Set On Fire A Little: An Interview with Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy

Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy is a curator and arts writer with a special interest in craft and ceramics. I turned to her to help answer my questions about contemporary narrative ceramics for this issue. In early 2020, she curated an exhibition of Jennifer Rochlin’s illustrated vessels, "Clay is Just Thick Paint," at Greenwich House Pottery’s Jane Hartsook Gallery. This show catalyzed my attention to narrative strategies in clay and how diverse styles of building and mark-making can fall under this umbrella term while sharing qualities with drawing, illustration, painting, story-telling, sculpture, community building, and, of course, function.

Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy is a curator and arts writer with a special interest in craft and ceramics. I turned to her to help answer my questions about contemporary narrative ceramics for this issue. In early 2020, she curated an exhibition of Jennifer Rochlin’s illustrated vessels, "Clay is Just Thick Paint," at Greenwich House Pottery’s Jane Hartsook Gallery. This show catalyzed my attention to narrative strategies in clay and how diverse styles of building and mark-making can fall under this umbrella term while sharing qualities with drawing, illustration, painting, story-telling, sculpture, community building, and, of course, function.

Angelik generously shared her research and experience, both by email and in a longer Zoom conversation. With my sincere thanks, here is our edited conversation.

Dustin Yager: Over the past few years, as more highly personal, illustrated work has come onto my radar, I struggled to place it into a framework. It didn’t seem like strictly functional pottery, sculpture, or drawing, but it also seemed like a trend in my mind. Of course, it is all of those things, but lately, I’ve come to think of it as belonging to narrative art. How do you understand and locate it, and is it having a moment now? Or do I misinterpret its prevalence?

Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy: Trends are cyclical in the world of ceramics too. Certain approaches to the material come and go, and come and go again, and a narrative approach, especially through the vessel, is evident right now. My mind immediately goes to historical examples for context, from Greek amphoras and Egyptian canopic jars to Qing Dynasty porcelain wares and pottery from Indigenous Mesoamericans that have small drawings on vessels or pots that take the form of a person or a dog, to name a few. It was a way in which people tried to record their stories. You can also see it on walls, like hieroglyphics and murals. But they also did it in this smaller, more transportable way, through pottery.

Narrative content in the form of or on the surface of a vessel is a natural approach to ceramic-making. However, I think it, unfortunately, fell out of favor under the category of the "decorative" when Modernism came about. The surface came second to form. It was an ill assumption that anything decorative was depthless. Much of the artwork in the early American studio ceramic movement is brown or neutral. It’s very earthy; the surface is supposed to complement the form or the material. Funk ceramicists and adjacent artists blew that all up, leading with narrative content, but they mainly worked in sculpture and not as much with pottery forms.

Narrative content in the form of or on the surface of a vessel is a natural approach to ceramic-making. However, I think it, unfortunately, fell out of favor under the category of the "decorative" when Modernism came about. The surface came second to form. It was an ill assumption that anything decorative was depthless. Much of the artwork in the early American studio ceramic movement is brown or neutral. It’s very earthy; the surface is supposed to complement the form or the material. Funk ceramicists and adjacent artists blew that all up, leading with narrative content, but they mainly worked in sculpture and not as much with pottery forms.

