The Clay Hierarchy

Come, replenish your starving bodies from a White chef, a White capitalist experience, and, most importantly a White dish. Spend your last dollars on this fun night out. Move the porcelain platter closer to the perfect angle where the light hits it just right. After all, we must post for the world to see. Everyone needs to witness the gatekept food that only the bourgeoisie can enjoy. I mean, if we can’t post it, the experience won’t taste as good. The food won’t dance along the tastebuds as much as it should. Hell, I didn’t buy just the food. I bought the commodity of the experience. I rented this white gold for a little under two hours, so I’ll be damned if I can’t present the white crown of clay to the world. They must see it. I want them to. What else am I, if not a consumer of White supremacy?

I’ve had a short life, half of which I was a mere adolescent looking to be nurtured. In the other half, I was a silent observer in academia, eagerly waiting to escape. Thankfully, the arts acted as that getaway. I can remember the high school dances where I’d retreat to capturing the night on a DSLR and the long winters I’d spend on the wheel. The rebellious phase, which I’m proudly still a part of, was spray-painting in San Diego and seemingly never finding the time to write about it. The concept of creation was always just a byproduct of my seminal tendency to observe. Alongside that foundation of noticing the unseen, undesired, or unsaid, I, like many of you, endured a country’s historical failures. Hence, I used to choose blissful ignorance. If it didn’t happen to me, it didn’t matter. It was selfish, but also conducive to staying afloat during a time when Black death cascaded through social media, pandemics shattered families, and the world continued to burn.

Indeed, it’s difficult to feel, but scarier not to feel at all.

There was not some particular moment when my life changed, rather it was a culmination of talking to genuine people, feeling like I was selling my identity for profit, sleeping on a couch for a year, and frankly, having a couple of mental breakdowns that led to change. While those are bottled conversations for a different day, the experiences altered the lens I chose to perceive the world through. As of late, I’ve noticed a familiar stench in the one medium I could always call home.

There is a hierarchy in clay and it’s oddly reminiscent of racialization in America. I don’t think one academic field can explore, nor justify, such a blanket statement. So, I’d like to implement several: rhetoric, psychology, color theory, and sociology to give a brief taste of a potentially endless field of study. I chose these fields as rhetoric demonstrates how we uphold this clay hierarchy, psychology and color theory can justify our colored associations within clay and race, and sociology elicits how society cyclically perpetuates this problem. I’ll also examine the work of a handful of potters and sculptors whose thematic concepts allude to this hierarchy.

While I believe some studio potters aim to dismantle parts of the clay hierarchy, I’m under the impression that the majority aren’t even aware it exists. I apologize if you anticipated a placid read, but I hope we’ll begin to cremate clay’s colonization.

Let’s begin with color and progressively zoom out.

Why can’t we unsee race and color or race in color?

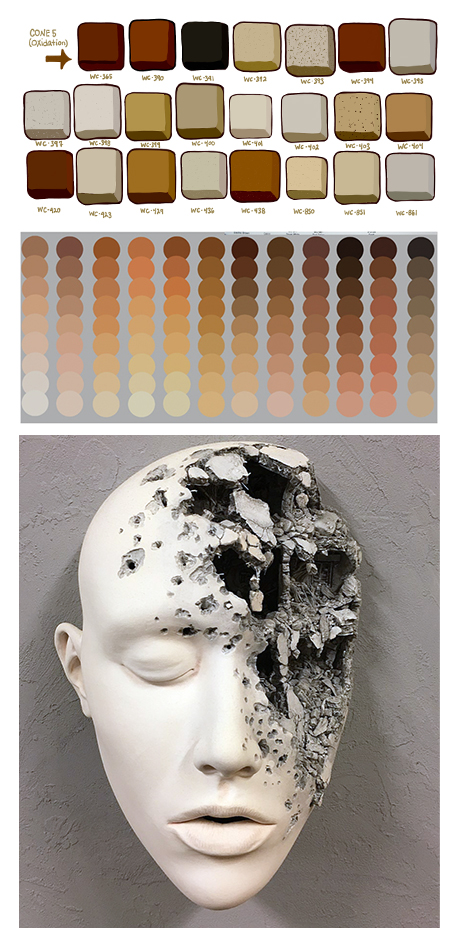

I don’t think anyone here will deny the corollary between clay and skin pigment. The natural colors of clay mirror most skin tones. If you look at stock Laguna clay samples, you can even identify a couple of folks with iron freckles. This isn’t too damning, as clay tones and skin tones are both in the earth-toned category.

