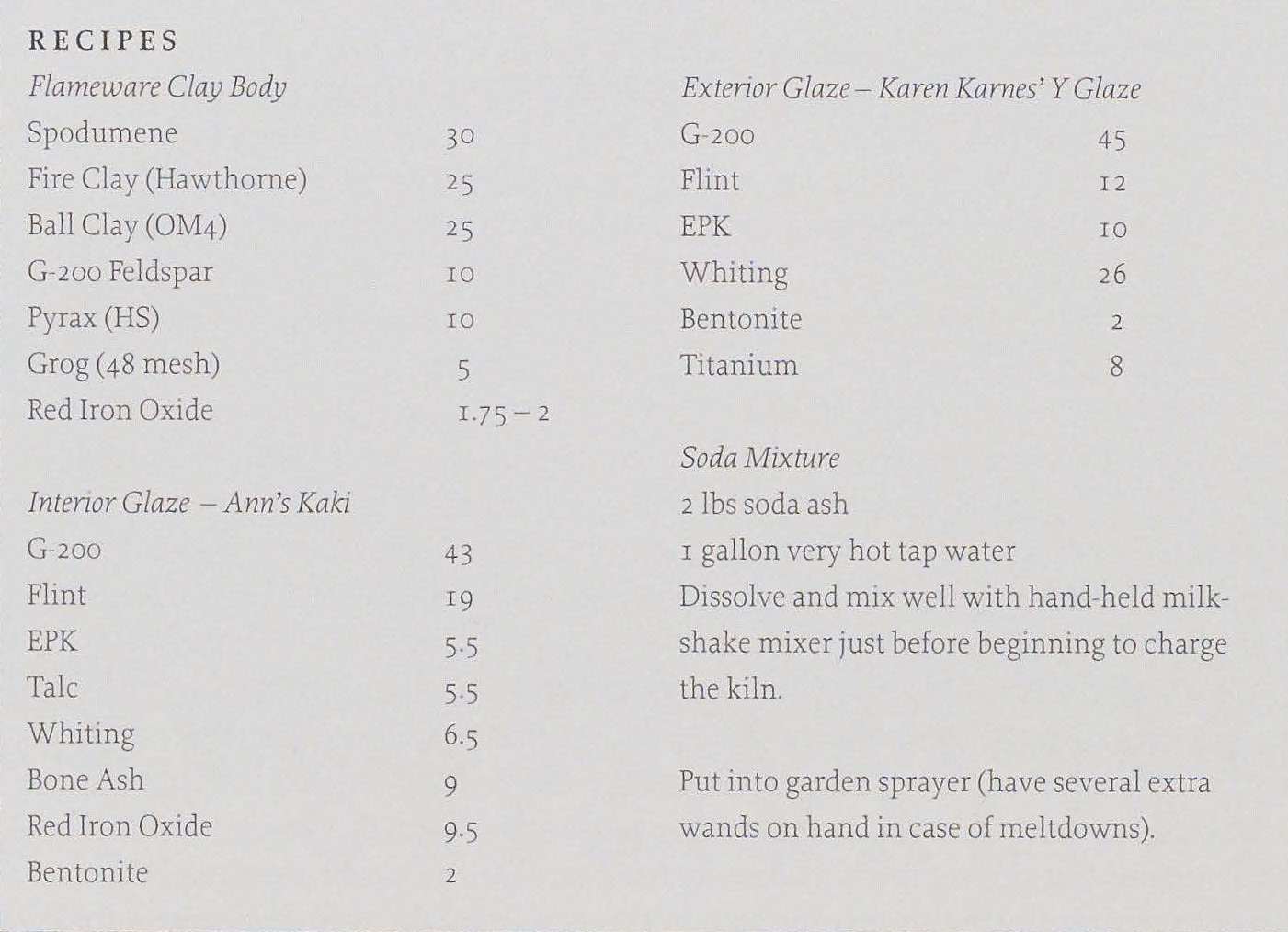

The clay body I am currently using, with the low coefficient of expansion necessary for high-heat cooking, is a result of research and testing by many people, including Mikhail Zakin, Karen Karnes, M.C. Richards, Bill Sax and Ron Probst, as well as the ever-changing availability of ceramic materials. When the "dirty" gray spodumene with some iron content (< 1%) became unavailable, potters had to switch to the pristine white spodumene from Australia. I add from .75 to 2 percent iron, which gives a beautiful body color in my kiln and no carbon coring in heavy reduction, but also does not allow these pots to be used in a microwave oven (though since I do not use a microwave I have not really tested it). Although I have customers who say they put my pots in the microwave, I do not recommend it because of the iron content in both the clay body and my liner glaze. If applied not too thin or too thick, this glaze works quite well, has a coefficient of expansion similar to the clay body, and cleans up from greasy, sticky, burnt foods like nothing else. When I use an exterior glaze, I use only one: "Y" Glaze. Karen Kames used this glaze in a variety of colors on pots fired in her gas reduction kiln. I changed it just a little for one color, a golden titanium yellow that sometimes gives a small blue jewel in a drip or line (the scorned rutile blue, if you can believe it!).

Perhaps my most challenging technical issue was the firing process. I have soda-fired for years, using wood to accomplish body reduction, and wanted to use thiS| flameware body in the atmospheric firing. To my knowledge no one had successfully soda-fired flameware for high-heat cooking. My clay formula contains high amounts of lithium in the form of spodumene, so I needed to experiment with the amounts of soda I used. After several firings with mixed results, I found I could use a small amount of soda (about a pound and a half soda ash dissolved in hot water for my 70-cubic-foot kiln) sprayed in short bursts, allowing the kiln to breathe well between charges. If I was heavy-handed with the soda, the result was shivering edges rather than a lightly-stippled flush. The clay body in my propane-fueled soda/wood kiln is a rich mahogany to a dark cypress red.

