Editor's note: See Vol. 13, No. 2, June 1985 for "Potters of the Blue Ridge Mountains" featuring several potters from this article.

I met Kevin Crowe twenty years ago on a canoe trip with some friends from work. Tye River Pottery lay between the put-in and the takeout, and my companions browbeat me into stopping when they saw his sign. Less than a year later, I found myself married to the man and immersed in the strange and wonderful world of clay and the people that spin mud into functional works of art.

Though not a potter myself, I was welcomed into the Nelson County clay community by potters Nan Rothwell and Trew and Tony Bennett – and into a whirlwind of raising kids, firing kilns, setting up shows, opening a gallery, hosting exhibitions, closing said gallery, building websites, and always, pots, pots, beautiful pots.

Turn around. Two decades are gone. Trew and Tony say they’re retired, but what do they mean? Nan is moving out of the county, and one of Kevin’s apprentices is setting up shop here. Kevin, too, is changing his game. I decided to visit each of the potters, starting at the north end of the county and working my way back home, to see what’s really going on in Nelson County.

“We’re retired now,” Trew says. She and Tony sip from tea bowls of herbal tea as they walk me through their studio at Buck Creek Pottery. The lines of Tony’s exquisite slab-built vases evoke the sleek curve of a fish here, the swoop of a woman’s hip there. His smooth bowls tell the story of millennia of rushing water that shaped the large river rocks which served as their slump molds. I hold an ear to one of Trew’s wheel-thrown forms and hear the whisper of ancient tradition. Pots await the gold dust that she will use to fill the cracks, according to the kintsukuroi practice she adopted as a young potter. Nothing about this studio says retirement.

In the 1960s, Trew studied at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. with Malcolm Wright and his teacher, Teruo Hara. There she began to see a life in pottery. “It was very important to us that you could start with clay and mix it and wedge and make pots, and then bisque it and glaze it and fire it,” Trew says. “You were a part of the whole process – you didn’t turn anything over to anyone else.”

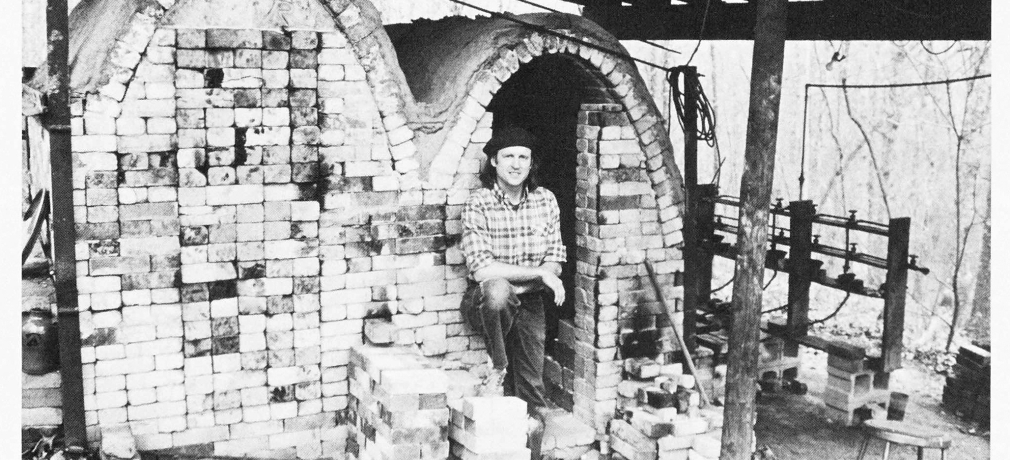

The first time Tony met Trew, she was firing a wood kiln. “The charcoal, the sweat, the wood, the gloves,” he says, “This woman was a worker!” After forty-five years of marriage, they do not complete each other’s sentences. Rather, each regards the other with rapt attention, certain that something fascinating and unexpected is about to emerge.

“You were cutting through those logs like they were butter,” Trew gazes at him, still impressed. “And I thought, ‘Oh, this is a great guy!’"

... Share

Share