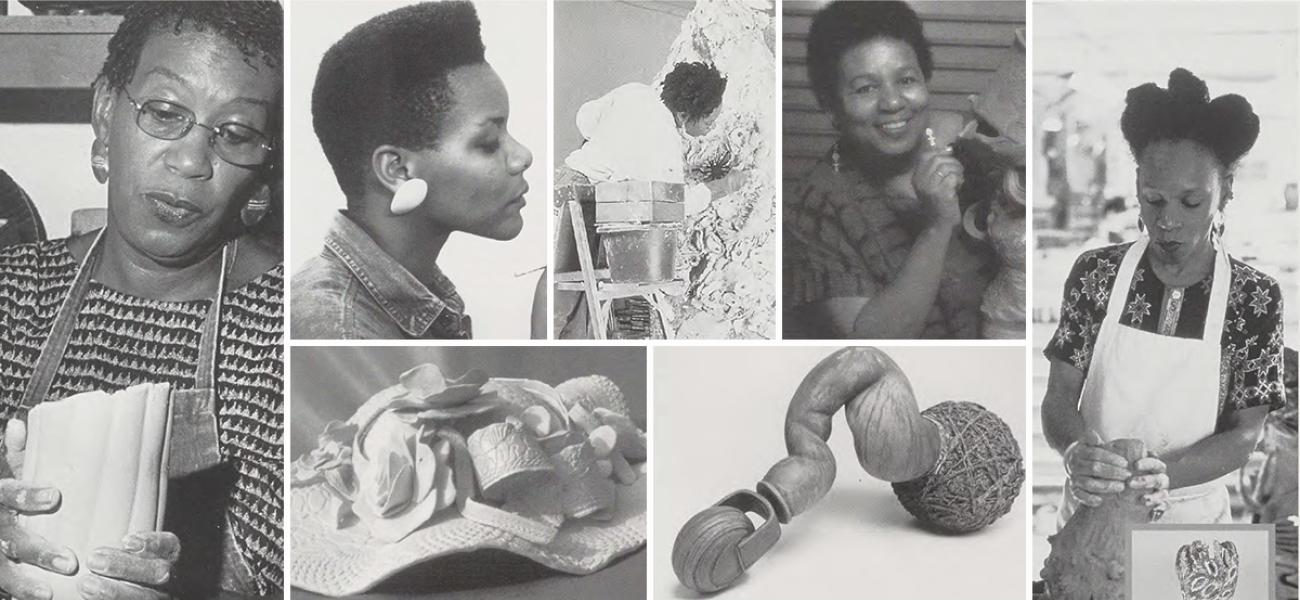

Work and Lives - Seven Ceramic Artists

From the Studio Potter archives: North Carolina Potters - Vol. 26 No. 1, p. 40-47.

We asked Winnie Owens-Hart to recommend several ceramic artists to accompany her forgoing interview "Inside the Pink House – A Conversation with Winnie Owens-Hart." She chose the following seven ceramic artists: Martha Jackson-Jarvis, Sana Musasama, Yvonne Edwards-Tucker, Janathel Shaw, Syd Carpenter, Teresa A. Williams, and Barbara Madden-Swain.

From them, we requested responses to several questions: Was there someone or something that turned you toward clay? How did you arrive at your particular style? Do you have aesthetic threads in common with other ceramic artists? What does your presence in the field mean to you? What makes you stay in the field when statistics and tide flow are against the odds? Here is their work and what they wrote.

Seven Ceramic Artists

Martha Jackson-Jarvis

My artistic style developed from my curiosity and need to seek out a path of survival for a little colored girl from Lynchburg, Virginia. I learned early in my Iife from my grandfather and grandmother the value of hard work and the unquantifiable joy that creeps into your life in the process of making things. From playing in the mud and red clay of Virginia to the University campus, my trek was always toward clay as a life's work.

My artistic style developed from my curiosity and need to seek out a path of survival for a little colored girl from Lynchburg, Virginia. I learned early in my Iife from my grandfather and grandmother the value of hard work and the unquantifiable joy that creeps into your life in the process of making things. From playing in the mud and red clay of Virginia to the University campus, my trek was always toward clay as a life's work.

Ironically, I came to clay as a way of surviving against the odds. The odds, however, were far greater than issues of acceptance in art. I viewed clay as a far more powerful tool with the ability to speak to issues of identity and give voice to my needs. It was a way of laying down the truth and raising up my vision and rhythms of this life. After more than twenty years, I believe these ideas remain essential, and I pursue them vigorously each day in the studio.

The position of working against the flow is a unique vantage point of inquiry and one that I find intriguing. It is clear to me that I remain in the field out of necessity and live with the dictum that "there is still more to say," the narrative that continues to thread and meander its way through the years of work. In a hostile climate, the voice may be shrill and sometimes hoarse, but never, ever, should it shrink and go away.

The most vital thread I have with other ceramics artists is Ceramic History. While I am not interested in drawing frivolous look-alike connections with other ceramic artists, we are inextricably linked in the vortex of history. It is the extensiveness of ceramic history which spans centuries and document fragments of various cultures. Ceramic history provides a glimpse of our humanity and signals that anything in clay is possible.

