Whatever We Touch is Touching Us: Craft Art and a Deeper Sense of Ecology

For M.C. Richards, Fran Merritt, and Bill Brown

A few years ago I participated in a council of elders at an Omega Institute conference on aging led by Ram Dass.

About 50 of us over the age of 60 sat in a circle surrounded by larger circles of younger people. Ram Dass explained how those of us in the inner circle could begin to center our energies and draw our powers together by telling our stories. He pointed to a large cushion in the center of our circle. There was a long, white Native American pipe resting on it. "When you are ready' he said, "when it is your turn, stand up, go pick up the pipe and return to where you are sitting in this circle. Breathe some. When you feel the energy in your voice rising, say: 'And'...then tell us your stories. When you have said what you have to say, say: 'SO BE IT' and return the pipe to the cushion for the next AND."

I love this AND. That we and us, our stories, are AND and AND's stories. Stuart Kestenbaum tells me it is my turn with the pipe. And...

The Black Jacket

Some years ago I lived for several months in Washington state, sharing life and a house with two of my fairy-godsons. Johan, then 14, had come with me from North Carolina to begin high school in Olympia. Michel was in his senior year there at Evergreen State College. The house we rented was unfurnished and, except for a few things we had brought with us, everything we needed we either made, found or purchased at flea markets or second-hand stores.

One Sunday morning Michel proposed a trip to a small town he knew of halfway out on the Olympic Peninsula, where, he said, there was a whole street of second-hand stores. After a long and eventful drive, we eventually found the town.

In the first store we entered there was this jacket: black, simple, almost formal. The price tag said $4. I tried it on and it fit perfectly. But I don't often wear jackets and I didn't expect I would have occasion to wear quite so refined a jacket. So I hung it back up on the rack.

We went from store to store finding a few of the pots and pans we needed. When we had had enough of looking through bins and racks and going from shop to shop, we made our way back to the car. It was parked in front of the first store we had entered, the store in which I tried on the black jacket. When we reached the car, I excused myself and went back into the store and tried on the jacket again. I looked at it in a mirror and took it off and put it on again. I both wanted it and didn't think I needed it.

Finally, the woman who ran the shop, seeing my indecision, said, "Mister, you look so good in that jacket I'll give it to you (pause) for $2." Well, I couldn't refuse the generosity of an offer like that, 50% off! So the decision was made for me. When we got home, I hung it in my closet thinking perhaps I could wear it for Halloween.

The next morning, I had two errands to run. First, to the lumberyard to buy 2 x 4s for a futon platform we planned to build. Then to the laundromat to do our week's wash.

I was already at the door when I remembered the black jacket and thought to go back in and put it on. So I spent the morning eyeing 2 x 4s and doing laundry wearing my new second-hand black jacket, and somehow it turned these chores into something else - something that felt special, memorable, conscious, like a ritual, or a moment of grace. I had been in that laundromat several times before, rushing, especially through the folding when the clothes were finally dry. This time, and I'm convinced because of the jacket, I took time with the folding, slowing down enough to enter it. I remember folding a sheet - stretching its whiteness out and then doubling it over my black chest doubling it again over my black arm where I sensed its weight, felt its warmth and caught its fresh odor.

The following day I made a trip into Seattle where I spent a few hours in the Seattle Arboretum, again wearing my new old jacket. I walked around, pausing in front of one tree and then another tree. The trees of the Pacific Northwest are huge and stately - awe-inspiring. There is so much cold rain in Seattle that many of the trees there have covered themselves with mosses and lichens and ferns, their trunks resembling dancers wearing knitted leg warmers. Each trunk its own shape, making its own gesture, in its own costume.

Standing among them, I sensed my own trunk. I could feel my roots moving into the earth from the soles of my feet, my spine's sure spiral towards the sun, my skin's slow dissolve. And in my treetops this gentle wind kept whispering, "Everything is art when you are dressed for it."

Everything, everything is art when you are dressed for it.

On the Day John Cage Died

On the day composer John Cage died in 1992, I was in East Dorset, Vermont. I woke early that morning, a little after four, staying in bed a while to read a back issue of the New York Times Book Review. A book that Carol Gaskin had written to tell me about and to recommend was reviewed in that issue: The Care of the Soul by Thomas Moore.

It was a favorable review with several quotes from the author. One short sentence struck me: "No moment is innocent." I wrote it down in my journal.

At noon, M. C. (Mary Caroline) Richards called from Pennsylvania. One of our friends had been hospitalized with cancer. We spoke about her and about Burt and Ragnar, both of whom had died suddenly of heart attacks in April. We talked for some time about illness and death, the loss of friends that we were of an age and in an age when there would be more of it in our lives and how we might prepare for it.

