Time, Place, and Taste of Clay

If one thinks of time as moving forward and backward, then place might be thought of as a move in a lateral direction or from left to right; from side to side. The artist, doing significant work, is affected in his or her work by both these notions of location. The ceramic artist is also affected by the earthen material we call clay.

RETURN TO JAPAN

The station where we were to catch the bus to Shigaraki was as noisy and confusing as I had remembered it. Station masters still blew their whistles directing bus drivers as they backed their awkward vehicles into position to load the passengers. It was May 1991. My wife Susanne and I were returning to the Japanese pottery village of Shigaraki where we had once worked for a year in a tradition of pottery making that has survived for seven hundred years. As two uninitiated but eager foreigners, we were taken into the lives of these people in rural Japan almost twenty-nine years ago.

On board the warm, half-loaded bus, we now began the last leg of our journey across the once familiar countryside. I was travel weary and, even though the roads were now paved and the buses more modern, it was not long before my thoughts were picked up by the nostalgia of the trip, and I was back in 1962.

I remember those early years as instructor of ceramics at the University of Michigan when I became eligible to apply for a University-funded Rackham Grant. I received the faculty research grant, and Susanne and I set out with a new sense of excitement and adventure. Our plan was to meet Marie Woo in Tokyo. Marie, who had been the instructor at Michigan before me, had been working in Japan for three years. My mind flashed back to the photographs she had sent back of Japanese hill-climbing kilns and of pottery marked by the lick of the flame in the wood-fired kilns. I remembered the books of Isamu Noguchi's playful clay sketches done in Kaneshige's Bizen kilns. Bernard Leach, the Englishman who had worked in Japan alongside mingei potter Hamada Shoji, had also filled my thinking about Japan when he did a workshop in Ann Arbor in 1959. Kaneshige Michiaki, son of the Bizen master, had stayed with us for a few days in Ann Arbor.

The influence of Japanese ceramics on the clay artists of the United States had been considerable. Hamada and Leach had given workshops as they traveled throughout the United States in the 1950s. Kaneshige and Kato had also made tours. A number of years after our return from Japan, it would be my turn to host Hamada for a week at Ann Arbor. He was part of a celebration during which he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Michigan in 1969.

A TASTE OF CLAY

It was Kaneshige Toyo, the Japanese National Cultural Treasure from Bizen, who said that if he were going to set up a pottery studio in the United States, he wou Id go arou nd and taste the local clay. The site would be selected based on his idea of how the finest clay should taste. This was a very Japanese idea, because potters have traditionally used clay mined in the vicinity of the kiln site. The idea of tasting clay intrigued me. In this country clay is trucked in, and a blend is custom made from materials from different parts of the country and even abroad. In this country tests are made of clay bodies, but few ceramists make the taste test. In Japan the potter's work carries the characteristics of the local clay. Fine smooth clays tend to be more plastic and tool easily. Coarse clays tend to be less plastic and can be difficult to tool. In English the double meaning of the word "taste" intrigued me, because it involves testing with both the tongue and the eye. For that reason slide lectures which I have given on Japanese ceramics have often been entitled, "A Taste of Clay."

When I arrived in Shigaraki in 1962, most of what I saw did not bear a resemblance to the early pottery I was searching for in Japan. To find examples of pottery with a black scorched side and the chunks of feldspar sweating to the surface, one had to ask to see it. At Rakusai's where we worked, they were making ceramics which was glazed ware to be used for flower arranging.

Most other potters in the village seemed to be making cobalt blue hibachi, the Japanese stove, formed inside a plaster mold. Rakusai had retired from the making of these flower arranging pieces so he could devote himself to natural fired work. This was work where the flame and the varied wood ash deposits controlled the surface of the pot.

The first clay we were given in the pottery was smooth and had none of the character which we were seeking. Where would we get the chunks of feldspar and flint, we asked. A hand pointed to the ground. There it was, alI over the place. Later we took our Honda motorcycle up the road to feldspar mountain. There you could take a small rock of feldspar the size of a cobble stone and twist it between your hands, and it would break into pieces just about the right size. Every day was a new adventure—something new to learn about the language, the customs and ceramics. In the early 1960s I was not yet aware of time and place having an impact on me as an artist.

John Chappell, an Englishman we met in Kyoto, helped us arrange to work in the workshop of Takahashi Rakusai which was at the edge of the village. He also arranged for us to stay at a local inn run by the Naomura family. The Naomura family took care of our daily practical needs and at the same time taught us Japanese customs.

My mind has often picked up the misty view from our room at the inn looking out over the rice fields toward the distant train station backed by mountains.

Change had marked the intervening years. Just how much had Shigaraki changed since we had see it last? I expected some marked change because I had seen photographs of the ceramic sculpture park. The park presented a modern type of architecture that was already in contradiction to the thatched and tiled roofs of the traditional Shigaraki architecture.