I don’t think anyone here will deny the corollary between clay and skin pigment. The natural colors of clay mirror most skin tones. If you look at stock Laguna clay samples, you can even identify a couple of folks with iron freckles. This isn’t too damning, as clay tones and skin tones are both in the earth-toned category.

Similarly, if we prance over to the porcelain side of the spectrum, it’s common knowledge that porcelain has historically been revered for its “skin-like appearance.”i Long before America’s inception and Europe’s fixation on porcelain, it was exclusively produced in East Asia. Dating back to the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.), China was the hegemon of kaolin – the key component in porcelain. When I conceptualize the tactility of porcelain resembling skin, I immediately gravitate toward Johnson Tsang. His work elicits this undoubtable surrealist approach where you can truly feel his work. Whether you’re a fan of Tsang or favor the classics like Michelangelo, potters and sculptors alike have long understood the connection between porcelain and skin. Though less detailed in surface tactility, ball, stoneware, and earthenware can, in fact, make a convincing human sculpture.

Are we to assume a natural material that resembles skin tone and is used to create human sculptures has nothing to do with race? Let’s assume not and proceed down this line of thinking.

Clay and people are fundamentally different. For starters, one is alive, though perhaps it depends on how much of a clay enthusiast you ask. Nonetheless, if we recede to a simplistic approach concerning color, how does color fair in tandem with people and clay? Can race, indicated by color, live on through something as inanimate as clay? In the 1940s it surely lived on through the Clark Doll experiments.

A married couple of psychologists ran a series of experiments to study the psychological effects of segregation on African American (AA) children. While this experiment was intended to study their self-esteem, it has implications of color living through objects. They presented each child with a Black and White doll and proceeded to ask a series of questions along the lines of: Which doll is bad? Which doll is good? Which doll resembles you most? Et cetera. According to Dr. Clark, the testimonies were “disturbing.” Kids would run out of the room, begin crying, or slander the “bad doll” (which was unequivocally the Black doll for an overwhelming majority) whenever the children faced cognitive dissonance.

The experiment’s findings suggested that children made unconscious decisions about the dolls through systematic color associations. As they socially maneuvered through their youth in America, they learned to associate the color black with negative connotations and the color white with positive. The visual color concept of race stifles the American population regardless of whether or not you’re “blind.” Therefore, are we unconsciously upholding these same colorist associations through clay?

Unknowingly, I upheld those colorist associations for probably the first eight years of working in the medium. Perhaps it’s confirmation bias, but I saw myself choosing white clay over brown clay for a long time. One of the main mental breaks I had in California was the cognitive dissonance I had between my AA identity and my socially imbedded Eurocentric identity. The latter, stifles a large percentage of African Americans to this day. On face-value it could seem like choosing porcelain over a terracotta or dark stoneware would prove unrevealing. To most it probably was, but during that time I could find no particular reason for why I craved porcelain for throwing over dark clay bodies. My only explanation when prompted by teachers or friends was that it looked “cool” or was more “difficult” to throw. Following that mental break, I was reaffirmed in my Blackness, and I made conscious decisions to question and excavate those racially organic tendencies.

Artists Adero Willard and Yinka Shonibare make conscious decisions within their artwork, knowing race lives through color. Willard has always viewed the surface of a pot like the skin of a human. She stacks layer upon layer to demonstrate the intricacies of “identity, materiality, history, and design.” Choosing to work in terracotta, she seemingly references the abundance, use, and history of the clay body itself. Similarly, Shonibare replaces the skin of his sculptures with elaborate patterns. Moreover, he removes the heads of his work as they indicate too much of a racial background.

src="/sites/default/files/private/Yinka.png" style="width: 300px; height: 349px;" title="Yinka Shonibare installation titled: Champagne Kids, Bellerby and Company Globe, Photo credit: Peter Bellerby. tinyurl.com/2zah5kny" />

Regardless of one’s heritage, an artist must be aware of color and how it intrinsically implies race, especially within American society. That said, what are the societal implications of race in clay? If there’s a clay hierarchy, are you suggesting porcelain floats atop the summit? I’ll answer these curiosities with a more concerning question.

Aware that race lives though color, what does the commodification of porcelain suggest?