She called again, just a couple of hours later, to tell me that John Cage's secretary had just phoned her to say that John had died. He was making a glass of iced tea for Merce Cunningham when he suddenly collapsed, only weeks before his 80th birthday. John had been M.C.'s close friend for almost 50 years. Indirectly, he had been one of my teachers. I admired him and his "sunny disposition" enormously.

A few years ago, M. C. was interviewed on tape for a television documentary about John's life work. She said that he carried an energy that was larger than his person, "an angelic energy," is how she characterized it. He brought a new consciousness into our waking world.

At 5 p.m. I turned on National Public Radio to listen for a news report of his passing, but his death had come too late in the afternoon for an obituary to be prepared. "Fresh Air," an interview program that followed the news, however, re-broadcast a short excerpt from an interview with him made a year or so before.

There was his gentle, slow voice full of wonder, inquiry and vision. Several times during the few minutes he spoke he said, "Every act is virgin, everything is new." I felt as if he was talking directly to me - a farewell word.

Later I took a walk down the road I had walked every evening that week, repeating John's parting words as if they were a mantra: "Every act is virgin, everything is new." You are seeing that tree being a tree for the first time. Every sound and silence you hear is part of a continuous natural music composed in this moment. Every step I take on this road is occasion for a new freedom in my body.

I came back from my walk elated, full of delight. I opened my journal to add John Cage's words to it.

Writing directly after my morning entry, I added to Thomas Moore's, "No moment is innocent," John Cage's, "Every act is virgin."

No moment is innocent/every act is virgin - everything is new for a living reason.

Ecofeminism

One free evening, at Pendle Hill, last April, Elizabeth Watson gave a lecture in the meetinghouse on "Women in the Bible" which I attended. She spoke of seven women and then imaginatively revisioned the story of one of them, Zaporah.

As an aside, departing from her text, Elizabeth Watson reminded us that in the story of Genesis, it was Adam who named things: "You're giraffe, you're elephant, you're grass, you're woman.

Then she told us that Ursula LeGuin has written a short story in which she retells this tale. Its called, "The Naming," and in her telling of it, it is Eve, not Adam, who does the naming. "Oh. Yes, yes, you call yourself giraffe? You say elephant is your name? You're grass being grass? Yes, and my name is woman. I am woman!" Something like that, if I remember correctly. I wrote "Ursula LeGuin - The Naming - Eve" in my journal and then returned my attention to the continuing lecture.

Early the next morning, I attended a Quaker Silent Meeting in that same meeting room. I sat there in that honey-dense silence with my eyes closed, holding my stone, meditating, as I often do, on the fact that we are fundamentally water, muscled water. From Emile Conrad- Da'oud, I had learned that it is a misconception to think that we ever leave the amniotic fluid.

After about 20 minutes my eyes popped open involuntarily. There in the empty center of the meeting room sat Eve as if painted by Botticelli. Her legs were spread wide. She was leaning to her right, cupping her right ear in which there was a large trumpet-shaped blossom about 14 inches long. I recognized it as a flower of the "Bella donna" angel trumpet trees I had seen a year earlier in Hawaii. Its Latin name is Datura. In the musical native Hawaiian language it is called "Nana Honua" which is translated as "gazing earthward."

There sat Eve, gazing earthward, listening with her ear trumpet. Oh, how she was listening. Boy, oh boy, how

she was listening.

Rudolph Steiner told us that our ears are the threshold, doorways to worlds of spirit and depth - that imagination, inspiration and intuition are arts of the ear - seeing, breathing and knowing through our ears. They breathe into us 66 before they can be exhaled out of us.

Fear and Love

Thirty years ago, in the middle of a busy and ambitious period in my life, I was suddenly struck by a serious illness. The prognosis, which eventually proved to be mistaken, was terminal. But I didn't know that then. I thought I was dying, and in those days I feared death.

I sold or gave away everything that would not fit on the back seat of my automobile, and drove to Southern California, then the center of experimental, alternative healing in this country, where I tried everything. One of the things I was told by several of the healers I visited was that fear was at the source of my illness and that to restore my health the only thing I need do was to let go of my fear, "cut it out," and substitute it with love. I didn't know how to do that. Are fear and love adversarial opposites? Why did I have this small and stubborn intuition that there was something of value in fear, something to embrace?

My inclination, my only choice, was to take on my fear. It was all I felt I had. I wanted to know it. But no one could tell me how to do this, especially how to begin at a beginning with it. Nobody, it turned out, could heal me. Healing isn't done to you or even by you. You receive healing. I would have to find my own way of opening myself to it.

Eventually, after several failed attempts in which I tried too hard and was too psychological, I remembered a lecture I had attended given by Moshe Feldenkrais, an Israeli somatic healer and learning theorist, who recommended pleasure as the most powerful way to self-healing and true, that is, embodied, learning. He was very serious about pleasure. Is pleasure indulgent? Could I give myself permission to pleasure?

One of my pleasures is doodling. I've done it all my life. I find it fun. It helps me through difficult times and boring meetings by focusing my attention. It's become a way I meditate and it's always full of surprises: images that I do not make but that appear.

