An Interview with Norm Schulman

Stan: Let's start with a basic biography.

Norman: I was born in New York City, October 27, 1924. My father was a craftsman, an upholsterer with dreams of being a gentleman farmer. My mother was a seamstress, very talented. I have no brothers or sisters. Eventually we moved to a small farm outside Spring Valley, NY. My education was the normal grade school, high school. I had some advantages in that at our school music was very important. I got involved with that, first playing violin, then trombone and euphonium. I thought maybe I'd like to be a musician. Out of high school, I went to New York and studied trombone for a while and worked as an usher at the Paramount Theatre until I was eighteen - a little over a year - and then the United States Army got me to participate in World War IL I did that for three years, from March 1943 to March 1946. Served eighteen months overseas in the European theatre. I wasn't too distinguished a soldier, so I came out of this an Ammunitions Corporal, Field Artillery. When I came out I didn't know what to do with myself. I wanted to be a musician, so I played in a dance band. We had a steady weekend date at a road house/dance hall type of thing. And I continued to play in the local symphony orchestra. I started taking lessons with a very influential trombone player. I moved to New York, lived in one room. Took lessons once a week, practiced six hours every day, and didn't improve much. So I got the idea that my talents weren't there and I'd just have to go learn something else if I was going to make a living.

In the meantime I had met Gloria, my wife of fifty-seven years now, so I guess that stuck pretty good. I took some aptitude tests the Veterans Administration gave, and I ended up going to Parsons School of Design to study interior architecture and design. I did that for three years, and along the way started going to New York University night school for my academics. By chance, I got into a painting class and did very well in that, and by further chance, my last semester I found myself in a ceramics class. The mud really attracted me, and the wheel business, and that was the beginning. At New York University, the ceramics class was in the Industrial Arts department. My teacher was Ruth Canfield, and she was a marvelous teacher. She had graduated from Alfred in about 1919, had been one of Binns' assistants. So in the Alfred history I'm part of that chain, and so are you. (Both quietly laugh.) I finished the three-year-diploma course at Parsons in 1950, and I had another year to go to get a degree from NYU. The only saleable training I had was in interior architecture and design. I tried, but I just didn't fit. Couldn't find anybody I wanted to work for. Couldn't find a place to work. I had one really good design job and then it was Gloria who was paying the bills. I had a friend who was a poet and he was working for Curtiss-Wright [an aeronautics manufacturing company] as a technical writer. So I went down and applied for a job.

I was interviewed by the personnel director: was I able to learn new tasks? I was hired to do materials handling design and it turned out that part of the materials-handling group was also package engineering. I guess they liked the way I did things, and so two years before I left them I became supervisor of the group. I learned that I really did not like the industry business! All this time I had been making pots. My in-laws had a garage they let me use for my pot shop. It was my hobby and I was enjoying myself. There weren't a lot of potters around. A really great one lived in the same county, Rockland County – Henry Varnum Poor. He was a painter and a potter, wrote a book on pottery. He had done a workshop down at NYU and I had met him there. It was an inspiration to me to see this fellow. He'd built himself a wood kiln from what he could find. Taught himself how to make a clay body, dug his own clay. He was a famous portrait painter and started the Skowhegan School of Art up in Maine, which was a very well-known summer art school. He was a remarkable man. Luckily for us there are always these kinds of people around. There has to be somebody around to inspire you.

Our daughter Laura was born in 1953. One night in 1955 I came home and I'd just really had it with the politics. So I asked Gloria how she'd like to be a potter's wife instead of a packaging engineer's wife. She said, "If that's what it takes to make you happy, go for it." I think that's a famous statement, myself. I went to my teacher, Miss Canfield, and spoke to her about wanting to go further. She suggested I go to Alfred and said she'd write a letter for me. She wrote the letter, then got in touch with me and said, "You go up and see Mr. Harder, he's the head of the art programs at Alfred." So I wrote and told him I was coming and what date I was going to be there. I didn't wait for any answers, I just packed up Laura and Gloria and took a ride up to Alfred. He was very nice, very gracious. He never asked me once for pictures or slides of my work. Just spoke to me about who I was, what my experiences were. And we got around to talking about coming to Alfred to study. He said, "How much money are you making there?" I told him, and he sort of sat back in his chair and looked at me for a while and he said, "You know, young man, you are making $2000 more a year than I am. Do me one favor. I have the feeling that you're just fed up with your job. Go back, give it a year, and if you still feel the same way, there's a place for you." Well, I thought that was reasonable. The man was being very humane about it, didn't just chuck me out. So I went back. And I worked about eight months, then wrote him a letter. I said, "I took your advice. I'm throwing myself into this, doing the best job I can, but being a potter is what I want to do." And I didn't even ask him. I said, "I'll be there at the beginning of classes, late August." I never got an answer no, so I was there. This was 1956. I went to Alfred from 1956 through 1958, got my MFA in 1958.

