An Abiding Interest in History

My Foundations

I have an abiding interest in the history of ceramics and in particular, the vessel. Much of my work in recent years has been at least partially based in the study of historical vessels, with a focus on form and the language of form, by which I mean the ways in which form embodies idea, evokes emotion, reinforces cultural identity, or expresses narrative. I see vessels as being essentially formal and abstract. At the same time, they may fulfill a practical or metaphoric function.

THE MODERNIST SERIES, my most recent body of work before embarking on the Italian Series, consists of sculptural representations of utilitarian forms arranged on, and framed by, large stoneware trays. The forms are largely based on European, Modernist-era silver sets for tea, coffee, and chocolate. My interest is in the abstraction and repetition of forms and visual motifs, and in the still-life-esque arrangement of these forms. However, I am also interested in the loaded nature of these forms. They carry references to the classism of the societies in which these forms were developed, signifying status and worldliness, as the drinking of tea, coffee, and chocolate developed from trade with and colonization of Asia and the New World. The materials from which they were made (porcelain and silver) were also intended to convey the status of their owners. Historically, these forms were elaborately ornamented and adorned with formal language and imagery that reinforced these ideas. Most of these signifiers have been deliberately erased in their modern manifestations as the rituals of their use have become less practiced. My work is also quite formalist, and the actual function of this ware is vestigial. Unlike my historical inspirations, in my Modernist pieces I place a deliberate emphasis on process and substance. The forms are pinched up from moist clay and the glazes are chosen and applied to emphasize their substance and character. The forms are left unrefined and retain the repetitive marks of the pinching process. The glazes are thick and have rich visual texture. The dark, coarse stoneware trays are left unglazed. These sets are oversized to emphasize their weight and physical presence.

Academia

As an academic, my work is episodic, meaning that I have short, focused periods between semesters in which I can work in the studio. I am also required to think and write about my work in the form of reports and assessments on a regular basis. I do have the freedom to make what feeds my curiosity, without thought for the salability of my work. Rather, universities reward research in the form of publication and exhibitions. The driving force behind my work is curiosity. I seek to learn through making. Each new body of work is a way for me to get my head around something I do not fully understand, rather than being an expression of my personal identity. The result of all of this is that I tend to work in series, organized around a particular idea.

I have taught the history of ceramics for about two decades, first at the University of Minnesota – Minneapolis, and now at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln (UNL). My first classes were primarily lecture-based. Students would write papers and take exams, but each would also make a historical reproduction as part of their research. In the summer of 2008, Julia Galloway invited me to team-teach a summer course at Novia Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax, Canada (NSCAD), entitled MAKING HISTORY. She had a vision of creating an exhibition in which the audience could walk through the history of ceramics. For this class, she and I both lectured, but we also gave demonstrations of historical techniques. The primary activity of students was making and glazing, and, of course, putting together the exhibition. Artists learn best through making, and Galloway, who designed the course, knew this instinctively. Many of my students have said that they feel a special relationship to the person who originally made the object that they are recreating. They gain an insight into the object and the maker that they would not have gained were they simply reading and writing about it. The course created much engagement and excitement among the students.