So I took the word fear into my journal and doodled it. I wrote it over and over again. I drew it by echoing the lines of my own handwriting writing it. I wove its letter forms in and out of each other. After a long time, more than a year, I finally saw what was then obvious, that every time I drew the word fear, three-quarters of that time I was drawing the word ear: f.EAR. There is an ear in your fear, Paulus. Open it, listen. But how?

Almost immediately, I saw that "EAR" was also right in the center of the word heart: hEARt. Was ear a bridge between fear and love. Drawing heart now, I discovered the word art in heart and was profoundly encouraged, heartened, to see that in heart, ear and art overlapped, becoming one. I had previously associated art with the mouth, with self-expression. Now I was discovering art's connection to ear, as a way of listening and receiving and taking in instead of always giving out; not making image, but receiving image, being gifted by image. I can't tell you how helpful that discovery was for the full recovery from my illness.

A few years later I spent six months in Tasmania, Australia, the home of the first green political party, studying "Deep Ecology." While "downunder," where everything is said to rotate in the opposite direction, I noticed that my doodling of heart had rotated as well. The "h" that begins heart in the western hemisphere of my brain had made a dyslexic shift in the southern hemisphere. I saw HEART now as EARTH. From heart to earth - of course, Why hadn't I seen that before? Why was I seeing it just in time?

Later, after my return to the United States, I saw more when the words heart and earth veiled in a chiasmus across each other to become HeartH, just when I was introducing altar-making and ritual to my clay work and workshops.

A movement of imagination from FEAR to EAR to HEART to EARTH to HEARTH to ALTAR - to thanking and praising and gratitude doodling into the tissue of my subtle body.

One of the things I've come to know in my life is that ideas do not belong to people - my idea, your idea. I've come to know that we are all antennas, continuously receiving an intelligence larger than what we think of as our own. We are innately capable of receiving the gold the golden rod is giving away. We don't need computers as access to an age of information. We need an ear for the ecological unconsciousness of the cosmos in this age of consciousness, of knowing whom we are related to, interwoven with, part of.

In the thirty years since I thought I discovered the EAR in FEAR, the intimacy of HEART and EARTH, I've come across several people who have discovered the very same thing. None of us makes claim of originality. Some of us call it synchronicity or morphic resonance. I like to think of it as a call from the earth itself. She's calling, inviting me, us, to hear her in my, our hearts. I may sound simpleminded. It is simple-minded. Unless I take her call to heart and make love with her, I won't survive as a species. I mean this seriously. Water is not an 'endangered resource.' It's the fluidity of life. We live on a daily income of sun.

Awakening, I finally see that it is no accident that the word we use to name our mother, EARTH, and the word we have chosen to name our innermost core, HEART, the place where we actually experience compassion and communion, are the same word, made of the same ingredients. I pause at the hearth. Give thanks and say, H.EAR/HERE!

In Taoism and the practice of Qigong, fear has an organ, the kidneys: an element, water; an associated animal, the bear; a color, midnight blue; a season, winter; and a direction, North. Love, on the other hand, is associated with the heart, with fire, the crane, the color red, summer, and the South. When fire and water, when fear and love are brought together through intent, a healing mist is born that tempers love and transforms fear into wisdom. Experienced in this way, love is not a matter of getting rid of our fear, but of making love with our fear, taking it on. Love needs fear in order to know itself. Fear needs love to alchemize it into wisdom, heart loving kidneys, the mix of fire and water, red mixing with blue, the dynamic cycling of North and South, winter and summer, the interplay of Yin and Yang, inhale and exhale; the healing life force in thin air.

Serving the Soup

In the Spring of 1987, I received an invitation to be an artist-in-residence for the summer at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. I declined, but asked if there might be a position available in the school's kitchen. I thought that I would be more comfortable, perhaps make a more easeful relationship with the students, faculty and staff, if I came in through the back door, so to speak, rather than to carry the title 'artist-in-residence.' So I worked in the kitchen.

The food prepared in this kitchen was excellent, fresh, tasty and inventive. The head cook, Rosemary Foreman, was a cheerful young woman who was an especially inspired soup-maker. It was the first thing she attended to when she arrived at 9 a.m. after all signs of breakfast had been cleared away. Some days she made two soups. Just what soup she made was a dialogue between her musings on her long drives to work and what fresh, locally-grown materials were available that morning in the walk-in refrigerator. My job was to clean and slice the carrots, dice the potatoes and prepare the parsnips.