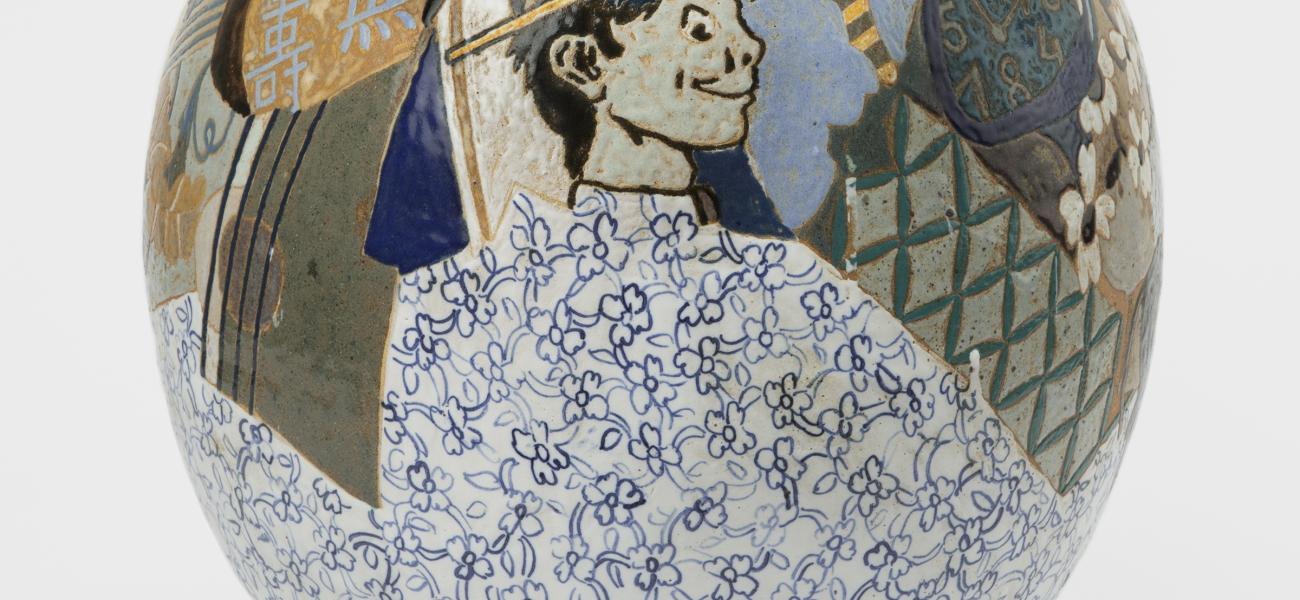

Michael Frimkess (born 1937) and Magdalena Suarez Frimkess (born 1929) come to mind as reviving narrative content on vessels in this period. They were putting all types of little drawings – of things and people – and colors on the surfaces, which says so much about who they are as artists. And that's what's happening nowadays. It's almost autobiographical, the way that artists have been putting narrative content onto their work, especially vessels or pseudo-functional forms, for the past 5 or 6 years, like in the work of Sharif Farrag, Catalina Cheng, and Nicki Green, among so many others.

DY: This work seems fresh and new. However, there are many modern and historical examples of clay artists telling stories and drawing pictures about their daily lives, like Beth Lo and Mark Burns. What makes it feel like such a departure/expansion/update of the field, or maybe just so contemporary?

AVL: Right now, we are in a narrative-driven art world. While aesthetics remain important, being able to back them up with a story is even more of a focus. With the rise of social media, we’ve become an increasingly visual species. We want the visual stimulation, the overload. This, paired with the increased support for artists of color, women, and other underrepresented groups, makes a narrative approach to ceramics ideal. People crave stories. These vessels can almost serve as 3D picture books. We are also past the arbitrary distaste for the decorative, the feminine, humor, and cuteness (among other aesthetic categories), which allows narrative content to flourish in the work of artists like Lindsey Lou Howard, Jennifer Rochlin, Roberto Lugo, Woody De Othello, Emily Yong Beck, Ruby Neri, and so many others.

DY: The Frimkesses were not a big part of my ceramic education, coming from a studio pottery tradition. Can you describe their work a little more?

AVL: Magdalena and Michael are a collaborative, wife-husband team based out of LA. Michael is a master potter, known for the thinness of his vessels and very much about not showing the hand in the pots he made. Magdalena did most of the surface work on the pieces, but Michael did some too. She is more recognized for having an almost "doodle" quality to her work. She's very interested in cartoons, often referencing Mickey and Minnie Mouse, a bunch of other Disney cartoon characters, and Condorito, a Chilean cartoon. Popeye, and what's the name of Popeye's girlfriend?

DY: Right, yeah, the Olive Oyl pots.

AVL: That's right, I know her Spanish name. Magdalena uses all these pop references that people would recognize. In her solo practice, she uses them to make sculptural and tile work in a very expressive style.

Some of these vessels with narrative content seem almost anachronistic because they can be placed at many different times, especially something like Magdalena’s work because some of her work looks Mesoamerican in style. The Frimkesses were ahead of their time.

Some of these vessels with narrative content seem almost anachronistic because they can be placed at many different times, especially something like Magdalena’s work because some of her work looks Mesoamerican in style. The Frimkesses were ahead of their time.

DY: Can you talk a little about the types of messages we see in vessels: small daily happenings, political messages, incredible depictions of identities, and even fictional characters and stories? Do you think the focus or topics of this work have moved over the past 100 years, say, from someone like Viktor Schreckengost to Jennifer Rochlin, for example? Are there periods when politics or identity have been a focus or forbidden, or daily stories are hidden or celebrated? What is the particular confluence of factors that are contributing to this rise at this time?

