Citizen Potter

Citizen potter: A potter who is an active participant of a community, be it geographic, ceramic, or online, and who is seeking social change based on passions and convictions.

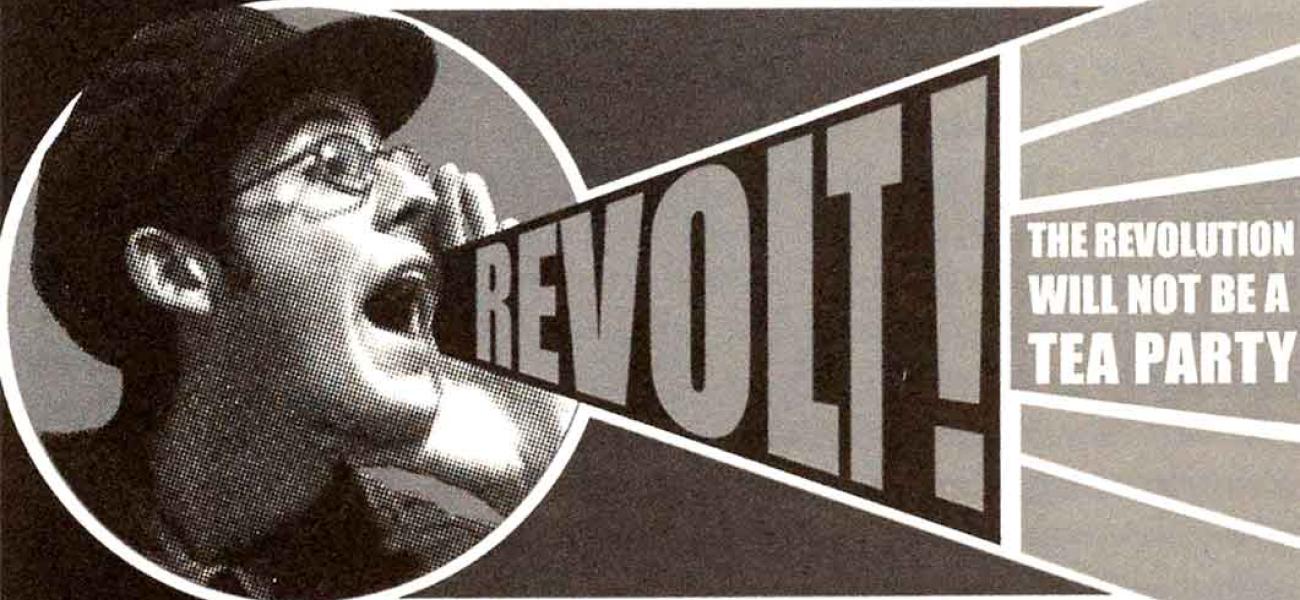

Ten years ago, Garth Johnson – then a grad student at Alfred University – made a propaganda-style sticker of himself shouting into a bullhorn, "Revolt! Pottery Liberation Front! The revolution will not be a tea party!" One of these stickers has been a touchstone for me since then, unstuck to any fixed object and coveted by many While Garth's message had more to do with pushing ceramics past a crusty mingei aesthetic, I saw it as a call to arms for handmade pots. The sticker catalyzed a major shift in my thinking; I realized how effective pop culture and grassroots activism could be in advancing the cause of handmade pots and expanding our audience for crafts. The sticker itself was compelling because it was funny, graphically beautiful, and unexpected. It struck me that making functional pots is a closed-loop system – that making is inseparable from using, and that if we could only get the word out, more people would love and use pots. Pots in use become reminders of human connections and even facilitators for relationships. Stickers like Garth's help bolster the idea of pots as objects that can ignite social change.

As my studio practice has become more established, I find myself increasingly drawn out into the community; to mobilize and reach out. I see that beneath my desire to make good pots is a desire to make connections, and to create community among people through pots. Like Garth, I recognize that how I get the word out is a creative act, and as fundamental as the actual making of a cup or bowl. For me, this engagement comes in the form of concrete projects, as well as an ongoing campaign to advance the ideal of handmade pottery.