The kitchen was busy and Rosemary was a little behind time one day early in the summer. It was her custom to fill a dozen or so bowls of soup, leaving them on the counter of the open pass-way between the kitchen and the dining room for the students to pick up while she went about her task. She would keep her eye on the supply of soup bowls and when there was only one bowl left she would fill a dozen more, and so on. But she had no time for that on this particular day and asked if I would take over. From that moment on, it became one of my daily tasks, the one I most looked forward to and most

At first, I did as Rosemary had done, filling a group of bowls, waiting until almost all had been collected before filling some more bowls1. But soon I began filling bowls one at a time; when it was taken, I'd fill another. Then I began to wait until someone came up to the pass-through before I filled the bowl. Eventually it slowed down even more. I would lift a bowl with one hand, ladle the soup with the other, put down the ladle and offer the bowl with both hands to whomever was there waiting for soup. I would look into their faces, their eyes, say their name if I knew it or ask. Occasionally, a few words were exchanged, or a greeting. There was a lot

of smiling, but mostly what passed between us as I served the soup was said in silence. Lines began to form, but no one complained about the wait. Rosemary was delighted as more people than ever were eating her soups and the space between the kitchen and the dining room felt as if it had become smaller, more intimate. I especially enjoyed those occasions when a potter would bring a bowl he or she had made for me to fill.

It was a new experience for me, this serving of the soup. At first, I was just doing something and then suddenly I was serving, standing there ladling, offering, making contact. Simply serving soup, "little dance, a little communion. This bowl is for you, and this one? It's for you."

One journal entry for that time reads, "It looks like I am an artist-in-residence here this summer, after all. My art? Serving soup!"

Anneal's Ashes

There was a year when M. C. was teaching in England and I was living at our farm and studio in northeast Pennsylvania. We wrote each other frequent letters. In one, M. C. spoke of changes she felt internally and asked if I would help to find a new name for this new person she felt herself becoming. I wrote back immediately offering the name, 'Anneal,' for her consideration. She liked it and for the remaining 31 years of our friendship, that was my intimate name for her: "Anneal, my soul's main mate." I don't remember choosing that name, thinking it up. It simply came.

Later I looked it up in a dictionary and discovered that it wasn't a noun, a name, but a verb, an activity: a process of heating and slow-cooling in order to strengthen and reduce brittleness; to temper, from the Old English, "to kindle the fire, to ignite the heart." M. C. was her noun. "Anneal" was my playmate's verb, how we lived in the world together.

At the end of her life, I made several trips to see her at Camphill Village in Kimberton, Pennsylvania. She was frail, using a wheel chair, nevertheless preparing herself. Looking forward. In one of her last poems, she writes herself into fuller world where she will have no biography, where she hoped to 'backpack in the hereafter.' She lived life as the big art to the last. The morning of our final day together, just days before she died, I woke with an image that came with me from sleep. In it, I was wedging her ashes into clay.

In hindsight, our conversation that last morning, an early, balmy September morning, was one of our truest - a completion, a farewell, a forgiveness, and a thank you. We sat at the edge of an apple orchard bowing to each other.

Before I returned her to her room so that she could rest, I told her about my dream and asked her how she would feel if I were to wedge some of her ashes in clay and then pinch a pot or several pots, offering bowls in which I could return her mineral body to the earth's mineral body. She laughed and smiled broadly and said, "Yes, Paulus, you do that."

Later that day, she spoke of it again. "There are all these stories," she said, "about potter's ashes becoming glazes and of other potters making urns for storing their own and each other's ashes, but this suits me: "clay from the loam of earth given to my hand handing it to you, your handling my debt, my death, returning me to clay; from dust to dust."

In the days before she died she made arrangements, and during one of my return visits to Camphill Village after her death, to help organize and distribute her belongings, I was given some of her ashes. I took them with me to Haystack Mountain School of Crafts that summer. M. C. had loved Haystack and contributed so much to its innovative spirit in its early years. Every fall when she would attend board meetings there, she would stay an extra day or so to lie on the sun-roasting, stone boulders and listen to the voice of the sea.

My thought was to pinch a bowl, fill it with some flowers, some strawberries and two or three of her poems, place the bowl among the rocks, light some incense and let the rising tide take her. But as it was, I could not get myself to pinch the clay with ashes into a bowl. I wedged and re-wedged the clay and ashes daily - waiting. Something else, something simpler, more the way imagination flowed into her than into me, was uttering very softly in my ear.

Finally, it was my hand that did it, that reached for a bit of clay and formed it in my palm into a single, small stone that I placed on the wooden table before me, where light illuminated it and cast a shadow. A single stone and its shadow; it appeared monumental and musical. For the next few days I just looked at it and listened.

The day before I was to leave Haystack, I made a handful of stones, put them on a moss bed with some flowers in a bowl and carried them down to the rocks at low tide.

Home now, I've made hundreds of stones and placed them in lines like sentences on the gleaming wood of my dining room table. My plan is to take some of them to the farm next week when I drive north with Suzi Gablick and we stop to spend the night with Laurie Graham and Larry Wilson, who lived there with us all those years. My intent is to drop or to plant individual stones about the property. Burt's ashes are there and Raja, a dog M. C. loved and cared for, is buried near the barn. When I return home my plan is to send a few of the stones to her friends at Camphill Village and to Julie for her M. C. memorial garden in Sacramento and to Deborah in Boulder, to Donna in New Mexico, Andrew in West Australia and several other of her close friends.