I view my presence in the field as an important one. The thing that resonates most about my work and point of view is "no limits." In a field and medium that demands tradition and limits, my work seeks other possibilities. I have had to invent the realm where I create, not solely ceramics, not solely sculpture, not solely painting. For the decade of the eighties, that realm was best-called installation work. Most installation work, however, was not about the object and was constructed of temporary materials. In contrast, my work focused on the object as a central power force within the created environment, using very permanent materials such as clay, cement, metal, and wood. Though the category of installation no longer applies, the nature of the materials propelled my work into largescale public commissions. Public commissions allow for the expansion of studio and enable me to employ other artists, which is good, but public commissions come with extensive limitations and should not be viewed as a panacea. My present work seeks to capture the energy of the installations, the power of the single object, and the scale and magnitude of public work and channel it, without creative limits, into garden environments.

I view my presence in the field as an important one. The thing that resonates most about my work and point of view is "no limits." In a field and medium that demands tradition and limits, my work seeks other possibilities. I have had to invent the realm where I create, not solely ceramics, not solely sculpture, not solely painting. For the decade of the eighties, that realm was best-called installation work. Most installation work, however, was not about the object and was constructed of temporary materials. In contrast, my work focused on the object as a central power force within the created environment, using very permanent materials such as clay, cement, metal, and wood. Though the category of installation no longer applies, the nature of the materials propelled my work into largescale public commissions. Public commissions allow for the expansion of studio and enable me to employ other artists, which is good, but public commissions come with extensive limitations and should not be viewed as a panacea. My present work seeks to capture the energy of the installations, the power of the single object, and the scale and magnitude of public work and channel it, without creative limits, into garden environments.

Yes, I am clearly in the field whether the field is ready to expand the boundaries or not. In the fullness of time when all those young historians will need dissertation topics one day, Martha JacksonJarvis, Late Twentieth-Century Ceramic Artist, sounds good!