Beyond an affinity for the material, many of us choose to become potters because we feel it is meaningful work. What we make is both a product of the human creative process and a useful commodity. On a day-to-day basis, people are affected by looking at or using our work. One hundred and fifty years after William Morris, we are still struggling with the politics of making objects by hand in a capitalist and global society that, by and large, undervalues skilled hands and slowness in making work. In popular culture, the object of choice is the cheapest or trendiest one, and handmade objects represent just a fraction of what is produced and consumed in the larger culture. When consumers buy the handmade, they make a choice to support and promote small, independent businesses and a life dedicated to exploring art. Through the DIY movement's effort to politicize consumerism with campaigns like the Buy Handmade pledge, buyers are not only reminded of just how political their choices are, but are also better equipped to act on these convictions because of the mobilization than can take place quickly online.

There are many ways to be citizen potters. Making by hand is in itself a political choice; then there is the content of what we make and how we choose to engage our communities. There is also the question of how we disseminate our work, as well as how we support advocacy in our own community through such organizations as Potters for Peace and the Craft Emergency Relief Fund. My own civic engagement has taken many forms, including the Obamaware project, local Empty Bowls events, and serving as a board member of the Archie Bray Foundation. Advancing handmade ceramics – by broadening our audience and changing the perception of functional pots as an out-moded and uninteresting art form – is not civic engagement in the traditional sense, but it is an integral part of my studio practice and an ongoing mission. When we are successful at creating an indelible link, either experiential or perceptual, between pottery and a quality of experience, we touch people in some fundamental way. Potters are dedicated to focusing on objects used for food, a material infinitely rich in personal, cultural, and historical meaning beyond its obvious function as physical nourishment. Americans spend a good third of their non-sleeping, non-working hours preparing food and eating. More than any other craft medium, making pots positions us perfectly for integrating ourselves into the quotidian, exploring and emphasizing the social role of pots as creators of habit (good or bad) and objects of comfort.

Fundamental to my studio practice are all the auxiliary objects normally thought of as marketing tools, such as postcards, t-shirts, and a web site. I use them to underscore the intersection of art and everyday life, and to invite people to care about the pot and the experience it creates. In my early twenties I worked for several years as a freelance photojournalist in Seattle, gaining access to the reality of other people's lives that I normally never would have seen. I learned to think on my feet aesthetically and to crop quickly in the camera, rather than fuss in the darkroom. This experience and my photo-based aesthetic served me well in the year and a half I spent translating ceramics into the interactive digital medium of the web.

When I launched my website in 2002, I included a page called "Pots in Action,'' a collection of candid and posed pictures of my pottery taken by users. This is an unmediated forum; there is no art direction from me and people's images range widely, from kids and pets to cups on bathroom sinks or taken on vacation. The popularity of this community project illustrates the cultural value of pots in our lives, and reminds us of the independent lives pots take on apart from their makers. The photographs are yet another level of direct contact between me and the user, but here it's the user creating the content and the message.

Annual postcards are another way I show pots in a new light. I have consciously avoided the straightforward "profile shot" of a pot on a gradated background. An irate squirrel has his meal interrupted; a woman licks her plate clean in order to show it off; a cowboy winks over a steaming cup of coffee. These images are hip, catchy, and populist, showing pots in the context of function rather than as art relegated to a shelf. It has been said that the arts of our times are found not in museums but in blockbuster movies and advertising. My newly made video takes the familiar pottery demonstration to a new level by exploiting its entertainment value. Humor, good music, and showing an unusual technique link studio pottery to popular culture, and make it accessible to an expanding audience.

Making the connection between art and everyday life also means exploring alternatives to the gallery in regards to showing and selling pots. Alleghany Meadows' Artstream Nomadic Gallery, a silver trailer-cum-gallery-on-wheels, takes pottery straight to the streets, and presents pots the way they might be seen in a galley kitchen. The Artstream's most recent project is a "lending library" of pots, based on the exchange of some artwork or narrative by the borrower for use of the pot. Bartering is another kind of engagement we practice naturally within our respective communities; those for whom handmade pottery might be out of reach can afford it on their own terms. Much of my time at the Women's Studio Workshop five years ago was spent organizing its version of Empty Bowls, the grassroots fundraiser that happens all over the country, in which soup is served in handmade pots that are then purchased by participants. And collaborations between advocates of the Slow Food movement, chefs, and potters are cropping up left and right, at events and collaborations such as Down to Earth in West Chester, Pennsylvania, the Union Project in Pittsburgh, and Tei Tei restaurant in Dallas, where pots by Peter Beasecker's students at SMU are being used. These efforts to move art out of the gallery benefit us all.