Envision the British Empire as one that has nearly every natural resource on the planet. They span over thirteen million miles, have over fifty colonies, and transported over three million slaves. Each king or queen was gifted with the divine power to rule as if synonymous with Gods. As an empire, what more could you want? Well, imagine coming across a material that aesthetically matched your luscious skin pigment. Not only that, but a material reserved for the elites, used in the arts, was imported, and therefore dubbed exotic. Porcelain was an exemplar of prestige, a reflection of the bourgeoise’s narcissistic taste and a reaffirmation of the divinity, preciousness, and purity of White supremacy; this idealism surged into porcelain’s idée fixe.ii So much so, I’ve found suggestions that Europeans shipped engravings of Christ to China to be painted on the surfaces of porcelain objects.iii

The egoism of the British empire suggested the sun never set on its horizons, and the purity of porcelain pedestalled that same narrative. In other words, through porcelain, Europeans could fall deeper in love with themselves.Porcelain was prized for its elite commodification; Europe’s affiliation with fine china mirrored its colonization. Europe’s co-option of traditional Chinese culture emulated its own unregulated expansion.

No longer did porcelain exist as just a cultural object of China, it was now produced to fulfill European desires. Porcelain fever initiated a commodification of clay, Chinese culture, and Asian Bodies. In Half and both: on color and subject/object tactility, Anna Storti engages with the idea of her Asian identity being a component of objecthood. In doing so, she illuminates the very extent to which her identity is perceived as an object rather than a subject. She frames her exploration through the work of Asian American ceramicist Jennifer Ling Datchuk, who explores the same thematic concepts through porcelain. Through Datchuk’s ceramics, Storti learned that race is not made exclusively on or with skin, but “through the production, trade, and aestheticization of porcelain.”iv

No longer did porcelain exist as just a cultural object of China, it was now produced to fulfill European desires. Porcelain fever initiated a commodification of clay, Chinese culture, and Asian Bodies. In Half and both: on color and subject/object tactility, Anna Storti engages with the idea of her Asian identity being a component of objecthood. In doing so, she illuminates the very extent to which her identity is perceived as an object rather than a subject. She frames her exploration through the work of Asian American ceramicist Jennifer Ling Datchuk, who explores the same thematic concepts through porcelain. Through Datchuk’s ceramics, Storti learned that race is not made exclusively on or with skin, but “through the production, trade, and aestheticization of porcelain.”iv

I, as many of you, have felt like an item through the White gaze. When you feel like an object, it’s synonymous with the reductive quality of being a commodity rather than a human being. When selling my ceramic wares in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the only people buying my work were White. I could count on one hand how many Black folks purchased my work. It makes sense, as the area was predominantly Caucasian. But that said, an ominous feeling remained. Were they buying my work because it was actually good? Were they buying it because I was a nice guy? Or were they buying it because they wanted to save me? Perhaps that’s the enduring trace of selling your identity as an artist. Now, as my wares rest on the shelves of maybe two hundred people, I still can’t seem to distinguish what was purchased: me or the work.

It's the duty of the artist (if they accept any) to implement their identity into their artwork.

Whereas Storti dives into the depths of her Asian American identity, what intrigues me most is her ability to analyze herself through porcelain.

Noted before, porcelain was considered skin-like for its tactility and gentleness. As Storti suggests, the issue isn’t within the technical properties of porcelain, or how it echoes her Asian femininity. The dilemma rests in the commodification of Asian Bodies and porcelain, the latter of which intrinsically creates a hierarchy of clay. She concludes, “There is an enduring trace of difference when race lives on through color.”v Of no one’s fault but higher Eurocentric dominating institutions, the people face and endure objectivity from the utter obsession of the commodifying culture. Racial tension, inadvertently or not, lingers in color, and therefore, clay.

How does the British Empire’s commodification of porcelain lead to a clay hierarchy?

There’s no doubt in my mind some critics will assert porcelain was meant to be bought and cherished. I agree. I believe we live in a world where art should be loved from an emotional perspective. It’s satisfying beauty that someone put their heart, time, and soul into should be witnessed by all parties that it emotionally resonates with. It’s certainly one of the main reasons I like to create. Despite this reasoning, I also believe there’s a thin line between infatuation and love, or more specifically, between obsession and adoration.

In 618 CE the Tang Dynasty catalyzed the international influence of porcelain. Tea consumption and exchange of materials on the silk road made the demand for porcelain skyrocket.vi Despite this increased popularity, it was almost one thousand years before “porcelain fever” broke out in the seventeenth century when, “more than three million” pieces of porcelain were exported to Europe.vii Native to China, porcelain came to be known as “fine china” in lieu of other replications coming into circulation.viii Regardless of new porcelains, fine china remained paramount.