Actually, the ceramic park was the occasion for our returning to Shigaraki. We were part of a group of ceramic artists from Michigan participating in a month-long symposium that was to showcase the new facilities in Shigaraki. We were there to work in the clay and interact with potters of the village. As the bus rolled into the village, I sat up in my seat to begin the first of a continuing series of "place and time"adjustments.

Where rice had once been harvested, now there were long stretches of black asphalt parking lots. They were for use by automobiles and buses coming to what the large banners proclaimed as "Ceramic World". A flourishing Japan had buried the quiet village I had been introduced to years earlier. Bull horns directed crowds of people and police whistles stopped traffic. The village had outgrown the rice fields. It would not be an easy task to find the inn where we had once stayed. It would take a few days before I could begin to re-establish significant connections with the Shigaraki of the past.

It was not really necessary to find the inn right away. We were in good hands. A homestay with the potter Suzuki and his family had been arranged. Later we would stay in the tea house of the new generation of Takahashi Rakusai. The eldest son had taken on his father's name as his father had done before him.

Actually, the Suzuki family live further along the valley somewhat apart from the village but still a part of what Louise Cort entitles her book, Shigaraki, Potters' Valley. What had once been a compact pottery village is now a ceramic community spaced broadly about the valley Thirty years ago the potters of Kyoto did not want to be associated with Shigaraki because it was a commercial center for hibachi and garden furniture production.

The smoky kilns of Kyoto were finally closed down and the potters had to move to Shigaraki if they wanted to fire with wood. Today, ceramics is pursued in Shigaraki on almost every aesthetic level. There is a new concern for the supply of clay in the area. Some of the clay sources, we were told, are now located under new golf courses in the area.

The clay artists from Michigan, Susan Crowell, Marge Levy, Mary Roehm, Tom Phardel, Sharon Que, Doug Kaigler, Kathy Damback, Marie Woo, Georgette Zirbes, Susanne and I, worked at Ceramic World for almost two weeks in front of thousands of park visitors. Attendance at the park averaged 50,000 people a day. Then the news came of the tragic train wreck. A train loaded with passengers coming to Ceramic World collided head-on with another smaller train just outside Shigaraki. Over forty people were killed and four hundred injured. It was the worst train accident in Japan in fifty years, and said to be the combined result of human and computer equipment failure. The tragedy resulted in the immediate closing of Ceramic World.

A DIFFERENT TIME, DIFFERENT PLACE

One benefit of studying in Japan in the early 1960s was that it gave me a clearer understanding of my own culture. I could not be an American working in a Japanese style, living in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Being in Japan demonstrated how the environment enters the artist’s work, that we are not the independent, free spirits we would like to think we are, but rather what we create visually is impacted on by a range of influences that are not necessarily art related. It is paradoxical that at the same time the artist also brings along considerable

aesthetic "baggage" which is tried on by the artist and paraded in front of the mirror. The baggage may take on a new meaning or significance in a new place, or it may be ultimately rejected as inappropriate for this, a new time or place. The experience of working in a different place and at a different time helps to cut through to the core of the artist inside.

In Japan there were many ways of handling clay and the ceramic process that had been passed down from generation to generation. There were different ways of kneading clay, making clay slabs and throwing on the wheel. These were stimulating to the process and often influenced the final appearance of the object. A potter's wheel could be operated clockwise as well as counter-clockwise. Forming work from clay tends to encourage the use of a wide range of techniques, as does the entire ceramic process for that matter. Every pottery village seemed to reveal techniques unique to its handling of the medium. I still take delight in seeing how someone else handles the process.

While working in Shigaraki, where clay slabs were worked into plaster molds to form vessels for flower arranging, I hit upon the understanding that the slab didn't need to be worked to conform to the shape intended by the mold. If negative areas were allowed to develop, the mold could be used solely to secure the seams to make the piece hold together. Each piece coming from the mold could actually be unique instead of identical as a mold is generally intended. Today, it is difficult to believe that in the 1960s plaster molds were not acceptable for serious studio potters.

I worked with this approach when I returned to the United States, but at that time I started using newspaper impressions in the clay slabs. I was able to make a readable newspaper impression casting sculptor's wax in the cardboard matts used on the presses and working black glaze into the surface like an intaglio plate in the biscuit state. The news articles at the time dealt with Viet Nam and racial riots. It was not a time to be lyrical. In working with this series of newspaper impressed pieces I related strongly to the statement made at least a decade earlier by the Japanese potter Kawai Kanjiro, who was said to have commented, and I paraphrase, "Everything I make is not beautiful. There is also something ugly inside that must be expressed."

