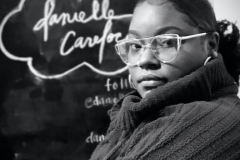

Before I Can Talk About Clay

I couldn't find the inclination or inspiration to do that, especially when it feels like the world I am living in is still in flames.

2020 was challenging for everyone, but especially for Black and Brown folx living across the US and the world. Whether it be from increasing job insecurity and/or job loss, higher rates of COVID infections and deaths, or state-sanctioned violence that continues in the midst of a worsening pandemic, the effects of systemic, economic, and interpersonal racism have finally started to boil over. While the art industry prides itself on being progressive, the same racial disparity and injustices we see playing out in the less isolated areas of our daily lives continue to be prevalent within the art industry as well. Any substantive change that a society needs has to occur at every societal level – that includes within the institution of ART.

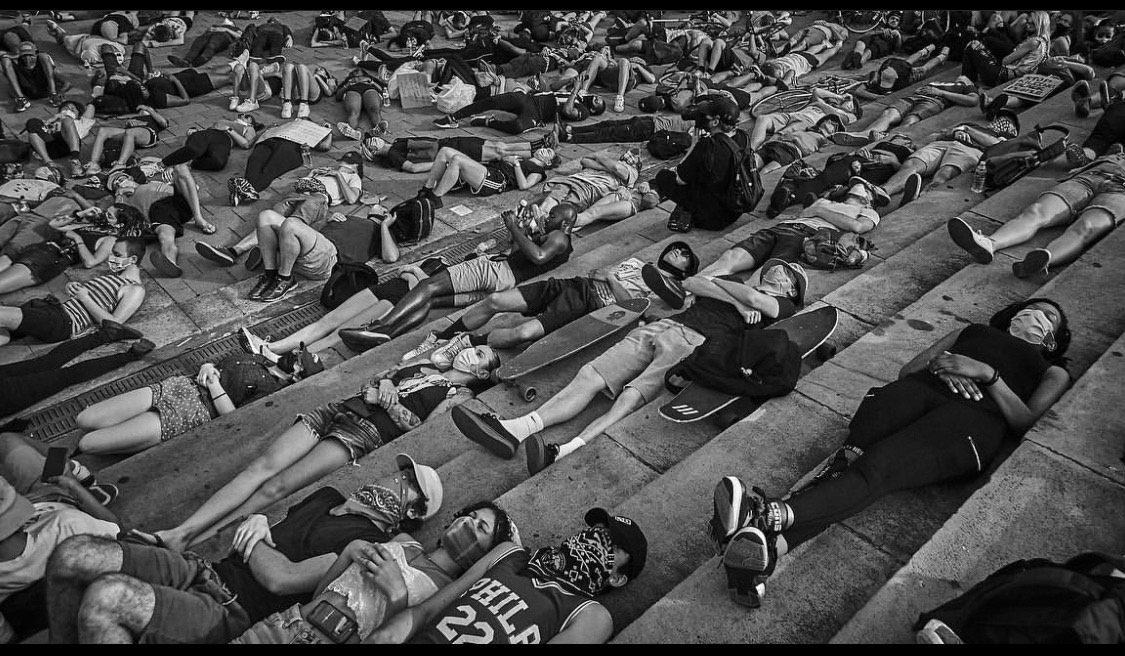

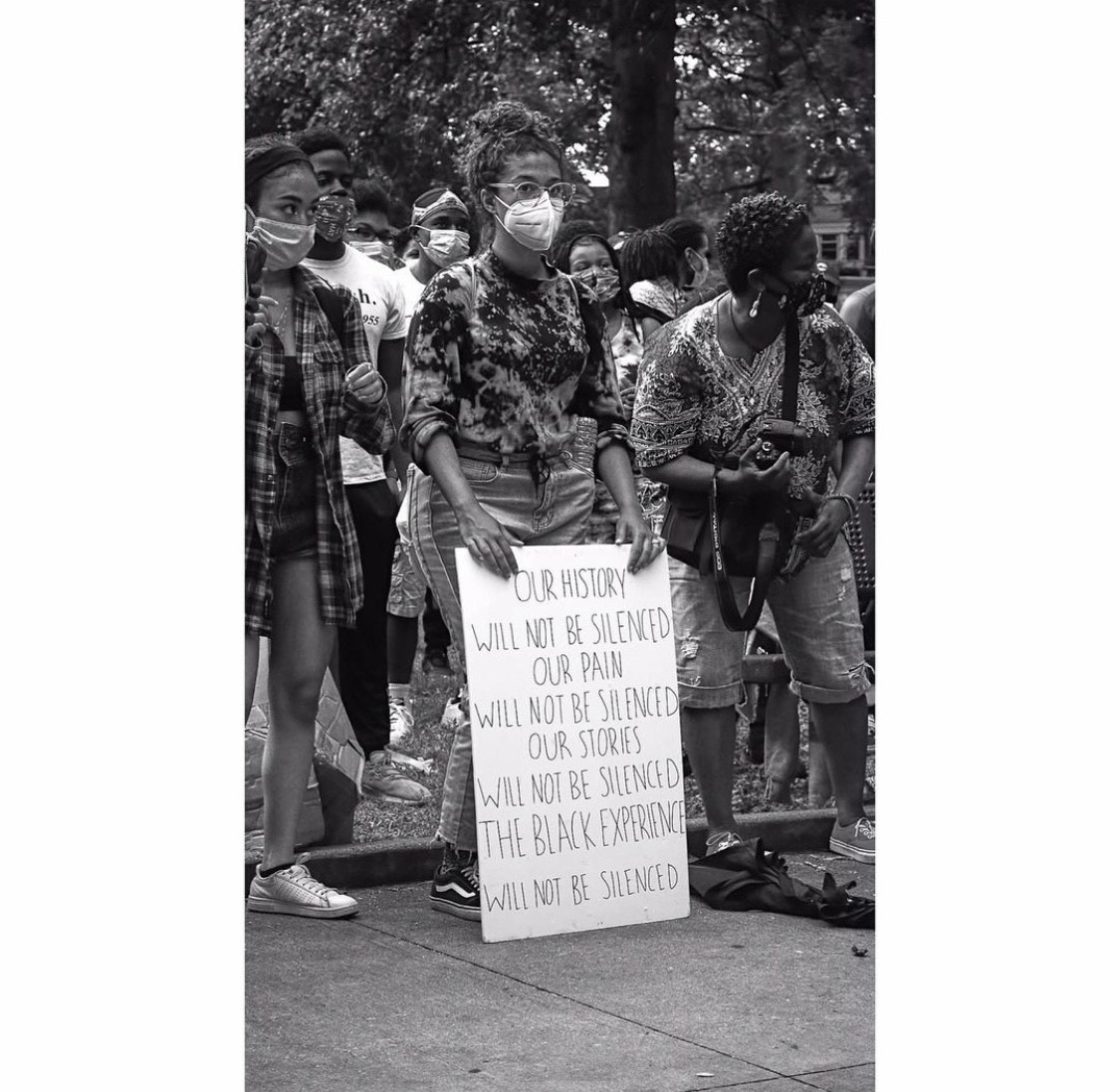

Historically, Black and Brown people have always suffered disproportionately from an oppressive status quo. This pandemic has only heightened the inequity that was and that, unfortunately, continues to exist. I'm sure many of you reading this have heard of or maybe even participated in the protests that erupted last summer following the violent and disturbing murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and many others. You might even have signed a petition or two. However, there is a chasm that stands between the needs of the people and the responses from government and institutions.

Solidarity is not and cannot be enough.

Black and Brown people have been begging for equity and respect, begging to be released from the proverbial and literal foot on their necks, begging for their humanity and quality of life for far too long. Our cries have become rhythmic – the elevator music that plays softly in the background while those in power blithely enforce policies and actions that continue to adversely affect the physical and material lives of Black and Brown folx.

While acknowledging that the struggle for justice and equity and standing in solidarity are good things White people can do, let me be very clear – good intentions do little to change the material experience of Black and Brown lives.

We know when we look a bit closer at the art industry, into the niche of ceramics, racism and inequity are no strangers here either. The majority of ceramics studios and art institutions are predominantly white. They often do not reflect national demographics and, more often than not, have a distorted representation and understanding of their direct communities. I have worked in a ceramics studio where that disparity was palpable. While most of this particular studio’s outreach engagements were attended predominately by Black and Brown community members during my time there, the in-studio student population was the exact opposite and to the best of my knowledge that disparity remains. Currently, at this particular studio (which is positioned in a diverse area), there are only five Black or Brown people of the fifty-four artists, instructors, leaders, and board members associated with the organization. Just 9.25%, where over 40% of the U.S. population and an estimated 50.46% of the local population are non-white people of color.

