Téranga - The Art of Welcoming

As an editor, it is my pleasure to introduce you to and welcome the talented ceramic designer Faty Ly. Faty is the designer and founder of the brand FATYLY; as part of its mission, the brand contributes to the preservation of African cultures as a heritage that will be anchored in the collective memory of future generations. Faty holds a master’s degree in design management from the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design. She is currently a board member of Africa Design School in Benin, West Africa, and has established herself as a prominent figure in the world of ceramic design. Faty has been featured in Design Diffusion - an online magazine spreading design news and culture – and the Fields Magazine's "Design Issue," among others. Beyond her ceramic career, Faty has collaborated with chocolatiers and chefs for the promotion of Senegalese culinary heritage, in particular with "Mind of a Chef" in Food & Wine magazine. She is also a founding member of Afroeats, a festival of African cuisine and local food products.

As an editor, it is my pleasure to introduce you to and welcome the talented ceramic designer Faty Ly. Faty is the designer and founder of the brand FATYLY; as part of its mission, the brand contributes to the preservation of African cultures as a heritage that will be anchored in the collective memory of future generations. Faty holds a master’s degree in design management from the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design. She is currently a board member of Africa Design School in Benin, West Africa, and has established herself as a prominent figure in the world of ceramic design. Faty has been featured in Design Diffusion - an online magazine spreading design news and culture – and the Fields Magazine's "Design Issue," among others. Beyond her ceramic career, Faty has collaborated with chocolatiers and chefs for the promotion of Senegalese culinary heritage, in particular with "Mind of a Chef" in Food & Wine magazine. She is also a founding member of Afroeats, a festival of African cuisine and local food products.

Faty's work is characterized by the highest standards in craftsmanship and savoir-faire (inherent knowing or intuition) for the design of lifestyle products inspired by African cultures. Her designs often draw inspiration from the Senegalese visual culture, combining elegance, luxury, and functionality in her creations. She embraces the rich heritage of ceramic art and Senegalese culture while infusing her designs with a modern sensibility.

Randi O'Brien (ROB): Tell me a bit about where you are from. Are the region and culture rich with art, crafts, and design?

Faty Ly (FL): I am from Senegal, and I was born in Dakar, a peninsula historically called presqu’île du Cap-Vert. On my father’s side, my family has its roots in Mali and Mauritania. Dakar is the capital of Senegal, bordered by four African countries and located at the westernmost point of Africa in the Atlantic Ocean, thus making the country close to the Caribbean, Brazil, and the United States.

Senegal has a widespread Wolof culture that has shaped who we are as people. It is home to a variety of cultures and languages, which makes Senegal a crossroads for encounters between different cultures. The country is known for its téranga (the art of welcoming) and its masla (the art of living peacefully across and within communities and a capacity to tolerate that we vehemently blame from time to time as undermining our relationships with one another). Senegalese people are also known for their traditional values, such as kersa (a lifestyle based on restraint). We also value courage and resilience, known as mouñ in the Wolof language.

Senegal and Dakar, in particular, have taken a leading role in art since 1960 on the African continent and have more recently established themselves in design and craftsmanship. Dakar is famous on the continent for its Contemporary African Art Biennale, Dak’Art, which celebrated its fourteenth edition in 2022. The city of Dakar has become a site for private exhibition spaces such as art galleries and public spaces for art, such as the Museum for Black Civilizations (MCN, known in French as the Musée des Civilisations Noires) and its Grand Théâtre dedicated to performances. Dakar Fashion Week is a landmark event, and we have a handful of concept stores to showcase design and craft. More recently, the Saint-Louis Photography Museum (MuPho), the first museum in Senegal dedicated to photography, opened its doors in the north of the country in Saint-Louis.

ROB: Can you describe your tableware motifs? What are the images, and where do they derive from? Why are they important to you and your community?