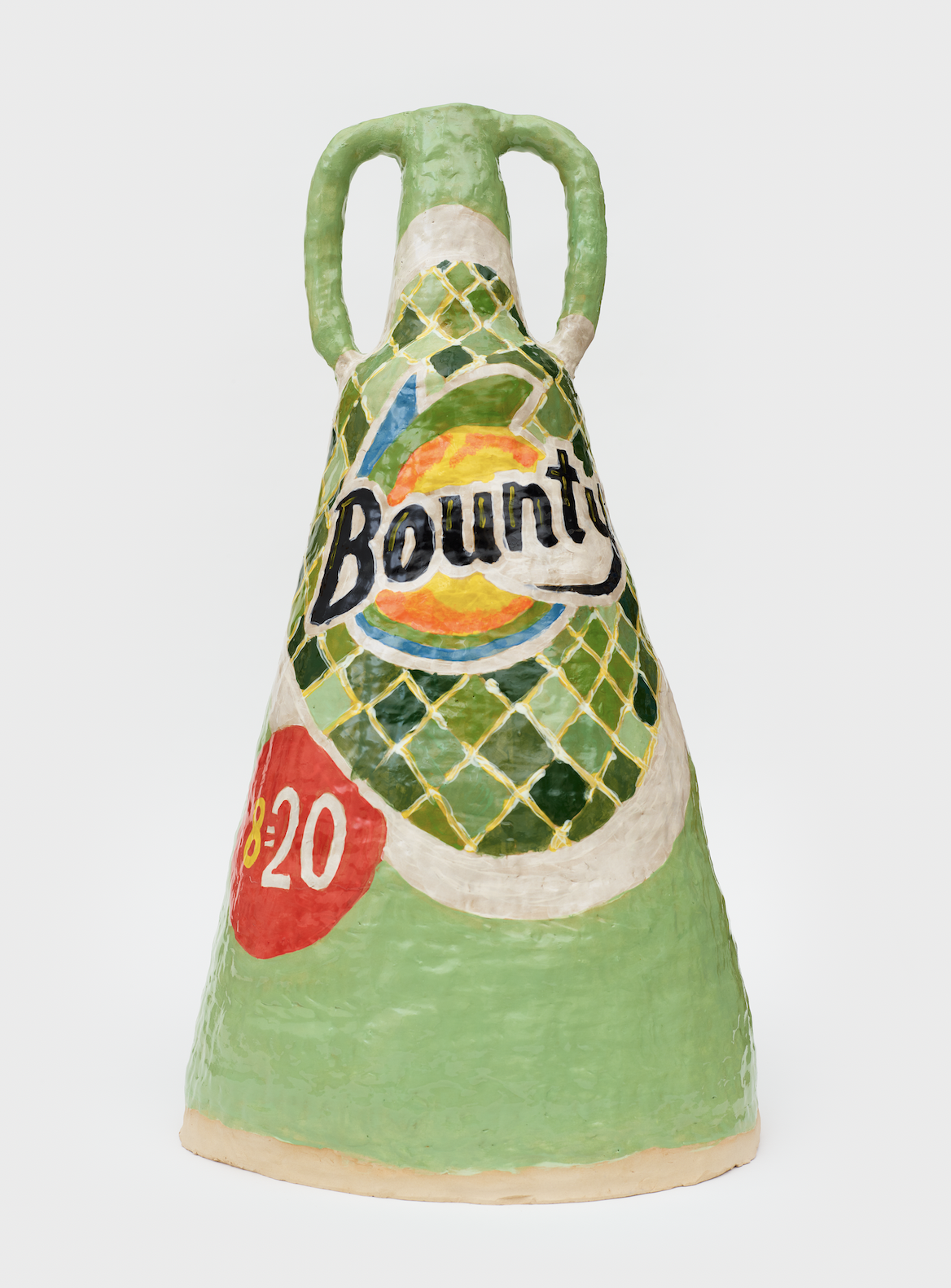

AVL: The personal is political. While many of the artists we have mentioned have a diary-like approach to their work, ultimately, it is inherently political because they set up a dialogue with a long list of issues, including racism, misogynism, homophobia, and consumerism. A great historical example is the work of enslaved potter David Drake, who began inscribing dates, signing his name, and writing poetry on his functional jars, which was a radical act.

Identity-based work is a significant focus in art, especially after the cascading effects of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests.

And because of social media, we are more comfortable sharing with others and are almost trained to do so. The thoughts we might include in a post can be downloaded onto the clay instead.