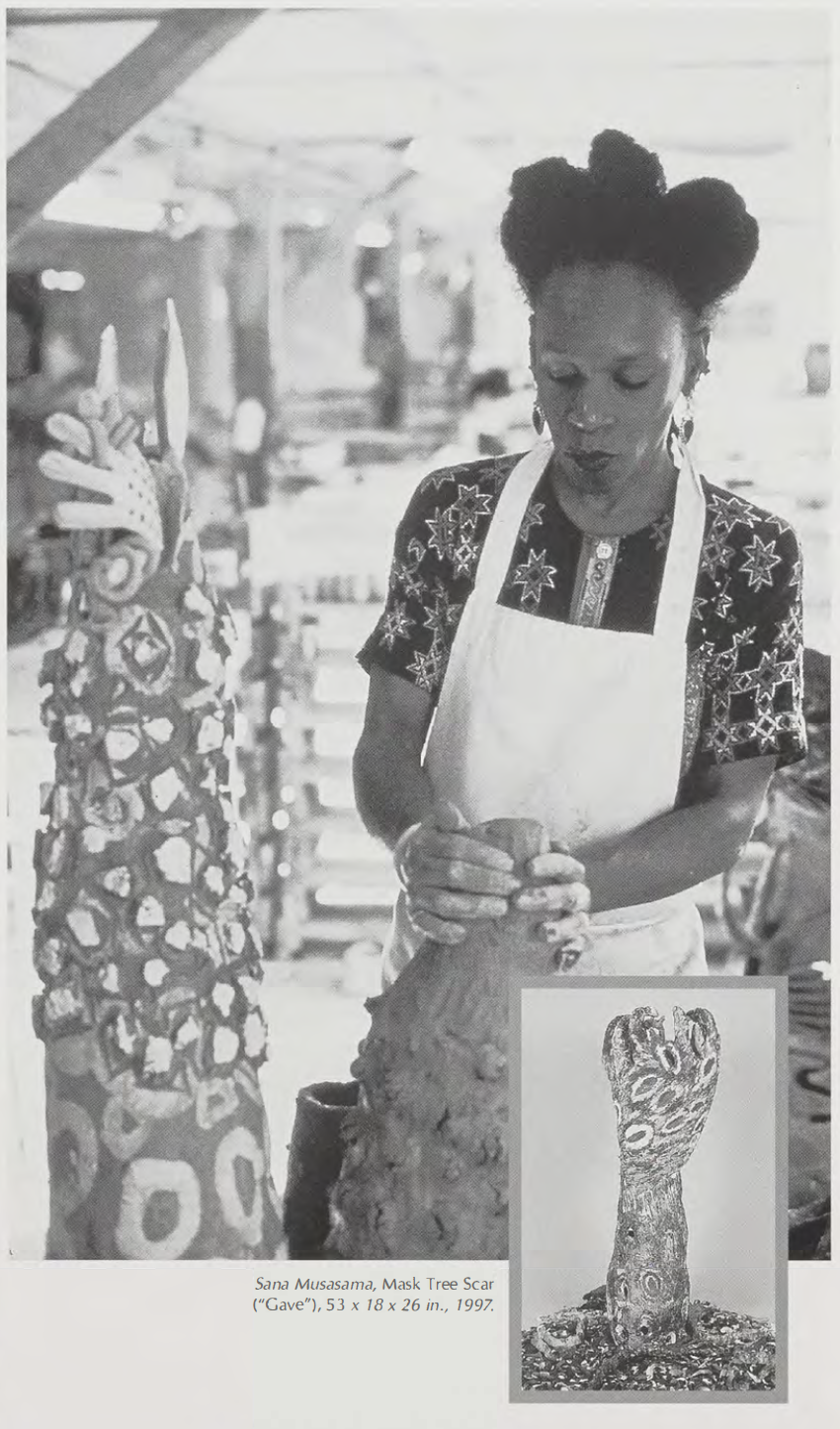

Sana Musasama

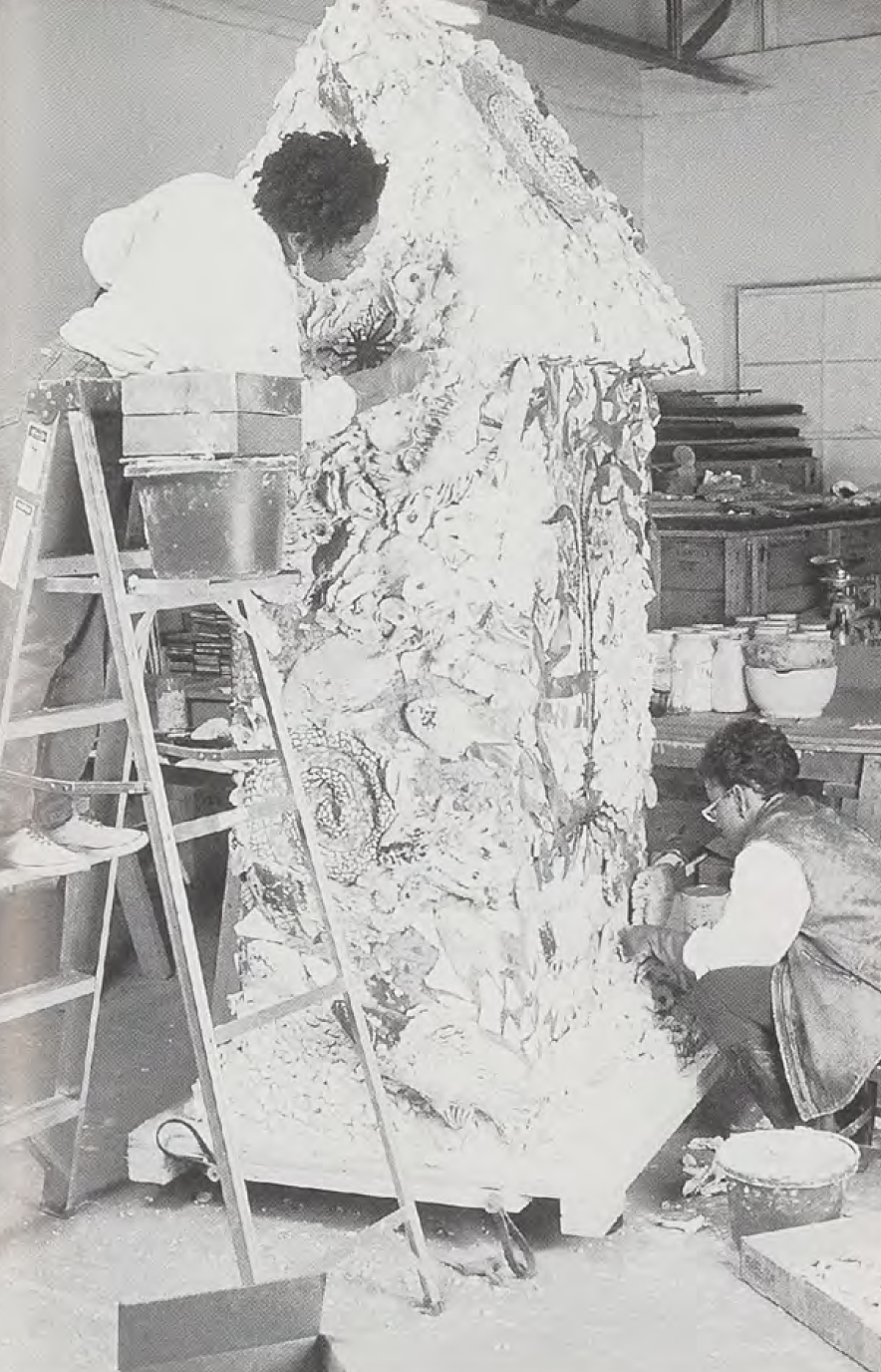

As a sculptor, I work in ceramics. I use both clay and glaze in non-traditional ways. My work is the interpretation of personal narratives and historic events, focusing on themes of time, place, and gender. My work is inspired principally by my travels and further informed by my reading of autobiographies, travel journals, and world history.

Ranging in scale from five-and-a-half to twelve feet, my sculptures are abstractions full of metaphors and hidden images. I mix and integrate various clay bodies, such as Egyptian paste and porcelain, and utilize unique firing atmospheres and temperatures.

My current work is inspired by the reading of early Abolitionist movements in our country's history. I was deeply moved by the story of the Maple Tree Movement that existed in the 1790s, a movement embraced by three races -the Native Americans, the Dutch, and the indentured African servants. I decided to devote my creative energy to reinterpreting this history in the form of ceramic sculpture. I began this body of work in 1991 and still feel imbued with passion and power to continue pushing my clay to retell our collective story.

Yvonne Edwards-Tucker

I think that clay found ME – quietly, viscerally, and subconsciously rather than my choosing IT! In my conscious mind, I was quite comfortable making sculpture from mixed media and found objects, and drawing under the tutelage of Charles White (an internationally renowned African American artist) and Joseph Mugnaini at Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles, from 1965-68.

When I was a child, my mama and cousin Lena had encouraged my penchant for writing and illustrating my own stories by surrounding my god-brother and me with crayons, pencils, paint, scissors, old magazines, paper, and play-dough. So that, years later, I aspired to learn more about painting and sculpture in wood, marble, and metal but not clay.

