Drawing as Intelligence

Intelligence is the ability to learn and understand, and drawing provides a means of giving form to thoughts and feelings. To reason and remember, to relate and to order are intellectual activities which allow us to structure experience. Out of this structure we conceive thoughts and feelings which give rise to the need for expression. Language functions as a primary means of expression, a vehicle for communication and comprehension through the use of words. Drawing has a similar function through visual means. Although drawing is not commonly thought of as a manifestation of intelligence, it is in fact an intellectual exercise that allows an individual to use visualization as a way to understand and project concepts— apprehension.

Visualization is a mental process associated with thinking. Everyone can mentally see or picture points in time (last Christmas), or things (the dress worn to a high school prom), or a skill (driving a car). Creating mental pictures is basic to human consciousness. However, as Mike and Nancy Samuels point out in their book, Seeing with the Mind's Eye, "It would seem that the use and development of visualization has occurred in inverse proportion to the development of language and a written structure for recording it."1 Certainly visualization has been neglected by the standard educational systems. As a result, although everyone is capable of visualization, only a few individuals 36 apply it. It is clear that there are people who either by habit or genetic code rely heavily on the intellectual process of visualization in order to learn and understand. The visually oriented person collects, organizes, and analyses visual evidence, both real and imaginary, in an attempt at mastering and sharing experience. The dependency on visualization as a primary way of knowing has caused many of these individuals to become artists, frequently not by choice but by necessity. Drawing is for them a principal reasoning tool. It is the most direct and leanest instrument available to the visual artist. Drawing is a way to explore objective reality as well as to focus imagination. Edward Hill writes in his book, The Language of Drawing, "Drawing diagrams experience. It is the transportation and solidification of the mind's perception. From this we see drawing not simply as gesture, but as mediator, as a visual thought process which enables the artist to transform into ordered consequence what he perceives in common (or visionary) experience. For the artist drawing is actually a form of experiencing a way of measuring the proportions of existence at a particular moment."1

The laws of optics and the systems which have been invented to aid exact reproduction of what the eye sees are irrelevant to drawing for the artist. Visual interpretation and explanation of the experience of seeing, thinking, and feeling are what counts. As Henri Matisse aptly put it: "I have never considered drawing as an exercise of particular dexterity, rather as principally a means of expressing intimate feelings and describing states of mind."1 An imitation or copy is always a poor substitute for the original, be it another work of art or an aspect of substantial reality. Drawing as a cerebral form of analysis moves away from imitation toward revelation and insight. Observation directs the act of seeing and through drawing searches out evasive images, concepts, and the external relationships beyond appearances. Moving beyond appearances and assumptions toward truth is a goal long associated with art.

A significant part of the artistic truth or artistic revelation of any drawing is the result of the materials used and how they are manipulated. The lines and marks themselves made with pen, pencil, etc., plus the surface drawn on become an irrevocable part of the visualization process. The materials constitute a medium through which the artist realizes an ! image. As the drawing itself becomes part of what is seen, the artist selects and builds on the possibilities presented, using the reality of the drawing to derive a clear perception. A deep understanding of the material means in concert with an intense visual penetration of the image sought will bring a drawing into the realm of immutable fact. Like a shell, a rock, or a leaf a good drawing has a metaphysical presence, an unfathomable, unquestionable lightness which could be called perfection. A total fusion of physical means and image or idea lies at the heart of all important works of art. Artistic revelation involves the establishment of an explicit parallel between what is seen or imagined and the material means at hand.

In considering the idea of the explicit parallel, it is interesting to take it a little farther and reflect on the often-heard Chinese Zen expression-in order to paint bamboo one must become bamboo. This implies that the artist must create a parallel within his self between the human spirit and the organic growth and form of the bamboo. Once this parallel has been achieved, the painter does not transform nature into art but taps the flow of the absolute where the painting and its subject (bamboo) share the same meaning. The artist strives to stand at the junction of the spiritual and the material. Spiritual at first may suggest only an ecclesiastical principle. It is, however, legitimately used also as a term to define incorporeal functions or experience. Used in a secular way spiritual or spirit might clearly be equated with intelligence. Therefore, in addition to other definitions, drawing could be looked upon as a direct invocation of the intellect or spirit of the visual artist.

