The Space of Pottery

The ideas I want to discuss here come from many sources but most importantly from my reactions to two articles I recently read. The first is Toronto art critic John Bentley Mays' "Comment" in American Craft (Dec.'85/Jan.'86; pp. 38-39) where he justifies his reasons for ignoring crafts: "not because craft or craft-as-art (as I have experienced it) are inferior to art, but because they are not art." This kind of commentary truly aggravates me since it is really too easy to simply state that craft is not art without expanding on what it actually is. That’s a cheap cop-out. The other article is by French thinker Michel Foucault and it deals with certain aspects of contemporary space. Hence these reflections on "the space of pottery."

The element common to all art forms is space. After all, painting is the investigation of bi-dimensional space; sculpture of the tri-dimensional; architecture, the space we live in; music, the space between sound and . . . silence; dance, the space of stillness and movement. If space is common to all art forms, it is also the different ways they deal with space that set them apart from one another.

What then is the space of pottery?

I am talking here of pottery in its simplest essential form. For example, an ordinary white bowl. By "pot" I do not mean simply an object of containment in clay (or in wood, metal, paper, etc.) but basically any form dealing somehow with the principle of containment and/or the articulation of volumetric space through its generative process. I am thinking of the work of Warren MacKenzie but also of Viola Fre/s large figures or Tom Bonhert’s vessels. In my opinion, Viola Fre’s large "sculptures" are as much pots as anything else since they are generated by volume rather than mass. A Rodin bronze is also hollow but the form has been generated by mass. The void inside a Rodin is empty. It is insignificant. On the other hand, the space inside the Viola Frey is pregnant and formally, conceptually relevant because that void articulates the form. It is not empty but on the contrary full, meaningful, significant.

There has recently been a profusion of writings to emphasize the relation of pottery to painting and sculpture, and many ceramists have applied the same position to the making of their work. We have seen Peter Voulkos' plates referred to as "drawings" and Elsa Rad/s pots labeled "still life." These strategies are on the whole legitimate and certainly legitimized by the marketplace, but it is my intention here to establish what constitutes the difference of pottery and to bring some understanding to its nature, not only the nature of the object themselves, but also that of the practice and discipline as a whole.

Recently I came across a lecture given by the French philosopher Michel Foucault in 1967. Foucault was an influential thinker, particularly interested in the relation between power and knowledge. He investigated "otherness," e.g. the mental institution and the prison, and, until his death of AIDS a few years ago, sexuality. This text is titled: "Of Other Spaces" and was published in the Spring 86, vol. 16, no. 1 issue of the review Diacritics.

Foucault’s premise is that the notion of space is central to our time and, I quote, "our life is still governed by a certain number of oppositions that remain inviolable, that our institutions and practices have not yet dared to break down." As examples he lists private space versus public space, leisure space versus work space and, most importantly here, cultural space versus useful space. This last category includes the by now famous debate of art versus craft.

In this category of cultural/useful spaces, he is interested in spaces "that are in relation to all other sites, while they contradict all other sites." These spaces are of two main types. The first he calls "Utopias," which are not real spaces but basically unreal spaces (a category including those objects our culture usually refers to as artworks), and the other he calls "heterotopias" (or other spaces), which are real spaces, places that do exist, where "all the other real sites that are to be found within a culture are simultaneously represented, contested and inverted." These "other spaces" follow five basic principles.

The first principle is that all cultures constitute "other spaces"; they are universal. These other spaces are "privileged, sacred

spaces reserved for specific purposes." They are of two main types: crisis heterotopias like hospitals, boarding schools, or the motel for the honeymoon trip, and deviation heterotopias such as psychiatric hospitals, prisons, or retirement homes for the elderly.

The second principle is that their function is determined by context and changes with time and culture. His example is the cemetery because, although all cultures have places that play the role of cemeteries, this role is different in each culture and also changes as the culture changes.

The third principle is that they juxtapose in a single place several sites that are in themselves incompatible. The theater or cinema is a perfect example: in a real room, a seemingly three-dimensional image is projected on a flat screen and the action might take place in another place, another time, another world. Shopping centers and gardens are also in this category since they bring together objects and species from all over the world, and so are carpets when they are representations of gardens that can be moved in space.

The fourth principle is that they are linked to slices of time either in its accumulation, like museums or libraries, or its transitoriness, like fairgrounds or vacation villages. In our culture, fairgrounds have also become permanent. Disneyland is a good example.

The fifth principle is that they command certain rituals. 'They suppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable." For example, baths or saunas in certain cultures demand a certain ritual in order to gain entrance, cinemas and theaters require tickets and reservations, the prison requires culpability for crime.

