The Space Between

2006. The war in Iraq was still raging, our children were young, under ten, and our future plans were still unsure. I was an artist-in-residence at the Houston Center for Contemporary Crafts, a few miles away from the stadium where refugees from hurricane Katrina were still being housed. Being Indian and an immigrant weren’t conscious influences, but the political and environmental contours of the day had begun to find an echo in what I was making.

It was during this time that I first saw the photographs of Alejandro Santiago’s work. Sent to me by a beloved artist friend who had seen his 2501 Migrantés exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Oaxaca, they landed on my desk, a contained explosion of expression and raw emotion; the figures powerful beyond words; stripped down, elemental, filled with pain, strength, and mute courage. Those photographs have accompanied me everywhere since, pinned again and again on the walls of the many studios I have occupied, simultaneously shining a light on and reflecting something of my inner self.

Santiago was born in Teococuilco, Mexico, in 1964. He died in 2013, age forty-nine, in Oaxaca. I never met him, but the stories his sculptures tell are no less powerful for not having his living voice. In their unedited immediacy, the figures sound out the drumbeat of the human struggle for survival. From impoverished and unknown artist to worldwide success, Santiago’s own life tracked the classic artist’s dream. As a young student he was attracted to paint and painting people. Human forms remained central to his art throughout his life. He went to school for arts and crafts and began to make a living selling paintings, first in Mexico, then Europe, the United States, and the larger world. Well-travelled and worldly, he lived for a time in Paris, yet his heart remained tethered to the hills of his native Mexico, moored to its arid deserts and its people.