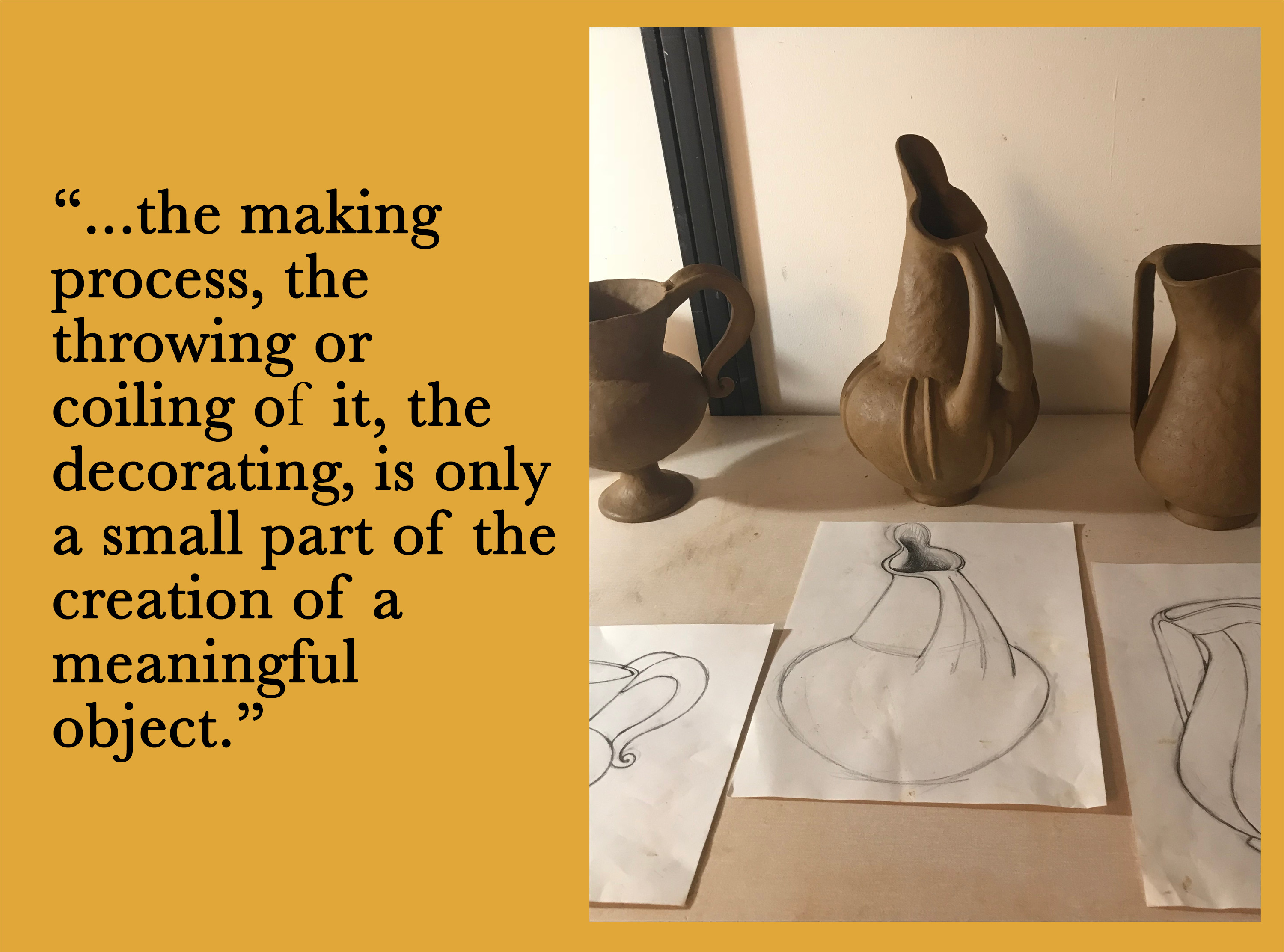

My current history classes at UNL are modeled on that first class we taught in Nova Scotia. Students in this class begin by choosing a series of pieces they will reproduce. As they make, they research the piece, learning about process and material, but also about the cultures and rituals within which the pieces were made and used. In this way, they learn about the broader meaning of function. A key reason I continue to teach history in this way is that it reinforces the concept that idea is at the core of made objects. The forms and surfaces that they are recreating and studying were defined by the core beliefs and daily lives of the people who made and used them. They also learn, I hope, that it is a lot easier to make an object that has already been fully conceptualized; that actually, the making process, the throwing or coiling of it, the decorating, is only a small part of the creation of a meaningful object. Organizing an exhibition is also a key part of this course. The students must discuss the various relationships between the wide group of objects they have created, and then decide how to demonstrate these relationships through the organization of the exhibition.