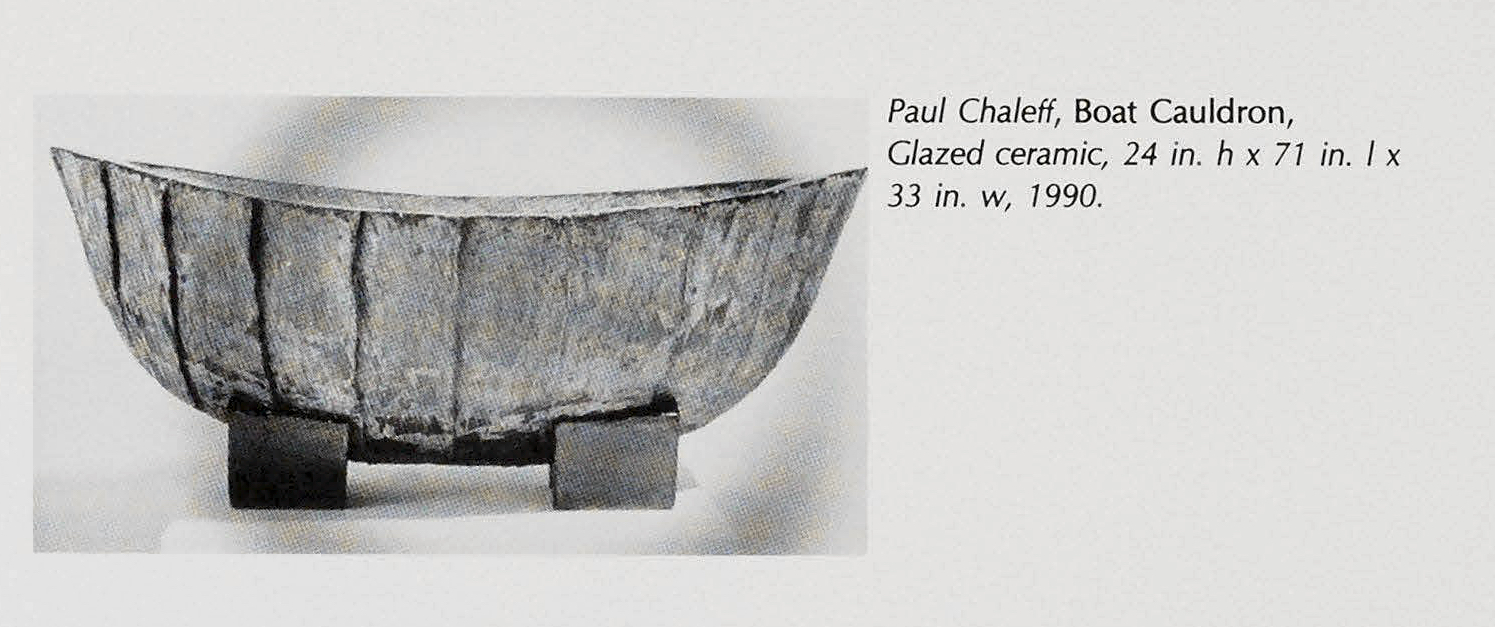

Now the role of these "other spaces" is to create "a space that is other, another real space as perfect, meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled." Mirrors are both Utopias and heterotopias, since they show real spaces in an unreal space, but, according to Foucault, the ship is the heterotopia par excellence, "a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the s e a . . . ."

Well, ships are vessels and so are pots since both are meant to hold and contain, but also move and displace their content. Let's go back to our categories and principles and see how they apply to pottery.

First principle: universality. All cultures make pottery. In the first category, crisis heterotopia, we had the motel room. A ceramic

example could be the toilet bowl. (The bathroom itself is an interesting ceramic space. To use the language of contemporary criticism, it is site specific as well as an installation since all the diverse elements that compose that particular space are distinct, yet in relation with each other.) In the second category, deviation heterotopia, we had retirement homes for the elderly. A ceramic example could be the "vessel." I do not mean this in a derogatory way. I simply see vessels as the domain of the individual, the way prisons or psychiatric hospitals are for those individuals who do not fit with the norm.

Second principle: change with context and culture. Thus, a simple porcelain urinal can become one of modern art’s most famous objects, Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain," or a simple bowl can become a priceless work of art.

Third principle: juxtaposition. Pottery is probably the master of this aspect. In a pot we find in complete symbiosis the exterior with the interior, the three-dimensional form with the two-dimensional surface, the cultural and the practical. Of all art forms, pottery is probably the only one where these seemingly contradictory aspects are so intimately fused (literally). No examples are necessary here.