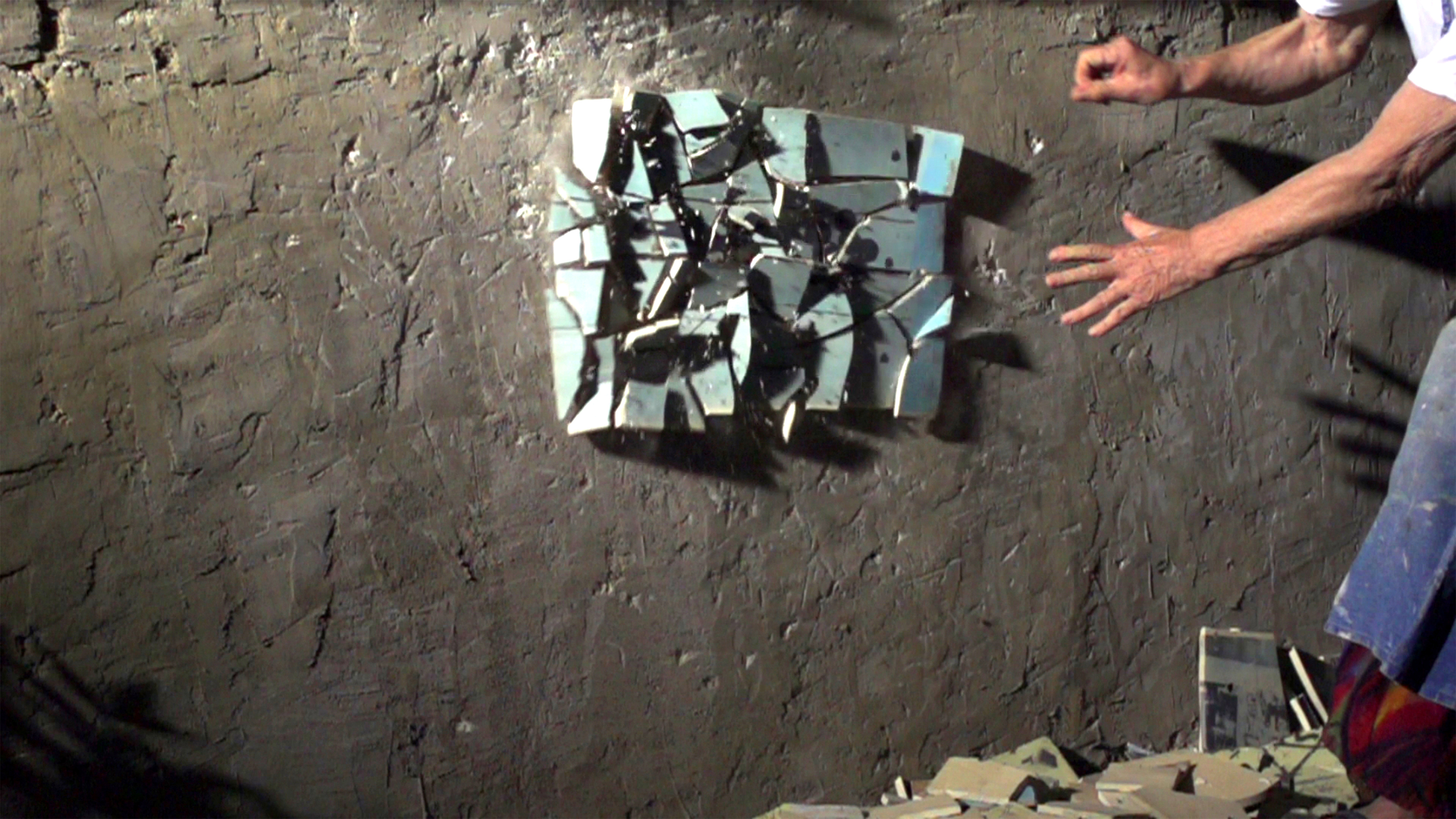

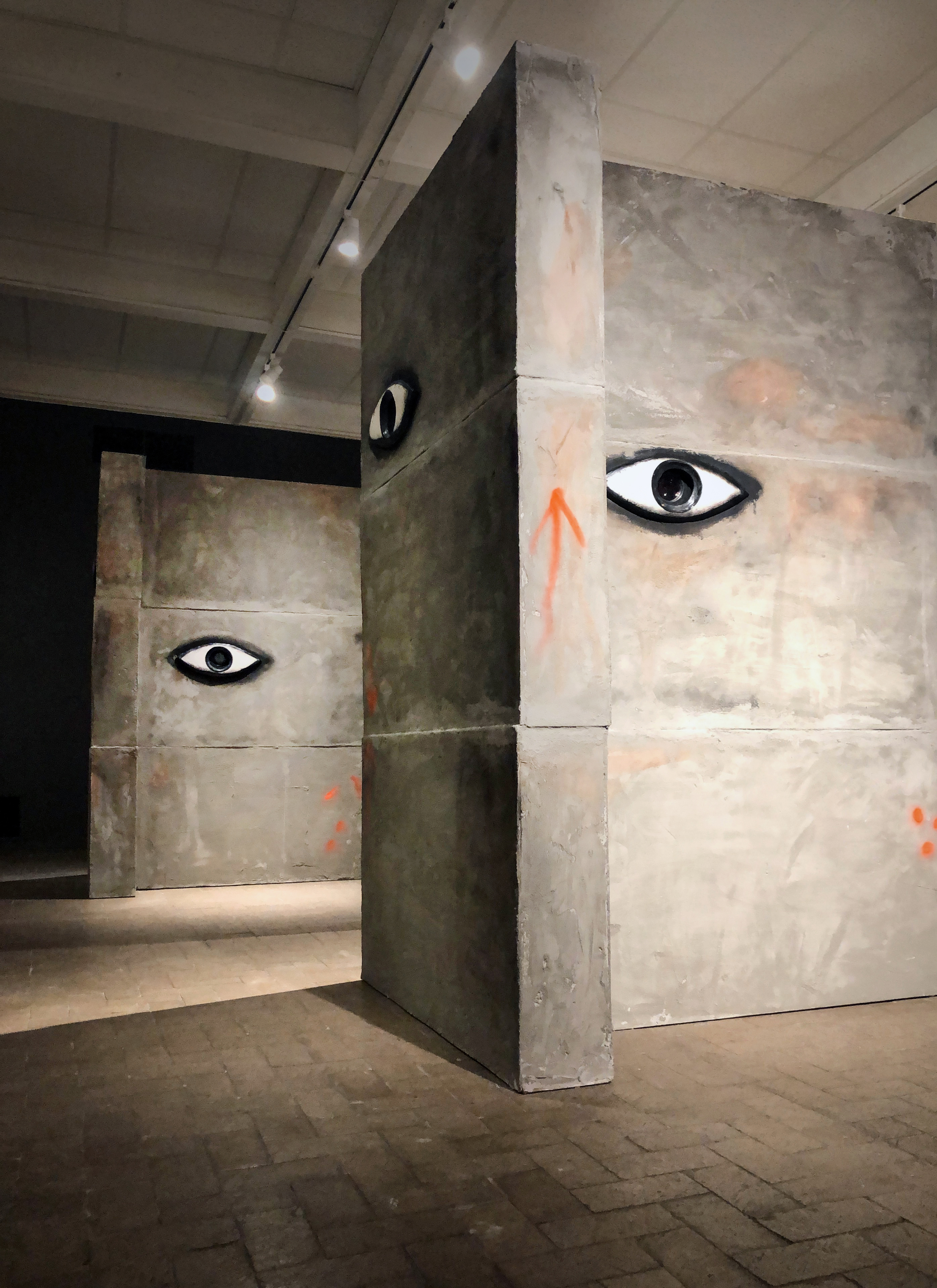

Ten years on, in 2016, at a unique residency in Israel organized by the Binyamini Contemporary Ceramics Center in Tel Aviv and curated by Wendy Gers, ten international and nine local artists worked concurrently over a period of a month. Titled Post Colonialism?, the residency explored and exhibited a body of work investigating the many contentious realities of the fallout of colonialism. It was during this residency that I first saw I Broke Her by Magdalena Hefetz of Jerusalem. Grainy and almost monochromatic, shot in slow motion, the FILM is a cathartic tango of breakage, rupture, and controlled rage. It seared its way into me with the same lightning fusion that quickened my heart when I saw Santiago’s work a decade earlier.