Sabbatical Project

In 2018, for the first time in my twenty-five-year teaching career, I became eligible for a faculty development leave (a.k.a. sabbatical). Universities often provide financial support for research travel and, when considering what exactly I would do with this opportunity, I immediately thought of Italy. Thirty years ago I spent a semester abroad in Italy as an undergraduate student at Rhode Island School of Design, which had a huge impact on my development as a maker. To return there was a way to revisit some of my earliest inspirations, namely the ancient and historical art, architecture, and decorative objects of the Italian peninsula.

I decided to focus on a study of ceramics particular to this region. Four types of ceramics came to mind as fitting this description: Etruscan ceramics, terra sigillata from Arretium (now Arezzo) made during the first century CE, Italian majolica, and Medici porcelain from the Renaissance period. While visiting museums in Italy and London, I discovered another type of ware produced in Apulia, located in the southeast of Italy, during the same time as the Etruscan civilization.

History

A little history lesson for those readers who may be unfamiliar with these types of ware…

the Roman Empire. They lived in the center region of Italy, now known as Tuscany. The stages of Etruscan civilization loosely coincide with the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods of Greek art. Often unpainted, the ceramics made by the Etruscans were influenced by Greek ceramics and sculpture, but had an exuberant and quirky character that was unique to their own culture. The Etruscans created elaborate graves and necropolises where a huge array of ceramic vessels have been found, some of which were unique to the Etruscans, while some were made in loose imitation of Greek wares. Objects made of coarse clay are often called impasto. Bucchero ware is a particular type of Etruscan ceramics that was highly polished and fired in reduction, making it black.

The terra-sigillata-type of ceramic ware, was developed in Arretium and is also known as Arretine ware. It was primarily made in molds and coated in (you guessed it) terra sigillata – a fine, semi-vitreous, bright-red, iron-rich slip, unique to that region.

Italian majolica is probably the best-known type of ceramics from Italy. Created during the Italian Renaissance, it began with simple, wheel-thrown forms, decorated in copper green and manganese brown-purple on an opaque, shiny, white glazed surface made with lead and tin. This early ware is often called majolica rustica or majolica antica. Majolica is of course known because of its elaborately painted surfaces. Majolica painters eventually developed a wide range of colors and could replicate the most elaborate Renaissance paintings on the surface of vessels. I chose to focus on a study of the forms of the vessels, rather than the painted surfaces.

My intention was to travel to Italy to see as many of these objects as I could in person, to photograph them, do a series of drawings, and then to make vessels based on these forms with the goal of creating still-life groupings of vessels. I was fortunate enough to be given a residency at LA MERIDIANA International School of Ceramics in Tuscany. I was there for a month and interspersed trips to museums with work in the studio. La Meridiana is idyllic – situated in the countryside outside of a town called Certaldo, it is about an hour from Florence by train. The artist-in-residence is given a cottage of their own with a kitchen, bedroom, and studio. The cottage is across a small courtyard from the main building, a seventeenth-century farmhouse, surrounded by olive orchards and grape arbors. The main studio is extremely well-equipped and well-run.

After leaving the residency at La Meridiana, I then traveled to Rome and London to visit and research ceramic museum collections. Later, I did a second month-long residency at RED LODGE CLAY CENTER in Montana to continue my studio work.