This is what I have been imagining these last few days: that each of the clay and ash stones is a word and that each word is a seed that I can plant. "All forms are language," she often reminded us. Which reminds me of a book she admired and read more than once. In it, Abram asks what it was that caused us to lose our imaginations for the more than human world, or 'Natura' as M. C. like to call her. Abram makes the case that it was the development of vowels in the alphabet that initiated our estrangement and ends his book with a rapturous coda in which he says that it is words that can now bridge the gap, heal the distance. "Plant words," he says, "like seeds under every stone and in the roots of every tree," or something hopeful like that.

So here, her final poem, a few seeds planted in or placed on the body of the earth in Pennsylvania, California, Maine, Colorado, North Carolina, New Mexico, on Tasmania and in Denmark. Where the ocean, rain and ground water will weather the words and return them to the geological system for which she had such enthusiastic imagination: fully, finally, 'Annealed.'

Always We Are Eating and Drinking Earth's Body, Making Her Dishes

Enchantment is nothing more than the recognition of the world's spirituality and the exposure to its influence. An influence is primarily an 'in flow' and to be enchanted you have to allow the spirit of the world to flow into you. -----Thomas Moore, from "The Re-enchantment of Everyday Life."

Inspired by a comment overheard when I was four years old, "to dance is to spring from the hand of God," I backed into adult life attempting to become a 'trained' dancer. One night, during a pause in a performance of an especially vigorous dance, a voice inside a field of light on the opposite side of the stage, echoing through the muted musical score, asked, "If this is dancing on a stage, how will you dance in life?"

Soon after, and seemingly by chance, I found myself watching the highly regarded potter, Karen Karnes, working with clay on a large wooden potter's wheel. She sat there as if on a throne. Her movements were assured, flowing and calm. Working slowly, she appeared to grow in stature with each pull-up of the walls of the cylinder she was throwing. Without taking her eyes off the clay, one of her hands reached for a sponge in a water bucket to the side of her, her fingers finding and lifting it in a gesture of such knowing and natural grace, that I was suddenly overwhelmed with a longing to learn that dance. The bridge for me at first wasn't so much the clay itself and what one made of it, or so I thought, but the dance one dances with it. When I told two of my friends that I wanted to learn to throw, both suggested that I attend a summer session at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts; that M.C. Richards, then Karen Karnes' studio mate, taught there often, and that she was a poet and a philosopher as well as a unique clay artist. So I decided to take a three-week sabbatical from my life as a performing artist, to move from stage to studio.

Haystack was a revelation: altar-like; perched on a Maine coastal hillside; rhythmically, step-by-step, descend ing through pointed firs to the 'serious sea.' M. C. turned out to be just the kind of teacher I had long hoped to find. We became instant friends, soul mates. At one point during the first morning of our workshop, she turned toward me and said, "It's not a matter of having taste, but of having the capacity to taste what is present, to behold." I've been thinking about that, working to embody attentive presence, ever since. It initiated a conversation that continued, in mutual support, for 40 years. By the end of those first three weeks at Haystack, I was in love with clay, with M.C., with the human and more-than-human community of this small outpost of a school and the then re-emerging world of the handcraft arts it introduced me to.

So I

became a potter and, almost immediately, a teacher; first at Pendle Hill, a Quaker retreat center, and then at Swarthmore College where we built a two-way wheel so that I could join hands with the students and introduce them to the dance of throwing-together.