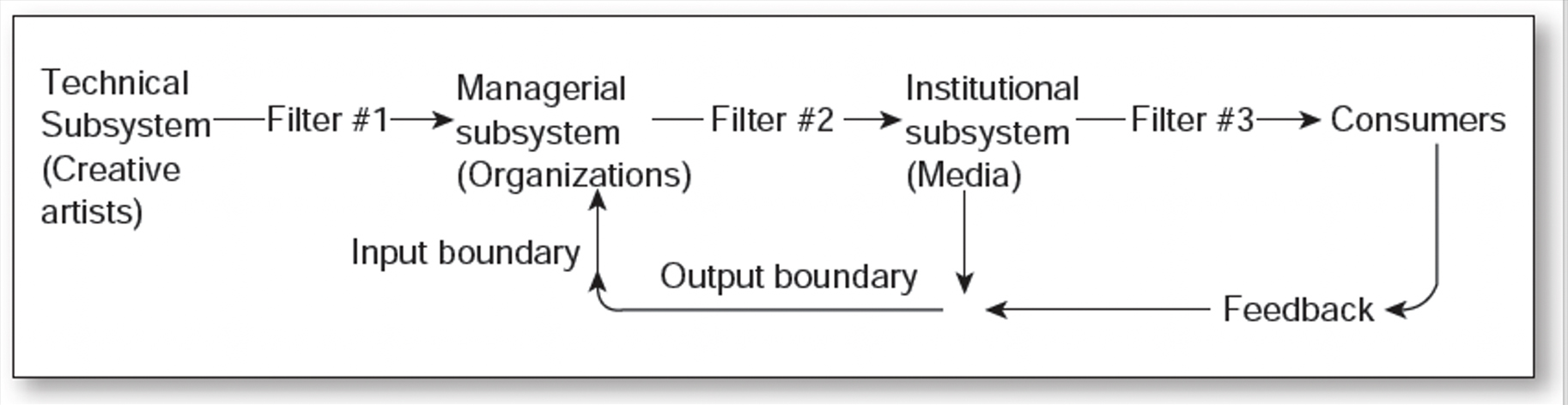

When elitists admire a cultural object, sometimes the general population will explore its use. However, when elitists obsess over a cultural object, there is a trickle-down effect on the general population that consumes standardized culture. That effect causes everyone to want the same item. The culture industry system contextualizes this phenomenon by demonstrating how ideas, products, and mechanisms evolve and are adopted through society.

In 1972, sociologist Paul M. Hirsch developed a useful model outlining the relationship between systems and consumers of pop culture.ix In Processing Fads and Fashions: An Organization-Set Analysis of Cultural Industry Systems Hirsch states:

The concept of an industry system is proposed as a useful frame of reference in which to (1) trace the flow of new products and ideas as they are filtered at each level or organization, and (2) examine relations among organizations.x

The culture industry system examines how pop culture creates standardized products, which create standardized people.xi Within this framework, whatever dominating forces supersede the systems and institutions that, to varying extents, control society. In doing so, these systems and people create a “set of falsified beliefs [or] consciousness” that constricts and manages the common person who consumes the prevalent culture.xii Stemming from Marxist theory, the Frankfurt School conceived culture industry as a mechanism to stress the “antidemocratic nature

of popular culture.”xiiiHence, although people falsely think western democracy places citizens’ agency above the governments, this autonomy never rested with the people to begin with. Likewise, culture is stringently facilitated by the higher institutions that dominate and has minimal input from consumers. Capitalism built on the backs of Black people illustrates this very cruel nature. The same dilemma is mirrored in the commodification of fine china.

You may be asking yourself, “Isn’t the culture industry system only relevant for today?” Indeed. It didn’t exist during porcelain fever. Nevertheless, the mass-production model that existed as America’s foundation was never dismantled, so it unnoticeably crept in and made a home without any regulation from consumers.

In other words, we never questioned the implications of elitists commodifying fine china, so its obsession became widespread without rebuke. This is one of many systems we never addressed, because we took them as absolute – or allowed them to persist. Even though we have creative artists, media, and consumer feedback now, as a society, we never backtracked the indoctrination of White supremacy on its people. We just kept moving forward. Thus, subtle mechanisms continue to promote Whiteness, and the government refuses to acknowledge the underpinnings of the status quo, allowing the problem to cascade through virtually every facet of American life.

I dare not suggest a specific moment that a clay hierarchy began. It was a culmination of porcelain fever, the commodification of fine china, the psychology of color attached to race, society’s inherent reluctance to question indoctrination, and lastly, the rhetoric surrounding color and the history of clay. Therefore:

How do we talk about clay?