FL: The motifs on the Fatyly tableware derive from black and white studio portraiture from the 1940s and 1950s in Senegal. Most of these inspiring photographers were born in the northern part of the country, where West African portraiture is said to have been born in Saint-Louis, Senegal. These prominent photographers highlighted Senegalese women's lifestyles during those times.

As a child, I recall women decorating walls in bedrooms and living rooms with their black-and-white photographs. As far as I can remember, I have always been fascinated by the details in these photographs, as I was drawn to the traditional women's hairstyles and attire. In my family, women used to call hairdressers at home and have sophisticated hairstyles made for them; they wore the finest jewelry from head to toe. I vividly remember seeing my great-grandmother and grandmother dressing up for special occasions; photography sessions were one of them, and as a result, I was naturally drawn to these photographs. These portraits depict women with imposing and elaborate hairstyles. One has to know that hairstyles were not only a symbol of social status but also a means to express political views back then. Women also overlaid around their hips woven wraps known as sërou Ndenk* in the Wolof language. These garments are heirloom wraps; they are today modernized and used in fashion and interior design, but back then, they were designed for protection, honor, aesthetics, and sentimental value.

The elegant yet imposing fashion style depicted in these photographs is also a sign of power and independence for traditional Senegalese women. Both gold jewelry and woven wraps were objects of and for women's savings. I have used gold on my "Nguka" plates to reminisce about their gold jewelry. Beyond wearing gold jewelry as a personal adornment for the body and hairstyle, Senegalese women have always cherished gold as a means to maintain financial independence.

I believe craftspeople, designers, and artists are nostalgic about these black-and-white portraits. I also think these portraits reminisce about a period of time when people were comfortable in their skin and where beliefs and values had significance in people's lives.

ROB: Is it common to see tableware with Senegalese portraits, or is this a design that was intentionally chosen to fill the gaps within that visual culture?

FL: It is common to see Senegalese portraiture on glass and, more recently, on tableware. Senegalese portraiture has always been a source of inspiration for many craftspeople and artists. The technique of underglass painting known as souwere is a Senegalese tradition where the subjects are very often represented in a dignified manner. Souwer craftspeople have composed portraits with vivid colors and golden touches to represent women and couples in traditional garments. I was drawn to porcelain as a canvas to somehow perpetuate the Senegalese recording of appearance in an unexpected way by using printing techniques with a more minimalistic color scheme.

ROB: The surface of your tableware is beautifully designed and hand-drawn by you. Do you source the tableware from external suppliers? Do you send your design out to be printed by the manufacturer? How does that process work?