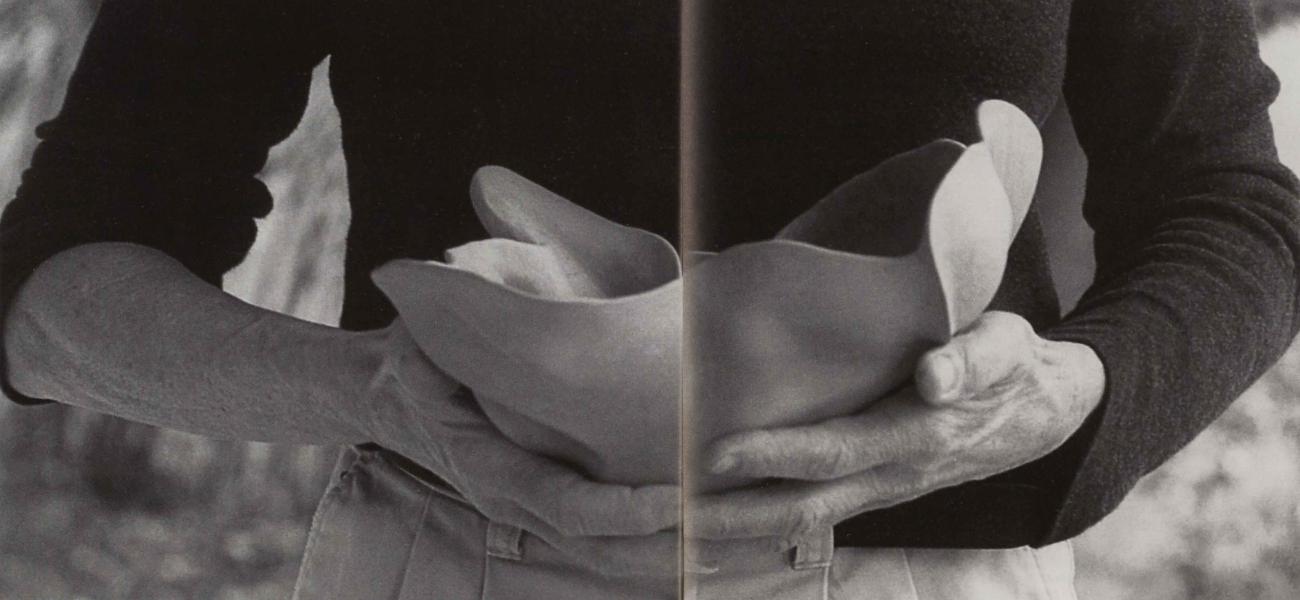

M.C. and I moved with friends to a farm in northeast Pennsylvania where I worked as a production potter for some years. One morning, frustrated by the interference of thought while attempting to meditate, I got up and went to the studio where I prepared a ball of clay, thinking to climb up on the wheel to start the day's work. Instead, I sat down again, melting, this time into a deep thoughtless state. A half-hour later, when I opened my eyes, there, in both my hands, a small pinched bowl, received as a gift. I've been pinching clay ever since, fascinated by its rhythmic slowness, its tactile sensuality, the intimacy of cellular connection, as if I were a partner in a classical 'pas de deux' or participant in a contact improvisation.

Soon after, I began receiving invitations to present workshops in slow pinching. One of the invitations came from the Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina, Haystack's southern sister. Its director, Bill Brown, had worked as assistant director under Fran Merritt at Haystack. Both men were visionaries who together had created a new model for non-academic, supportive and encouraging craft education. Bill and his wife, Jane Comfort Brown, welcomed warm-heartedly what I brought, and how I responded to Penland's program. They arranged for me to spend the following year there as an artist-in-residence. Bill gave me a studio and said, "Do whatever you want." During that year, a long letter I was writing to some former students at the Wallingford Potters' Guild in Pennsylvania about pinching became a book, Finding One's Way with Clay. It had the good fortune to be published at a moment of exponential growth in the craft-arts and has had a life of its own for 30 years, encouraging readers, encouraging me.

At first, all of the workshops I offered were about hand-building with clay. I tried to create an atmosphere in the studio that would be slow, quiet and focused. I was less interested in fostering expressive creativity directly than I was with offering an opportunity for receptivity and radical intimacy. Several questions, that did not require definitive answers, fueled the underlying inquiry of the workshops: What is clay? Why do we create? Why now, when the seductions and shadows of technology are overwhelming our resources? What is clay's function in the ecology of the earth? How to cultivate a craft of soul?

These questions, as real questions often do, enlarged the palette and introduced me to other primary materials and alternative choreographies of working with them. I began offering workshops in paper, weaving, poetry, doodling, needlework, altar-making, color, chance procedures, and, most fruitfully, for the past decade or so, a workshop I called, Soul in Slow Motion: The Making and Keeping of a Craft Artist's Journal. Something important and deep happens when we build the nest in which we birth our creative-evolutionary lives and carry our questions. I presented the journal, not as a documentary tool, but as a portable studio - as soul's kitchen.

During the decades that I gave these workshops, an inner picture of 'the life of clay' began to surface. The textbook that I had studied after my first session at Haystack had spoken of clay as an inert material and gave no sense of what the dynamic function of clay in the loam of earth might be. But since then, the work of Dr. Graham Cairn- Smith in Scotland, NASA's 'Life from Clay' theory, the Gaia hypothesis, systems theory, deep ecology, etc., have opened that picture and affirmed the intuition we have held all along: that clay has a life and an intelligence; that its origin is stardust; that the crystalline nature of clay is hospitable to enzymes and proteins raining down onto the body of the earth to form our original DNA. We are formed from clay - are souls in clay form. From stardust we come and to stardust we shall return. We know now, for certain, that we do not live in an inert universe. How to work with clay knowing this? How do we embody information so that a living material becomes a threshold for healing our deracination from our true, our wild natures? Over the years I've kept listening for clues to the secret lives of primary materials: the inner life of metals; of wood; the cosmic mesh of matter and energy in this weaving and woven, colloidally-fibrous universe.