In person, Hefetz, a small woman with a knife-sharp intelligence, projects a cryptic, take-no-prisoners aura. I am a little intimidated, yet drawn, and I welcome the chance to spend a couple of hours with her in her home. After a long day exploring Jerusalem’s Old City and museums, I share a meal with her at a local market. As we walk back towards my car, stepping down through the golden stones of the ancient and troubled city, I catch flashes of her younger self as a potter, artist, rebel, and motorcycle-riding tough woman.

Born in Berlin near the end of the Second World War, Hefetz spent her early childhood at an institution for disabled people who had been rescued from the Nazis. In an autobiographical film that can be seen on the Jerusalem Artist House website, she says that those early years of post-war chaos spent amidst such suffering and overwhelming physical and mental handicaps embedded in her a keen awareness of being different, of being special; fortunate in fact, to have so much when others had so little. The experience marked her life and her art. Like Santiago, regular academics failed to hold her interest and she soon enrolled in the Berlin College of Art. A year later she left Germany to join the Bezalel School for Arts in Israel.

has found herself drawn to shards from her very earliest experiments with raku. Shards speak to her. They are beautiful and potent, carrying history, but also flexible enough for reinterpretation. The action of breaking suits her rebellious nature, her need to provoke thought and reaction through encounter, and it has become an essential part of her creative language. She uses it to interrogate political propaganda by breaking, then subsequently reconstructing and reinterpreting a given narrative. In her film I Broke Her she repeatedly breaks ceramic tiles against the upright and unyielding wall. The tiles are printed with photographs of people interacting with the actual dividing wall – scaling it, painting on it, confounded by it. At the end, as the shards are swept together and buried, they are accompanied by a cryptic comment about leaving work for future archeologists.

I was born in India, a country with a past so dense, so layered and old, that it is practically impossible to wholly describe its psyche. One passes back and forth between the ancient and modern and all the times in between on a daily basis, minute to minute. Growing up like that, amidst the tangled tales of innumerable histories, I have often been consumed by conflicting emotions; on the one hand respecting and admiring the depth and complexity of our heritage, yet at times feeling the need to break through the layered weight of legacy – to let the sun’s light penetrate and heal the buried sores, the wounds we inflict upon each other through ignorance, or worse, indifference. I respond at a visceral level to Hefetz’s actions, the breaking and recreating, bringing into life something new, different, something unencumbered and free.

I live in the US now, in New Mexico, fifty miles north of the border with Mexico. The land here is vast, beautiful, but pitilessly, inhospitably dry. It takes only a short drive out of the shelter of the small cities to comprehend how unnecessary the walls we are determined to build are. The desert is a fearsome enough barrier. Walls carry with them the pain of division and are often merely a dog whistle for an exercise in otherization. As an immigrant myself, I see with an intense clarity the meaning of what Santiago was creating.

The power of art lies in its capacity for alchemy, the ability to reach beyond given circumstances and change perception. In so doing it changes the contours of the space between what is and what could be, and consequently reality. For both Santiago and Hefetz, the power that propels their work transcends technique. Unflinchingly direct about sadness, they reach for hope, speaking to the inner core of our being. Santiago’s figures reach for re-humanization and dignity. Hefetz’s work asks us to recontextualize experience. Implicit at the heart of their work, however, is the idea of freedom. Both speak to the need for it, the joy of it, and seek to change our sensitivities enough to try for it. Santiago passed away too young and we are left wondering what would have come next if he had survived. Perhaps Hefetz’s current work contains clues, if not in form then in thought; cup and jar handles, handles collected from the beaches, given by friends or made by her in her studio, are fashioned into large, globular shapes, creating a form at once dense and light, denoting both agency and community. One supposes that this might have been Santiago’s focus too. To live as a community, to lift each other, to use our strength together. Perhaps by nudging us towards accepting an underlying commonality, we can turn away from differences and toward finding solutions; we could let our young ones actually grow up free from worry and anxiety.

It is a strange time indeed to be writing about reaching beyond and through walls and breaking barriers; now while we are ‘sheltering in place,’ forced to keep a distance, or in some version of an official lock-down the world over. Yet if anything is clear from the global human crisis, it is the awareness of how inextricably linked we are, how porous our divisions are, and how much we need the voices of Santiago and Hefetz.