The Secret Life of Pots

For the past twenty years I have sold work at a large arts festival near my home. In four days a quarter of a million people attend this event, several thousand of whom file past my booth, a few hundred of whom stop, and a small percentage of those who look at my pots ever move to within arm's length of them. Picking up one or more of the pots may occur to some who pause and look, but the ones who examine my work closely are a tiny minority of all who pass by. When I consider the huge number of people in the town who don't even attend the festival, the small constellation comprising my clientele seems especially remarkable.

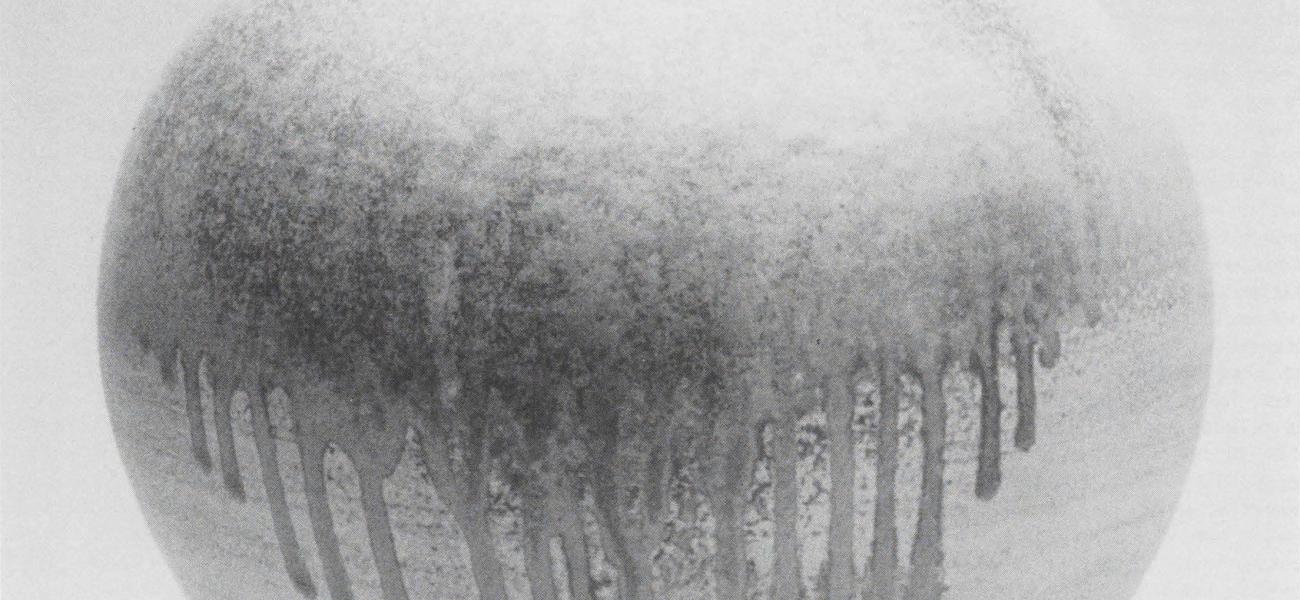

One of the main reasons I continue to do the festival is that I enjoy watching someone focus on one or more pieces, becoming acquainted with them, turning them around, examining colors and textures, often completely oblivious to me or the nearby hubbub. In the visually competitive scene of the festival, my anagama- fired pots glow rather than shine. They don't leap out at passers-by.

I have seen people move toward pots as if they held a forked stick in their hands, divining something without a name, like a person witching water. I like to keep out of the way when I see that happening, letting whatever passes between them take its course. That contact, that magnetic sparking is, after all, what I work for in large part, and I honor its power. Good pots pass through many hands, and watching these first exercises of preference is a quiet treat for me. These wordless, primary encounters are at the core of our attraction to favorite pots; by comparison, written criticism is so much underwater yodeling.

I often wonder what leads people to pots, and hope no one ever hands me a definitive list of reasons why. Ifs enough to acknowledge and exercise this aesthetic appetite-one of the truly harmless pursuits available to humans-without justifying it rationally.

If you've ever built a stone wall or watched someone else do it, you know how it is to look at a space, then house the space while seeking a stone to correspond to it. That’s how it is with some pots we come to love-we approach them with readiness, as if we contain within us a space the pot fills. If we are fortunate enough not to have read anything about the piece or its maker beforehand, our approach is the purest possible. (In the absence of criticism it is impossible to appreciate anything for the wrong reason.).

Ifs encouraging to see and meet people who make the time for aesthetic decision-making—one of life's few pleasurable dilemmas. Among those for whom I wrap up pots, some few are remarkably uncurious about how and why this thing they have space for in their lives has come to be. They assume, I suppose, that the side of the pot they can't see is really there and intact; they simply point and say, "I'll take that one." Others leave my booth with a pot or several, after grilling me about woodfiring. Occasionally, I feel that I've just passed a tough oral exam about the kiln and firing process What I bring with me to the festival, along with my work, shelves, chairs, and cooler, is the invisible information about why this work is the way it is. I have often sought to draw this kind of background from students when I've occasionally assigned them an essay entitled 'The Secret Life of Pots" at the end of the semester.

