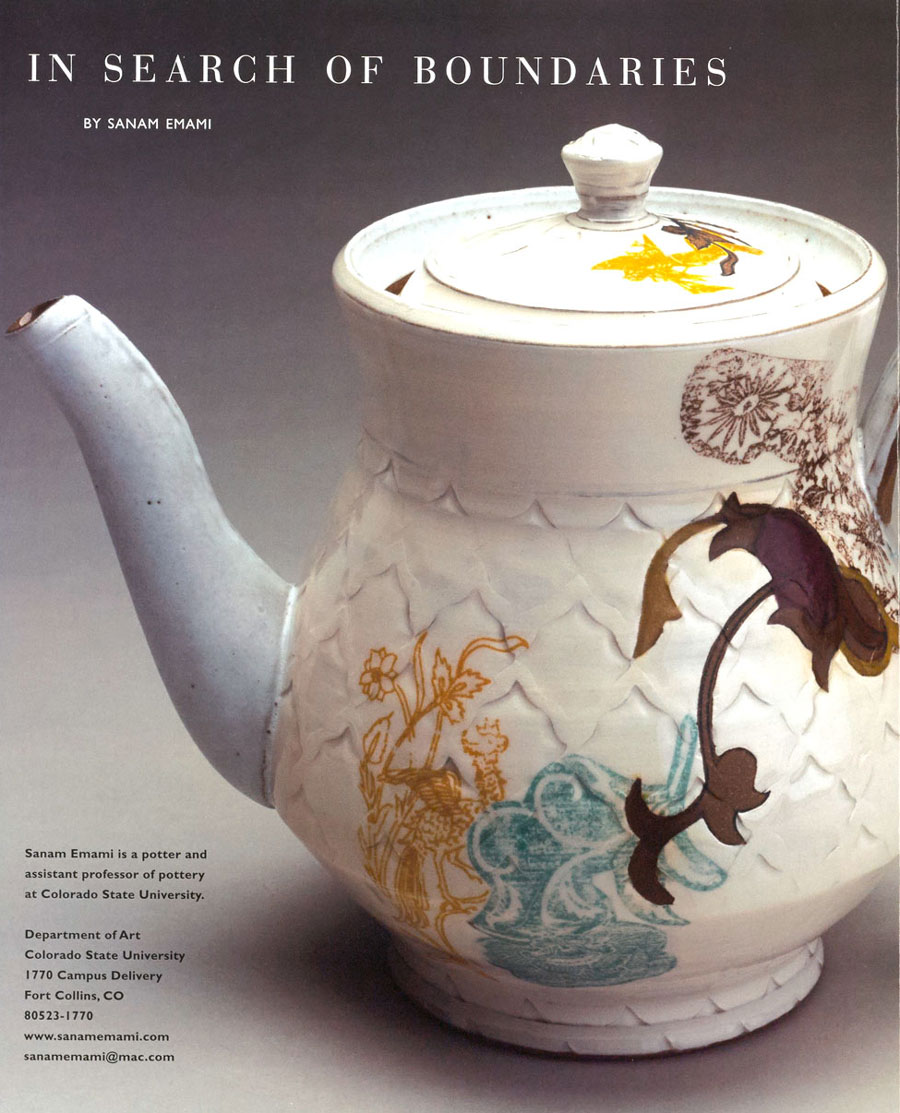

In Search of Boundaries

So what is the place of boundaries for an artist, a potter, a writer or poet, in this age of digital information and multidisciplinary approaches? In an era of dissolving disciplines and skill-based practices and of merging genres, how do we understand or use boundaries?

When I was twenty-four and had been out of university for three years, I made a decision to be a potter. In many ways, this was completely counter to all I had done up to that point. I had chosen history as my major, mostly because of the few required courses. I had taken classes in philosophy, religion, and sociology and had earned enough credits to make up my own curriculum and focus my history studies on women and the Middle East. My views about art and clay at that time were also cross-disciplinary. I had studied ceramics, drawing, and printmaking, but I had stopped short of getting a BFA because I felt that the major had too many requirements. I wanted the freedom and flexibility to choose my area of study and felt that the existing structure of the art major was too restrictive, with too many boundaries. The ceramic works I made in undergraduate school were mixed media sculpture and installation.

For three years after finishing my undergraduate studies, I lived and worked in San Francisco. I floated between jobs and identities, just as I had floated between departments in college. I worked an office job to pay the bills, but I also volunteered in a women's free clinic, interned at a gallery with a focus on installation art, and began to work in a clay studio.

Everything from my past experiences and choices would seem to have led me to a field spanning many genres or disciplines. Instead, I chose to be a utilitarian potter. I was idealistic and imagined, as many young students do, that pots were an accessible and democratic art form. This I still believe. I also chose to believe that the pot had parameters I could readily understand, and this, I thought, made the concept of being a potter something simple. There were always challenges, but I assumed they were technical ones that I could overcome. I had felt overwhelmed by the unlimited choices I was considering; I wanted to focus on something finite and tangible.

As soon as I seriously engaged in making and thinking about pots, the simplicity quickly faded and countless possibilities began to take shape in my mind. Defining the pot became more and more elusive and nuanced. Lucie Rie said that to the untrained eye, all bowls or pots look the same, but to the trained eye the possibilities are endless. A boundary that is fixed and permanent can impede creative thought or action, but some boundaries are elastic and malleable. The concept of the pot is this kind of boundary: a set of qualities that differentiate one kind of object from an other. When that became clear, the decision to make pots provided me an entry point into a creative practice.

I originally thought I would develop this idea of restraint further in this article, by examining how the parameters of function, utility, tools, and materials have allowed me the freedom and flexibility to imagine a sustained inquiry into the making of pots. I had planned to write about how the concept of a boundary is helpful to me. I do not see the focus of pottery-making as inhibiting my creative impulses. Instead, the limitations of one material, of utility and function, set up a series of questions that I explore daily in my studio work and with my students. These are flexible boundaries, not fixed or static. They set into motion a series of focused questions that can be reconfigured, reorganized, and turned inside out.

As I wrote I began to consider another point of view. I realized that although my life is consumed with pottery, perhaps I am not a potter. "Making pots" describes only part of what keeps me continually engaged with the pot. In a sense the physical pot could be defined as only one kind of boundary. The pots I look at and discuss with students and peers, the pots of our shared historical past, and the pots in my imagination, the ones I want to make in the future, create a vast physical, theoretical, and hypothetical world- a world of ideas, concepts, and questions that I imagine will sustain me for years to come. My interest lies in thinking about the pot, looking at the pot, and talking about the pot. I realize now that being a maker is not all-encompassing. What pottery represents and has the potential to represent are as important to me as the act of making.

Somehow, I've come full circle. The pot was meant to give me focus and allow me to delve deeper within the boundaries of utility and specific intent. That focus has opened up a world of possibility.