Cheap to Make. Fun to Spray.

We were at Don Hutchinson’s studio for three years before we fired his soda kiln. That sounds like a long time – and it is – but really those years passed quickly. When we signed the lease with the developer who'd bought Don's Surrey property after he retired, the little collective we’d formed while still in art school was all about cone 6 and earthenware. We were electric fire. We were playing off industry. We slipcast. We’d been taught by the people who were sick to death of hearing about Leach. I could barely throw.

We were at Don Hutchinson’s studio for three years before we fired his soda kiln. That sounds like a long time – and it is – but really those years passed quickly. When we signed the lease with the developer who'd bought Don's Surrey property after he retired, the little collective we’d formed while still in art school was all about cone 6 and earthenware. We were electric fire. We were playing off industry. We slipcast. We’d been taught by the people who were sick to death of hearing about Leach. I could barely throw.

Don would come by and say, shame that people nowadays don’t make their own glazes, and I would say indignantly that yes we do, look at these recipes; look at all my frits – and Don said what he meant was going to the mountains and hauling down granite and crushing it up in a (homemade) ball mill and putting it in a high-fire gas kiln and you can get some pretty good glazes that way. I nodded, thinking how I didn’t even drive and that at the moment ceramics seemed punishing enough without needing to break rocks.

Collective member Sam Knopp always wanted to fire the soda kiln and she knew the most out of any of us about how to do it, but it was going to be a big job. Don said – I thought they’d tear it down so I stopped cleaning it up. Don said – I sold most of the good kiln furniture. We pulled the car out on its rusty tracks, and inside were listing bagwalls and a frightening stack of mismatched posts and shelves glued together by glass and rat debris. The bottom layer was foaming silicon carbide, a lunar landscape as unknown to me as the real thing.

The inside walls looked like tempura. The door bowed and the arch sagged. Both kilns were beautiful assemblages of once-new brick, salvaged brick, cars and tracks from the defunct Crane toilet factory. We always talked ourselves out of it, or said – if we get another lease. Every six months we signed another. Sam moved to Alberta and set up her own studio and we still hadn’t got the kiln going. I was scared of the gas cost and burning things down and the mess and mostly, dumbly, had no imagination for how to translate the work I was used to making into high fire.

In the summer of 2018 I visited clay pals Tony Wilson and Kristine Aguilar at the Shadbolt Arts Centre in Burnaby for the last days of their residencies. The kiln came up again. Tony would help, he said, and Kristine was keen too. To every excuse and worry I offered, they shrugged. I went home and started sorting shelves. Angela Hopkins and Heather Lippold, collective members still working in the studio, joined in. We set a date in November for the first firing to bring the kiln out of retirement.

This process felt like a different kind of learning than in art school. I phoned Don to invite/plead with him to join us but there was no answer. In his absence it became a sort of archaeology; guessing from the shapes and marks left behind how the kiln fired, what was needed, how he'd operated. We bought high-fire clay. We repaired the bagwalls, and we tidied the door. We carefully chipped the stack apart. We heard that Don was sick.

We bought a masonry cup for the angle grinder, cleaned the shelves. I phoned again and left a message. We trimmed the cedar tree that had overgrown the chimney. An email to Don was unanswered. We acquired a kiln god; a stoic pink rabbit whose black-glazed eyes had run in a community centre glaze firing, dripping gothic tears. Its maker, horrified, threw it away. Angela, the centre’s tech, knew it would be perfect and rescued it to perch atop the arch next to Don’s terracotta figure. We mixed a palette of cone 10 glazes and slips and we bought a little pesticide pump for the critical spraying of soda ash. Slowly the right shapes assembled – the correct cones and rings and wads. On a Saturday we loaded our first firing.

That night Heather and I stayed up watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer in the studio. We tried to light a burner to candle the load overnight, but in the wind and lacking a safety it promptly went out, feeding gas invisibly into the kiln. At midnight we gave up. The firing log documents the next morning’s struggle: 4:30 a.m., 5, 5:30, 6 – burner out, relit, out, relit, and about a twenty-degree climb in temperature. The sun came up and the wind died and finally steam rose off the kiln for the first time in at least five years, maybe more.

When cone 010 bent mid-day, we tightened the dampers and lit all six burners and the kiln slipped into reduction easily. Bright flame leaked through gaps in the worn brick and the light inside went murky. These things weren’t familiar then in the way they’ve become. Tony, the most experienced in firing and a great teacher, pointed out the signposts as we went. When we asked what to do he always said first – it’s your firing, what do you want to do? Or we’d speculate about what Don would have done, had done. Are kilns machines, or tools, or places? Firing a kiln feels like going to visit a certain place – one that temporarily appears, a glowing castle in the air, and disappears as the bricks cool. Were we visiting the same place Don went, or making a new one?