Working with clay, listening for its meaning in life, and in my life, imagining it in the feedback of my journal practice, opened me to a deeper sense of ecology, to the web of life in this 'more than human world,' to lived epiphanies of mineral, plant and animal being. The magnetism cultivated by the constancy of question-asking began to attract clues. One such clue, powerful enough to change my life, was learning that there are 90,000 sense receptors per square inch of our fingertips! Picture that: 90,000 satellite dishes inhaling the being, the energetic pulse of the clay. 90,000 antennas exhaling our energies into clay. 90,000 rootlets broadcasting our sensitivities and our intent, grounding us in living intercourse with the loam of the earth.

Another spectacular clue came from a geologist at San Jose University, Leila Coyne, whose work has demonstrated how, if you strike a one-pound ball of clay with a hammer, it will glow ultraviolet light for a month! Light is energy. Whenever and however we touch clay - stroking, pinching, coiling or throwing - we are releasing energy. We may be too close to it to see it but we can sense it, with those delicate receptors that are so much a part of our nature. "The spirit is so close you can't see it," said Rumi, "but reach for it. Don't be a jar whose rim is always dry. Don't be a rider who rides all night and never senses the horse that is beneath him." Coming together, these two bits of information empowered each other, and me, into a new way of offering attentive presence to the clay; to entering, receiving and being with her. Whatever we touch is touching us.

There is a Japanese saying that has flowed into my life as a vital clue in recent years. When it appeared I trembled in recognition and felt myself being breathed into. "Art is the tracks," the saying goes, "not the animal." I take this to mean that works of art are visible clues, embodied evidence of invisible experience, but they are not the animal. The artist as animal? I go to the dictionary to search for the etymological roots of 'animal' and find two: animals for living; and anima for soul. The artist as animal as living soul? Behaving in an invisible realm? Leaving tracks, signs of the story of soul's journey of survival, her longing for nourishment, her need to uncover, to reveal, the beauty she discovers? I take these questions literally, a dialogue between body and soul that would re-imagine our animal being within our human being.

I am and have been helped in this inquiry by two beloved dancer friends, June Eckman and Remy Charlip who, in midlife, began to speak to me of a 'thinking body' and to study and become inspired teachers of the Alexander Technique, a body-awareness modality that releases the downward pressures of gravity, habit, collapse and negativity to free the body's natural levity, its heliotropism, to lengthen and widen our bodies into a subtle lightness of being - our animal being. From a habitual unconscious use of our bodies to a dawning consciousness of just how we are using ourselves in life's activities and being-ness. The search for freedom, for release, inside our bodies: our bodies, our bit of being, our microcosmic orbit within the macrocosmic orbit of energy breathing into us. Listen for it. Each of us lives in a house much vaster on the inside than it appears on the outside.

During one memorable Alexander lesson that I had in Seattle in the early 1980s, the teacher, Marjorie Nelson, stood next to me and put her knowing hands on my shoulders. "Don't just do something. Stand there," she said. Baffled by this, I asked her to repeat what she had said and then asked her who said it. "I did," she replied, "and the Buddha." Don't just do something. Stand there. Don't just do, be there. That lesson continues to echo in my body, reminding me how to be more fully alive. Standing, like sitting, walking and lying, becomes a delicate inner dance of present being. Remy calls them 'Dances anybody can do': a dance in a bed; in a doorway; with a red towel; pinching clay, pounding metal or plaiting fiber. All the craft-arts are movement-arts.

Working with both the Alexander Technique and clay inevitably led me to further study of life energies: how to move easefully and harmoniously in participatory consciousness with them. For several years now I have been studying 'Qigong,' (che-kunh). Qigong is said to have originated in the mineral, plant and animal communications of ancient Chinese Shaman who stood at the 'crossing point' between human and more-than-human being, pointing out to us, in movement and breathing patterns, how to allow landscape to permeate and heal our Inscape. This is where deep ecology begins for me: in the body. Where anima, soul and anima mundi, the soul of the world, know each other and energies revitalize. In our bodies and our clay bodies - lip, neck, shoulder, belly, foot - "Always, we are eating and drinking earth's body, making her dishes," M.C. reminded us. I experience Qigong as somatic 'Deep Ecology,'

a first step toward repairing the break between human and more-than-human being.

Qigong is not therapy or medicine or exercise to relieve symptoms. It is healing in its deepest personal/transpersonal whole-systems sense. It's meditation in motion, an art: one cultivates Qi as a way of communication with the life force that breath carries, the breath within breath.