During my college days, I had the pleasure of taking a critical rhetoric course. In doing so, I came to realize Aristotle was dubbed “the father of rhetoric.” His famous persuasive techniques: ethos, pathos, and locos were among his many contributions to the field. In conducting my own research, I was made aware that his persuasive techniques closely alluded to the story of Enheduanna and the Book of Ptahhotep. The former was a woman from the Middle East while, the latter was written by Egyptians. Both of whom predated Aristotle by a millennium. This course opened the flood gates to questioning who writes our history, why they write the history they do, and most importantly, from what perspective is that person writing from. Is it Afrocentric or Eurocentric?

There’s a shortage of ceramic critical writers but, more crucially, there’s an absence of people of color and the Queer community. Of the roughly one-hundred-forty-two stories published in Studio Potter since 2020, “about thirty-two percent were written by non-White and/or non-Cisgendered people.”xiv If most folks writing and documenting ceramic history are innately writing from a Eurocentric context, how is that conducive to the holistic understanding of the ceramic field, let alone any other? Ceramics dates to at least 24,000 BCE, yet we still lack the fundamental necessary representation. If everything we are reading is filtered through a White lens, how can we see anything else besides that tint?

Granted, as every continent has a ceramics history, there are certainly BIPOC critical ceramic writers. However, as an American society in tandem with the culture industry system, who dominates the ceramic writing, magazines, galleries, and museums?

If you don’t come from an oppressed minority, it takes time, awareness, education, empathy, patience, experience, and a swath of mistakes to even begin to partially understand what that minority goes through. (I’ve made my fair share of mistakes with Black feminism.) That said, blissful ignorance is sadly still an option. Nonetheless, especially as artists (a group of people meant to shift the forefront of culture) is the ignorance of our writing and art simply perpetuating White supremacy? It shouldn’t have taken two decades, and a pre-dominantly White college, of all places, to inform me Aristotle potentially plagiarized from women and Black people. I’m aware that’s the ongoing trend of America given the supreme court outlawing lynching two-hundred and fifty years after the fact. But what are we doing about it, and is it enough?

Closing thoughts

Feel free to disagree, agree, argue, or walk on anything I’ve said – hell, I’m only twenty-two. To ask anything of you is selfish, but I leave you with this: Empirically, ask any non-potter or ceramicist to name the types of clay they know (as I’ve done personally at least a hundred times to see if I could make this assertion), and they’ll likely be unable to do so. If they can name a clay, they’ll probably say porcelain first. Some might be able to name terracotta. (I assume because they’ve dabbled in gardening.) Perhaps it could be a coincidence, but if you find, like I did, that the majority name porcelain first – does that indicate anything to you?

That said, I’m not concerned with wicked White tendencies anymore. As stated before, White supremacist mechanisms underscore most American institutions and systems. As one Black potter, I can’t undo millenniums of White supremacy. Why would we take the time, effort, and patience to unshackle the clay hierarchy? I, as do most ceramicists from marginalized communities, move forward understanding there is a hierarchy of clay bodies that is starkly reminiscent of racialization in America.

Dante Hayes speaks to the greater African diaspora informed by traditional African heirlooms. Roberto Lugo places Black faces on pots – a place they aren’t typically represented in American pottery. Mapo Kinnord’s work is inspired by the artwork of West Africa. In doing so, she elicits an “ancestral memory.” As a speck of hope, our work aims at decolonizing an art form that should have always remained intimate and unscathed by European inadequacies.

What other pervasive mechanisms are we allowing to linger in ceramics that uphold White supremacy with our inept indolence?

Author's Note: I’d like to give a special thanks to Jill Foote-Hutton, Adero Willard, Meghen Jones, William Street, and Oliver Shaw for their tireless mentorship, edits, and discussion surrounding these topics. Without their help, these findings wouldn’t be possible.