Back in the midwest in the early 1960s, I was actually frustrated with clay. My instructor at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana practically ignored me, so I didn't connect to clay at all then. Years later, in Los Angeles, I saw the works of Peter Voulkos' students and other potters involved in the "West Coast Clay Revolution" in storefront windows, art festivals, and local galleries and museums. I responded to something about the quirky shapes of the goblets, jars, and funk sculptures, as well as to the work of the Wildenhains and Natzlers. Soon I found myself meandering over into the ceramics lab at Otis. Helen Watson introduced me to Danish throwing techniques, Chinese celadon and tenmmoku stoneware glazes, and Japanese raku ware.

As soon as the clay started taking over my life, I started practically living there most nights, after painting and printmaking classes were over. Bob Glover and Mike Frimkess, a former student of Voulkos, were also working there in the evenings, and a friend who later became my husband and art-partner, Curtis Tucker, also joined us (at first to see where I was so late at night, but he too caught the clay bug and became a part of the night crew). There I learned of the revolutionary way that Voulkos, Soldner, and numerous other clay luminaries had experimented with clay as an expressive art form rather than as a continuation of American functional pottery traditions. The spirits of Voulkos and Soldner and their colleagues were still hovering there, and Frimkess made ceramic history from Greece to China to America come alive.

I had always been interested in the sculptural nature of traditional African and early Jomon Japanese art, as well as with Wendell Castle's wooden sculptural furniture. I also loved the concept of creating multipurpose sculptural objects and had embarked on a series of wine decanters camouflaged as sculpture as the focus of my master's thesis

project. Lee Nordness visited Otis and chose one for the historic "Objects USA" show, but the box, larger than me, was lost in transit to the New York gallery.

Meanwhile, one of my mentors, Herman "Kofi" Bailey, a childhood friend of the family, had just returned from Ghana. He and several other African American artists and writers had gone to West Africa to live and work at the invitation of Kwame Nkrumah, who was leading Ghana toward independence. Kofi was the key to my deepening interest in West African art, culture and philosophy. His stories about Africa and her people, his discussions with W.E.B. and Shirley DuBois, and his love for the art, music, and expectations of an independent Ghana led me to travel to Ghana, Togo, and Dahomey (Benin) in 1975 with the African American Institute and Howard University. I returned transformed by my experiences from Cape Coast to Ganvie Village in Dahomey. I felt that I belonged to an extended family of African American artists who had been making their pilgrimage to the Motherland to see it first hand and not over the TV tubes.

The convergence of West African mythology, ritual and spiritual usage of clay, wood, metal, and fiber arts, and the sheer energy permeating life and art during those historic times of the civil rights movement in the United States and Pan-African liberation events caused my art to change. The Chinese-influenced stoneware and West Coast clay experiments were supplanted by an exploration of the aesthetic and ritual context which informs West African, Southwest Native American, and Japanese ritual tea ceremony raku ware. These cultures shared a commonality in involving their art in the quest for enlightenment in life. They also shared in creating a distinctive beauty in lustrous surfaces, and they emphasized the interaction between the medium and the maker as process rather than as production. Further, the individual ego of the artist was not as important as the expression of traditional cultural values through the works. This provided a bridge for me to express the essence of American life and culture from the perspective of my experience.

Over the years, my style has revolved around three general concepts/themes: A. Figurative and narrative sculptural vessels created as an homage to "Sepia Sisters" as carriers of cultural values, women's issues, and ndu (life force); B. Symbolic lidded containers and other forms with sculptural elements, called "Spirit Vessels," meant to contain remembrances of loved ones, mentors and spiritadding persona; and C. Raku wall sculptures with painted, glazed and stained face masks, inset in plate-like enclosures which connect to African (and Japanese) masking traditions. They symbolize multiple stories – the histories of the Middle Passage, biblical stories of pain and transformation, and are also records of family, friends, and mentors. They are also universal and operate as "Power Objects," created to give energy, strength, faith, and to provide a point of contemplation for healing purposes.

I stay in the field, working against the odds and using very simple means and processes in my work while simultaneously teaching beginning students, mostly non-art majors, at Florida A & M University in Tallahassee, simply because clay is my teacher and I learn more about it by sharing my knowledge with students. Through the transformative properties of clay, I am learning about the secret laws of life. I do not see myself as a master of the material but as a partner with it. I simply love it.

I have several friends who are potters, and we sometimes work together, sharing raku firing and life, as I did with my clay-partner for twenty-six years, but we don't dwell on technical or aesthetic matters, as we are each finding our own way with the clay. I suppose, however, my work is linked to other post-modern artists who are utilizing commonalities among various cultures to create a contemporary art which operates independently of the mainstream New York/Los Angeles museum and gallery world. I consider myself to be a Southern artist even though I was raised in Chicago and lived out West, so my work is linked to southern and diasporan traditions. It is linked to the international movement of artists of African descent who are redefining their art to meet the needs of spiritual survival and transformation in an industrial, commodity-driven world. It is an art generated from the inside out. Simultaneously, people and potters from all ethnic backgrounds have responded strongly and favorably to my work, as it bridges ceramics, sculpture, and painting and speaks both to the past and to the future.

In spite of my showing in many galleries and museums across the country since 1968, I feel I have one foot in and one foot out of the field. I am known nationally within the sphere of African American art, and in the Southeastern regions primarily as a clay artist. When my husband and I came to Florida in 1968, we were immediately recognized in Miami and throughout Florida. For a while, I was active in Florida Craftsmen and became a regional director after we moved to Tallahassee in 1973. By 1975 we were transforming raku to our African American experiences and called our work "Afro-Raku." I believe that Curtis and I African Americanized raku by transforming it to represent a particular African-based aesthetic. Others may have also been creating an African-styled raku at the time, but we had stopped reading magazines by the late 1970s, and we didn't run into other artists doing this until the 1980s.

