The Spirit of Chinese Pottery

This beginning led me to investigate many other old and contemporary pottery kilns. I became aware of the Chinese pottery villages struggling to survive because there is now little demand for traditional pottery. The potters' lives have been transformed by their migration to the cities in search of a livelihood. Spurred by the global economy, China is dashing headlong into modernization and industrialization, leaving behind its rich cultural heritage in arts and crafts and architecture. In urban centers, whole old neighborhoods of traditional courtyard houses have been demolished and replaced by highrise structures, and ancient city walls with their magnificent gates have been destroyed to make way for highways.

Peoples' lives have been disrupted, and the rich character of beautiful old cities such as Beijing has been obliterated. Until recently, remote rural villages. were protected by distance from these fast-paced changes.

Unlike the sophisticated porcelains and fine imperial court ceramics, which are admired and collected by museums and widely documented, Chinese peasant pottery is relatively unrecognized. The Asian Cultural Council, a Rockefeller affiliate, provided the initial support for my travels to investigate and document folk pottery in China, a quest that became a complex journey into the unknown. China is geographically vast and diverse. The challenge has been daunting and often overwhelming, but the experience has been compelling, inspiring, and always stimulating. I have traveled ten years and many miles across China documenting contemporary folk pottery. I usually traveled with Li Jiansheng, an artist friend who is resourceful and knowledgeable about "all things Chinese." He helped me plan itineraries and arranged for a small bus to fit a group of Michigan potters who were enthusiastic supporters of the project. Sometimes it was a challenge to reach remote destinations, and there were times we had to hike the last mile up steep narrow paths because our driver refused to take the bus any farther. Once we were rescued by a bulldozer that pulled our vehicle out of the deep red mud that covered the wheels.

Peoples' folk art is the essence of Chinese expression. In pottery, the long journey from the bold neolithic Yangshou painted pots to the present-day utilitarian village pots is an awesome historical achievement. I have great admiration for the diversity and richness of creativity that so fascinates me. The amazing celadons, the humble tenmoku bowls, and the spontaneous Cizhou stoneware captivate me.

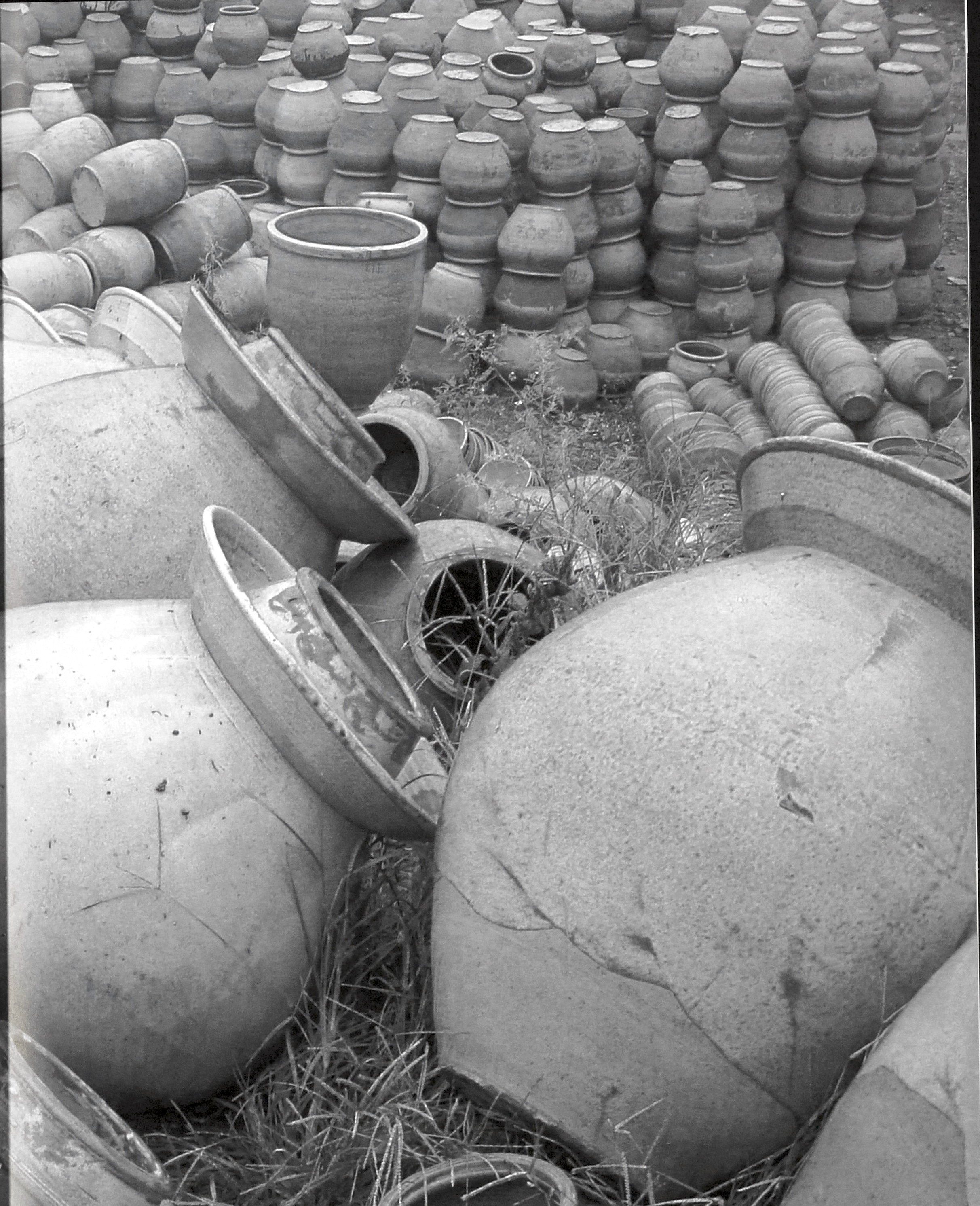

It is a welcoming sight to visit villages that are still producing needed pots, such as pickle jars whose double rim, filled with water and covered with an inverted bowl, becomes airtight. Huge wine and water containers, usually covered with brown slip glaze, are still produced all over China, as are bricks and roof tiles fired in the "water reduction" method that has been used for 50 centuries. This involves a shallow pool for water on top of the beehive kiln, which allows water to seep through the kiln walls when the firing temperature is reached (H20 + C = CO + H2). The water in combination with the carbon creates the reducing atmosphere responsible for the ubiquitous gray bricks and tiles seen all over China!

I have been asked: How has your China experience affected your work? The essence of a foreign culture and its art always requires time for me to process, and I have not yet detected any direct or immediate effect. By contrast, my earlier experience with Asian culture, in Japan in the sixties, was very different. It was a stunning discovery and exploration for a receptive, innocent foreigner not too many years out of graduate school. When Toyo Kaneshige, a potter who was a Japanese Living National Treasure, came to Michigan in 1960, he demonstrated with a relaxed attitude and sensitivity to the clay that captivated me and my students. We learned about wood firing and unglazed surfaces as well as about the organic conception of clay. When he invited me to Japan I did not hesitate. It was a splendid opportunity to work in Bizen, an ancient pottery village where time stood still. I was totally immersed in the world of an exotic culture offering a unique pottery tradition and a clay vocabulary that I was eager to accept.

Having digested this first Asian experience, I think I have now established a mature perception, ripened by decades of work. My recent China experience has been immense, and the influences seem elusive, but with the flow of time an unconscious expression may prevail. It is the culmination of years of rejected and accepted experiments that defines my work.