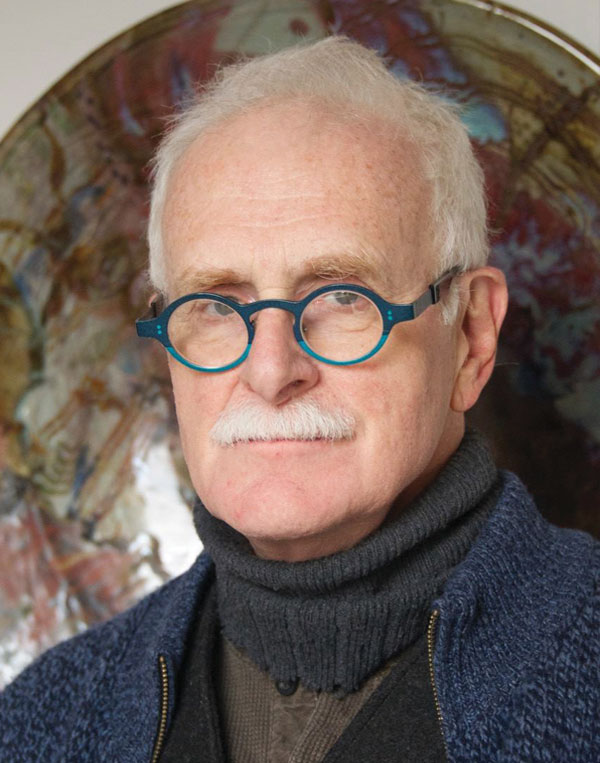

In Memoriam

By Jay Dion

Editor’s note: The following is an edited version of Jay Dion’s eulogy presented at a celebration of John Glick’s life near his new home in the California Bay Area on May 13, 2017. Please read his Studio Potter articles, and consider a donation to the Penland scholarship in his name.

In 2007 I was an artist in residence at Plum Tree Pottery in Farmington Hills, Michigan. I was one of thirty-three such residents that John Glick hosted over his long career, and I’m here today to provide a little insight to this extraordinarily generous, wonderful man.

John was the best! And in the field of ceramics, he was a giant. He was original and prolific and devoted his life to his craft. His work pays tribute to the honest pursuit of craftsmanship at the highest level, and it was his commitment early in his career to share his workspace with younger potters that made him truly unique. His intent was to share his knowledge, skills, and life experience and he understood that those of us who had studied ceramics in college would benefit greatly from the experience of working alongside an established potter, outside the academic environment.

When I contacted John to inquire about working at Plum Tree, I was living in Japan, finishing up a ceramics residency, trying to figure out my next move. This set off a series of e-mails between John and me in which he asked me to describe my work, my experience in Japan, and my goals for the future. They read like a therapy session, with John poking my stream of consciousness with little gems of insight. From John in one of his first e-mails:

So, the best I can tell you is to let me into your thinking—goals and personal reasoning and sort of where your head is on your present experiences in Japan, and what it means to you in present time (later it will mean more and different things as you move along).

He knew. He knew that my experiences as a young potter in Japan would be different from my later ones. He knew it would shape me in ways that I couldn’t possibly understand at that moment. He knew because he had witnessed the growth of each of his assistants both in the time they spent in his studio and out of it through the years. John wrote:

If you ask me what I feel are the critical areas of learning, I would say that they are huge and interconnected. At the root of "huge," I would identify several on which all the rest are built:

#1 Caring about the things you make; be attentive to your heart in the work. So much else follows on this key foundation block.

#2 Learning to work "smart." This is native intelligence, being willing to un-learn questionable habits and to become efficient and productive while keeping an eye, ear, and soul attentive to item #1. [...]

What followed our correspondence was my year at Plum Tree. I watched John throw massive platters with heat guns suspended above the wheel to keep them from flopping over. I watched him make mugs, little cups, teapots, bowls, jars—you name it. I watched him decorate and glaze his pots. We loaded kilns, made clay, cleaned floors. We ate lunch, we drank hot chocolate, we shoveled snow. I helped him pack up a van and drive down to Indiana for a weekend workshop. I witnessed him accept a large dinnerware commission from a woman whose parents used John’s dinnerware growing up and now wanted her own. I listened to him sing. I watched him throw logs into the cast-iron stove. I watched his eyes light up when Susie would come home from work. Opening a kiln, he’d get so excited and point out little moments happening in the glazes of finished pots. I read somewhere he made 300,000 pots. Despite this, he’d jump up and down—quite literally—at the sight of a particularly lovely interaction of glazes.

Watching John glaze a series of large platters was something I will never forget. It was a dance. His glazes were kept in medium-size Rubbermaid garbage cans, arranged on platforms around three walls of a small room in his studio. He would sway between the glazes working on four or five platters at once. Splashing, dipping, splattering, moving between each platter, reacting intuitively to the layering of glazes. Using wax resists, fan brushes, pouring from a ladle—so many different techniques came together to bring his work to life. I would watch him in silent awe. I know he knew I was there, but my presence didn’t appear to register with him. This dance was pure and honest, and it was possible because of the forty-some years he had dedicated to being a true potter. And he was opening this world up to me. He was showing me that this is was it means to be free, to know in your heart what your hands can do. This was the true education that John gave to his residents. He wasn’t teaching me how to glaze, he was teaching me how to be myself, to work hard and follow my path, to be true to myself in my craft.