I needed to drop the influence of what others were doing in order to make room for introspection. I needed to know clay from the inside out and to allow it to speak through my work as a conduit for its own life-force like the "silent thunder" of peasant Japanese clay works and the "Big Eye" effects of forceful folk art in the Ghana of my fondest recollections.

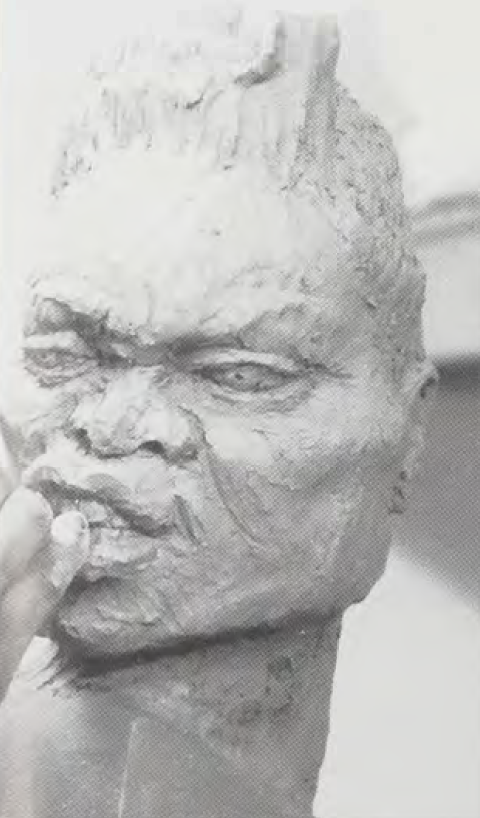

Janathel Shaw

Much of my work gives you a slice of my personality. I'm a direct individual. I explore provocative issues through my art that I feel need addressing on a broader scale. I wouldn't say I'm an activist, but I take special interest in events that affect me as an African American, a parent, and a woman. I often find that people don't know what to make of me based on the social/political context of my work. They think I'm an angry black female. Well, issues such as racism or sexism make me angry. My stance, however, is not always confrontational. Nurturing, compassion, joy, empowerment, and sorrow also describe my work. If I had to describe my directive, it would be that of social commentator.

Much of my work gives you a slice of my personality. I'm a direct individual. I explore provocative issues through my art that I feel need addressing on a broader scale. I wouldn't say I'm an activist, but I take special interest in events that affect me as an African American, a parent, and a woman. I often find that people don't know what to make of me based on the social/political context of my work. They think I'm an angry black female. Well, issues such as racism or sexism make me angry. My stance, however, is not always confrontational. Nurturing, compassion, joy, empowerment, and sorrow also describe my work. If I had to describe my directive, it would be that of social commentator.

My earlier forms were based on vessels, womb-like structures. I'd studied traditional African pottery and the earlier work of artists such as Martha Jackson-Jarvis for inspiration. I enjoyed the pregnant quality of the forms and the allusion to spiritual dwellings. Over time, my sculptures have evolved from organic shapes to torsos and strongly delineated forms. If you were to ask me what my style is, I'd describe it as symbolic, highly textured, bold in contrasts and color, socially oriented, emotive, and, hopefully, thought-provoking.