The numbers on the pyrometer climbed. We adjusted the gas and the dampers and bricks. The pressure grew and flame started to leak through the roof. Linda Doherty came by, studied the kiln, offered gentle suggestions. She’d driven a long way. I just love kilns, she said. Pink Goth Bunny the kiln god acquired a fine layer of soot.

My boyfriend Liam is not a potter, but for ten years he’s had a front-row seat. He says things like – You’re a maniac and all your friends are too. He’d been watching this newest pottery problem from a safe distance but now stepped forward. Did we want to use his air compressor, he asked, to try and blow-dart the soda in? Sure, we said, and while he wrestled the compressor out we hunted for a suitable blow-dart tube.

My boyfriend Liam is not a potter, but for ten years he’s had a front-row seat. He says things like – You’re a maniac and all your friends are too. He’d been watching this newest pottery problem from a safe distance but now stepped forward. Did we want to use his air compressor, he asked, to try and blow-dart the soda in? Sure, we said, and while he wrestled the compressor out we hunted for a suitable blow-dart tube.

The first lesson learned was that if you hold a length of drainpipe up to a brick-size opening in a reducing kiln with lots of backpressure, you create a tunnel of oxygen-starved fire and flame will leap out the other end at your face. The blackened drainpipe was traded for a rusty steel pipe which we used once then quit, fearful of blasting bits of rust all over our pots. Liam stepped forward with another idea. The others tried to stall the kiln while he and I drove to the hardware store and headed to the plumbing section.