Endnotes:

i Gavin. (2021, August 23). Chinese Porcelain History from the 1st Century to the 20th. Chinahighlights. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/culture/porcelain-history.htm

ii Gal, S. (2017). "Qualia as value and knowledge: Histories of European porcelain." Signs and Society, 5(S1). https://doi.org/10.1086/690108

iii Tiliakos, N. (n.d.). The "Porcelain Road” — 16th and 17th Century Trade Routes by Sea. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.igavelauctions.com/blog-posts/the-porcelain-road-16th-and-17...

iv Storti, A. M. (2020). "Half and both: On color and subject/object tactility." Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory, 30(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770x.2020.1791383

v ibid

vi ibid

vii ibid

id="_edn8">viii Christy P, C. (n.d.). History of Fine China. classroom.synonym.com. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://classroom.synonym.com/

ix Griswold, Wendy. 2013. Cultures and Societies in a Changing World. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

x ibid, 2013: 657.

xi Adorno, Theodor W. and J. M. Bernstein. 2020. “Culture Industry Reconsidered.” The Culture Industry 98–106.

xii Adorno, Theodor W. and J. M. Bernstein. 2020. “Culture Industry Reconsidered.” The Culture Industry 98–106. (Griswold, 2013: 657).

xiii Griswold, 2013: 31

xiv Co-editor Jill Foote-Hutton contributed this count during the editing process.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor W. and J. M. Bernstein. 2020. “Culture Industry Reconsidered.” The Culture Industry 98–106.

Allison - La Marketer - Gran Luchito. (2022, March 23). The 10 best restaurants in Mexico. Gran Luchito. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://gran.luchito.com/restaurants/mexicos-best-restaurants/

Boston, G. (2021, October 26). Want to eat less? Change the color of your plate. The Washington Post. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2014/03/21/want-to...

Gavin. (2021, August 23). Chinese Porcelain History from the 1st Century to the 20th. Chinahighlights. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/culture/porcelain-history.htm

Griswold, Wendy. 2013. Cultures and Societies in a Changing World. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

kopinadmin, P. (2019, July 24). Here's the reason why the colour of your dinner plate matters. Kopin. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://kopintableware.com/article/heres-the-reason-why-the-colour-of-yo...

Carolina. (2017, December 15). Carolina. Gracious Style Blog. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.graciousstyle.com/wpblogs/where-can-i-get-the-dinnerware-use...

Fortin, J. (2020, February 26)."Congress moves to make lynching a federal crime after 120 years of failure." The New York Times. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/26/us/politics/anti-lynching-bill.html

Gal, S. (2017). "Qualia as value and knowledge: Histories of European porcelain." Signs and Society, 5(S1). https://doi.org/10.1086/690108

Gannett Satellite Information Network. (2019, August 22). "The 30 best restaurants in America." USA Today. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.usatoday.com/picture-gallery/life/2019/04/24/30-best-restaur...

History of Chinese porcelain in America and Europe. Boston Tea Party Ships. (2020, February 20). Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/tea-blog/history-of-chinese-porcelain...

Hughes, L. (2010). The Negro artist and the Racial Mountain (1926). African American Studies Center. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.78675

Home. Porcelain Manufacturers & Suppliers, China porcelain Manufacturers Price- page 2. (n.d.). Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.made-in-china.com/manufacturers/porcealin_2.html

Kogel, J. E. (2014). "Mining and processing kaolin." Elements, 10(3), 189–193. https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.10.3.189

M.Admin, & M.Admin. (2020, December 23). Difference between Bone China, fine China, and porcelain. KnowledgeNuts. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://knowledgenuts.com/difference-between-bone-china-fine-china-and-p...

Miller-Wilson, K. (n.d.). Stoneware vs. porcelain: Key differences in Dinnerware. LoveToKnow. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://antiques.lovetoknow.com/antique-glass-china/stoneware-vs-porcela...

Schroeder, P. A., & Erickson, G. (2014). "Kaolin: From ancient porcelains to nanocomposites." Elements, 10(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.10.3.177

Storti, A. M. (2020). "Half and both: On color and subject/object tactility." Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory, 30(1), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770x.2020.1791383

Tiliakos, N. (n.d.). The "Porcelain Road” — 16th and 17th Century Trade Routes by Sea. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.igavelauctions.com/blog-posts/the-porcelain-road-16th-and-17...

Toki. (2021, August 11). The Beauty & Diversity of Japanese pottery. TOKI. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.toki.tokyo/blogt/2017/6/13/japanese-ceramics

"Top exterior paint colors of 2021." Shoreline Painting. (2021, April 8). Retrieved August 29, 2022, from https://shorelinepaintingct.com/blog/most-popular-home-exterior-paint-co....

Tsoumas, J. (2021). "Traditional Japanese pottery and its influence on the American mid 20th Century ceramic art." Matèria. Revista Internacional D'Art, (18-19), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1344/materia2021.18-19.6

Wolfgat. (n.d.). Wolfgat. wolfgat. Retrieved June 3, 2022, from https://www.wolfgat.co.za/