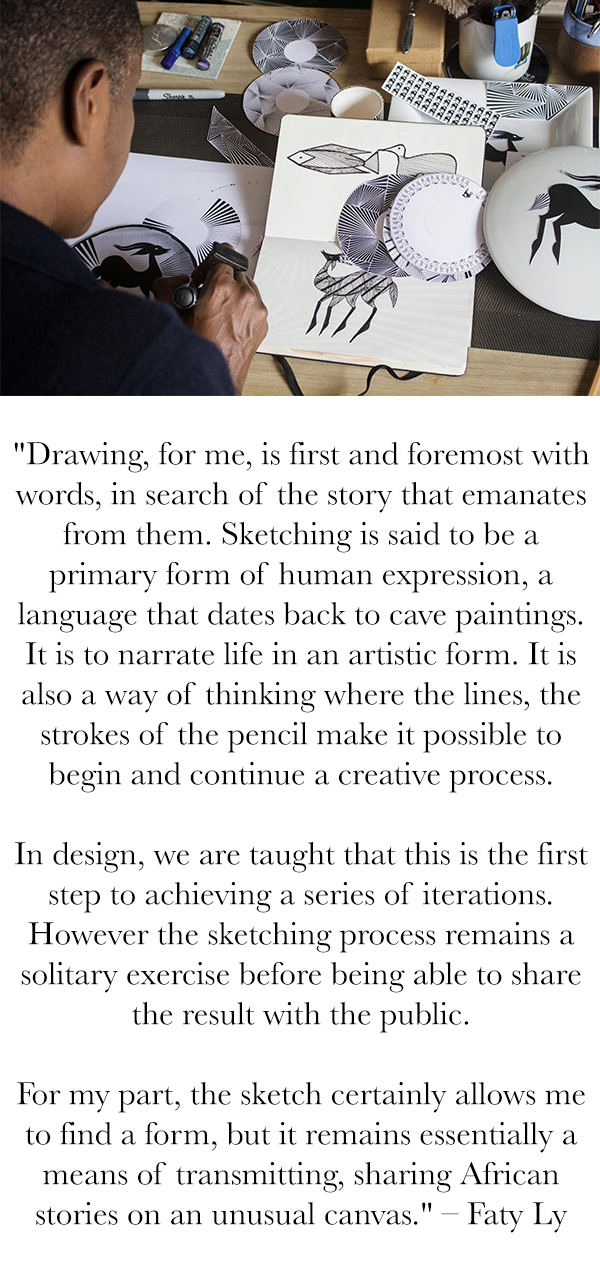

FL: I draw and make maquettes in my Dakar studio by applying printed motifs to plates and cups to project on the final surface. Then I leave the rest to the manufacturer, who applies transfers to porcelain forms and produces the tableware. I work with manufacturers in Limoges, France. I have also collaborated in the past with manufacturers in Portugal and Stoke-on-Trent, England.

ROB: I see that you also have handmade vessels with pressed, textured coils applied to the pots’ surface to mimic traditional woven fabrics or hair strands. Can you describe why these textures are important and your decision to use those surfaces?

FL: If one takes a close look at my first series, "Nguka," one will see horn-like forms on the women’s heads that reminisce about a traditional hairstyle. That was, for me, my first attempt to represent black hair in my work. By using textured coils, I was able to get close to the look of black hair strands and our traditional woven fabrics. Traditionally, cotton thread coils were used by craftsmen to weave cotton wraps embellished by twisted edges. That same twist technique is probably one of the oldest hairstyle techniques that Senegalese women have used in the past and still use to this day. Therefore, it was important for me to be able to achieve a three-dimensional effect; hence, using clay is more illustrative of the texture of our hair and fabrics.

ROB: How have you experienced the contrast between the industrial side of tableware and the handmade side of original work, like your pressed and textured coil vessels?

ROB: How have you experienced the contrast between the industrial side of tableware and the handmade side of original work, like your pressed and textured coil vessels?

FL: The experience was challenging, as I am used to refining finishes with porcelain materials and was initially trained in an industrial environment. As a designer and maker today, my main challenge resides in using a non-formulated body of clay to make textured, pressed coils. Because the harvested local clay is overly plastic, it is time-consuming to form shapes, apply surface decor or texture, and dry the work. But at the same time, it is very satisfying to overcome the plasticity of the clay and produce the body of work I am producing today.

ROB: Do you see these hand-built coiled forms as individual works of art, or do you see them as a body of work within your ceramic design ware, like the high-end tableware?

FL: That is an endless debate. I am currently making my living as a designer, and because of this, I am naturally drawn to the function of objects. I consider design an approach that needs and includes art. Many of my projects started as works of art that evoked the dynamism of African narratives. My creative process and the development of the projects have made me answer people's needs, such as tableware that tells their stories. The future will tell where I fit the most, but so far, I see these hand-built coiled forms as a crafted form, a means of expression in order to imbue objects and utilitarian objects with significance.

ROB: Why did you choose ceramics and/or tableware to be the canvas for transmitting and sharing African stories? What is special about ceramics for this purpose?

FL: Ceramics appeared in the Neolithic period across continents and served multiple uses, from housing to vessels. As a versatile material, it has been found on many archeological sites, enabling one to find out about people and their lives, hence tracing people's stories around the world. To this day, ceramics continue to tell stories, and they are invested in by craftsmen, designers, and artists who remain attached to their materiality and surfaceness. Ceramics is still a material of choice in the art world, from sculpture to sgraffito; therefore, for me, porcelain surfaces and ceramic materials enable me to witness Senegalese or Ivorian stories and share their traditions with the rest of the world.

