This spring, the windows of my new workspace will open for the first time. That moment will come after a winter of cold winds, pandemic adaptations, and hard work. The space is not large, but it is more than adequate. I'm an aging potter, and a recent move led to less clutter in a new space. Working here feels liberating and hopeful. Most importantly, I left my basement studio behind. Now, I have windows. Windows are almost always good, but when you hope to have more time for studio work, they become a special feature – one of architecture's most impressive gifts.

This spring, the windows of my new workspace will open for the first time. That moment will come after a winter of cold winds, pandemic adaptations, and hard work. The space is not large, but it is more than adequate. I'm an aging potter, and a recent move led to less clutter in a new space. Working here feels liberating and hopeful. Most importantly, I left my basement studio behind. Now, I have windows. Windows are almost always good, but when you hope to have more time for studio work, they become a special feature – one of architecture's most impressive gifts.

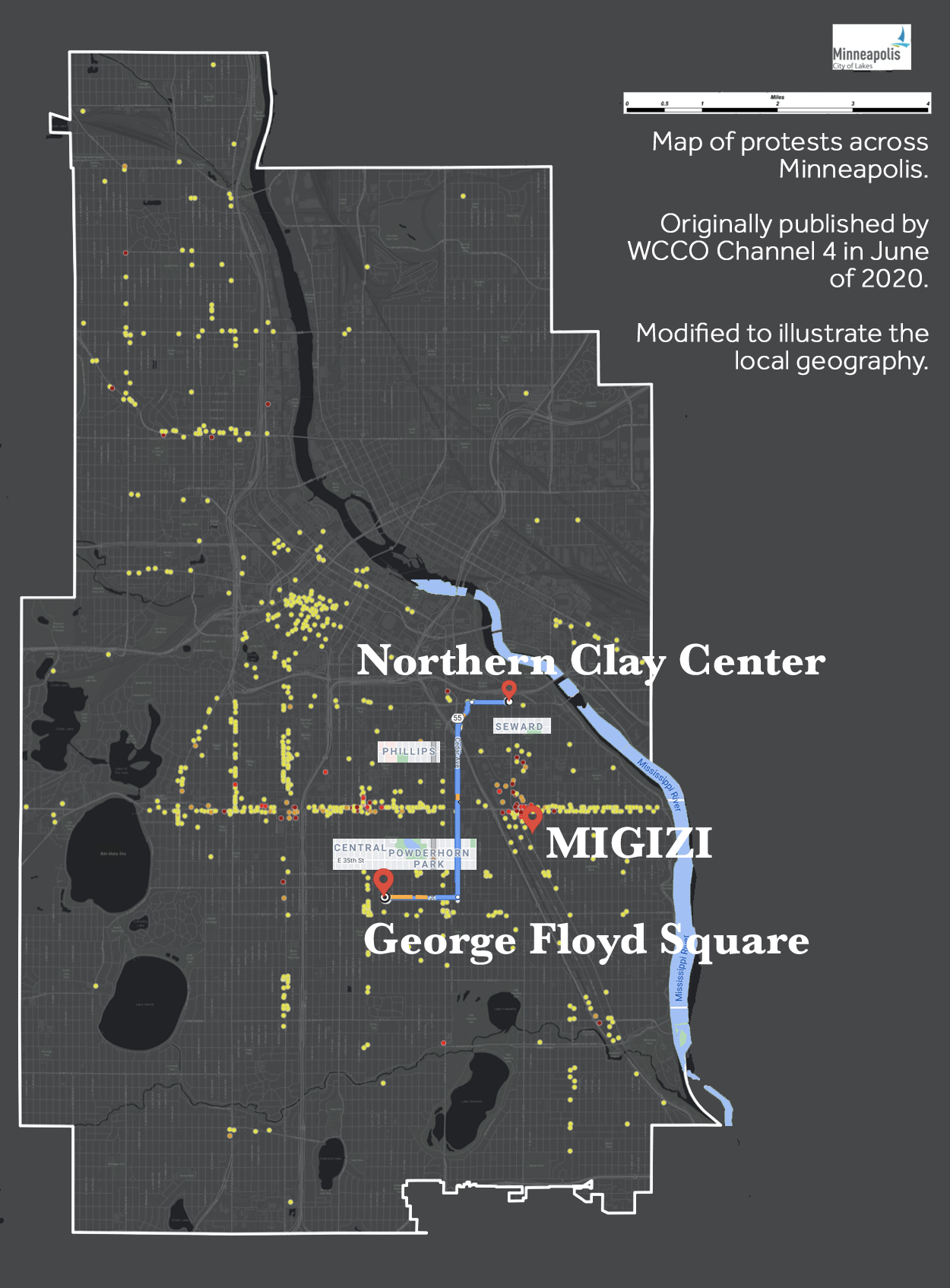

As I was remodeling the workspace and moving at the same time, there was a growing rebellion after the murder of George Floyd. My home is just over an hour away from Minneapolis, and I know the Minneapolis neighborhoods where Floyd was killed. Eight blocks to the north of what has become George Floyd Square is the Global Market – home to dozens of locally-owned, diverse businesses. It is just over two miles from Global Market to Northern Clay Center (NCC). I can drive from one to the other in ten minutes or so.

The neighborhoods are familiar to my partner and me. As teachers, every hour, every day immersed in this sort of diversity is a gift. That gift can always find a way back to the classroom, into the lives of students, and to our home community. Many are tired of the word diversity. For too many, it brings to mind ineffective workshops, repetitiveness, and the sound of established voices explaining things to us. That is why immersion works best. Let the neighborhoods talk. I have waited for someone to discuss the murder of George Floyd in the journals I read, and I have waited for substantive responses from the organizations and institutions we move within and between. But at some point, there needs to be a place for all of us to jump in. For me, this is that place.

The neighborhoods are familiar to my partner and me. As teachers, every hour, every day immersed in this sort of diversity is a gift. That gift can always find a way back to the classroom, into the lives of students, and to our home community. Many are tired of the word diversity. For too many, it brings to mind ineffective workshops, repetitiveness, and the sound of established voices explaining things to us. That is why immersion works best. Let the neighborhoods talk. I have waited for someone to discuss the murder of George Floyd in the journals I read, and I have waited for substantive responses from the organizations and institutions we move within and between. But at some point, there needs to be a place for all of us to jump in. For me, this is that place.

Phillips, Powderhorn, and Longfellow neighborhoods are clustered together in Minneapolis south of Interstate 94. Drive farther east into St. Paul, and you will pass through what used to be a vibrant Black community – the Rondo neighborhood. The decision to let I-94 cut through and destroy the Rondo business district during the late 1950s remains an unmistakable symbol of racism – many other American cities used the same tactic. The highways and streets of our nation are built and maintained on a racist foundation, and it shapes our neighborhoods.