S: I remember you told me once that when you graduated there was only one teaching position available.

N: Actually there were more, but they weren't on the market yet. There was only this one at the Toledo Museum School of Art and another opening at Archie Bray. My competition then was Ferguson and Henry Lin. Ferguson went to Archie Bray and Toledo chose me over Henry. Henry later went to Ohio University and eventually became dean of the art school. His daughter, Maya Lin, designed the Vietnam War Memorial. The Toledo Museum was a beautiful, classic museum. The architecture was classical - Corinthian columns and all, beautiful broad marble staircase. Toledo was the glass city of the United States at the time. That's where the money came from.

S: Oh! I had wondered how that glass workshop with you and Harvey Littleton came to be in Toledo.

N: Harvey had taught there in the early 1950s when he was going to grad school at Cranbrook. Taught there three nights a week, and literally started the clay program at the Toledo Museum School. Then a woman named Naomi Powell took over the clay from him, and I succeeded her. My work week was Tuesday through Saturday. Tuesday and Thursday I did three 2-hour classes, one in the morning, one in the afternoon, one at night. Wednesday I did two 3-hour classes, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. Most of these were beginners, some intermediate students. The Thursday morning group was a little different. They were advanced students and stayed all day, so those students who carried over from Tuesday moved in and around them. These Thursday people had been coming there for years. So, my first Thursday- eight o'clock, nobody there; eight-thirty, nobody there. I thought, "All right. Word's out they've got a new teacher and they don't like me because I raised the dickens in the other classes."

At nine o'clock a lady comes in with a tablecloth and linens and a casserole. Then somebody else comes in with a casserole. I was just standing there watching, you know. Then pretty soon somebody came in and turned on the electric kiln, didn't bother bricking it up or anything, and then the ladies with their casseroles filled up the kiln and heated up their casseroles, spread the tablecloth, and were ready to have lunch. I just stood there, and then walked over and introduced myself. 'Tm the new teacher." "Oh, how charming!" they said. They were really very nice. But that was their social thing of the week. I was fresh out of graduate school, you know, and I wasn't very sympathetic to that. I told them to clear the tables. Lunchtime would be from twelve to one. "You can do as much cooking and eating as you want from twelve to one, but my class ends at twelve and another begins at one and I need all the table space and all the kiln space for my classes." Well, I started out the week with 150-some registered, and I ended the week with ninety. Fridays, no classes. But no assistants to make clay, no assistants to fill the glaze materials, so I did all that. As time went on I also prepared the glazes and the clay body. They had a big barrel and they dumped the stuff in, added water, mixed up this slurry. There were a whole bunch of bats made with pie tins, and the students would take a ladle, put some thick slurry on one bat and put another on top, and they'd do that with a stack of bats as high as it would go. I didn't like that so I made my clay body. As for my own work, I didn't like working down in the studio so I had a studio out back at my house. And I built my first kiln. I made pots on Sundays and Mondays. On Saturdays I had three one-and-a-half-hour classes with kids ranging in age from nine to twelve. My smallest class was forty-eight, my largest was seventy.

S: That's incredible! What did you get yourself into?

N: (Laughing) Well, I needed a job. I had a family, I needed a job. And I had access to the vault. I could go in the vault and handle these things that were 1700 BC, 1800 BC, on up to today. I had two large showcases, and I'd use one for historic pots and another for the best ones coming out of each kiln. When I left, the person who took my place was Jack Earl. There was a series of good people coming through there. The museum had a great gallery with spectacular paintings. The reward there wasn't in the money, I'll tell you that right now. The Museum School was hard on me, it really was. I wanted to leave every minute I was there. But in retrospect I'm grateful to have had the opportunity, and for what I learned about the human experience. I never learned how to be a kind teacher, though. I was always pressuring the students to do better, reach further, you know. In a way, when I was doing that I was addressing myself. When I was telling students to search a little more, look for what's not so obvious, I was actually telling myself that.