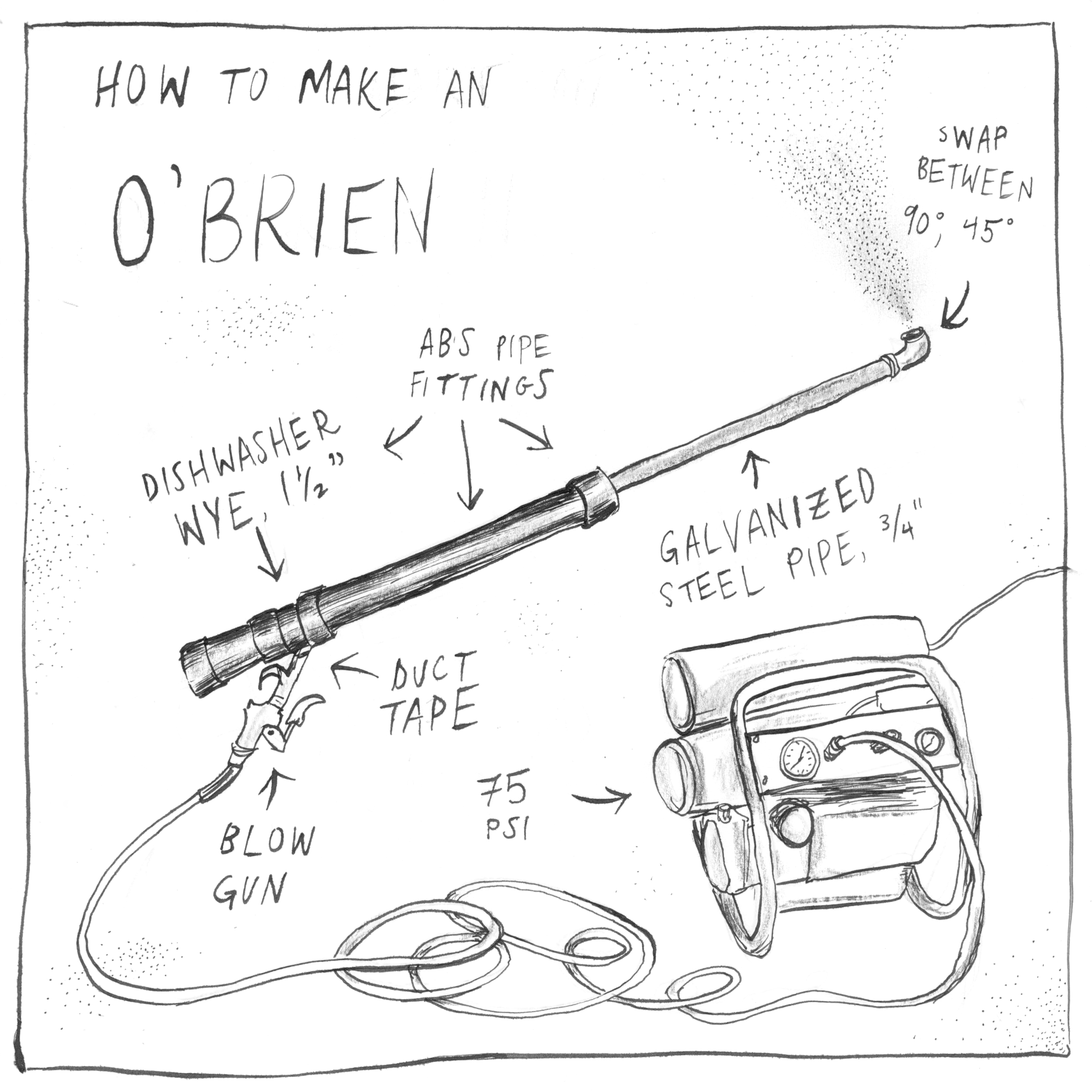

Liam had no experience with soda firing but became a potato cannon expert in early adolescence. He selected a galvanized steel pipe, a 90° elbow, and a jumble of plastic tubes and fittings to connect with the air compressor nozzle. He assembled a modified potato-cannon, hooked it up to the air, and we delivered the last few doses of soda ash. The draw rings were glossy, dark, and spattered with soda. Cone 10 was soft in the front and back, and at 8:45 pm we shut down.

The results, unloaded a week later, were surprising and beautiful. I now know that we were exceedingly lucky for a first firing. The surfaces were sublime. The reduction atmosphere made the porcelains icy grey and the red clays rich, Martian. The soda made glassy visitations to each piece. I’d worried the firing would change my drawings and it had – they were smudged, erased, glowing, and much better. The pots had visited the other place and come back as changelings. There were enough mistakes and missteps and good things to keep going forever.