I have now worked with flameware for a bit over six years and moved my studio and life across the country. I have made covered casseroles, kettles, hearth-cooking pots, oven/pizza stones, rectangular, square, and oval bakers, and roasters in many sizes, plus woodstove humidifiers - some with subtle glaze variations, some naked with soda-kissed surfaces. Many of these forms were initially made for customer requests, which has been fun and challenging - - ideas I would not have thought of, but that gave me artistic license to develop a certain kind of pot used for cooking in a particular way. I care deeply about the foods we eat, where it comes from, and how it is prepared. I have looked at cooking pots from many cultures and times. I have had a fabulous and sometimes frustrating time on this flameware journey. I love making these pots.

As I am now at a crossroads, however. Although I love making them one at a time, I must consider the price point on these very utilitarian pots. I sell them wholesale to galleries and retail in my studio, and in between at pottery shows and other venues. I think these pots are resolved and I feel I am almost done with them as a series (though I will love to continue to work with customers' ideas and maybe some of my own). I am ready to take what I have learned from this work and move on to the many ideas residing in my head and notebooks. Yet I believe I have a viable, well-designed, sellable "product."

So I have been pondering and exploring whether to "manufacture" - yes, massproduce - in limited editions for the high-end gourmet food and kitchen tools market. So far, I have found out that the flameware can be Ram-pressed and that there is a market out there. I am still investigating how to approach that larger market and how to go about getting my pots Ram-pressed outside my studio, because I do not want to remain the manufacturer. Nor do I want to send the project overseas, for a variety of reasons including the need to see the process through from the pressing to the firing, anticipating some hands-on participation especially at the outset, and preferring to work within my own community. One dream is to create a small manufacturing facility

in my hometown. Wouldn't it be amazing if a somewhat-poor studio potter could really support herself with a series of pots that took years to develop, and still be a full-time studio potter, but perhaps not so poor?