A Plea for Sanity

On November 13, 2025, I sat down, remotely, with Richard Notkin for an extended conversation about his life in clay and the principles that have fueled his practice.

Notkin, who has spent nearly sixty years making work that confronts war, challenges the failures of human leadership, and probes humanity’s fragile relationship with the environment, speaks with the clarity of someone who has never separated his artistry from his ethics. With characteristic frankness, he traces the events that shaped his worldview – from Cold War tensions, to the Vietnam era, to today’s global instability. What follows is a masterclass about art as conscience and craftsmanship as conviction. This interview captures an artist looking backward, forward, and unflinchingly at the present.

Editorial note: Portions of this conversation have been refined for clarity and readability.

Richard Notkin

I've been working in clay since 1968 and dove into it quite seriously in 1969 when I changed my major to the Ceramics Department as an undergraduate student at the Kansas City Art Institute. I’ve been an artist working primarily in clay for almost six decades.

I love the material – the many different clays. I love the many processes, the plethora of techniques. I am still a student. I'm still learning. There is no end to the possibilities.

I developed ways to adapt clay’s many capabilities to become an excellent vehicle to express my concerns about our planet, our nation, the human condition, and human civilization.

I am currently living and have lived for almost twelve years on the Key Peninsula in the southern Puget Sound, about an hour and a half from Seattle, in a very rural area. But I'm about to move back to Helena, Montana. I guess Montana never quite left my heart. I lived there for twenty years prior to living here. I’m now seventy-seven years old, and the transition will be a severely daunting task, given that Phoebe and I are moving not only a home but two very full studios again.

Randi O’Brien (ROB)

Are you returning to Helena because of the Archie Bray, or is it the larger community that’s drawing you back?

Notkin

I think the Bray was the initial magnet that attracted me to Montana, and Helena in particular. I was a resident artist at the Archie Bray Foundation in 1981 and never stopped having a relationship with that incredible place. I moved back in 1994 and lived there until 2014. I was deeply involved on the Bray board for a long time, but now it's mostly the incredible arts community in Montana that is drawing me back – so many wonderful friends and people I've worked with over the years. And it's just a deeply connected arts community. It's not like the big bright lights of New York or Hollywood with the lure of fame and fortune or anything like that, but it's a place with a mostly altruistic group of creative people, many of whom are making meaningful and compelling art for all the right reasons. I have encountered similar communities of artists all across our nation, all over the world.

ROB

Speaking of "making art for all the right reasons," we’re having this conversation because you received the inaugural Virginia A. Groot Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award. At this point in your career, what does this recognition mean to you? And do you feel a particular responsibility that comes with it?

Notkin

Well, I'm just incredibly grateful to the Groot Foundation for the recognition that this award brings to my art. It's just a phenomenal recognition. Prior to receiving this award – which I was not even aware existed – I contacted them because I have this vision of a project I intend to create for the rest of my life. It is an ongoing installation which basically continues all the themes I've imbued in my work, the political and social commentary, the anti-war, anti-nuclear weaponry, and growing themes of climate change. Because it's a non-commercial gallery venue approach, I needed to find support for its ongoing creation.

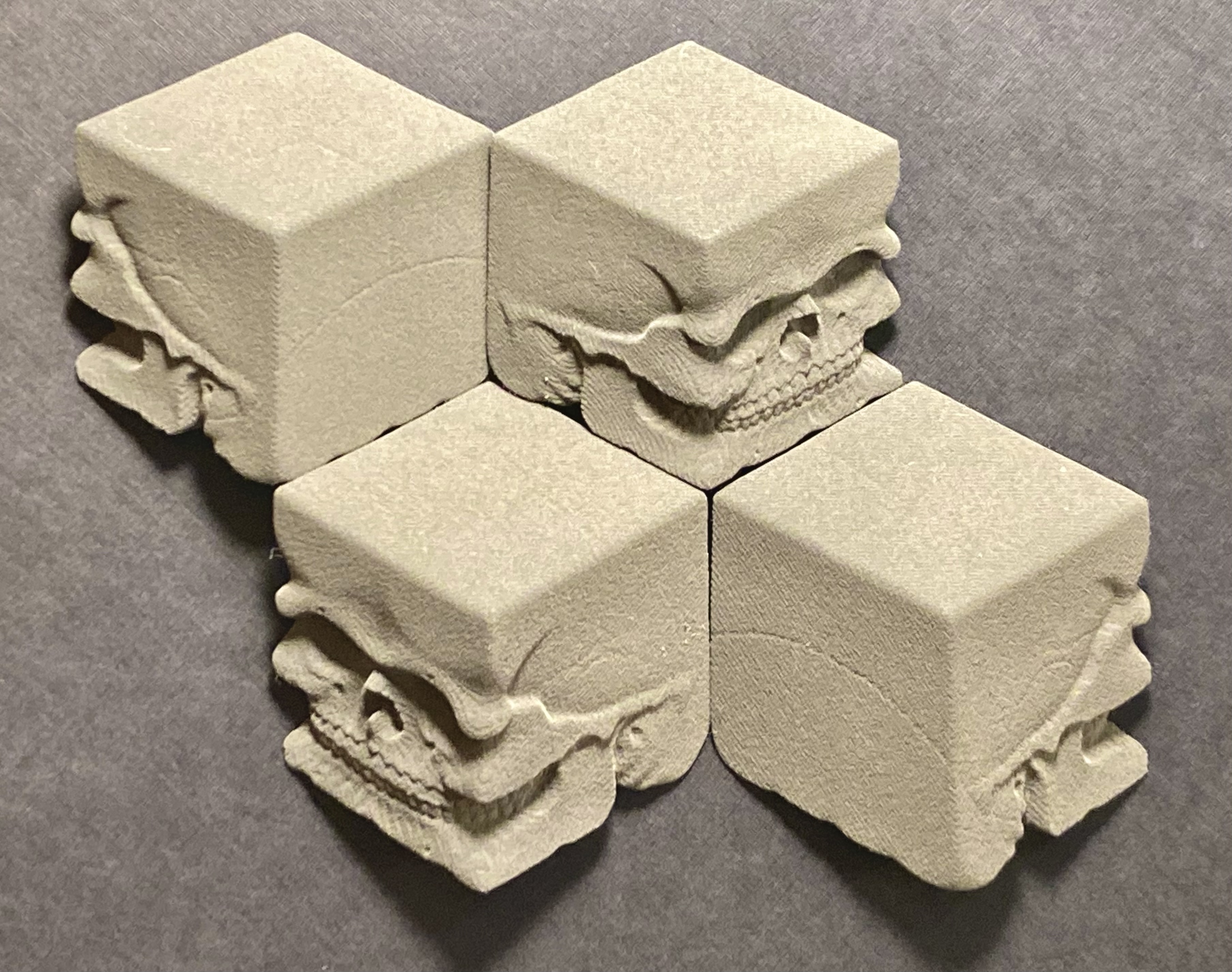

My wife, Phoebe Toland, who's a painter, and I rely on Social Security, Medicare, and our savings, which we hope will carry us through our later years. But as we get older, the reality of having no steady income sets in, and I realized I needed to reach out for support again in the form of fellowships or grants, something I hadn’t done in a while. And so, when I got a call from the foundation telling me that I had received this phenomenal recognition – the inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award – I was shocked, elated, grateful. It's quite an honor. It will enable me to now get this piece off to a quicker start. I actually began conceiving it a few years ago while working at several digital Fab Labs, creating 3D printed prototype models that are being used to produce molds for ceramic castings.