S: You did them a great service by pushing. And I also understand when you say you were addressing yourself. It's awfully hard to keep that kind of momentum, to continue to push yourself, particularly when you work alone.

S: After Toledo you moved to Rhode Island?

N: Well, Toledo made it very easy to leave. They didn't pay and expected a lot out of me. If you wanted to go to a conference, they wouldn't help you out with fifty cents. They didn't like you leaving even for a day. They didn't want to pay anything and they didn't want to lose you, either. There was a teacher at RISD, Robert Archambeau. I had been his mentor while he was a student at Bowling Green State University, so when he came to Rhode Island he recommended me. By then I had been involved in glass, and knew as much about glass as anybody at that time, maybe, except Nick Labino and Harvey [Littleton]. And I liked the idea of glass, though I wasn't crazy about working with it. I thought the material was gorgeous, I still think so. I mentioned to them that I'd been involved in glass. The head of the fine arts department was Gil Franklin, and he had a sort of alter ego, a painter by the name of Gordon Peers. Peers let me know that he didn't care a whit about clay- clay would never go anywhere or do anything - but he'd love to see glass. I used the glass, literally, to save the clay program. I got a good budget and I set up a good program for clay.

When I arrived at Rhode Island there was no place for glass at the school. Archambeau had gotten a place for my family to live in a town called Rehoboth, just over the border in Massachusetts. We lived in a house built in 1876 and built a studio there. I had taught a graduate glass class at the University of Wisconsin that summer, and I had gotten paid $1800 for it. For $ 1800 I built a building that had a cement pad and on part of the pad I built what was the first RISD glass studio. I literally welded up the frame for it. We did that between August 15th and Christmas time. Right after Christmas was the first glass class. I taught the students how to build gaffers' benches and how to do electric welding. We built hand tools. We built two furnaces to melt glass in and two annealing kilns. We did all that in two weeks of steady work, and at the same time I was teaching my second semester of clay classes. I didn't know whether I was going to get that interested in glass myself. We were in that building for three years. I came fall 1965, and January 1966 we started the glass program. The third year Dale Chihuly came as a grad student. So that's how we got the program started at Rhode Island School of Design. There are people at RISD who don't know that.

S: How did you juggle this and the ceramics program? You must have worked about eighty hours a week.

N: Yeah, that's what I worked. I did that for three years. I tried glass. I worked hard at it. I made pieces that got into shows, the earliest contemporary glass shows at the Toledo Museum and other places, and I think they'd flunk me out of the class if I submitted that now! (He laughs heartily) But I learned I don't like the process. It's too hot for me, and I want to get my hands on the material. You can't get your hands on hot glass. I'd get as close as you could by shaping with wet newspapers in my hand, but... S: Yes, you don't have that intimacy with glass that you do with clay. N: That's true. But it's quicker! You come to a conclusion faster, and that's another thing I'm not enamored with. I like the idea of working out what a form is, pushing it to the limits that I feel are there. That's pretty important to me.

Penland

S: While you were at Rhode Island you went on a sabbatical, didn't you? Was that your first encounter with Penland School?

N: My first encounter was in the spring of 1971 when Bill Brown asked me to come down to discuss the residency possibilities. Penland had an NEH grant for teachers who were either on leave or on sabbatical. I came down the last couple days of March. It snowed, and I rented a car at the airport, got a map, and the most direct route on the map was the Parkway.

S: (Laughs)

N: Why does everybody laugh when I tell that? Anyway, I made it. I drove in and Fritz Dreisbach was here then. Fritz was the glass resident and we knew each other quite well. He had an extra bed so I stayed with him. Toshiko Takaezu was here then, too. The next day Bill Brown cornered me and said, "Listen, there's a bunch of glass people here now and they're having their very first meeting and I want you to talk to them." I said, "Bill, I'm not an expert in glass. You've got to get Harvey or Nick or somebody like that." He said, "Doesn't matter, you're talking to them." So I addressed the very first meeting of GAS. That's what it was. There were maybe a double handful of people there. All I did was tell them anecdotes, and what went on at the first two glass workshops in Toledo with Harvey, that sort of thing. At that meeting Bill told me I could have the grant. Turned out it was the last one available. So I came down in the fall of 1971. It was a six month residency: materials, studio space, food. They were doubly kind with me because they gave Gloria the same thing. She had use of the darkroom, and we had a stipend.