Fourth principle: relation to time. This also is unique to pottery. The process of pottery is totally dependent on time in a way significantly different from other processes. It is an activity taking place over different times with drastic changes in between.

Each step is transitory and, after firing, these changes become irreversible. The object completed becomes "eternal" in that its nature as ceramics cannot be reversed. Cooking is a somewhat similar process but, contrary to pottery, its results can be, if not reversed, at least totally transformed. Pottery accumulates time and preserves it. For that reason, we know of certain cultures through their pots because they retain their identity through time. Our culture also has transitory pottery, the styrofoam cup.

Fifth principle: accessibility and

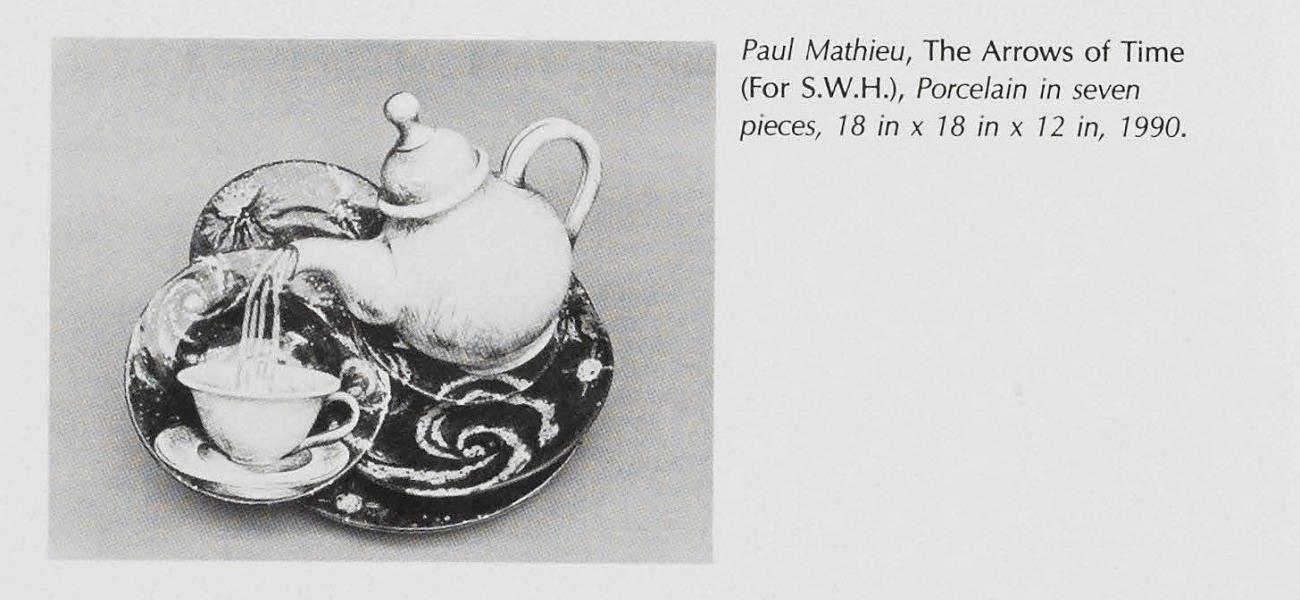

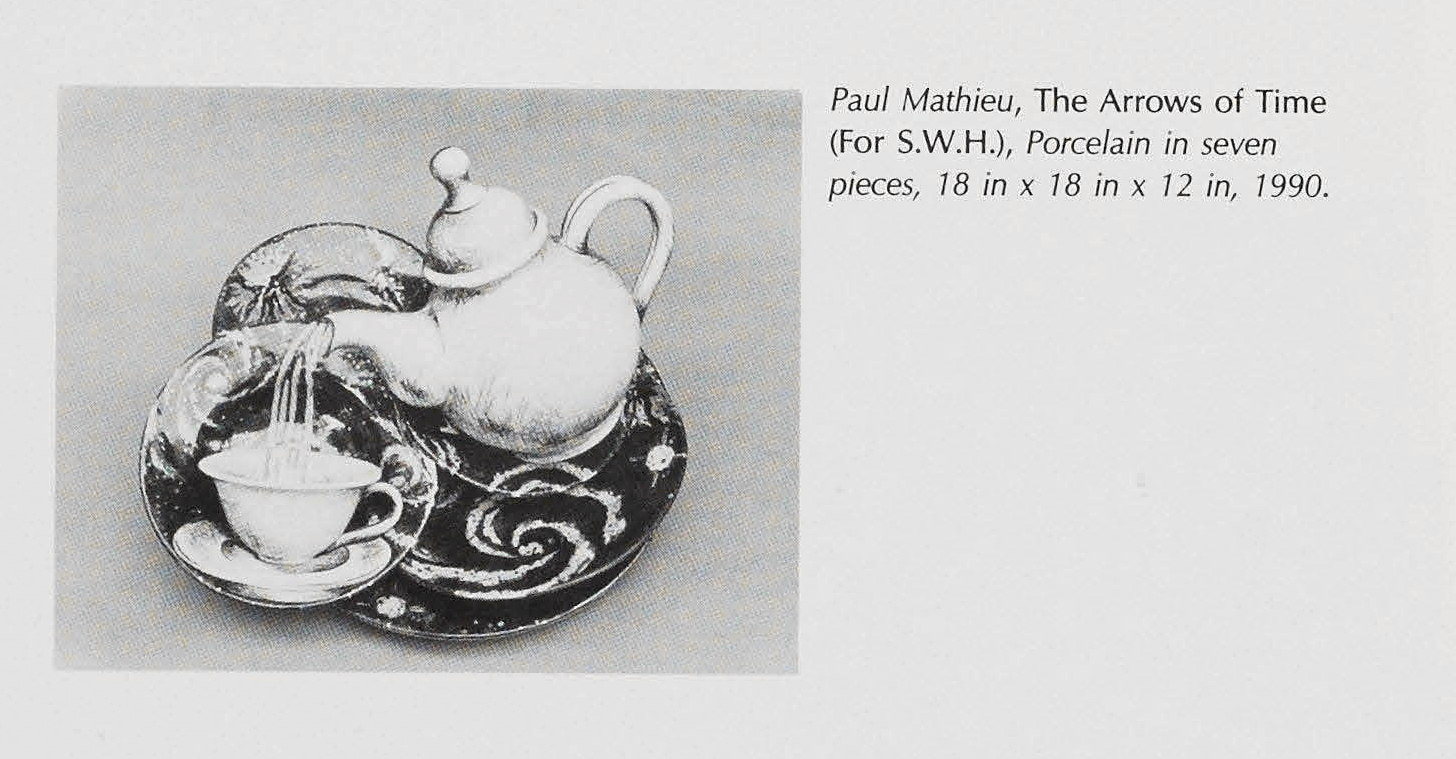

ritual. The relation between pottery and ritual is commonly known, and it is in this quality that pots are "privileged, sacred places reserved for specific purposes," like the morning coffee cup. But Foucault writes that "they suppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them, and makes them penetrable." Obviously with pots we have lids and spouts, but pots are also accessible because their vocabulary of forms, lip, body, foot, handle, etc., refers to the human body.

But at the same time, pots are impenetrable, difficult to understand. Michel Foucault expands on this notion of impenetrability in his book The Order of Things (New York: Pantheon, 1970, p.48) by comparing Utopias and heterotopias: "Utopias afford consolations: although they have no real locality, there is nevertheless a fantastic untroubled region in which they are able to unfold Heterotopias are disturbing, probably because they secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this or that, because they shatter and tangle common names, because they destroy syntax in advance."