The award’s recognition certainly is most encouraging. It seems to indicate that my art has achieved my main intention – to have a profound impact on its viewers. The award also has the potential to expand the audience, the number of people who will see my work. Ultimately, I'm more interested in that than anything. It's not about my career. It's really about the message that I'm putting out there to be seen, deciphered, and absorbed. What's the point of putting messages in your work if nobody sees them?

ROB

That makes absolute sense. You have about six decades of studio practice under your belt – of work, ideas, and concepts. Can you talk about what your work looked like in decade one, and then where you are now? And what was the idea you were pitching out to the Groot Foundation for this next body of work that you want to focus on?

Notkin

Notkin

Well, you know, the thing about my work is that it's always been fueled by my strong commitments to social justice and my life experiences. We are all wired differently, and we all have different histories. Our experiences form our passions, our commitments, and these should form the foundation for our innermost reasons for making our unique art.

I was born right after World War II, and my father was in the U.S. Army, in combat, a sergeant in charge of a howitzer platoon. Right after D-Day, he went through France, Belgium, and into Germany. It was not something he celebrated. He was proud to have been part of the larger forces that defeated fascism and Hitler, but he always felt that war was pure hell. He witnessed horrible things. It was hell. He never glorified it.

I also grew up among several Holocaust survivors in our synagogue and community, people who had tattooed numbers from the camps on their forearms. We were part of a reform synagogue. From an early age, on an annual Holocaust remembrance day, we saw films of the rise of nazism and its disastrous aftermath. I learned from the testimonies of the survivors in our congregation to always be alert, aware, and active. Being active was the main lesson.

I was fourteen years old during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. I begged my father to put a fallout shelter in our backyard. We lived on the south side of Chicago, just a few miles south of downtown, a major target. My father, Nathan Notkin, said to me, “And when we emerge from the fallout shelter, then what? Better to perish in the first blast.” My father was a very wise man. I distinctly remember that time and how incredibly frightening it was to be a child. And I suppose this early experience was the beginning of my opposition to nuclear weaponry. Pure insanity!

I was also a part of the Baby Boomer generation that was subject to the military draft during the Vietnam War years. Some of my peers and friends were drafted and sent to Vietnam. Some didn't come home. Others, the ones who did come home, were all changed, and not for the better – physically and mentally. And my generation was very active because of that. But we were no more altruistic than any other generation. It really had to do more with the survival instinct, which is strong in all cognitive species. Quite simply, we desperately wanted to survive.

All of these incidents were formative parts of my life and impacted my internal wiring.

I continue to see children suffering all over the world – just look at Gaza, my God! Throughout my whole life, it has been children and innocent people everywhere who have suffered horribly. War is insanity. You don’t have to experience war firsthand to comprehend this basic fact. Will we ever learn?

ROB

I can imagine the kind of language you grew up around, with your father returning from World War II. You’re describing the ideological tensions of the Cold War – democracy and capitalism versus communism, the arms race, the space race – an incredibly charged atmosphere. And as you were beginning your artistic practice in 1968, the Vietnam War was escalating; from roughly 1965 to 1969, the deployments surged. Many of the pivotal moments in your youth and early adulthood unfolded alongside major global conflicts. And as I think about it now, even the collapse of the Soviet Union occurred as you were moving into your professional life. It feels like many of those pivotal moments in your life have paralleled one war after another, back to back.

Notkin

And so many chances to really pursue peace. And every opportunity ending in failure.

I mean, you know, 1989 to 1991 was an incredible opportunity for the world to move forward towards a sane and sustainable future, and yet… But it's not the common people. Most of the people on our planet are basically good; it's the corruption and insatiable hunger for power of too many of the leaders who have wrested control of our planet’s nations. We just seem to allow the worst people to rise to positions of authority and power. But that's another story.

Getting back to the topic, we are all wired differently, and my art comes from a place that's deep inside me. I don't follow the zeitgeist. I've never felt a need to reinvent myself as an artist, and I find that that's not anything I would care to do. I make art from deep within me, from my innermost passions, from how I'm wired, from my personal history, and that's never changed. Nor will it change.

What has changed – which I think you mentioned – is how my work has developed from its beginning to the present. It's evolved – conceptually, technically, my processes have expanded in scope. I learned early in my career to trust myself, to be my own best self-critic. I look at the work every time I make something and ask myself: What works? What doesn't work? If I were to do this piece again, what would I change to make it better? I take notes, I do little thumbnail sketches. I keep all these notes and drawings in files. I follow my own example in what I tell my students: as an artist, I strive to be a perennial student. There's always so much more to learn, so much more to try, and so I try to do something different and a little better with each new series or artwork.

It rarely works, you know? I mean, I make a lot of failures, and if this were not the case, it would be an indication that I was not challenging my current set of limitations, not taking risks, not trying something new. You can hit on a formula that works every time, but you won't grow as an artist. And so getting back to your question, I know what I'm passionate about, where my commitments are, what I am trying to do as an artist.

It rarely works, you know? I mean, I make a lot of failures, and if this were not the case, it would be an indication that I was not challenging my current set of limitations, not taking risks, not trying something new. You can hit on a formula that works every time, but you won't grow as an artist. And so getting back to your question, I know what I'm passionate about, where my commitments are, what I am trying to do as an artist.

I guess part of it has to do with my early religious education, and the spirit of tikkun olam, which loosely translates from Hebrew as “improving or bettering the world.” It's a Jewish concept, but there are similar concepts in all religions – for example, Christ's teachings about taking care of the least among us. And I think as artists, we can use our art as a vehicle for betterment in so many ways. It's not just visual arts, it's all arts – it's poetry, literature, performance, film, music. That's the power of art, and it does make a difference.

ROB

In hearing you talk about failures, it's actually refreshing to hear you acknowledge that, because as an outsider looking in, I never see failure in your work. I keep you, in my mind's eye, as this pinnacle artist of craftsmanship and mastery in so many ways. Not only do you have technical mastery, which I'm sure was long sought after through failure and trials and tribulations, right? But you also have conceptual mastery. Speaking on the craftsmanship side: how do you think about the finish, the refinement, the precision as a visual language to communicate some of the narratives or conceptual concepts you're getting across? How do you leverage craftsmanship, or think of it?

Notkin

I think it goes way back. I mean, from the time I can remember, when I was even just a little kid, even preschool, I was always drawing and building things. And my parents always had blocks and things that I could construct with. I was always the class artist. I got excused from a lot of rote classroom busy work because I was always asked to do the class bulletin boards.

My dad was an immigration lawyer. He was always fighting the government and expressing his view that the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service) was a heartless government agency. (He would be even more outraged today!) I think I inherited quite a bit of that skeptical fighting spirit. And he had many Chinese clients who had fled the mainland through Hong Kong. Our family would go to Chinese restaurants many Sunday nights and be treated to a wonderful banquet. We also had many gifts of Chinese porcelain and cloisonne vases, ivory carvings, and silk embroideries, all so intricate and finely crafted. I was so fascinated with and inspired by these objects.

From second grade on, I won scholarships through the Chicago Public School system to attend Saturday morning classes for kids at the Chicago Art Institute. This was where I was first exposed to and became fascinated with surrealist paintings. We would go into the galleries and sketch from paintings. I chose artists like René Magritte, Salvador Dalí, Peter Blume, and Max Ernst. Many of them worked with such incredible detail, so I’ve always had that inclination. Much later, I entered the Kansas City Art Institute, determined to be a painter, with ceramics at the very bottom of my list of interests. Art school opened my mind to exploring many media and aesthetic directions, and clay came into my life in appropriate and meaningful ways when I was 20. It never left.

.

.

When I went to graduate school at UC Davis in 1971, I found myself in the heart of the Bay Area Funk Art movement. And I've said this before, but I'll say it again. You know, everyone criticized my work as being too small, tight, and precious. I spent about three weeks trying to be more gestural and to loosen my approach. God damn it, I was so miserable, I was just so unhappy. I thought, “This is not how I'm wired.” It was then that I realized, you know, fuck the zeitgeist! When everybody's thinking alike, nobody's really thinking. I thought this is not who I am as an artist. Art isn't about doing what everybody else is doing. It's about finding your own path. So I just decided I'm going to continue being small, tight, and precious. I just stuck to who I was from that point on, and when anyone criticized me for being too small, tight, and precious, I just took it as a compliment. They're saying I was different, and in the arts, that's a good thing.

When I went to graduate school at UC Davis in 1971, I found myself in the heart of the Bay Area Funk Art movement. And I've said this before, but I'll say it again. You know, everyone criticized my work as being too small, tight, and precious. I spent about three weeks trying to be more gestural and to loosen my approach. God damn it, I was so miserable, I was just so unhappy. I thought, “This is not how I'm wired.” It was then that I realized, you know, fuck the zeitgeist! When everybody's thinking alike, nobody's really thinking. I thought this is not who I am as an artist. Art isn't about doing what everybody else is doing. It's about finding your own path. So I just decided I'm going to continue being small, tight, and precious. I just stuck to who I was from that point on, and when anyone criticized me for being too small, tight, and precious, I just took it as a compliment. They're saying I was different, and in the arts, that's a good thing.

ROB

Listening to you speak about your father, I would describe his actions as a kind of moral resistance – standing up to the government and protecting others. In contrast, today we live in a moment when outrage can feel like entertainment and empathy itself seems politicized. In that landscape, how do you use art as a form of moral resistance rather than merely aesthetic commentary? Much of what you’ve shared points to this idea of resisting through art, especially when the work becomes political.

Notkin

Art can be effective as part of a moral resistance. It can be effective in expressing outrage. But I always tell students that if you choose the role of an artist who embraces social or political commentary, you must focus, first and foremost, on the art. The art is of prime importance. It is the quality of the art – aesthetically, conceptually, technically – that grabs your viewer. It is the art that carries the message. The corollary won't work. The message alone will not carry the art.

I tell students, focus on making your art strong, whatever that might mean. I think too many well-intentioned artists mistakenly think that “If I just have a message that everyone can rally around, that's going to make my art meaningful and relevant”.

It takes a great movie to ripple around the world in numerous theaters and have an incredible impact. Dr Strangelove is one of my favorite examples – especially the timing of its release in 1964, just two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the whole world was on edge, thinking this was the end of human civilization. Yet Stanley Kubrick created this brilliant and unabashed satire that pointed out the sheer insanity of the nuclear arms race. Everything about that film was so incredibly well conceived and performed – the writing, the acting, the cinematography, editing, etc. – and if it wasn't for the production quality and aesthetic brilliance, it would not have had such lasting success and become a true classic of American cinema.

ROB

ROB

Are you intentionally navigating that balance in your work – the tension between beauty and outrage? In Dr. Strangelove, there’s this careful interplay of narrative, current events, and satire, all crafted into a cohesive arc. When you make art, are you consciously assembling elements in a similar way to build a larger storyline, or does the work come together more organically? Are you tuning into something intrinsic and more subconscious?

Notkin

I'd say it's a little of all of that, actually. I don't work clay the way most people do.

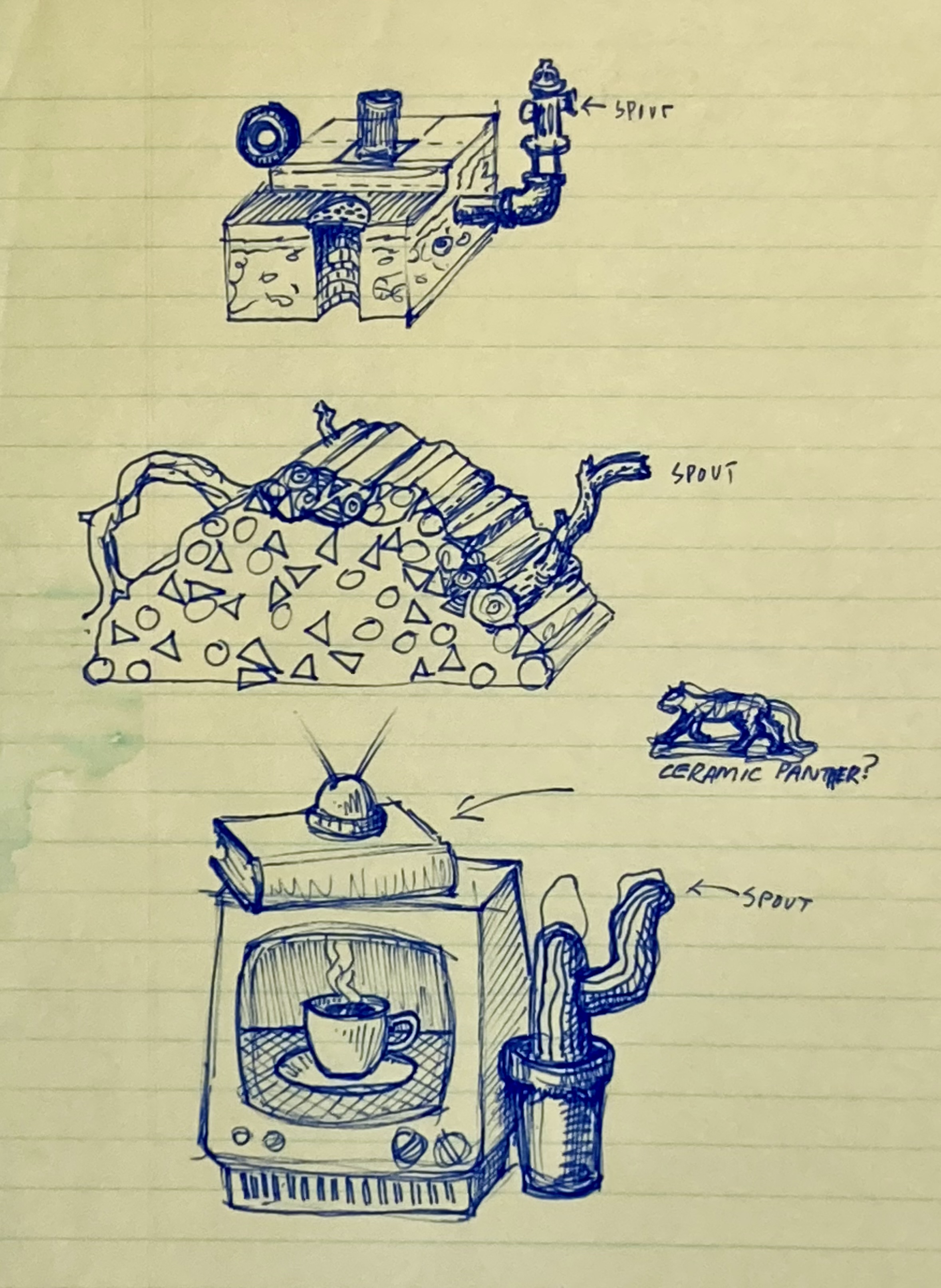

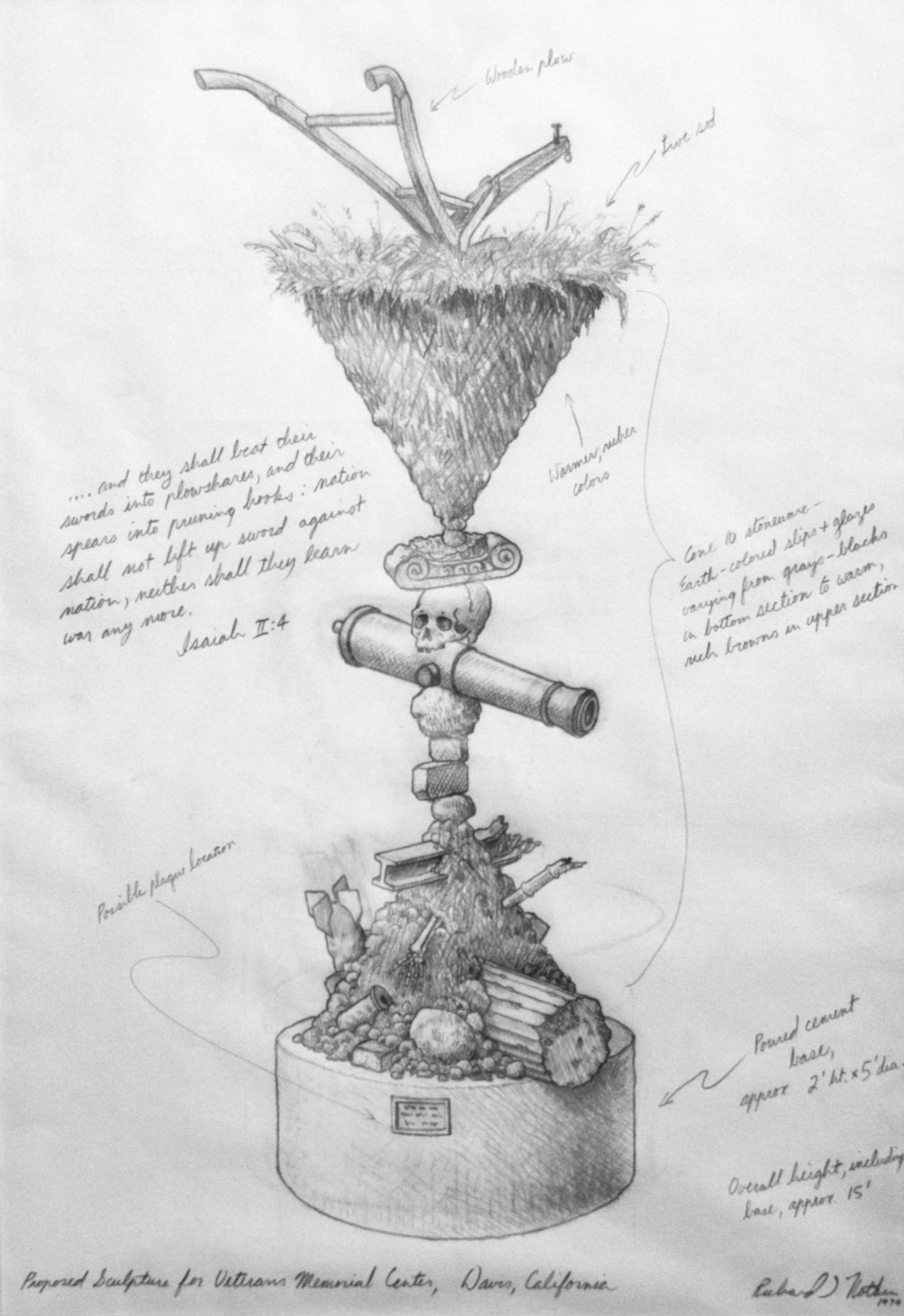

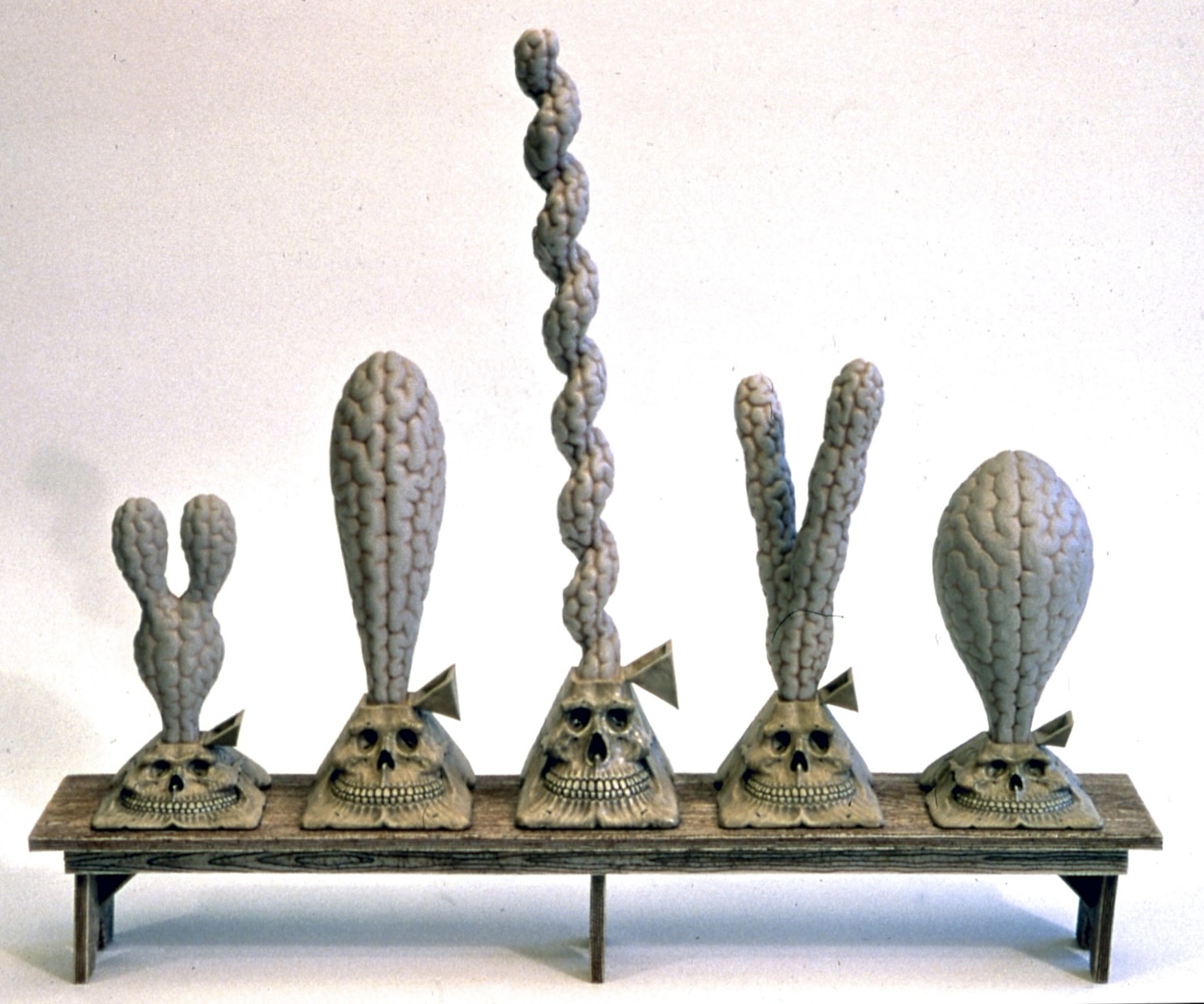

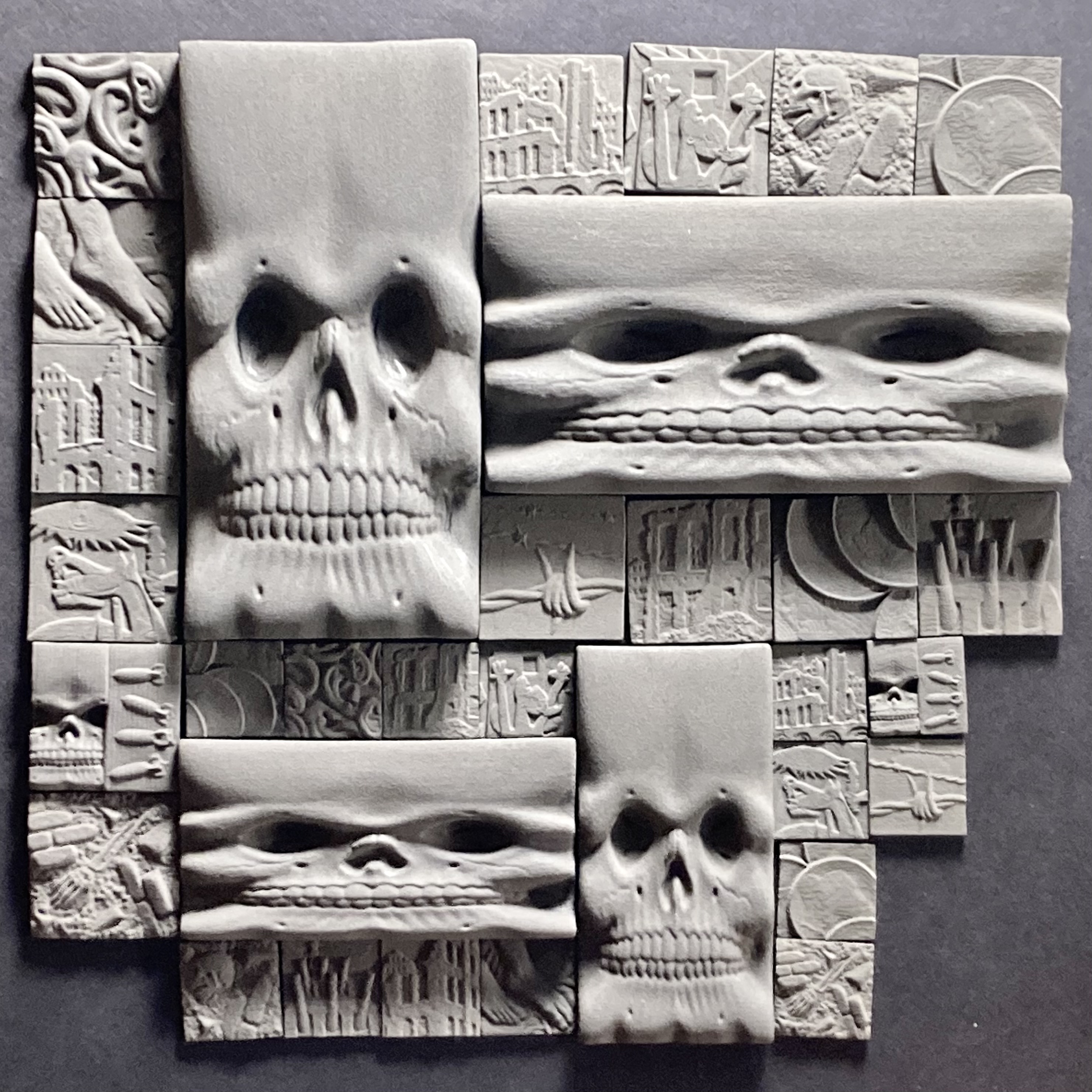

I’ve often stated that I make teapots unlike most ceramists, but more in the manner in which Detroit makes automobiles. I am a designer, tool-and-die technician, mold-maker, caster, and assembly-line worker. This applies to most of my work, not only the teapots. My pieces are mostly designed on paper prior to actually getting my hands into the clay, although a lot of the final decisions are made in the last stages of assembly. I do much thumbnail sketching, a lot of writing, and often over 100 quite small drawings, so I can consider many ideas and discard the less workable ones really fast. I work on all kinds of crummy papers with #2 pencils or ballpoint pens, so I'm not caught up in preciousness during those early fast-moving brainstorms. I don't want to think of my drawings as something I can show and sell because they're not meant to be commercial. They're just tools to develop my ideas. When I get a concept, I then attack it, and I search for related imagery, much like a poet chooses words. I then determine how to arrange these images into various relevant formats, how to juxtapose them as a group, and what visual devices will be most effective. I use a lot of Surrealist devices like interspersing the scales within one artwork: itty-bitty mushroom clouds, giant dice, ears of all sizes, etc., so that each of these disparate images and their relationships to one another creates a narrative. I'm not a Surrealist because Surrealists were exploring the subconscious. I'm trying to get people to decipher the images and how I put them forward in a conscious way. So, it's not Surrealism, but I've learned the tools, the devices of the Surrealists. So in a sense, I'm creating a visual poetry, a poetry of three-dimensional imagery.

ROB

I’m so glad you said that, because when I look at your visual language and interpret those cues and triggers, I find myself deciphering the work the way I would approach a poem. There’s a sense of flow from one piece to the next, and the meaning shifts depending on the day. It’s a joy to linger and wander through the work, letting my mind drift into the spaces the images suggest.

I imagine that many of these individual devices originate from a specific point of inspiration, perhaps a current event at the time the piece was made. But as I was looking back at some of your earlier work, including pieces at the Everson Museum of Art, I was struck by how your objects feel both timeless and timely. Even knowing a work was created in the 1970s, it still feels immediately relevant today. So I wanted to ask: Do you think ahead about ‘future-proofing’ your work when it’s tied to a specific political moment? Perhaps that’s simply the nature of history – cycles repeating so that earlier pieces gain new resonance. But as you’re making, do you consider this balance between timeliness and timelessness?

Notkin

Fired ceramics, because of their nature to survive the ravages of time and the elements (some of the earliest known human creations are ceramic), simply don't rot or disappear. We recognize links from all cultures and all eras of human civilization, the similarities of the most ancient pottery, whether it's from Asia or America or Africa or wherever, from all eras of human history. There is an underlying logic regarding the similar functional aspects and primal technologies – the basic firing pits, commonly accessible glaze materials like iron. But the repetitive decorative patterns from distant continents and spanning thousands of years reveal how the creative spirit is so intrinsically linked in all human beings, in our DNA, but that's a bit of a tangential point.

The point I would like to reiterate is that ceramics have the capability to transcend time beyond just their physical survivability.

In terms of the timeliness of the message, and regarding future proofing, I'm always referring to works of art which I consider the very highest examples, the high bars in artworks in the realm of social/political commentary. I'm looking specifically at such classic works with anti-war messages as Goya’s Disasters of War etchings. Actually, the Disasters of War suite was a title posthumously added to these etchings. But my God, what incredibly impactful imagery! And Goya’s titles for each individual etching really influenced me, because they're all so pointedly ironic. Of course, there's also Picasso’s painting Guernica, depicting in the artist’s inimitable style the bombing of that previously unknown village in Spain by Hitler’s Luftwaffe in collaboration with the fascist dictators of Italy and Spain. And the sheer strength of that painting, the scale, the imagery! I've appropriated a few details from that painting in some of my relief tiles – the screaming horse, the wailing woman. They're so iconic and timeless. And you know, the fact that this happened in 1937 in a rather obscure village. Who would even know of Guernica were it not for that masterpiece of oil paint on canvas? When an artwork is so profound and impactful, it becomes timeless. It is never easy to create an artwork that is conceptually and aesthetically strong, but when successful, that artwork can carry a profound message and be timeless. And that's the potential power of art.

ROB

You’ve spent your career making work that warns against the repetition of history, while also drawing on artists like Picasso, whose work stands as an artistic record of war. In today’s fractured political climate – this is more of a political question than an artistic one – do you feel we’ve learned anything from the past, or are we simply witnessing another echo of it? I know this sounds bleak for an interview, but when I think about Picasso, about the present moment, and about all the artists across time who have documented the horrors of war, nationalism, and the erosion of truth.

Perhaps this is too heavy for the interview...

Notkin

Notkin

Oh, I don't think so. I mentioned before that my generation wasn't any more altruistic than any other. We were fighting for our survival. We didn't want to go to a war that we saw no purpose in fighting. At least for my parents and the parents of those in my generation, there was an existential threat, a tangible reason for fighting fascism and the horrors that were already happening in Europe and Asia.

There is a point where that basic instinct for survival kicks in, and I don't know what it is going to take, but we're seeing growing evidence on a daily basis, whether it's more frequent and catastrophic climate incidences – hurricanes, tornadoes, or the expanding belt around the equator where lands are becoming more arid and less able to sustain crops. Perhaps the increasing incidence of famines that are occurring and the resulting forced migrations – people fleeing – from where they can no longer sustain a life for their families. While this is currently impacting people in less developed parts of the world, there's a growing awareness, especially among our younger generations, with new emerging leaders like climate activist Greta Thunberg. And the nuclear arms race, which is beginning to ratchet up again, is nothing more than a game of Russian Roulette that can only end in one way. Frankly, it is not a matter of “if”, but of “when.”

There will eventually come a time when these multiple existential threats will become so apparent that an international youth movement will arise in protest and shout, “Enough!” Many generations already believe it is long past the time to say, “Enough!” Fortunately, young people are the only expanding demographic. I only hope time is still on their side.

Artists have always had a major influence on youth. Consider the popular anthems of all generations, and the musicians my generation listened to as we protested in the streets: Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and many others. Artists can have an incredible impact on this world. And I truly believe that.

The reality is that things will get worse before they get better, and that's very unfortunate. But I'm an eternal optimist. If I weren't, I wouldn't be making the work I make. You know, people sometimes say to me, “Notkin, your work seems so dark. You must be quite pessimistic.” Well, if I really were pessimistic, I wouldn't bother.

ROB

ROB

In a similar vein, when I think about the next generation of artists who will eventually stand up and say “Enough!” my mind goes to the ways people consume information now – news, social media, and everything in between. There’s a normalization of violence and a growing acceptance that our environment is failing because of our collective habits. How can artists create work that cuts through this desensitization and rekindles a sense of urgency – an ethical urgency? You’ve maintained that conviction throughout your career. But how do you imagine emerging artists breaking through that numbness today?

Notkin

Well, I think we must recognize, first of all, that none of us is going to make the teapot that saves the world. (Laughs…)

It is a collective effort that involves all of us. I believe Gandhi said, and I'll paraphrase, that “enough grains of sand can stop even the mightiest of machines.” And I think that's what artists of all media and types have always done. Artists have illuminated that there's a very creative side to the human species. Artists have always been the light in opposition to the darkness of our more destructive potential.

My artist statement starts with the sentence “We have stumbled into the 21st Century with the technologies of Star Wars and the emotional maturity of cavemen.” We know that we could utilize those incredible technologies toward greater purposes, and yet…

So, I think one thing that artists can do is recognize that we constitute a potential collective force, and we need to all work together. We can't erect barriers, but sometimes we do. In current artworld dialogues involving a somewhat extreme woke viewpoint, there are arguments over appropriating imagery and symbols seen as specifically inherent or “owned” by a race, religion, nationality, etc. Do you have permission to use my particular group’s symbol or can I appropriate from your imagery? I happen to be Jewish, and I come from a subset of people who survived centuries of antisemitism, leading to the nazi-era Holocaust. My grandparents fled Soviet pogroms, other ancestors fled the Nazis, and some perished in World War II. Yet why would I tell anyone that they couldn’t use symbols from Judaism or the Holocaust? Genocide can affect anyone from all branches of humanity, and it's affecting people all over the world right now, in Sudan, in Myanmar, in Gaza, and elsewhere. I would hope that we can drop our sense of proprietary ownership of imagery. If you need images from the Holocaust to protest genocide of human beings anywhere, please use these images if they strengthen the narrative of your art. I use the images of the mushroom clouds over Nagasaki and Hiroshima, but I'm not Japanese. I'm an American. Hell, we're the ones who dropped those bombs, to our lasting shame. But, my God, I must use these symbols in my opposition to these tools of sheer madness. We need to realize that we're one human race, that we're all in this together. Let's not argue over who controls or owns which images. Let's share these images. Let's share because we share our fate on this planet.

What I'm advocating is that the struggle for sanity, for peace, for survival on this planet is a shared struggle amongst all of us. I'm all for diversity, equality, and inclusion, but when we start erecting walls or creating silos to basically isolate our own specific group, we're hypocritically acting in the opposite direction.

ROB

I hear you.

In that same vein – and this is admittedly a selfish question on my part – I often feel torn between activism and making. It’s something I struggle with personally. Your comment about pessimism really resonated with me: “If I were pessimistic, I wouldn’t make this art,” yet you still hold on to hope. For those of us caught between being active in our communities, civically and otherwise, and also tending to our studio practices, do you have advice? How can artists who want their work to speak clearly – who want to expose social injustice – find that balance between confronting hard truths without slipping into pessimism?

Notkin

Well, the one thing I never wanted to be perceived as is a kind of Billy Graham evangelist-style persona. I am not on an evangelistic mission as an artist preaching to other artists to follow the route of social and political commentary in one's art. I feel that if a person is really motivated and feels that that is their life's calling as an artist – great, do it!

Every creative act is a positive statement in itself. You know, an abstract painting – a visually/intellectually compelling abstraction – can lift people's spirits. A melodious mind-capturing musical composition with no words at all. I mean, listen to Mozart. There are no politics in the layered cascades of notes, but what a spiritual ride it can provide. The sheer force and power of human creativity!

Every creative act is a positive statement in itself. You know, an abstract painting – a visually/intellectually compelling abstraction – can lift people's spirits. A melodious mind-capturing musical composition with no words at all. I mean, listen to Mozart. There are no politics in the layered cascades of notes, but what a spiritual ride it can provide. The sheer force and power of human creativity!

André Malraux said, “Art is a revolt against man's fate.”

And it really is. I mentioned a little earlier in this talk that art is the light against the darkness. It illuminates the creative side of the human species, the creative part of our souls, that there's something worth preserving. If you're a functional potter, make the best damn functional pots you can. You know, pots that really work, that feel good in your hand when you're using them, that are beautiful; that's a role worth pursuing. I really believe that every creative act is a positive contribution to our collective humanity.

But there is another role we all should play: We all have a life to live outside of our studios, outside of our roles as artists, and in that role we must strive to be the best person we can. Tikkun olam again – the improvement and betterment of the world. Love your partner, love your family, and bring your children up with good values. You know, if you feel so moved, march in the current anti-authoritarian protests, write letters to the editor of your local newspaper, call your congresspeople, volunteer at your local food bank. Or just have respectful discussions with your colleagues, neighbors, and friends, of all political persuasions. Listen to people, no matter how different their opinions might be. You might learn something illuminating about their perceptions, and they might listen to yours, too.

In 2018, I gave the closing address at NCECA, and in the end, I said, "You know, there's probably a number of people out there who are thinking, 'Oh, come on, Notkin, can art really save the world?'" And then I said, "Well, frankly, that's the wrong question. The real question is, 'Can art make a difference?'" And to that question, I have an unequivocal answer, and that is, it already has.

And I believe that.

When I teach a workshop, I ask my students, if you don't think that art makes a difference, try to imagine a world with no art at all: no music, no literature, no visual art, no film, no architecture, no art of any medium or genre at all. Could the human species and civilization have survived such an aesthetically and culturally sterile environment?

ROB

I love that – truly. It’s such a grounding way to think about the bigger picture, and it helps reaffirm the “why” behind the need to keep making.

Circling back to our earlier conversation, I was hoping you could share a bit about your next body of work. What ideas are you exploring for the project that the Groot Foundation is honoring? Can you give us any insight into what this new body of work might look like or what your goals are for it?

Notkin

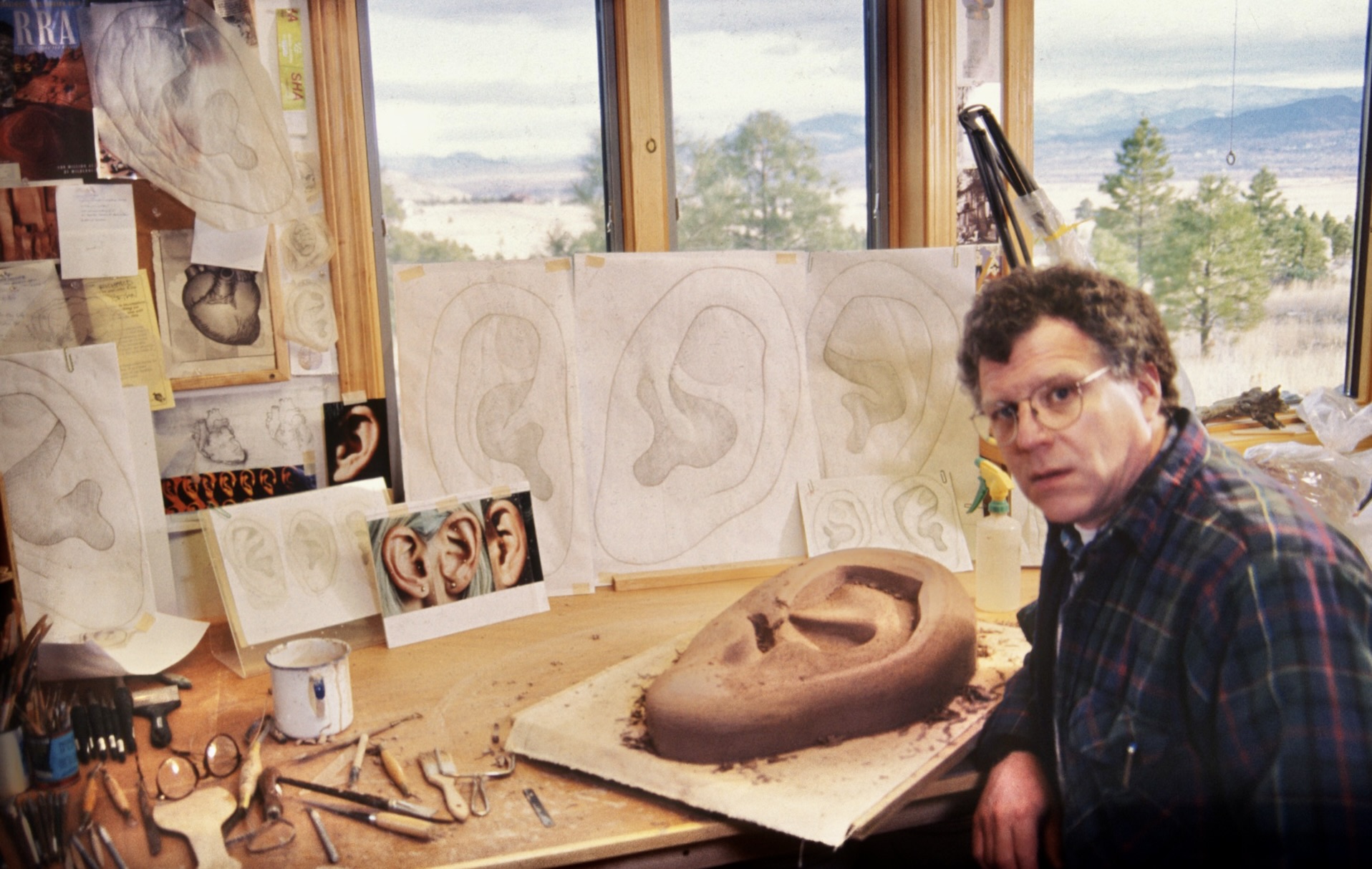

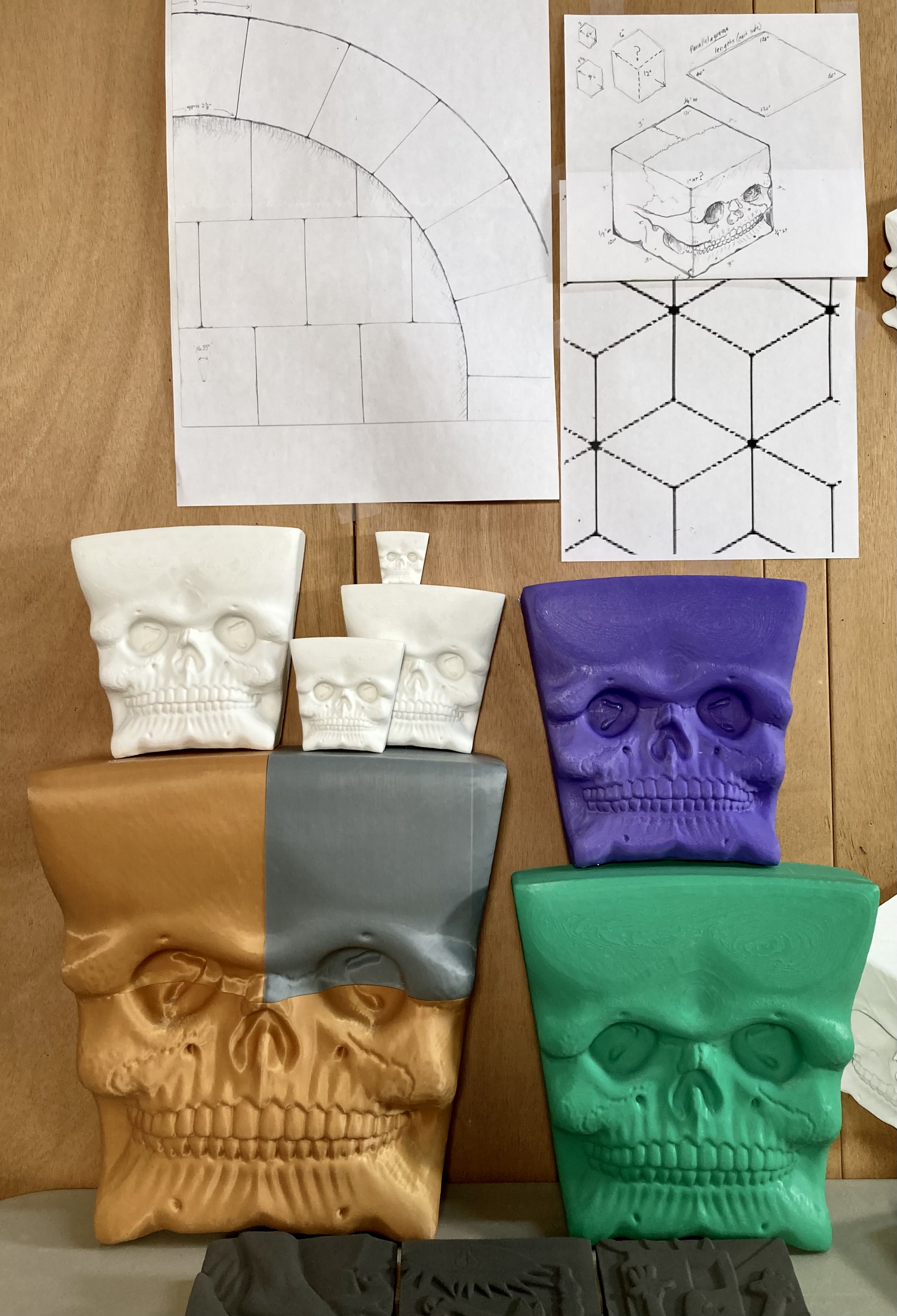

Well, a few years ago, I started having some age-related illnesses that made me realize I couldn't physically do everything I could do when I was younger, and I was experimenting with three-dimensional digital printing. This actually began about fifteen years ago at Haystack Mountain School of Craft with some very primitive equipment in their early Fab Lab. I continued experimenting with these technologies at the Kansas City Art Institute’s Beal Studios with my great digital mentor, Aldo Bacchetta, who assisted me in designing and printing the prototype models for the Trumpolini Series. I have continued working with digital fabrication experts at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, when I was a resident artist in 2022. I created some new designs for prototype models at the Kansas City Art Institute in 2023, again with Aldo. Last year, I was in California for a month, working with digital maestro Matt Mitros in an intensive digital ceramic artist residency program (unfortunately, now ended), pushing into new aesthetic and conceptual territory for my designs. I've taken a lot of my former sculpted pieces, mostly tiles, but also some three-dimensional pieces, and digitally scanned them for use in the Rhino 3-D design software program. With the assistance of the techno-wizards in these various venues, we then altered the dimensions and manipulated each piece through distortion, stretching, twisting, etc. Some of my tiles were also reconfigured as arches, and I have all these new prototypes to work with. I'm making molds of these newly generated models, things that I would now have great difficulty doing by hand. I could have done this work the old-fashioned, analog, by-hand way easily when I was younger. And I have discovered an added benefit: As with molds, these new technologies have become another time-saving device.

I'm still working with my own designs, my original designs, a philosophy I adopted early in my mold-making learning curve. I also remain excited about incorporating new technologies. You know, I’m trying to disprove the old adage, “you can't teach an old dog new tricks.” I'm personally embracing the notion that artists should remain perennial students. Something I've always enjoyed is absorbing new techniques, new processes, and new ways of working throughout my career. This has really made my studio a complex mess, because I work with all different clays, all different processes. So much equipment, so much storage for all these tools, molds, materials, etc.

I'm still working with my own designs, my original designs, a philosophy I adopted early in my mold-making learning curve. I also remain excited about incorporating new technologies. You know, I’m trying to disprove the old adage, “you can't teach an old dog new tricks.” I'm personally embracing the notion that artists should remain perennial students. Something I've always enjoyed is absorbing new techniques, new processes, and new ways of working throughout my career. This has really made my studio a complex mess, because I work with all different clays, all different processes. So much equipment, so much storage for all these tools, molds, materials, etc.

I have this huge library of imagery encapsulated in molds I have made during the past fifty-seven years. While I first began my experiments in mold-making with found objects, I soon discovered I had become primarily a proficient mold technician, not an original artist/designer. Following this revelation, which occurred about a year into my working with molds and slip casting, 99% of my molds were cast from things that I designed and created, you know, things that I originally carved in clay, as opposed to found objects.

.

.

Based on the range of my previous work, experiences, and concepts, I am now moving forward into new territory. I envision an ongoing installation, a series of interlocking, three-dimensional pieces and overlapping sections of murals, inspired by my previous tile murals, but very different and more organic, a bit like crazy quilts. These will not merely be confined to rectangular/square tile formats, but will allow for broad curvilinear forms to wind their way over and through various other images and patterns. There will be areas of arches within arches to create illusionistic perspectives of receding space. And after a twelve-year period of mostly monochromatic work – the Yixing Series of unglazed stoneware teapots in the 1980s and 90’s – over the past three decades, I have added color to my work to enhance the narratives because all colors have particular associations and connotations. The color red says something, especially in the context and format in which it is presented. Yellow and black diagonal stripes express an immediate, universally comprehended warning about approaching dangers. And so all these ideas, styles, and approaches that I've learned from the past almost six decades of art-making are coalescing into this final piece.

I don't have a full vision of the fully completed installation in my mind, nor do I expect to ever finish it. I just imagine all these interlocking fragments and how they can relate and how they can be arranged in different spaces in various ways. Some of the mural sections on the walls will have parts that extend three-dimensionally to interact with some of the sculptural pieces. There will also be a sort of “loose grout,” bits of filler between some of the three-dimensional elements, like the stoneware ears that I did for the Legacy series. Other stone-like elements in this aspect of the installation will utilize images I have created in past work: hearts, fists, brains, etc.

I don't have a full vision of the fully completed installation in my mind, nor do I expect to ever finish it. I just imagine all these interlocking fragments and how they can relate and how they can be arranged in different spaces in various ways. Some of the mural sections on the walls will have parts that extend three-dimensionally to interact with some of the sculptural pieces. There will also be a sort of “loose grout,” bits of filler between some of the three-dimensional elements, like the stoneware ears that I did for the Legacy series. Other stone-like elements in this aspect of the installation will utilize images I have created in past work: hearts, fists, brains, etc.

To summarize the narrative, I intend this installation to interweave all the various themes that I've worked with over the entire span of my lifetime as an artist. It will be my final statement, my final act of activism, so to speak…

And finally – and this is the most significant conceptual aspect to this piece – there is only one deadline regarding its finish, and that's my lifeline. A final, literal “dead” line. When I’m gone, it's done.

Which means that it will have unfinished edges, and that, to me, is the most significant visual clue, the subtle ironic twist of the piece. Because this is a work that's pleading for sanity, for peace. It is a plea that will certainly be unfinished when I die, and a real-world quest that may be unfinished for generations or for as long as human beings continue to survive on this precarious planet. It's a struggle that has existed since the dawn of human civilization, and no singular artist is going to solve these dilemmas.

It's my way of stating that I'm part of a long collective struggle, and I'm passing the ball on to future generations of artists. When I'm gone, there will be unfired edges to the installation’s numerous elements. I intend that to be part of the piece. That's my vision. And you know, whether I live for only the next one or two years to create it, or another ten or fifteen years, or whatever unknown quantity of time I have left, I don't know exactly what it's going to be, as the idea of a finished piece is irrelevant. I have strong ideas about what all these different parts are going to look like, and my visions keep evolving. It’s invigorating and personally inspiring to have such a vision, a purposeful commitment, something to live for, to keep one’s spirit from atrophying, to keep you moving forward in your chosen work.

I’ll share an anecdote that I read about a person who walked into Albert Einstein's office and glanced at his desk. It was covered with piles of papers and books and this and that. And this person looked at Einstein and said, “A cluttered desk is a sign of a cluttered mind.” And Einstein looked back at him and said, “What then is an empty desk?”

When I was younger, I was extremely anxious and concerned that I would die with the best ideas for art still in my head. And now I think, “Far out!” There are so many ideas for unfinished art stuck in the crevasses of my convoluted grey matter. I'll never get them all out, but it gives me something to keep working toward. This is the fuel that propels me forward while I am still alive. And as for those ideas that are still trapped inside when I pass? Well, who the hell's gonna know?