John was as dedicated to teaching as he was to ceramics. He cared for each of us and respected us as peers. So John, from the bottom of my heart, I want to thank you. You gave us time with your amazing life force, and it will never leave any of us.

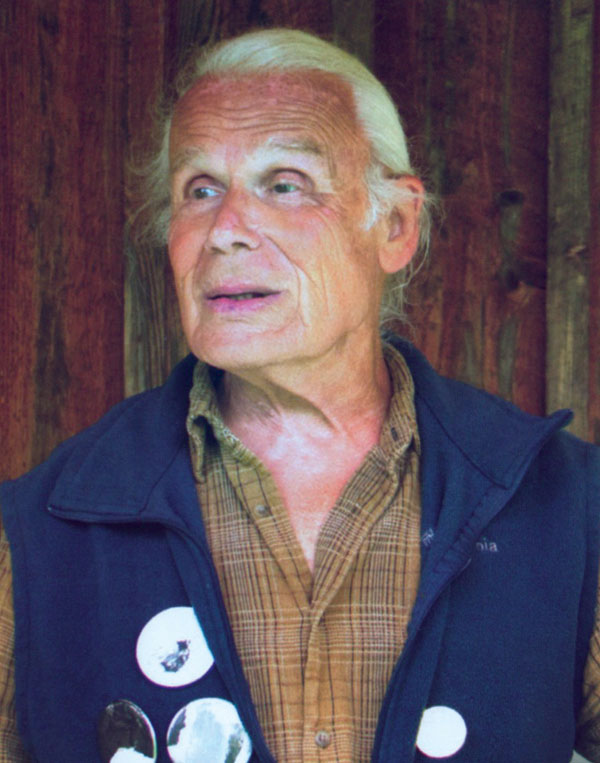

Robin Hopper, 1939-2017

By Cathi Jefferson

After attending art school in London, Robin and his first wife, Sue Hara, immigrated to Ontario in 1968, where he taught in Toronto and Barrie. In 1977, he moved to Metchosin, about twenty minutes outside of Victoria, British Columbia, transforming two-and-a -half acres into what he liked to call his “Anglojapanadian garden.” In Metchosin he raised three children; there he established Chosin Pottery, where he worked as a full-time studio potter.

Robin taught workshops all over the world and wrote extensively, including eight books on ceramics and articles on other interests, such as gardening. The Ceramic Spectrum and Functional Pottery broke new ground, as did his series of “how-to” videos. I remember a friend telling me that when she started to make pots, she lived in a small town with no access to hands-on instruction and learned to do it from Robin’s videos.

In 1984 Robin and his second wife, Judi Dyelle, got a group of potters together and began Fired Up!, an annual show and sale that thirty-three years later is going strong. That same year Robin and a couple of artist-friends started the Metchosin International Summer School for the Arts (MISSA) at the Lester B. Pearson International School in Metchosin. For twenty-five years Robin taught the MISSA glaze-calculation course. Robin would work with students ahead of time, putting together a glaze program for each. Viewing and discussing hundreds and hundreds of test tiles at the end of the class was an amazing experience.

During the last two years of his life, Robin battled liver cancer. He spent time with his children, and friends came to visit from all over the world. They helped him create his Swansong DVD documenting his remarkable life. Robin’s Celebration of Life ended with Monty Python’s “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life,” complete with images just like the show’s—you remember the zany graphics! As balls, heads, and more bounced over the lyrics and we all sang along, I’d like to think Robin was singing along, too. Robin wrote in his book Robin Hopper Ceramics—A Lifetime of Works, Ideas and Teachings, “I dreamt my life, and then I lived my dream.” He certainly did.

Please read Hopper's Studio Potter articles here.

Paulus Berensohn, 1933-2017

By Skip Sensbach

news.

For me, hearing the news that someone has died always elicits reflection, and his passing was no different. I started thinking about “way with clay.” As was true for a whole generation of potters, I was introduced to Paulus through Finding One’s Way With Clay. This book captured what I thought working in clay should be like: a meditative and creative journey. And one that is spontaneous, life-giving, and always open to possibilities.

I was not very close to Paulus personally, but his philosophy on life and clay has guided my life in clay. I was very fortunate to have met him when I was working on my essay for a catalog, The Endless Mountains Spirit, that accompanied the 2015 exhibition of work by him and M.C. Richards at Marywood University, in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The highlight of that project was my visit to his residence near Penland School of Crafts. Sitting with him for an afternoon was an experience I will never forget. Very few people embody the creative spirit; Paulus was one of those rare people living completely in the creative moment.

When I begin teaching a new class, I always start off by introducing my students to Paulus’s work and his way with clay. I was recently hired to teach ceramics at Severn School in Maryland. When I went for my interview, I taught a sample lesson with the students that included the section of Paulus's book called “An Approach to Work.” In that section, Paulus talked about creating a begging bowl for all his daily needs. I had them read it, and we pinched pots together, while I told them about what an amazing person and artistic influence Paulus was to so many artists. I will continue to celebrate his life, as I think he would want, by pinching pots and talking about the creative process that is within all of us.

Please read Berensohn's Studio Potter articles here.