The idea that art produced in response to fashion trends is somehow unworthy of respect doesn’t hold water for me. Art history, broadly viewed, is a history of fashion, and vice versa. The two are not mutually exclusive, as they borrow from each other all the time. An obvious example is Yves Saint Laurent’s “Mondrian” dress of the ’60s.

Susan Tunick, scholar, artist, historian, and president of Friends of Terra Cotta, a preservation organization devoted to protecting historic and architectural ceramics, discussed the immense popularity of terracotta as a material throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Used for both structure and decorative facades, terracotta’s prevalence in our cities buildings today is striking, but its durability is not surprising to those of us who work in the medium. She urged everyone to “look up” (instead of down at the little tiny screen in your hand?) next time they are walking around New York City, Chicago, or Boston, to take note of the beautiful terra-cotta ornament. In New York, the French Building on 5th Avenue and the Chanin Building on 42nd Street sport impressively large, intricate, and well preserved terra-cotta facades.

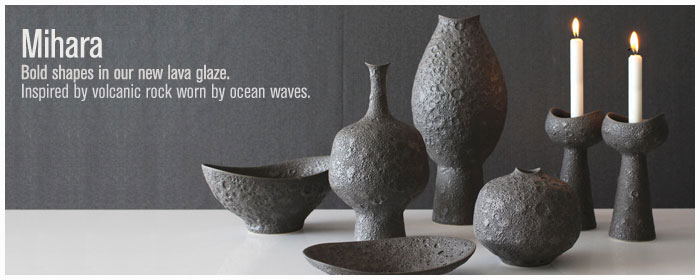

David Klein and James Reid said that when they began their Brooklyn-based ceramic design company, KleinReid, in 1993, potters weren’t using industrial techniques in their processes. David and James weren’t interested in fingerprints, or “evidence of the hand.” A clean, “factory” aesthetic was exactly what they were after, but to this day they’ve remained a studio, not a factory, and still design forms, develop glazes, and produce wares in-house, by hand. They were pioneers in the field; have you noticed the recent trend for clean lines, monochromatic glazing, and crisp decals in studio pottery? This duo also admits that they love the “fashion” aspect of what they do – it pushes them to develop and release new lines of products every year, sometimes twice per year. Still, though, they say the “customer comes last” when it comes to the inspiration for their work, which could be anything from a flea-market vase to a volcano in Japan.

Broadening the discussion of fashion even further, Glen Adamson’s presentation got me thinking about fashion as it relates to social habits rather than tangible objects. I remember my father telling stories about his grandparents’ farm in Indiana, and how on Sundays they would go “calling.” This didn’t involve a telephone or even a car, but rather, the horse and buggy, hats and gloves, and knocking on neighbors’ doors. Now, the most prevalent way of communicating with your friends is through a tiny screen, the “cloud”, and emoji. We communicate in Helvetica rather than hear, speak, or write. The text message tells us nothing about the mood or identity of the person who wrote to us, as a handwritten letter would.

What I’m getting to here is some thoughts on Adamson’s term “material intelligence.” Adamson, art historian, writer, and former Director of Manhattan’s Museum of Arts and Design, asked if anyone knew anything about the chairs we were sitting in; if we could name any of the materials they are made from, or explain how they were constructed. Of course the answer was a flat “nope” for some, and for the craftspeople in the room, we were all thinking, “Well, let’s see, this part is some sort of polypropylene, and this part has some screws here . . .” NO! The answer was no. Nobody knew. We stopped trying.

We, who embrace technology (the majority of people in the developed world), are becoming less knowledgeable about most of the “stuff” in our lives, and this stuff holds less information – historical, material, and cultural signifiers that we can use to understand it. We are more invested in the virtual world that is flat when in view, and disappears altogether when we put away our devices. Thus with good reason, we yearn for more tactile, exploratory experiences like the one that ceramics provides – either physically or visually. Is this why the current fashion of ceramics in New York is work by Sterling Ruby, Ken Price, and Arlene Shechet? Is this why everywhere you look, you’ll find artwork that oozes, slumps, and clumps (beautifully and seductively, I might add)? Even KleinReid’s newest line of pots is covered in bubbling lava glazes.

Adamson said that he is using the term “material intelligence” to create a commonality across a continuum of different sectors of art such as design and craft, which, in my view, have long and annoying history of bickering about inclusion (or exclusion). I speculate that an ability to share in our material knowledge across these [arguably false] categorical boundaries, or do away with them altogether, will positively impact what we are able to accomplish as artists, as viewers, as collectors. At the very least, let’s celebrate that more artists are realizing the viscous and visceral qualities of clay, and enjoy the bull market while it lasts.

The jury is still out on defining a New York aesthetic, but “Clay at the Core” gave its attendees a lot to think about. Here are some of my favorite quotes:

“I wanted to make it artificial in order to be palatable.” – Toby Buonagurio

“James came into the studio one day and said, ‘I’m going to cover those in flowers!’” – David Klein

“Craft collectors are not reproducing themselves as a species.” – Glenn Adamson