My Creative Contributions

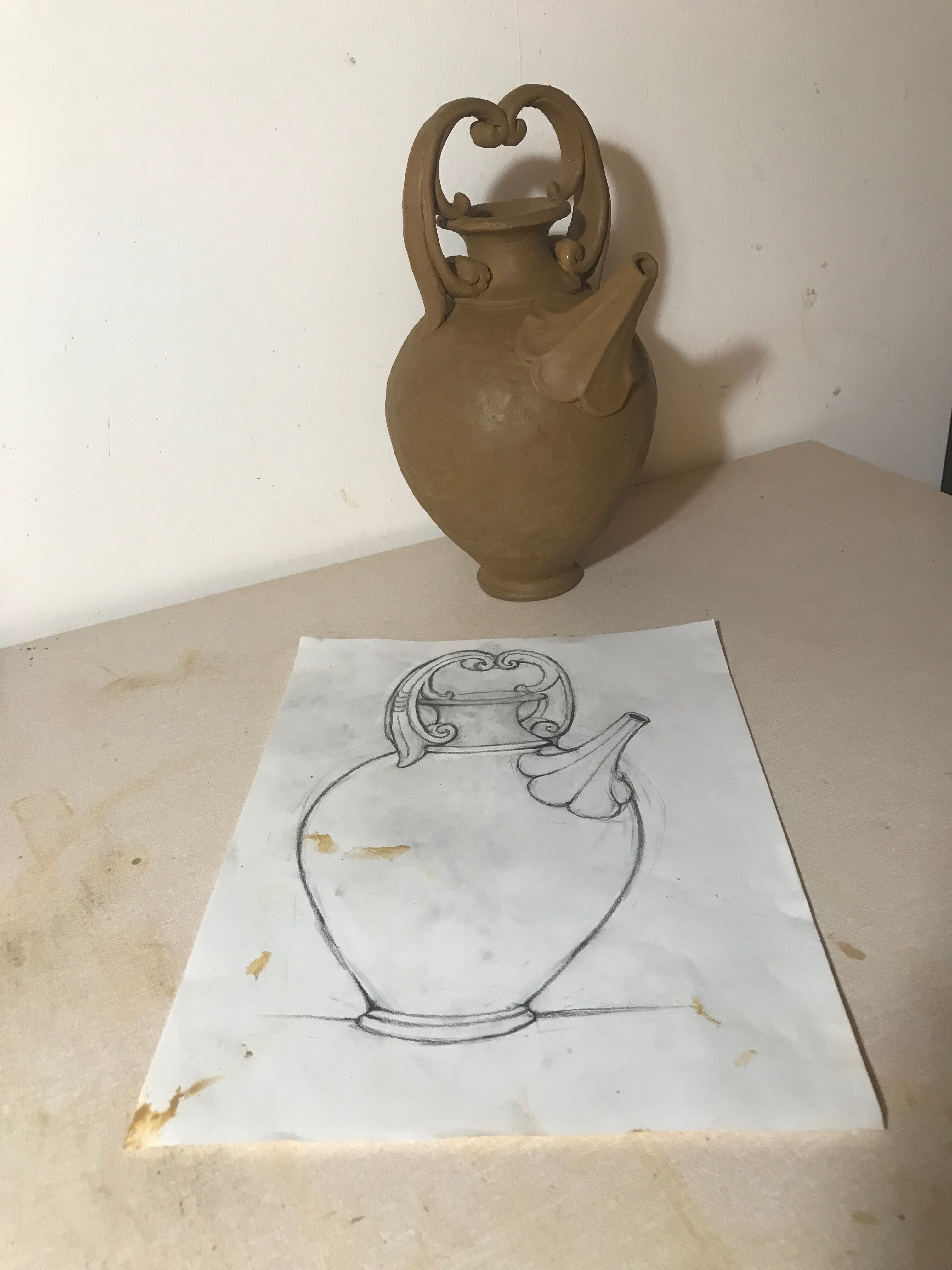

The continual quandary for my sabbatical project has been, “What exactly is going to be my creative contribution?” At La Meridiana, I made drawings from my own photographs as well as some from other international collections that I found online. I focused on Etruscan objects, majolica, and Medici porcelain. I began by simply making drawings of a selection of the objects I had seen based on a feeling of affinity or curiosity. At first, I was thinking of these as prototypes that I would ultimately transform in some way, creating a body of work that was my own. I found myself more interested in the ancient objects themselves, perhaps because many of them were new to me. There seemed to have been a greater freedom for the makers to explore variations in form during the developmental stages of a civilization. The forms were less codified, less formally resolved, and therefore more mysterious and exciting to me. I am endlessly fascinated by their variations of volume, feet, handles, spouts, and other weird attachments. These engage my imagination and curiosity about their use and their meaning.