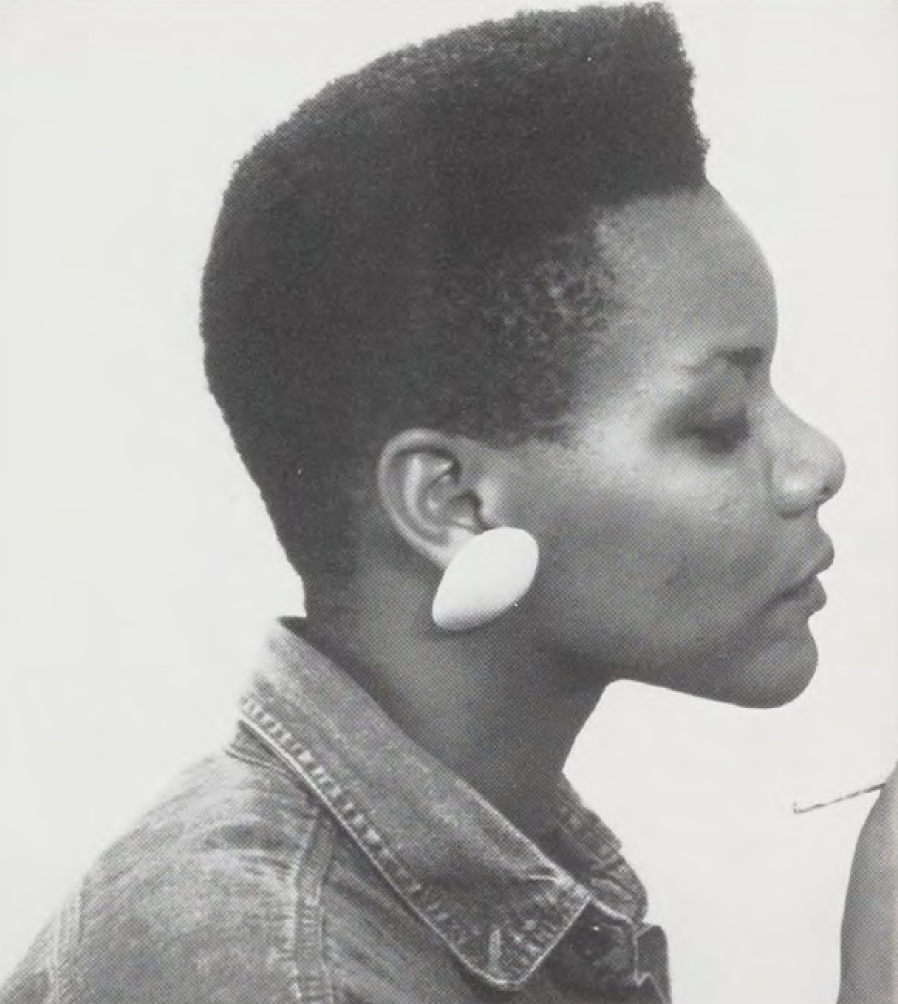

My introduction to the medium was through Martha Jackson-Jarvis, my instructor at Duke Ellington School of the Arts. Later, I became acquainted with the work of Winnie Owens-Hart, Elizabeth Catlett, and Camille Billops. This led me to search for other African American sculptors and ceramists who explored the human condition. Another notable figure was Robert Arneson. His irreverent, satiric, and exaggerated forms were a real draw. Catlett and Arneson took texture to new heights, explored pivotal issues, and pushed the medium in ways they basically felt it should go. The other lure was the clay itself. I found the malleable medium appealing and challenging.

When I construct my forms, my primary focus is on evoking a mood, and eliciting a message. My aim is to definitely incorporate my cultural heritage into my work.

Creating art is a demanding vocation. It doesn't come with a guaranteed salary, so the main motivation is the art itself. It is a struggle having to work full-time, create work, manage a family and pay for studio space and supplies. What keeps me going is that I'm determined to make my mark. I'd like a young student to be inspired by my work as I've admired others who set strong examples in subject and aesthetics.

As artists, we validate history, whether our art is social, political, architectural, or just interpretive of beauty. And it's essential that we be supported.

Syd Carpenter

Each new object is in response to its predecessors and comes out of a necessity to broaden or re-examine an idea. The way my sculptures look is less a reflection of style than the need to find shapes, surfaces, and methods of building that communicate what the idea looks like. I am aware that process affects the look of an object and how it is perceived. I am also aware that good ideas can be burdened by inappropriate processes, so I am always willing to change the way I work. Of this, I am neither afraid nor suspicious. Solutions are fluid, with the "escape hatch" open at all times. There are recurrent themes in my work that are given new form with each reconsideration. I make new things in new ways to keep the conversation alive for myself while revisiting themes of self-portrait, family, and the passage of time.

style="width: 200px; height: 341px; margin: 10px; float: right;" />It was the atmosphere within the greenhouse potting shed at Tyler School of Art that drew me to clay. Rudolph Staffel was my instructor. He was less of a teacher than a facilitator. There was something wonderfully subversive about his ability to keep students questioning the possibilities. His stance was ideal for young artists/potters resistant to authority but still needing direction. The excitement of the clay process overwhelmed questions about content or form. I thought only of making glazes and learning new techniques while roughing it through long and exhausting firings. I gradually moved through the initial attractions toward appreciating clay as the most appropriate medium for my expressive purpose.

style="width: 200px; height: 341px; margin: 10px; float: right;" />It was the atmosphere within the greenhouse potting shed at Tyler School of Art that drew me to clay. Rudolph Staffel was my instructor. He was less of a teacher than a facilitator. There was something wonderfully subversive about his ability to keep students questioning the possibilities. His stance was ideal for young artists/potters resistant to authority but still needing direction. The excitement of the clay process overwhelmed questions about content or form. I thought only of making glazes and learning new techniques while roughing it through long and exhausting firings. I gradually moved through the initial attractions toward appreciating clay as the most appropriate medium for my expressive purpose.

Why does any artist persist in making art? Ideas multiply. If I want to see them realized, I have to walk into the studio and struggle through the process of making the object appear. I keep making them because I want to see what they'll look like. When the ideas stop coming for clay, I'll make them in another material. If statistics, politics, or the odds against maintaining myself in this endeavor were deciding factors, I would have chosen another path.

The use of organic forms combined with industrial shapes, interspersed with the human figure, is not exclusive to my work. The sculpture is informed by its contemporaries and what has come before; however, it is not dependent upon either. The territory mined by my work will intersect with the same territory being looked at by other artists. The idea of shared aesthetic threads among clay artists reminds me that I wish there was less of a need for writing by clay artists by and about ourselves and more examination of the work by those trained in art and craft criticism and history.

I bring to this "conversation" some issues that talk about what I know and respond to. There was a time for me when the universal appeal of an object was a marker of its significance. An object required universality to be taken seriously. Now I am looking for the small stories, the idiosyncratic details that position it in time and place. I hope my objects survive as evidence of my thoughts and experience and, most importantly, as a reference for the young ones who are to come.

As to whether or not my work is "in the field" ... My cynical side would translate that to mean, "Have I been accepted by the majority as a real artist making work, to the majority standard, based on majority criteria?" It would be counterproductive to expend concern over where I fit in. I'll leave that answer to someone who has a stake in the answer. I make the strongest visual response available in my capacity as an artist. An investment of thought, process, and compelling sculptural presence is rewarded by response and connection.