Funk and Funk-adjacent art, especially its continuation in the contemporary realm, has been a research topic of mine for almost six years. Artists tend to lean heavily on narrative and humorous content when things are especially tense politically and socially. Funk was at its peak when the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement were happening, and the revival of this approach came with the Trump presidency and the blatant onslaught of oppression and bigotry in the US. I have translated this research into the exhibition Funk You Too! Humor and Irreverence in Ceramic Sculpture, opening March 18 at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York, and its accompanying catalog.

A lot of contemporary work has serious, dark connotations to it. But the first impression is one of joy or fun. It is happy but sad at the same time. A level of subversion and humor is coming through in this kind of work related to the political situation in the US. Subversion is so popular because instead of getting defensive when you encounter work that is heavy, you get a moment to process the information.

The personal stories in these artworks often coexist with pop culture references too. There is a layering that reflects the artists’ identity, their experience in the US, and their pursuit of belonging. This country is a contentious place when it comes to existing, especially if you are "othered" in any way.

DY: I was listening to an episode of your podcast, Clay in Color, that you host with Alex Anderson, and Sharif Farrag says his work "calls out to the fam" and calls out to the people who are willing, able, and interested in spending a little bit more time with that work. And maybe who recognize the stories and the signifiers that are being put on public display. And that often comes from marginalized people, first and foremost.

AVL: There is a myth that art has to be universal, but it is not. A story might speak to some people, and it might not to others. And that's totally fine. What is universal about art is that you can access it in different ways. Stories resonate better with those who can empathize, but not everybody has to relate as long as they respect the artist's perspective.

DY: Another issue that came up in some of your podcast interviews is about trust and authenticity. There are some artists –I’m thinking of Emily Yong Beck – who think a lot of art history borders on propaganda. And the only way that we can have any kind of truth or authenticity is for the artist to tell their unique individual story today. And that's the one point in the world that they know to be reliable.

AVL: We're at a point where there is not one history but a million histories to be shared, dissected, and critiqued. We desire to hear those stories that have been underrepresented and ignored for decades and decades, if not centuries. In the field of studio ceramics, there was a time in which, basically, it was all white dudes, with maybe some white women and some Japanese folks in the mix, that were getting the attention. And now, there's an effort to rectify that, and we thrive on celebrating different perspectives.

DY: If I can pull on another thread of this confluence right now, it’s maximalism. The hyper-colors, the overlapping patterns, images, text, and texture. The narrative artists we’ve been talking about really load their surfaces!

AVL: Maximalism is super in right now. Or I don't know if the algorithm knows my interest in maximalism too well. Maximalism reflects the world that we live in, in which we have these tiny machines in our hands bombarding us with so much content. Maximalist surfaces are a mirror image of that.

As you said, the maximalism of these ceramics involves an abundance of surface treatments, colors, and elements. Still, there's also a dystopic feeling to a lot of it. There's this sort of melted quality to it. It looks like maybe it’s been set on fire a little. There's optimism and a feeling that we're headed toward a dark place. Those coexist for sure.

DY: I am curious about some specific themes (or memes) and pictures that I see popping up in the work of multiple narrative artists. Frogs are having a moment right now, for example. And foods, depicted in that melted dystopian way, or branded products. What is it about these cute and everyday items that are attracting a cohort of artists as sort of shared symbols?

AVL: I’m not sure why these specific animals versus others, probably because of familiarity and accessibility. Some things have a symbolic significance, and some don’t, but there is something compelling about doing whatever you want in your art. But talking about frogs, I think of David Gilhooly, of course. Funk artists didn't originally intend to make political work. They got more pointed over time. But those original sculptures were political because they went against the expectations of what ceramics should be at the time. And against the expectations of art in general. Why a frog? Because, why not?

DY: It’s kind of like the impulse was the same then and now: "because I can," but it's just pushing against a little bit different structure.

AVL: Everyone's reacting to something – we don't live in vacuums. There are so many things happening that we are tuned into, even just instinctively. And it all comes through consciously and subconsciously in the work artists make. Some work is really intellectual, and some work is looser. There is a context for everything.

DY: It seems like there is also a role for technology in this discussion. Kilns are much more accessible, for one, as are material suppliers in general. Social media makes it easier to share stories, which inspires others to iterate in their own clay practice. I’ve even thought of some of this work as the vitrified version of a TikTok video: seemingly quick and daily, quippy, and highly personal, but also involving a specialized skill and a particular point of view. I think it is sometimes dismissed by more traditional potters, but it holds many of the same qualities of personality, originality, and functionality that we hold as virtues. Does this relate to our particular digital lifestyle, with or without a pandemic twist?