Lewis Hyde writes in The Gift, "An essential portion of any artisfs labor is not creation so much as invocation. Part of the work cannot be made, it must be received; and we cannot have this gift except, perhaps, by supplication, by courting, by creating within ourselves that begging bowl' to which the gift is drawn."1 Drawing is an external procedure analogous to Hyde's "begging bowl." The artist may produce drawing after drawing of the same thing, over and over again trying to establish the truest connection between observation, memory, intuition, reason, and the physical limitations of materials and processes. Like the runner who endures pain to reach what is termed the "runner's high," the artist longs to achieve the gifted state where the work comes easily with increasing levels of clarity as it floods the studio with energy and power.

The principle of the explicit parallel is central to my own work as a ceramic artist. The parallel between realities and the psychic self is illusive, although as an artist who uses clay, glaze and fire, I must say that I feel a strong empathy or affinity for the materials and processes of ceramics. I've always thought of working with clay as a kind of collaboration. Clay has a mind of its own. You can't reason with it verbally or just physically force it to obey. You have to get in on its wavelength and make your moves at the right time in order to accomplish your objectives. Working with the fire is definitely similar. My experience with the raku process has taught me about timing which, ultimately must be based on intuition.

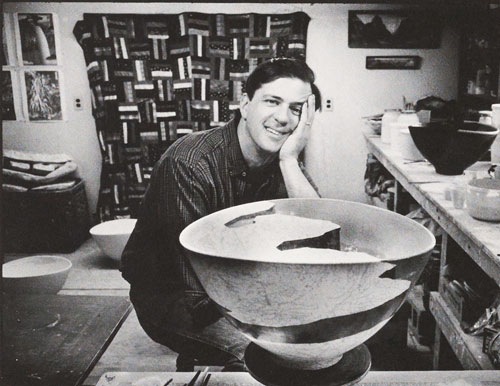

The explicit parallel between image or idea and means is somewhat less abstract. At least, the relationship can be easily articulated in the case of my own work with the vessel. For the past several years I have been exploring the possibility of a parallel between the bowl in association with a landscape image and the human figure in space. I have worked and reworked this parallel in an effort to describe to myself the nature of an imaginary place and to understand the phenomenon of mapping three-dimensional form. Early on in this exploration I began to feel somewhat sure about the imagery because I had worked with it before in other ways. The intriguing part has been the continuing problem of the bowl form as a surface and, of course, what the solutions to this problem have revealed about the realization of a mental picture. The physical confrontation with the concave and convex walls of the bowl through the use of line as an extension of image disciplines my imagination, freeing me from merely impulsive solutions. The drawing-discovery process keeps the imagery from becoming an ornament or a formula. I strive for unity and a quiet coherence or calm which comes from a connecting and reconnecting flow back and forth between the reality of the form and the illusionary landscape. The bowl is empty but full.

Drawing has been the key to unlocking the mysteries of the bowl and the image. I have been engaged in a complex problem which uses drawing as an instrument for understanding. Line can be seen as the thread of my intelligence reaching back into childhood and gradually weaving a structure for the present. The bowl series serves as a kind of vortex for this line. The bowl is me personified. The landscape image is my sense of place and the drawing or line that connects it all is my curiosity seeking to comprehend relationships, searching out thoughts and feelings, unifying surface and form, and trying to uncover meaning. As a visual person I depend on drawing as a way of knowing. I draw to learn and understand.

Notes:

1. Samuels, Mike and Nancy, Seeing with the Mind's

Eye, New York: Random House, Bookworks Book, 1975.

2. Hill, Edward, The Language of Drawing, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966.

3. Flam, Jack D., Matisse on Art, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1978.

4. Hyde, Lewis, The Gift, New York: Vintage Books, 1983.