The secret life of pots may go back so far that our sense of geologic time and our imaginations must be compatible for us to appreciate each clay object's origins. Such origins are factual; our appreciation, however, may stem from "felt knowledge"-information that reverberates in our being rather than simply accumulating in memory. Felt knowledge is associative, enabling us to see elements of one thing in another; to make sensory connections the way a woman once touched a textured zone on a pot I'd made, saying, "It feels the way I imagine Mr. Nixon's cheeks to be." Imagination rooted in fact enables a potter to reflect that in thirty good working years, a decent thrower can convert a house-sized piece of a mountain into cups enough for everyone in a small city, and in the process build or pay for a place to live and work.

Thinking about pots and their secret lives began for me when I read an interview with Ray Bradbury years ago in Playboy. Bradbury had the notion that pots might contain the sounds of the places where they were made, since the fingers of the potter could function as a crude stylus, imprinting vessels with sound waves that would remain forever trapped in the fired work. With the right technology, we might play back those crude Roman jokes hidden in otherwise mute pots, perhaps liberate the song of a nineteenth century wood thrush from a Bennington jug, release a thunderclap hidden in an Anasazi cup, hear the biwa thrumming in Rosanjin's plate.

The secret life of pots can be informative on a more mundane level, too. I know of a salt-glazed crock made in a nearby town about a hundred years ago. It is stamped with a "5" above a large blue flower painted in cobalt slip. On the rim are scratched the numbers "17 1/4." Measuring the crock, I find it to be only thirteen inches high and to hold only four gallons. That missing four-and-a-half inches due to fired shrinkage would have contained the extra gallon the crock was thrown to hold. A century later, those numbers show me one potter's exasperation with the high shrinkage rate of his clay. In the days before standardized units of measure, crocks stamped with numbers were commonly used in stores which sold products from bulk, and presumably a potter could be held accountable for short changing customers. The simple translation of 17 1/4 then, is that in order to produce a true five gallon crock the potter would have to throw one with more than a six gallon capacity to compensate for shrinkage-as depressing today as it must have been then.

Pots may retain for us poignant and evocative qualities. Years ago, I visited Arie Meaders, the widow of Cheever Meaders, Appalachian folk potter, in Cleveland, Georgia. In the old shop I bought a face jug made by her son, Lanier. I remember walking back to her house on a path through a pine grove. She wouldn't live much longer, as it turned out, and she sat on the porch, holding the jug. I said I thought it was a good idea for a potter to walk a little distance, as we had just done, from the shop to home, if just to track the clay from one's shoes. She turned the jug to face me, and handed it over, saying,

"After about this many years, it gets kind of boresome." When I look up at Lanier's jug in my studio, "boresome" is what it seems to be saying. This evocative aspect of pots can degenerate into fetishism or simply amplify our appreciation, depending on who's making the call. The extent of a developing connoisseurship for early American stoneware is enough to jostle a potter's perspective pretty severely. Recently, especially since the stock market fizzle in the fall of 1987, prices for exceptional pieces have risen to around $50,000. In pre-inflation terms, the secret life of these pots reveals they were made by potters who received a penny a gallon for their throwing, with finished work selling for an average of three to five cents per gallon. Potters were expected to throw 100 gallons of ware per day. Clay cost about $5 per ton, wood $2.50 per cord. One pottery, in West Troy, New York, employing two potters each at $25 per month, turned out $500 worth of stoneware from 10 tons of clay and 25 cords of wood in I860.1 The astonishing value currently placed on work made in such shops, mostly by anonymous craftsmen, is bewildering, to say the least. Even in rough comparative terms, what potter could ever imagine a pot he had made, and perhaps his wife had decorated, ever selling for a price equal to the annual salary of a wealthy businessman?

Regardless of the worth or value we confer on ceramic objects, they seem ripe for appreciation, and the roots for that enjoyment are ancient. Perhaps there are no new ways to appreciate pots; maybe we just keep relocating within ourselves fresh old connections, trusting the same nonverbal guidance systems that have led all humans to what they connect with and come to love. Every pot has its secret life, at the convergence of fact and imagination, discovery and memory.

I can't think of the secret life of pots without recalling a story that was told me late one night in a Vermont farmhouse by a potter I met only once. I think of the group of tea bowls that figure in the story, and the role they played in the teaching and learning that went on over them that day they were unloaded from the kiln. I'll call him Richard.

He had worked in a Japanese pottery for over a year and had learned a great deal about the facts of a potter's daily life. One thing he had to endure was his teacher's habit of describing Richard's work in only positive terms. "Much goodness in handle, Richard," the old man would say. "Much goodness in brush stroke."

In his heart, Richard was a confrontationalist, and in the course of that year the parts of his pots the old man never mentioned began to worry Richard. Things his mentor didn't say began to accumulate in Richard's mind-clinkers of anxiety. He longed to confront this sly sage . . . "Well, what about this spout?" "What do you think about this lid?" And why was the old man so focused on details? How come he never acted as though he saw the whole pot? And were the parts without "goodness" weak, wretched, simply not worth mentioning, or about as good as those that were pointed out?

At the conclusion of his stay, Richard made a series of tea bowls. Determined to learn his teacher's honest opinion about his pieces,

Richard let him have his say, "Much goodness in tea bowl, Richard . . . much goodness in rim."

"Look, what about the feet?" Richard asked, maybe a little abruptly. The old man had already turned over all the dozens of tea bowls; had carefully handled each one.

"Goodness in foot, Richard," he said, looking directly at the foot of one tea bowl, "as y e t . . . undiscovered by me." V I take heart in that goodness awaiting discovery. Pots we've yet to encounter contain it for us, even as I write; even as you read.