ROB: I get the sense that luxury is one of the key conceptual elements of your work – visually celebrating the textures, fabrics, and images that are synonymous with luxury. In the photographs on your website, the place settings are paired with rich cocoa, tea and tea leaves, and savory desserts; aesthetically, the work has elements of heritage and is seamlessly paired with the crisp craftsmanship of the surface decoration; the work and advertisements have an air of exclusivity with a hip or modern social scene. All of these traits create the conditions for me to want to buy into your brand. With your academic background in design management and your entrepreneurial career, how do you balance the idea of luxury with the idea of access? Do you have a different perspective on this for your coiled forms? Ultimately, the heart of what I'm trying to explore is: as a designer, do you have a different perspective on marketability and sales for your tableware than for your coiled forms? Do you have any advice for emerging designers and artisans?

FL: Crafting the luxury experience is indeed an element of my work. The Fatyly brand has launched renowned lines such as Nguka or Toile de Korogho to emanate uniqueness and exclusivity when compared to tableware found in the market. The business wants to keep exclusivity, which is why, as a designer, I am slow at adopting e-commerce to reach more customers. So far, low volumes of Nguka and Toile de Korogho are sold on the continent due to high taxes on imports. Because one has to sell in order to survive, I am thinking of going online to sell both locally-made tableware and my coiled pieces, thus making some products more accessible. The business wishes to target a larger audience; therefore, making a great shift to e-commerce and social media marketing will enable the business to grow. However, Fatyly's online presence has a double-edged sword. We live in a world where we have to remain visible to create brand awareness, but at the same time, the brand has to keep its exclusivity in order to build the brand’s credibility within the high-end marketplace. Reaching the age of online sales will enable the brand to somehow give access to its consumers with more product offerings, hence the production of local handmade tableware and coiled products. For the brand to maintain that element of exclusivity, we will have to continue to propose quality products while allowing customers to have the same experience with the porcelain tableware.

FL: Crafting the luxury experience is indeed an element of my work. The Fatyly brand has launched renowned lines such as Nguka or Toile de Korogho to emanate uniqueness and exclusivity when compared to tableware found in the market. The business wants to keep exclusivity, which is why, as a designer, I am slow at adopting e-commerce to reach more customers. So far, low volumes of Nguka and Toile de Korogho are sold on the continent due to high taxes on imports. Because one has to sell in order to survive, I am thinking of going online to sell both locally-made tableware and my coiled pieces, thus making some products more accessible. The business wishes to target a larger audience; therefore, making a great shift to e-commerce and social media marketing will enable the business to grow. However, Fatyly's online presence has a double-edged sword. We live in a world where we have to remain visible to create brand awareness, but at the same time, the brand has to keep its exclusivity in order to build the brand’s credibility within the high-end marketplace. Reaching the age of online sales will enable the brand to somehow give access to its consumers with more product offerings, hence the production of local handmade tableware and coiled products. For the brand to maintain that element of exclusivity, we will have to continue to propose quality products while allowing customers to have the same experience with the porcelain tableware.

Today, we all live in a world where products are made to be disposable, but it takes time to build a brand. For Fatyly, craftsmanship is important; it is the quality of the products and the attention to detail that differentiates the brand from other brands. Like many crafts, the work of clay requires patience, resilience, dedication, and continuous refinement. Therefore, for any designer or artisan, I would advise having a love for well-made products, which means products that are made with passion and care.

ROB: Is there anything that our readers should be aware of within the ceramics community that is important to you?

FL: Whether it is tableware or coiled, textured pots, my work is about contributing to the collective memory. I also understand that not all shared memories are collective memories. Collective memories are also selective; I trust that distilling less familiar stories and less familiar material can trigger cultural exchanges, and social interactions, shift paradigms, and eventually create a convergence between people.