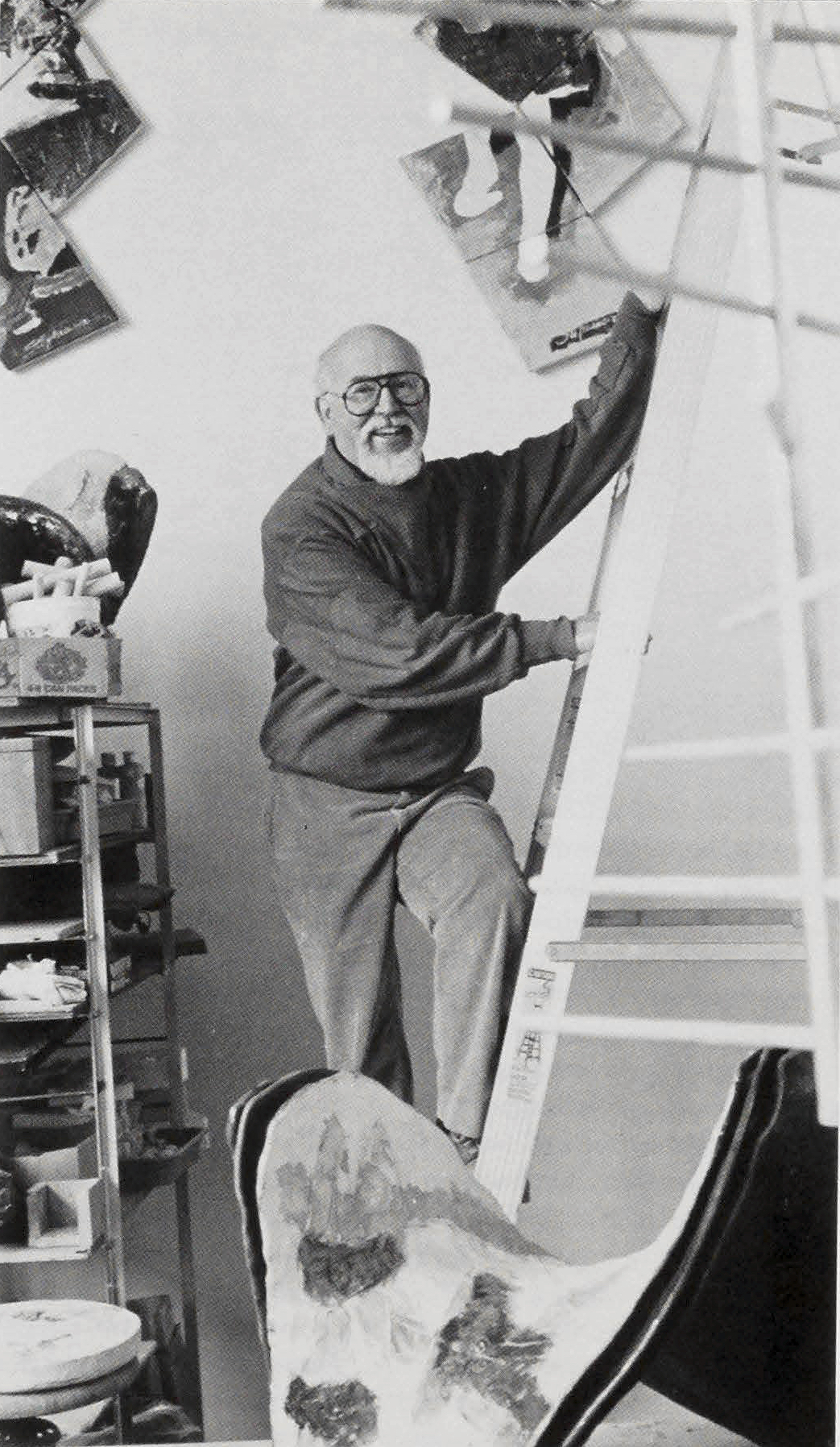

In the 1970s I moved into other media and into mixed media. I wanted to experience large scale, so I worked in steel and aluminum, materials and techniques new to me. I learned how to weld. I also held onto a concept from Japan about hard and soft form as I started a series of mixed media wall constructions. In clay, I developed the soft forms that were contrasted against the hard forms developed in grids of wood or grids of aluminum extrusions.

Clay was the flesh and wood or aluminum the bones of the work. There also seemed to be an urgency for me to make work to be viewed on the wall, or on the floor under foot.

By the 1980s, the things I had learned from my mixed media experience moved into the process itself. I used wood and metal in the forming process, but the final result of the process was solely from fired clay. I was attracted to the auger as a dynamic form that energizes space, but also to the metaphor that exists between the auger that moves clay and a clay auger as a ceramic form. The auger has a visual push and pull, into and out of the axis of the form.

The auger brings to three-dimensions the visual energies of the familiar two-dimensional spiral. In order to build the form in clay, I used aluminum pipe for the axle and aluminum rod for describing the twist or torque in the form.

A TIME AND PLACE FOR FURTHER TASTING THE CLAY

Certainly, we all recognize the cultural dialogue going on between Japan and America. It is not a passive relationship. There is a visual conversation going on in the clay that can be more fully understood and appreciated if we compare it metaphorically with the workings of the wood saw. The Japanese saw is pulled, and the American saw is pushed, and in knowing hands beautiful wooden structures that lift the spirit of mankind are made with both tools. While the aesthetic concerns pursued by artists of both countries move in different directions, in clay they share in their ability to hold significant meaning in contemporary culture.