I have been very fortunate to have received an abundance of positive and supportive reaction to my work from many directions. Being in the field is important insofar as the greatest affirmation of my work has come from within the clay community. Additionally, I seek interaction with artists working in different media and aesthetic perspectives. These encounters offer an infusion of objective insight and challenge.

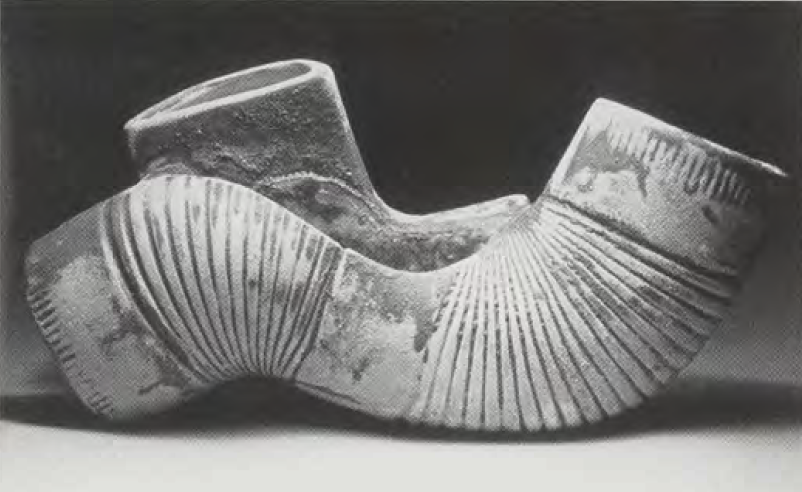

Teresa A. Williams

“Pottery provides all the ways in which a person may express himself. Here you have form, design, color, balance, rhythm, harmony, all in one.”– Earl J. Hooks[1]

I moved to Los Angeles from Cleveland, Ohio in 1959. During my teenage years in Cleveland, I was introduced to the arts at the Karamu House, a well-known local community art center. There I learned and practiced modern dance and ceramics.

I graduated from California State University at Los Angeles in 1974 with a BA degree in art. After graduation, I began working as an Adult Education teacher, raised a family, set up a home-based ceramics studio, and became more involved with clay. I continued to study ceramics at various summer ceramics institutions: Logan State University in Utah, Otis Parsons in West Africa, and Otis Parsons in Los Angeles. I read, and I attended ceramics workshops to supplement and expand my art education and technique.

Because I am a teacher, I cannot devote all my time to making pots. Studio time is limited, and I have to simplify my routine to achieve continuity and establish a sense of rhythm when I work. In order to accomplish this, I've limited the scope of my work primarily to making flower arrangement pots. I've also narrowed my choices of glazes, and I use only white stoneware, and high-fire clay. The current direction of my work is influenced by my experience as a flower arranging student. For the past fifteen years, I've been creating flower arrangement pots, which I find to be an endless challenge.

When I go out to work in my studio, I realize it's my special space where I can take risks and be spontaneous. I use slabs and coils to form my pots. The pots are assembled from previously cut and constructed forms at the leatherhard stage. The act of putting the pieces together is a kind of meditation for me. It's a process that remains alive and vital because of the problems each pot presents and the resolve I feel when each piece is complete. Solving the construction problems that arise lets me draw on the skills I've acquired in all these years of hand-building.

So far, my work has reached a limited group of people – you might say a specialized group who are mainly interested in flower arranging. With such a limited audience, why do I continue to make pots? It's simply a personal need I have. That need is further satisfied when other people buy and use my pots to satisfy a personal need they have.

As a studio potter engaged in actively producing work in the spirit of the pottery tradition, my goal is to continue striving to make a creative contribution to the field, despite not being in the mainstream of critical recognition. This is my motivation and my challenge.

As a studio potter engaged in actively producing work in the spirit of the pottery tradition, my goal is to continue striving to make a creative contribution to the field, despite not being in the mainstream of critical recognition. This is my motivation and my challenge.

[1]Elton C. Fax, Seventeen Black Artists (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1971) p. 218.