AVL: Social media is one-hundred percent a factor in the rise of this kind of work. And many of the artists approaching ceramics this way are very active on social media platforms. As much as people love to hate them, social media platforms (Instagram and Tik Tok, especially) are some

of the biggest forums for artistic discourse and networking. The artworks we have been discussing look good in person and digitally. They have it in their DNA to thrive on these kinds of platforms.

DY: As we share names of artists who fit under this banner, we included artists who make pots and sculptures, and artists who use a vessel form as a canvas, and artists who make functional pottery. How do you interpret the use of the vessel (abstract or functional) for a narrative rather than a sculpture, drawing, or some other form or medium? What does the pot lend that other forms do not?

DY: As we share names of artists who fit under this banner, we included artists who make pots and sculptures, and artists who use a vessel form as a canvas, and artists who make functional pottery. How do you interpret the use of the vessel (abstract or functional) for a narrative rather than a sculpture, drawing, or some other form or medium? What does the pot lend that other forms do not?

AVL: For many, the obvious answer would be functionality. But as we know, that is not the intention of most of the artists we have been discussing. The field of ceramics is incredibly referential, and the vessel is the most iconic clay form. It is a canvas by another name, and many bored with or trying to push beyond the linearity and flatness of painting on canvas have turned to the vessel instead. The vessel presents a different way of sharing a story because you have to contend with the curves and angles. You can play with two- and three-dimensional aspects, as well as inside and outside. A vessel can be a microcosm of infinite narratives.

The choice of the vessel is also one of familiarity. We have all engaged with a vessel at some point in our lives. It is a form that has ensured the survival of humanity by storing water and food. It also holds a lot of symbolism as something that can metaphorically hold something, and it is a proxy for the body.

Most artists make a conscious choice about whether they want their vessels to be functional or not. Some people have dedicated functional pottery practices; for others, the vessel is only a vehicle for storytelling. Another cool thing is that, more and more, we are seeing the definition of a vessel being stretched. For example, Ruby Neri builds a huge vessel but in the form of a woman and, through that, completely subverts the expectations of a vessel.

DY: For me, I think that making it a vessel makes it domestic; it makes it approachable on a table level. The only thing domestic about it is that it's a vessel, and the meaning, the concept, is what I’m more interested in, but I like to put it in a household context.

AVL: We all likely have a vase in our house for when we get flowers or other vessels around the house that we are constantly using. But many artists employing the vessel are looking to push the traditional definition as far as it can go to cut out domestic or functional connotations, but not so far that it is not recognizable as a vessel.

DY: A parallel trend that was in my mind, thinking about how to put this issue together, was lumpy work and work that so distinctly shows the hand and the de-skilling process. Ultimately, I decided, that is something a little bit separate, but I wonder if that is also an analogy for narrative, or to be able to place the maker into that piece in a more abstract way, just by showing that a person was here.

AVL: It’s fascinating to see the forms that can come from deciding not to be so perfect. It's an opposition to classic pottery ideals, whether there is a focus on the thinness of the walls, the pot's not rocking, or its being centered. Lumpy forms are a rebellion against that. Many of the artists who are working in this way aren't trained as potters. So that's partly the reason—that's not their training, and they don't care to make a perfect pot. But even those artists with the training know that imperfection adds interest and helps tell a personal story. A lumpy form can add to the symbolic unevenness or shakiness of whatever narrative content is put onto the piece. It is also more challenging to be able to tell a story in a form that’s not smooth.

Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy

Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy is a writer and curator of contemporary art and craft. She has curated and juried exhibitions across the United States, including at the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento; Guerrero Gallery, Los Angeles; Mindy Solomon Gallery, Miami; the Center for Craft, Asheville, NC; Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ; and the Museum of Arts and Design, New York, among others. Vizcarrondo-Laboy has written for multiple exhibition catalogues and publications. She is the creator and co-host of the Clay in Color podcast.

Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy is a writer and curator of contemporary art and craft. She has curated and juried exhibitions across the United States, including at the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento; Guerrero Gallery, Los Angeles; Mindy Solomon Gallery, Miami; the Center for Craft, Asheville, NC; Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ; and the Museum of Arts and Design, New York, among others. Vizcarrondo-Laboy has written for multiple exhibition catalogues and publications. She is the creator and co-host of the Clay in Color podcast.