'This is why Utopias permit fables and discourses, they run with the very grain of language and are part of the very dimension of fabula; heterotopias . . . dessicate speech, stop words in their tracks, contest the very possibility of language at its source; they dissolve our myths and sterilize the lyricism of our sentences."

I believe this is the reason why pottery finds itself outside discourse and art criticism and why ceramic aspects of Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain" are never considered; they are unmentionable. Of course, it is not the point of Duchamp's work, but it is my point. Why is it so easy to write about art and so difficult to write about pots? Most texts written about ceramics are either technical, historical, or subjectively philosophical. It is difficult to address pots otherwise, they do not make themselves accessible to theory and discourse easily. In our culture, since art is theoretical and discursive, pottery can easily be ignored and rejected or, at least, its meaning misunderstood.

Recently, we have also seen an amazing proliferation of images of pots in contemporary art, especially in painting and sculpture. Numerous examples come to mind-look at any art magazine. More than simple subject matter, these representations of pottery play an extraordinary role. They introduce heterotopias in the realm of Utopias similarly to what happens, in reversal, when a landscape, a figure is represented on a pot. Is the image of a pot on a pot a "homotopia" or a space representing itself?

The reason the art world has such difficulty in dealing with pottery (and other related practices) is not because it is not art. This opposition between art and craft is unnecessary and unproductive. It stems from our habitual practice of oppositions and polarizations (black and white, good and bad, right and wrong, etc.). These oppositions have moral overtones and as such are of no use here. What is important to define is the gray zone where everything merges. In the field of art, pottery is an heterotopia. It occupies a different space, an other space, from the Utopian practices of other art forms.