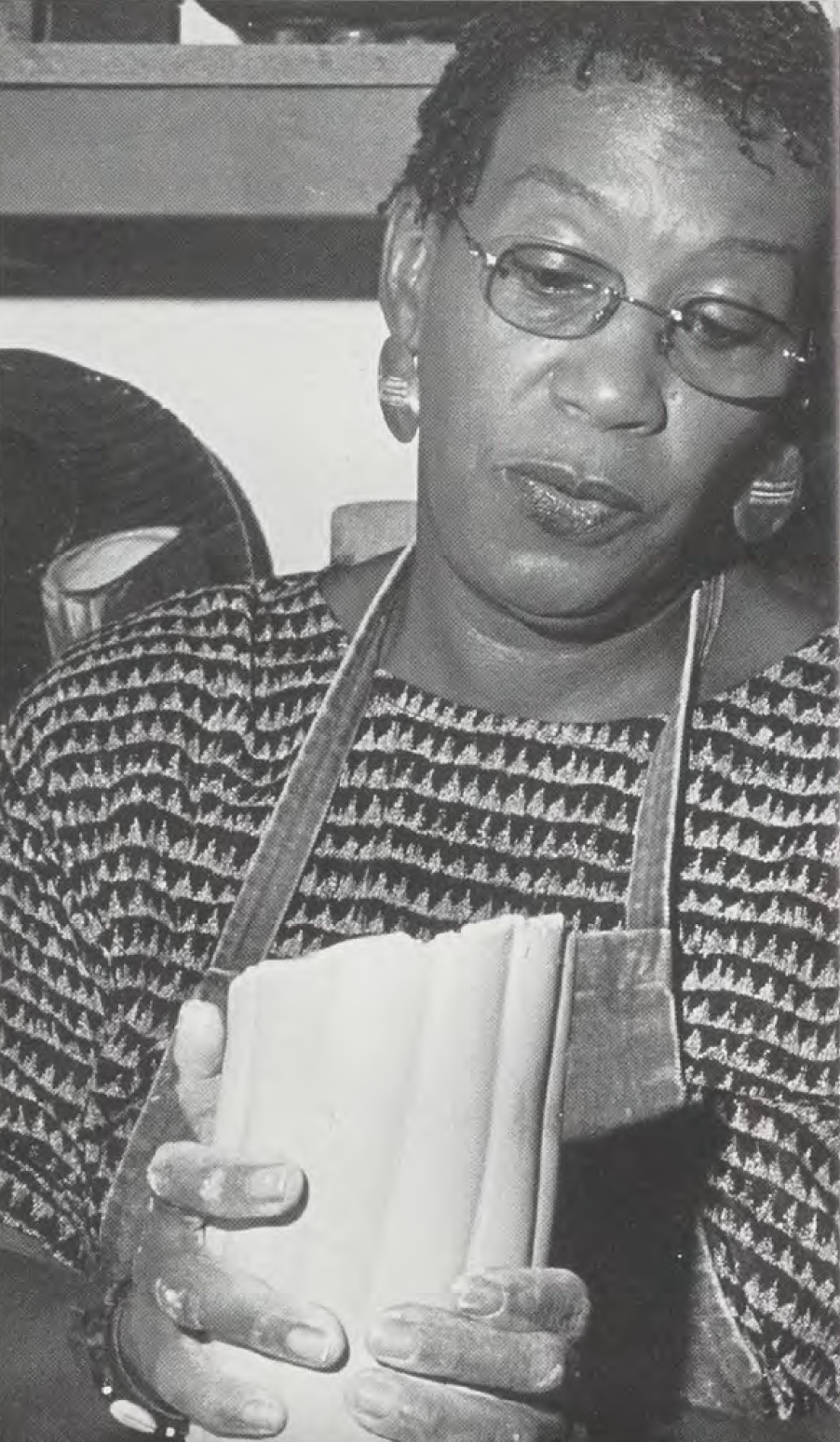

Barbara Madden-Swain

As a clay worker, I like to think that my primary focus is on producing individual ceramic pieces in stoneware, porcelain, and raku clay through a combination of hand-building and wheel-thrown techniques. There are times when I experiment by combining clay with other materials such as stained glass, photographic image transfer, copper wire, and reed to bring about or create new and exciting forms. Each and every one of these creative

"explorations" provides me with new opportunities necessary for continuing my work at different levels, resulting in unique individual pieces.

Winnie Owens-Hart, a Howard University professor, has had a major influence on me and my work. She not only taught me but served as my advisor as well. She was great, for she allowed me to be independent and yet grow at the same time. The African influences evident in my "Serengeti" series – the water drums, spirited animal forms, and the earth-tone glazes – I learned from Professor Hart, who had spent several years studying with Nigerian village women. She also taught me the handmolding technique which I use.

John Glick of the Cranbrook Institute was a major influence on my selection of ceramics as my medium. While searching for an undergraduate program, I attended a Glick workshop; it was my first potting workshop experience. I was so impressed by John Glick and his work as a potter, as well as his philosophy on potting, that I signed up for Ceramics I and II. At this time in my life (my children were grown), I had no idea that I had this interest and that my romance with clay was about to begin.

In 1986 I attended the Haystack Mountain School for three weeks. There in Maine, I was able to live, eat and breathe clay. I was now really hooked on potting – I was to be a potter!

In 1986 I attended the Haystack Mountain School for three weeks. There in Maine, I was able to live, eat and breathe clay. I was now really hooked on potting – I was to be a potter!

With the support of my family, my personal philosophy about clay and potting began to develop. I am very much aware of the fact that the basic working clays are the same all over the world, but I have a deep love for clay, form, and texture. I know also that clay forms can reflect the thoughts and movements of its creators. For me, research plays an enormous role in the creative process; it must be done, and as a potter/clay worker, I know that attention must be focused on the detail, for the detail enhances the uniqueness of any given piece. Therefore, research must be done. My artworks are not just exercises or accidental happenings; my work evolves from extensive research and a lot of love for the medium.

Of course, I love the challenge of making something from a nondescript lump of clay. The self-gratification is a huge plus factor, but it is

definitely gratifying when the public loves your work and buys it; it is even more gratifying when the public respects your work and asks for it. I also enjoy the challenges and opportunities of sharing at a potters' gathering and group firings. Being able to share with others adds a different dimension and depth to the clay working experience. I hope that the sharing of my experiments will challenge others to move forward.

Although statistics, climate, and tide flow indicate the market for ceramic art is perhaps disappearing, I feel that I am fortunate that I've retired and can devote my time and energy to chasing my dreams. My home and studio are at the end of a road in a picturesque, natural setting and various wildlife often stop by to see what I'm doing. Who could ask for more? As it is, I detest driving, and I do love home; therefore I have the best of two worlds. Had my art form developed earlier, I probably would have been an art teacher. I enjoy my late-night researching forays, however, and my early-morning creative moments. Most of all, I do enjoy being able to donate my work to be used by various special causes, whether a YMCA fundraiser or a symphony orchestra auction.

I love clay; I love being a potter!