Crossing Over

There are lifestyle myths related to being a studio potter that enchanted me when I first began. They varied from "country potter with vast gardens and rambling house" to "urban artist potter with loft studio working toward international exhibitions for enthusiastic collectors." In reality, what I loved was the freedom to work in solitude at my own pace, making the work that interested me and exploring the infinite nuances of surface and form within the context I had created. For years I happily worked as a studio potter: making pots daily, carving and glazing to the sounds of National Public Radio. I made modern forms carved in contrasting black and white. People wanted to buy my work, and eventually demand grew to exceed what I could make.

I became hemmed in by what should have felt like success, and my freedom eventually became my prison. Ideas for new work piled up in notebooks, and responses to museum visits and other inspirations were left unrealized. My work traveled, but I stayed home to make the pots. From the visibility and number of my pots, some people thought that there was a big operation behind me. In reality it was just me and an assistant, working nonstop. I admit that I liked the repetitive work and labor that are so integral to making ceramics, what Jonathan Adler once referred to as "making the doughnuts." I find the never-ending daily tasks meditative and fulfilling... up to a point. Now, though, I was craving more diversity of activity: time and space to follow the thread of a new idea as it came up, exploration of other media, enriching travel, and the satisfaction that comes with teaching. But there was no time!

During a show in New York in the 1990s, I was approached by some companies about designing for them. I was intrigued. I hoped this would provide the opportunity to diversify and change the way I worked in my studio. I did some designs for Dansk, Tiffany, and later, Crate and Barrel. The collaborative aspect was fantastic: an intelligent exchange of ideas concerning market placement, design, and function. The prototypes I made, using the same techniques I employ in my studio work, were helpful for all the collaborators involved in realizing the designs, from buyers and their company CEOs to factory managers and regional agents. It was interesting to see how knowledgeable they were about ceramics in general and to observe them handling pots with the same admiration I usually see among potters. The revenues from this venture were small, but the experience extremely worthwhile and challenging. It opened the door to other possible ways of working, and around the same time I was invited to visit an artisan ceramic studio in Peru in order to develop some designs.

It made sense that having some of my pots made in Peru could provide income that would free me up to explore new ideas in the studio at home. The Peruvian studio Jallpa Nina, just outside Lima, is an artisan-driven workshop in a beautiful setting, employing talented and skilled potters. The tableware designs they produced for me from local materials were beautiful and well-made. Sadly, once back home I found myself becoming a marketer and salesperson, spending my days surveying Excel inventory sheets instead of working in the studio as I had envisioned.

One day I just had to stop. I was barely making ends meet. The demand for my work had subsided, and I could see a shift in business practices on the horizon, with less distinction between American handmade ceramics and internationally designed factory products. I decided to take a creative sabbatical, giving myself a year, or as long as my savings would allow. I wanted to continue working in the studio, but in an open-ended way.

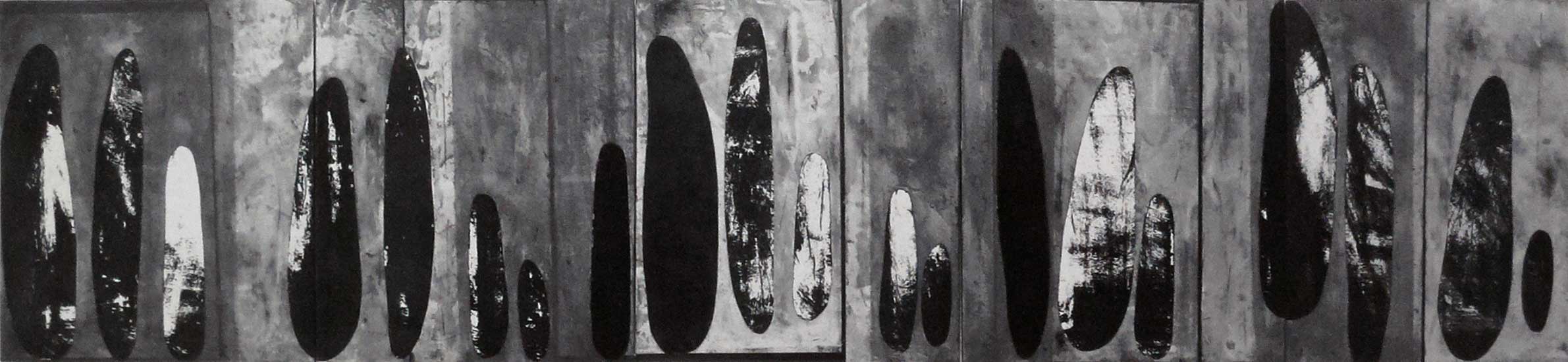

I made some large slabs to work on and was set free. The slabs served as a ceramic canvas, with slip and glaze as my paint and pigment. Texture and strong color appeared, and I was basically painting now. I began to work out some of the compositions on paper, which led to other related works on paper and to monotypes. Still exploring and investigating, I became interested in texture and began adding rough-textured glazes in strong neutral tones to the slab/tablet paintings. Then, surprisingly, I started thinking about vessels again. The shapes in my painted compositions suggested vessel forms, and the textured glazes could be interesting stretched as a skin over a three-dimensional form. This led to a series of thrown and altered vessels with textured glazes.

After what turned out to be a more or less three-year sabbatical, a multifaceted body of work has emerged from my studio. I now move between mediums according to what best suits each project. This includes vessels and paintings on clay tablets, installations comprised of dimensional ceramic squares, and monotypes on mulberry paper. My ideas and activities are no longer driven exclusively by clay. Last year, I had two solo gallery shows, and I still do design work. When I am designing tableware, I think of it as a service for specific clients. I teach a little and sometimes serve as a design consultant for nongovernmental organizations with potters in developing countries. Being of service has allowed me to connect with the world in a manner that is totally opposite that of my solitary studio work. Sharing my ceramic knowledge, learning about other cultures through complete immersion, and the break from the studio have all helped me gain a more global perspective in my life as an artist. I am exhilarated by the variety of experience and activity, even with the extreme economic uncertainty it brings. Each aspect of my work informs the others, and I notice a great deal of cross-pollination. Garth Clark commented to me recently that an artist can no longer work in just one medium. I nodded in agreement; I think his comment goes well beyond art, applying to many categories in modern life. I am no longer interested in tiresome conversations about art versus craft, or sensitive to the labels of designer, potter, or artist. I am all of these.