Later, when I arrived at Red Lodge, where I was given a huge, well-equipped space and a month of nearly complete solitude in which to sort out my ideas about the direction I wanted to take this project, I began to categorize my collections of images. This led me to focus solely on the Etruscan and Apulian forms for which I felt the greatest affinity and curiosity. I began to see formal relationships and to curate the pieces I was making. All of the museum displays I had seen, containing shelves and cases of vessels, loomed large in my memory. Although each object is curious and interesting, my excitement came also from the array of objects assembled together in each display. These memories also informed my choice of objects and arrangement.

The creative contributions I have chosen to make reflect my personal concerns as a maker. Essentially, the project was a study of historical forms. And I found, after having spent considerable time looking and drawing and making, that I wanted to continue simply reproducing these forms – remaining faithful to their character and proportions. My choice of materials and my building process define my contribution, but also my choices about which pieces to reproduce. The surfaces I have created and the way I have curated and arranged them in relation to one another also reflect my voice.

Process and Product

All of the pieces in this series are coil-built, although the originals were primarily wheel-thrown. I am more comfortable hand-building, and, for me, coiling these pieces is a bit more like drawing in clay, or, in some way, creating a sculpture of a vessel. It involves a slow analysis of the object while I am in the process of physically describing it. The pieces I have made vary in refinement; some of them are sketchier, quickly made and rougher, while maintaining attention to proportion and scale, others are smoother and more refined.

At La Meridiana I used a local earthenware clay body that was formulated by the studio manager, Franco Rampi. It is a beautiful orange color and has a coarse texture. I have done my best to create a similar body here at home that I have continued to use. The color is a reference to the Etruscan tomb ware I am most interested in, which was made in an iron-rich earthenware clay and left unglazed. I have two types of black stoneware that I have been using, both from Laguna Clay, one coarse and the other smooth. Although these are bodies that I have been using for some time, the black color provides a reference to the Etruscan bucchero ware.

In the last two years I have completed three large groupings of objects that I am calling “Etruscan Still Life,” “Apulian Still Life,” and “Bucchero Still Life.” Each consists of about fifteen to twenty vessels. The groupings are curated, not around any particular historic or cultural rules, but for a particular set of aesthetic criteria of my own devising. In some cases I have altered the scale of the objects or modified them slightly in form, while staying in character with the original objects to reinforce the relationships within each grouping. The Etruscan grouping is bare clay, both red and black. Many of the pieces are ornamented with raised clay decoration. Some are pierced. The other two groupings are made of black clay and patterned with a textured white glaze. The glazed patterns are of my own invention and are based on my understanding of the underlying architecture of the forms, as well as reflecting my interest in Modernist-era formalist abstraction.

I have begun to see and develop a relationship between the work I made in the Modernist series and these Italian groupings, primarily through my use of surface. I am reminded that many of the Arts and Crafts and Modernist designers and makers looked to ancient objects for inspiration. Hans Coper’s study of Cycladic art is an example, or Christopher Dresser’s study of Peruvian and Egyptian vessels.

Acknowledgement and Moving Forward

My travel and residencies were funded by generous support in the form of grants from the UNL Research Council and by the UNL College of Fine and Performing Arts Hixson-Lied Endowment.

During my sabbatical I spent days and days in museums looking and photographing and have amassed a huge library of images. Although my focus was Italian ceramics, of course, I saw so much more. The hundreds of other objects I saw and photographed will be used in my history of ceramics class, and as inspiration for future work of my own. I haven’t yet clearly formulated the next direction my work will take, but this catalog of images and the reproductions I have already made of Medici porcelain and majolica ware present possibilities for new directions.

Editor's Note: If you are interested in visiting Italy to pick up an in-person view of history, join Bohls at La Meridiana early next summer for her WORKSHOP from May 23 – June 6, 2021. In this intensive workshop, you will explore ancient pottery forms of Italy and transform historical inspiration into your own, personal expression. Through targeted field trips and concentrated studio time, you will achieve new methods of work and an insight into Italian culture that will inform your studio practice for a long time after the workshop.