Eight years ago, a book a friend shared with me initiated my committed ongoing practice. Slowly and steadily it has spread throughout my life and into my craft-art practices and way of being in the world. This is why I believe that the craft-arts are especially important in our troubled time. As a species we have lost our senses for and our imaginations of wilderness and natural processes, and our world is suffering the consequences: from pollution to globalization and, ultimately, to the madness of terrorism. Can conscious encounter with primary materials be a reconnecting bridge, jumper cables that will help us reclaim our integral roles in the formative ecological forces of life? Art, which comes from the etymological root, 'to join,' to put things together is, by its nature, healing. Have we reduced the arts to nouns, to commodities, to the work of experts? Aren't the craft-arts essentially verbs, behaviors? Aren't behaving artistically and healing ongoing birthright of being, dances anybody can do to heal themselves and the world?

In 1991, after a workshop I gave at a university in Perth, West Australia, an aboriginal woman who had participated urged me and made arrangements for me to join her family on a walkabout along the coastline of the northern Kimberleys. We walked for five days on the broad paprika-colored sand beaches that run along the edge of the blue-green Indian Ocean. The first night as we sat around our campfire, I was astonished by the awesome number of stars in the sky, free of light pollution. Seeing my reaction, Paddy Roe, the elder of the family, had one of his sons translate the following for me: "You see those stars? They are working for you, with you. They are the campfires of the ancestors. They sit up there around their campfires just as we sit here. They look down. We look up. And we make eye contact."

During the last day I could be with them, I asked Paddy why aboriginal Australians have been making art since 'the first day,' sixty-some thousand years ago, and who or what taught them how? His reason was long and thoughtful. His son's condensed translation was brief and without the wonder I sensed in Paddy's voice. "We didn't have to learn," he began, "We made things when we were stones, bower birds, ghost crabs, so it was natural of us to do so. We make art as a way to tell the dream-time stories to the children, but the bigger reason is this: this earth that we come from, this mother, would not be as fruitful, as reproductive and as supportive as she is without our appreciation. She needs to feel our appreciation, it nourishes her. The purpose of art is to praise, thank and express our gratitude and wonder. We make art to sing up the earth."

During the last day I could be with them, I asked Paddy why aboriginal Australians have been making art since 'the first day,' sixty-some thousand years ago, and who or what taught them how? His reason was long and thoughtful. His son's condensed translation was brief and without the wonder I sensed in Paddy's voice. "We didn't have to learn," he began, "We made things when we were stones, bower birds, ghost crabs, so it was natural of us to do so. We make art as a way to tell the dream-time stories to the children, but the bigger reason is this: this earth that we come from, this mother, would not be as fruitful, as reproductive and as supportive as she is without our appreciation. She needs to feel our appreciation, it nourishes her. The purpose of art is to praise, thank and express our gratitude and wonder. We make art to sing up the earth."

When we awaken to our soul and its source, the soul of the world speaks to us, flows into us, and all forms can become language. When we cultivate the energies of life as they move through us, we begin to behold and to palpate those energies in the beings and doings of everyday life, its materials and what we create with them. Working with clay opens us to a deeper, lived, sense of ecology in which we participate imaginatively with the primary materials of life, joining us to the continuous, evolving creation. This is a fuller art, spiritual by nature, simultaneously R J personal and transpersonal. Thomas Moore, in a recent article in Resurgence Magazine, says: "We are either ecologists or we are lost souls."

I believe that the pathology that has brought about our environmental disconnect, our deracination from nature in process, is the same pathology that has brought us into this time of technological warfare. The crossing point between human and more than human being, between inscape and landscape has been cut, the vessel of communication shattered and the light scattered. James Hillman has said that the environmental crisis is a crisis of aesthetics. I don't think he means the aesthetics of graduate craft art programs as in 'ideas of beauty.' I would like to think he is suggesting aesthetics in its root meaning as in 'of the senses.' And not just the five sense model of Western science, but the fuller palette of the more than sixty senses of our evolutionary lives of cosmic, mineral, plant, animal, human and angelic being. Just as we are losing species of life on this planet, we have lost and are losing our senses. Literally and especially those senses that connect us in reciprocal relationship to the world of nature.

German psychologists say that children around the world are losing their sense of touch by one percent per year, due to the proliferation of passive entertainment, computers and disembodied education. But touch is our gift, the genius of craft, its guardian spirit!

When we put our hands on the primary materials of the craft arts with imagination and the sense of reciprocity, we are healing ourselves and the world. We can balance our now almost aggressive capacity for creativity with our awakening senses for receptivity. In this time of devouring consumerism and materialistic mindset, we craft artists have a mission. For it is more than beautiful, useful, expressive and expensive objects that we are making. It's the story of the Big Art, of our interrelationship with the mysteries of life and its formative forces that we could be telling. We could sing up the hand, what we touch and what touches us, sing up the feet and the ground, the clay ground that supports us. We could sing up soul's capacity to uncover and reveal the awesome beauty of the continuous creation, our original blessing. We could stand like a tree, between heaven and earth, repairing our next, healing the cup, each one of us in some small way.

These are some of my stories. Thank you for listening. I replace the pipe on its pillow and say, "So be it," and look forward to hear your "And..."