The scarce and tokenized inclusion of the culturally underrepresented in lower-level roles at art institutions nationally does not translate into support, cultural competency, community, or safe access. It also does little to change the livelihood of the Black and Brown staff working in these institutions, who are, in the midst of this pandemic, being furloughed or dismissed at alarmingly disproportionate rates.1

Moreover, where there's a lack of adequate representation, (Black and Brown leadership, safe access, and support) there also comes an absence of cultural competency, understanding of nuance, and implicit bias. These deficits manifest in many ways and are detrimental to all parties, impacting the overall health of the organization and every individual within it.2

Unfortunately, this outcome isn't an anomaly or central to me, but a normal experience for Black and Brown people – not only in ceramics or art institutions, but across industries – especially in places where there is little diversity in leadership positions.

Many facilities would like to believe their missions and the work they do are for all people. Unfortunately, that belief doesn't mean all people ARE treated equitably, feel included, and are supported in their full being, or can safely access these spaces.

Intent doesn't equate to impact.

Our society has begun to come to understand and accept the difference between intent and impact in regard to sexual harassment. It is time to achieve the same level of understanding regarding racism.

Combating racism doesn't begin and end with hiring for the sake of diversity and inclusion. Efforts need to go much deeper than that and need to assess the barriers in place that account for this disparity. Cultural institutions, studios, and workplaces need to be set up to strive continually for anti-racist practices and policy, as it is not merely a moment you arrive at but an ongoing effort. Undoing systems that have been set in place, designed over the past four-hundred-plus years, will not be accomplished in a summer's time. In 2020 we saw symptoms of a larger issue that had been present long before the amplification of the calls to action that began in June

and July. Although 2020 was a challenging year that exhausted us all, 2021 needs to be the year that we move forward to create impactful change. The changes that we need – the anti-racist ideals that we should all strive to embody – require deliberate action, attentiveness, courage, discomfort, conflict, and ultimately a release and restructuring of power.

RESOURCES

1. Cultural Competence: An Important Skill Set for the 21st Century. This study by University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension is referenced twice in the article above and is highly recommended by the author as a starting point in understanding how we perpetuate racism and tone deaf micro-aggressions in our daily lives. The article details steps toward cultural competency.

2. Racial and Social Justice 101. This recorded webinar, taught by Ericka Hart, M.Ed., acts as an educational resource for organizations and individuals seeking to deepen both their professional and personal practices toward centering those who navigate society from its margins. The author has taken and personally recommends this webinar.

3. Accomplices Leadership Institute created by Arts Administrators of Color Network, "...the accomplices of the Arts Administrators of Color Network actively create agency to use their privilege to dismantle oppressive systems in their everyday lives and workplaces."

END NOTES

1. USAFacts. “Unemployment and Income Have Long Differed by Race. Coronavirus Hasn't Helped.” USAFacts, USAFacts, 23 Sept. 2020, usafacts.org/articles/unemployment-race-coronavirus-income-great-recession-job-loss-2020/.

2. “G1375 · Index: Youth & Families, Families.” Cultural Competence: An Important Skill Set for the 21st Century, extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/html/g1375/build/g1375.htm.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Carter, Jameson A, et al. Edited by Gene Falk, Congressional Research Service, 2020, Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic: In Brief, fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R46554.pdf.

2. Everett, Gwen. “In Reckoning over Race, Museums Confront Their Pandemic Layoffs.” Crain's New York Business, 9 June 2020, www.crainsnewyork.com/arts/reckoning-over-race-museums-confront-their-pa...

3. Lena V. Groeger, July 20. “What Coronavirus Job Losses Reveal About Racism in America.” ProPublica, 20 July 2020, projects.propublica.org/coronavirus-unemployment/.

4. Mackey, Katherine, et al. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19–Related Infections, Hospitalizations, and Deaths.” Annals of Internal Medicine, www.acpjournals.org/doi/full/10.7326/M20-6306.