Social networking tools such as Facebook have made connecting to a new audience even easier, by reaching out through degrees of separation to those who, though a mostly non-ceramic crowd, care enough for their friends to read about their interests. Because Facebook works best among friends who are trusted tastemakers, content that

is truly interesting has a decent chance of going viral, because these users tend to accumulate more "friends,'' put more energy into keeping their content fresh, and have their hands in many different kinds of communities. As public as Facebook is, ideas do get bounced around in real time, in a way that only a few years ago was impossibly tedious.

With our predilection for fostering community, it is a natural step for potters to become informed citizens and activists, especially now, when the cultural zeitgeist asks us to be engaged on all levels – local, national, and international. Between the resurgence of the green movement and the inspirational, grassroots campaign of Barack Obama, many of us have thought deeply about our values and have done what we can to contribute to the causes we care about. In October of 2008, I organized Obamaware, a fundraiser for Barack Obama's presidential campaign that involved twenty-seven ceramic artists and a decorative arts historian, Sarah Archer, who wrote an essay contextualizing our efforts in historical political pottery. The kernel of the idea came to me just before Arrowmont's Utilitarian Clay Conference in September, and by the end of the three-day event it had grown into a reality because of the strength of the ceramics community

The factors for success were already in place; I had contacts in ceramics, a great web designer, an information technologist, Photoshop and Dreamweaver skills of my own, and a sizable mailing list. The invited artists took up the cause with enthusiasm, many dropping other projects, and in a month had finished their Obama-themed work. Traffic on my web site shot up 1,700 percent the first day the web page was launched, then hovered at 500 percent for months afterward. Obamaware went viral with write-ups in more than seventy blogs raising the visibility of handmade ceramics, most noticeably with non-ceramic audiences, and illustrating to many outside the field just how powerful it could be to mix politics and craft. Over the course of a three-day auction, we raised $10,483 for the Obama campaign. It was grassroots fundraising and civic engagement at its best, because it was a joint effort between artists and buyers.

In a survey taken just after the auction, many people noted that their perception of ceramics had changed because of the overtly political stand these pots took. While there is no question that this was the right event at the right time, it was revolutionary as a craft fundraiser because of its speed, low overhead, and viral nature. The artists raised money by doing what they do best, and the buyers participated in a more meaningful way than a straight monetary contribution would have accomplished. Obamaware was an opportunity for all of us to invest in something together. It was a physical manifestation of the grassroots change that so many Americans wanted so deeply.

Because of Obamaware, I realized that sometimes it is not enough to just follow my own particular quirks and desires in the studio. Occasionally a foray into realms outside our own interests is the most energizing thing for our art. This year I'm collaborating with two different artists. Sara Varon, a Brooklynbased illustrator, and I will be working on a show of dinosaur pottery at Red Lodge Clay Center in Montana, and in September of 2009 "Who Lives in Greenwich Village?" – a tile and platter installation made with Andy Brayman – will open at Greenwich House Pottery in New York. The content is provided by the Manhatta Project; working out of the Bronx Zoo and the Wildlife Conservation Society, the Project aims to raise ecological awareness, especially among New Yorkers, by showing the interconnectedness of all the species and ecosystems that still exist to varying degrees in the area. This year, 2009, marks both the quadricentennial of Henry Hudson's "discovery" of Manhattan and the centennial of Greenwich House's founding as a settlement house dedicated to helping immigrants find their footing.

Our hope for this show is that besides being visually gorgeous, it will broaden the ceramic audience and be informative for the residents of Greenwich Village and the Pottery. Three maps will be layered: an ecological map from 1609, a street map of Greenwich Village from 1909, and a map of animals that roamed the area in 1609 (several of which are now endangered in the Northeast, including the cottontail rabbit and the mountain lion). By focusing on the area, we hope to tap into the local residents' sense of pride, ownership, and curiosity about their own community, and celebrate both Greenwich House as a cultural landmark and the existing ecosystems in danger just outside the city. As an added incentive to support conservation efforts, Andy and I are donating five percent of our proceeds to the Wildlife Conservation Society. We are both working outside our usual range, yet the opportunity to form a relationship with the Mannahatta Project has given deeper meaning to our collaborative work, a very satisfying feeling indeed.

Civic engagement and potters' studio practices are natural bedfellows. What has been a traditional partnership is now, through new media and the Internet, more capable than ever of bringing about positive change on micro and macro levels. As a field, we have much to feel hopeful about, and I see nothing stopping us as we embrace our ideals and bring them to bear on our lives as citizen potters. As then-director Josh DeWeese used to say when I was a young potter at the Bray, "All ships in the harbor rise with the tide."