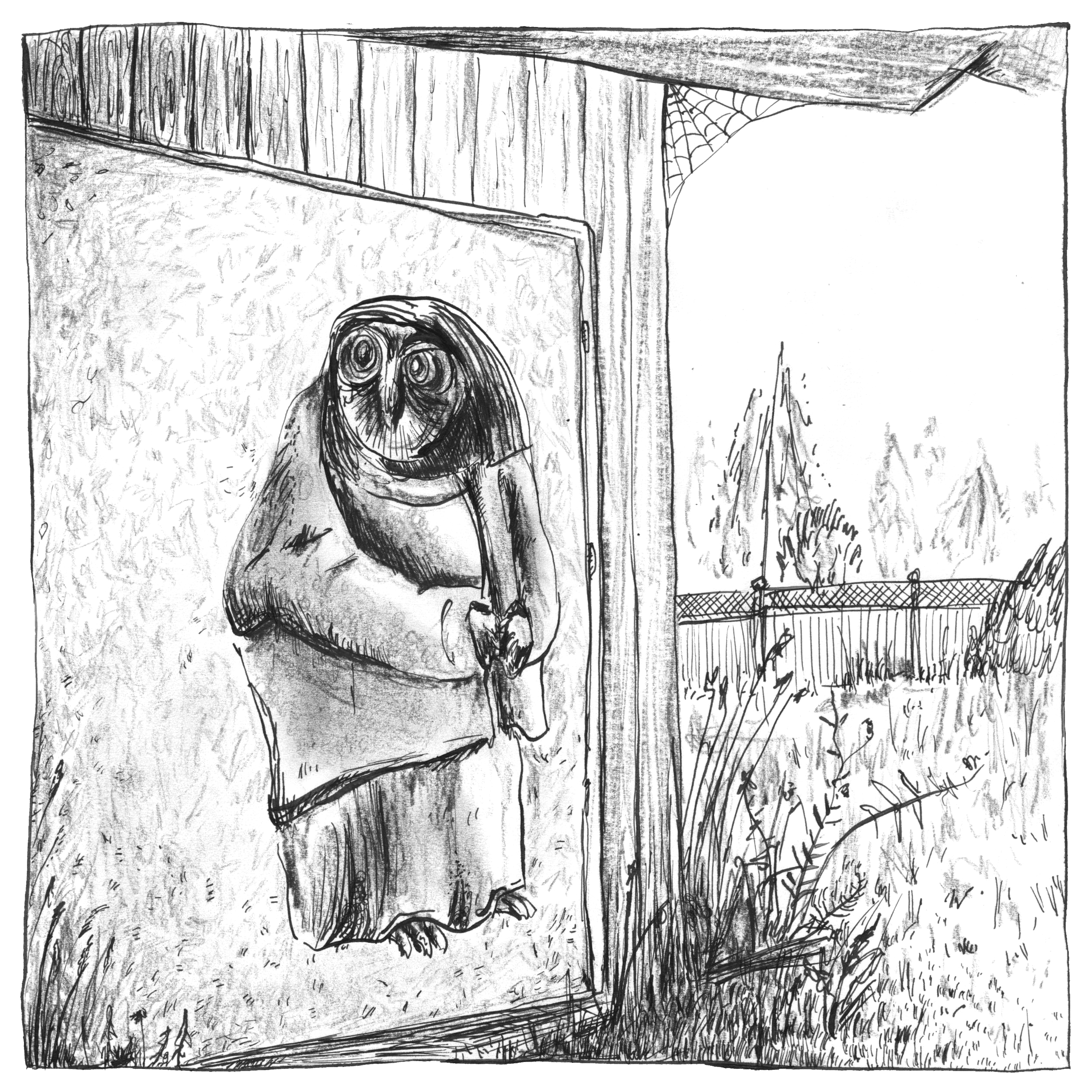

Three days after that unloading we got word that Don had died. A huge community of students, friends and artists grieved. I regretted more than ever that we had waited so long to fire and that I wasn’t ready before to ask him about breaking rocks. At the studio we wheat pasted a blown-up image of his sculptural self-portrait, an owlish figure called The Professor, on a wall that faces the soda kiln. We’ve done many firings since then. Don is a teacher in absentia. The Professor watches us and we guess – how did he do this bit?

Three days after that unloading we got word that Don had died. A huge community of students, friends and artists grieved. I regretted more than ever that we had waited so long to fire and that I wasn’t ready before to ask him about breaking rocks. At the studio we wheat pasted a blown-up image of his sculptural self-portrait, an owlish figure called The Professor, on a wall that faces the soda kiln. We’ve done many firings since then. Don is a teacher in absentia. The Professor watches us and we guess – how did he do this bit?

Every firing since we’ve used the soda gun that was improvised from

the first firing’s problems, modified a little as we go along. Kristine calls it microdosing, since you can so accurately measure the amount of soda that goes in each port. Or we call the soda gun the O’Brien, after Liam, which he doesn’t approve of. A friend pointed out that O’Brien is the engineer on later episodes of Star Trek who quickly fixes things to save the ship, so let’s agree it’s actually named for him. The dry soda spray gives unique results – spattered, glittery, lots of variation and visual texture, and easily distributed throughout a load with varied ends on the gun. With this method lots of soda travels into the upper atmosphere of the stack. Do you want to use an O’Brien? Please try it. It’s cheap to make. It’s fun to spray. Tell us how it is for you and if you make improvements. It’s a team sport, rah rah. It gives everyone something to do: one person to pull the brick, one person to spray, one to load the next shot, two vampires to vamp the dampers in and out. We’re O’Brien evangelists.

The studio has expanded beyond the original collective and our firing crew has grown. There are critical people who are part of the crew now who weren’t at the first firing but, when I remember, it’s impossible to not see them there. We’ve done all the tasks of preparing, firing, and cleaning up over and over and over again, shared meals and traded pots and built snow sculptures while we waited for cones to bend. For over a year now we’ve met and fired with masks on.

Atmospheric firing is a pretty rarified pursuit. Sometimes I feel like I’ve acquired a jousting habit. Sure the horses eat a lot and the lances are heavy, but we’re knights aren’t we? Kilns like these are tied to land access and the resources to hook up gas or source wood, and the time to manage it all. I can’t imagine any other scenario where a crew of non-homeowners, working our many assorted jobs, could fire as often and as cheaply and with as much freedom to experiment.

After six years here, the developer has served us notice to leave so he can demolish the property – the house where Liam and I live, the studio Don built, the kilns. We’ll salvage bricks from the kilns if we can but we don’t have land to rebuild them on. Finding new studio space and even somewhere to live is a serious challenge in one of the most unaffordable housing and rental markets in the world. This place means everything to me, but even I can see that its value to us is dwarfed by the absurd monetary value of the property. The proposed building will offer more housing which the community desperately needs.

We have our souvenirs from visits to the temporary place – pots, an invented technology, a sturdy crew, gratitude. The pressure builds. We’ll come up with something.

Illustrations by Amelia Butcher