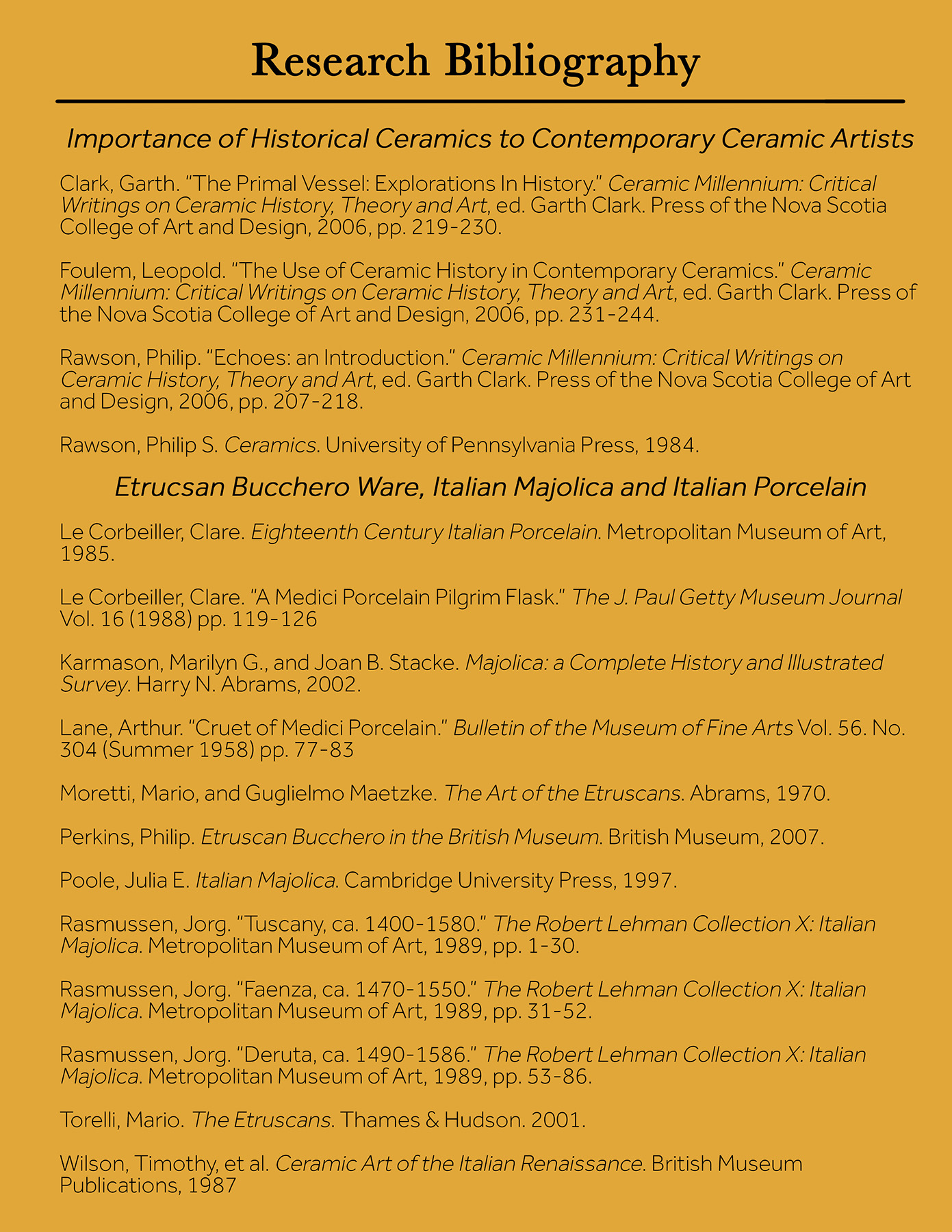

End Notes

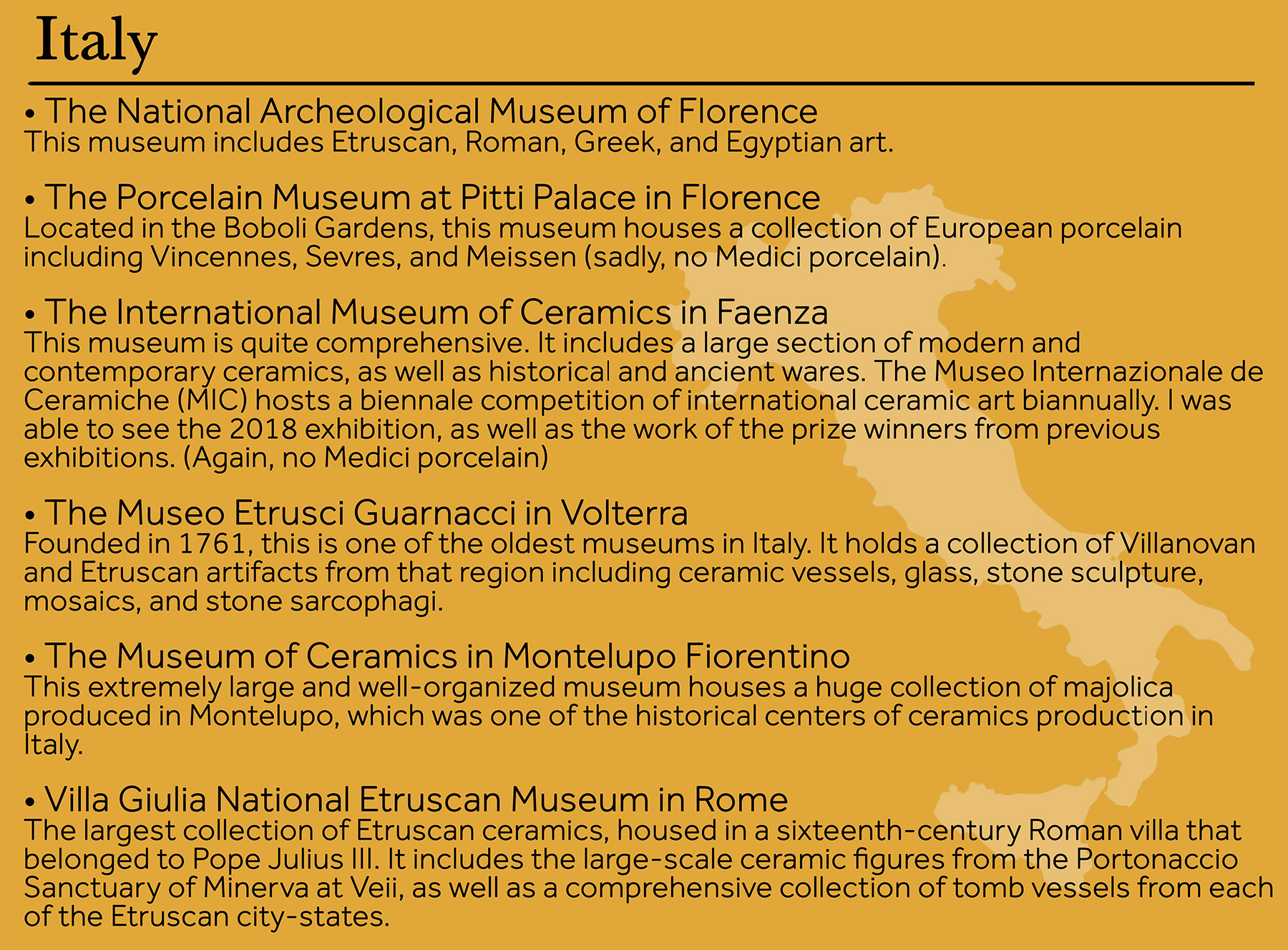

1. Links to Italian Museum sites: The International Museum of Ceramics in Faenza, Villa Giulia National Etruscan Museum in Rome

2. Le Corbeiller, Claire, 1985, p. 5.

3. Links to British Museum sites: The Victoria and Albert Museum, The British Museum, The Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford