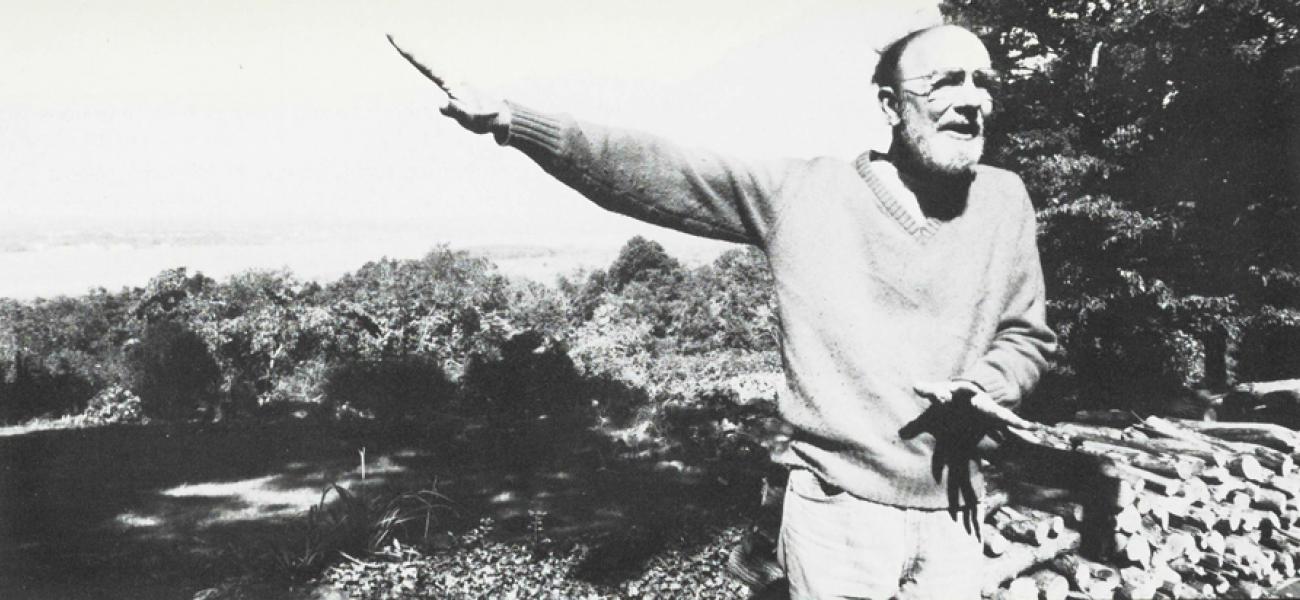

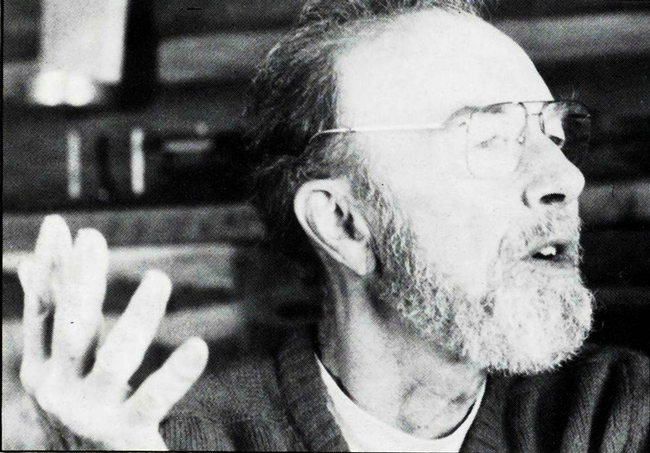

Pete Seeger on the Hudson Valley

This article originally appeared in Volume 12, Number 1 Winter/Spring 1983.

“The meek shall not inherit a poisonous garbage dump."

If you look at the base of the Palisades on the Hudson River just south of the George Washington Bridge, you can see where the dark rock of the Palisades ends and the red sandstone begins. That black rock is an extrusion between two layers of sandstone. This hard basalt was crystallized at right angles to the crest so it was sheared off when the glaciers came down. The crystals that were left look like log fortresses, which we now call the Palisades.

Storm King Mountain, where I live, was formed about a thousand million years ago. The glaciers were a fairly recent advent—only about a million years ago. Previous to the glacial period, the Hudson probably flowed down to the Delaware or Hackensack valleys. But the glaciers punched a hole through the Appalachian mountain range, which allowed the Hudson to penetrate the range. Thus on one side of the river you can see Storm King Mountain and on the other Breakneck Cliff, but they're really parts of the same mountain.

Once at the age of seven I painted a picture of a beautiful valley in which a huge ugly factory crouched like a giant. Through its jaws filed a long line of people being eaten alive by this monster. I still feel this way. I think of Frank Lloyd Wrights statement: "Cities are mantraps." (And woman-traps too.) People go to cities thinking they'll make some money and eventually be able to leave, but they get trapped there. They don't make money, they never do leave, and they spend their lives struggling to make ends meet.

In 1962 I read Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring. As a result I had to admit that one couldn't postpone solving the problems of our environment until the basic organization of society was changed. If we ignore the problem of our air and water, we might help the meek inherit the earth, but what they would inherit would by then be a poisonous garbage dump.

After reading Silent Spring I was one of many people wringing their hands. Now, I have always loved American history and, while reading a book on old sloops, I said to the friend who had loaned me the book, 'Wouldn't it be great to build a replica of one of these old boats?' He took me up on it, and before we knew it we had a nonprofit organization formed and were raising money to build a sloop.

We showed the plans at one point to a millionaire, who could have afforded by himself to build the boat. He said, "It's a lovely ship. But why do you want to sail the Hudson? I sail in the Virgin Islands." Unwittingly, he had given the best reason to build the boat-saving a great river, a cause worth fighting for. Thus building a replica of an old boat was not a frivolous adventure of a few rich people but something that thousands of people would want to share in. We went public.

The boat was designed and built in Maine by a man who did research in the Smithsonian Institution and in Connecticut's Mystic Seaport. We were encouraged in the project and were provided with detailed plans. There were no plans, however, for the boat's rigging, so the boat architect found a 35mm slide of a rigged sloop and traced its rigging using a magnifying glass.

When the ship was finished, there were strong arguments about how it should be run. Some wanted to put uniforms on the crew while some wanted to run the crew in a completely laissez-faire way. Some wanted the boat to be an historical project, and some an ecology project. When things simmered down it became a combination of both. We voted to make the purpose of the Clearwater (as we called the sloop) helping to restore the river and its shores.

The Clearwater is a highly visible symbol which says: Somebody is trying to do something about the river. Part of the problem is keeping our struggle visible. The Clearwater has done this by serving as an object of beauty like a temple. It is a supremely beautiful construction of wood, canvas, and rope. People look at it from the shore and say, 'That's the Clearwater! Those are the people trying to clean up the river!'

The river has gradually been improving. We can't claim all the credit as we are just a part of a nationwide revulsion which took place in the late 1960s-and early 1970s against pollution. The Federal Clean Water Amendment of 1972 was passed as a result of this movement. It is a three hundred page document, incredibly complicated, which serves to establish what can and cannot be put into our water and sets up schedules for wastewater plant construction. The mid-Hudson is now swimmable, thanks to these treatment plants. We also raise money and hire lawyers and scientists and along with other organizations go to court to stop polluters. We've joined with the fishermen of the Hudson River and have gotten polluters to stop putting PCB into the river. We're pushing for more sewerage treatment plants both down river and upriver.

Seven years ago we decided to have a big gathering. The Clearwater Organization appointed a committee, called the Hudson River Revival Committee, of fifteen local people who meet all year around to plan this June event. Potters, woodworkers, weavers, boat builders, environmental exhibits, solar energy exhibits-every group has its own committee. One of the most important committees is the Litter Committee-ten thousand Americans and not a cigarette butt left on the ground!

The revival idea is nationwide and is a countercurrent to mass production, the mainstream of American life. People are saying: "Wait a minute, I want to do this by hand!" Whether ifs learning to play the guitar or learning to make pottery, it is a significant phenomenon. The higher standard of living which mass production gave us did not result simply in more people wanting to become consumers; they wanted also to be doers.

Revivals fail when people fail to appreciate the depth of an art form. You don't learn to play bluegrass banjo in a month or two. If you're lucky, you'll still be learning fifty years from now. Americans have this special weakness: they want to do everything in a hurry. They'll buy a thousand dollars' worth of crafts equipment and then, if in a year their dreams don't come true, they'll put it all in the attic. Just because its folk art doesn't mean its not complicated! I often point out that in music the simplest instruments are the hardest to play.

I'm tremendously impressed with the resiliency of the American people, but I'm not optimistic as we go into the next decade. Americans tend to underestimate the difficulties ahead of us, as probably does the whole human race. If people knew ahead of time how difficult it was to raise a family or put up a house, they would probably be too discouraged to start. Recently I went to a convention of biologists and met some healthy young people who have decided not to bring children into the world. They said they know what shape the environment is in and feel discouraged they haven't gotten the rest of the world to listen and change. But I told them that I've seen people's heads turn a hundred and eighty degrees within a few hours. Sometimes music has done it. Sometimes a great oration has done it. Sometimes reading a book has done it.

Pete Seeger Box 431 Beacon, NY 12508

Want to read more from this issue? Become a member today!