S: So the time was pretty productive?

N: Oh, you know, walking into a situation cold, working a lot of stuff out of your mind, stuff that's been cluttering it up. I didn't have a show of the Penland work. I made the

stuff and sold it. I needed money- I was on sabbatical, going to Mexico [in the spring]. And my daughter had come home after a year on the road and decided she wanted to go to school. I was on half-salary, and I needed to pay for her school, you know. So I made bowls and lidded jars and tea pots and things like that, and sold them.

S: Did Mexico influence you to start using more color?

N: I don't know. It may have had an effect, but mostly I was just tired of seeing all this gray and black in my stoneware and porcelain. I had started doing color with porcelain where I had either black or red as the base color of the piece and an area, sometimes a stripe right around the middle, with colors of yellow and blue and red, things like that. I went from that into saltglazed porcelain as a result of a three-week workshop I did at the University of Illinois in Bloomington. Torn Malone was teaching there, and Tim Mather. One of Tom's S!udents had built a salt kiln, a special little catenary-arch kiln. I asked Torn, "Can I fire that thing?" I just happened to have my hands on some porcelain and I made enough pots to fill that little kiln. I did a lot of brushwork with rutile and over-sprayed with cobalt chloride. Well, I fired it and I didn't use a lot of salt, and it came out with that orange-peel texture, and a great effect where the chloride was over the rutile and salt. I was very much inspired by the results of that salt kiln. I got color effects that I'd never seen before, very much like the art glass of the Art Nouveau period, and you just don't see that on clay. It was exciting and inspiring, and I worked with that. We had a salt kiln at RISD and I started doing salt-glazed porcelain.

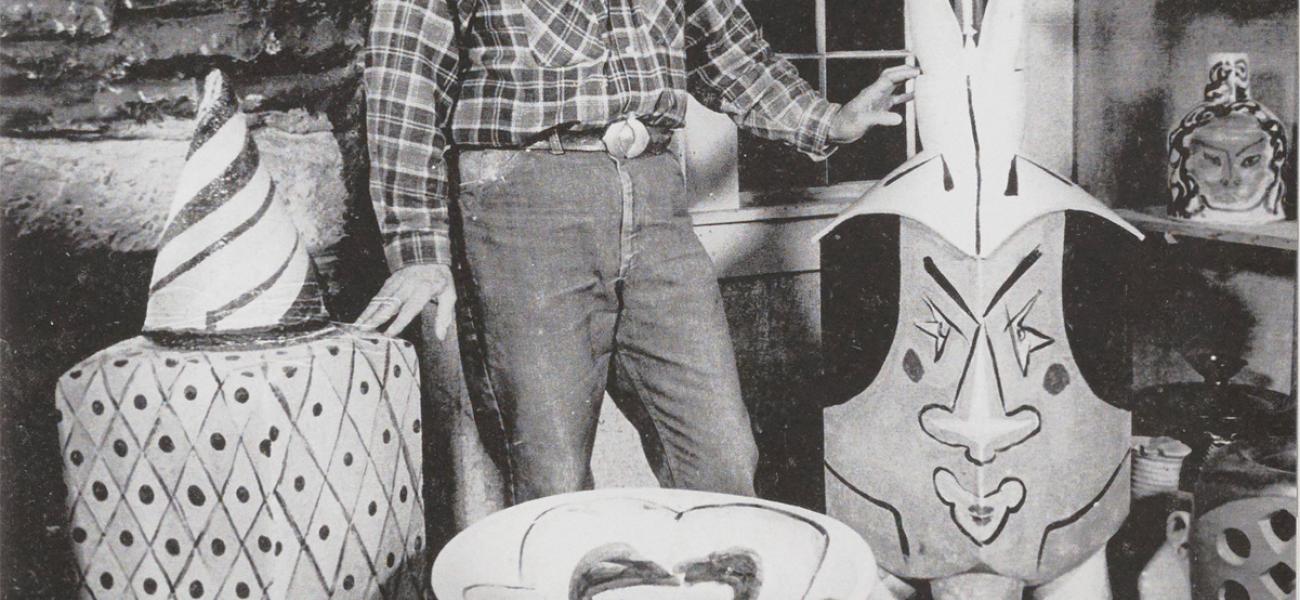

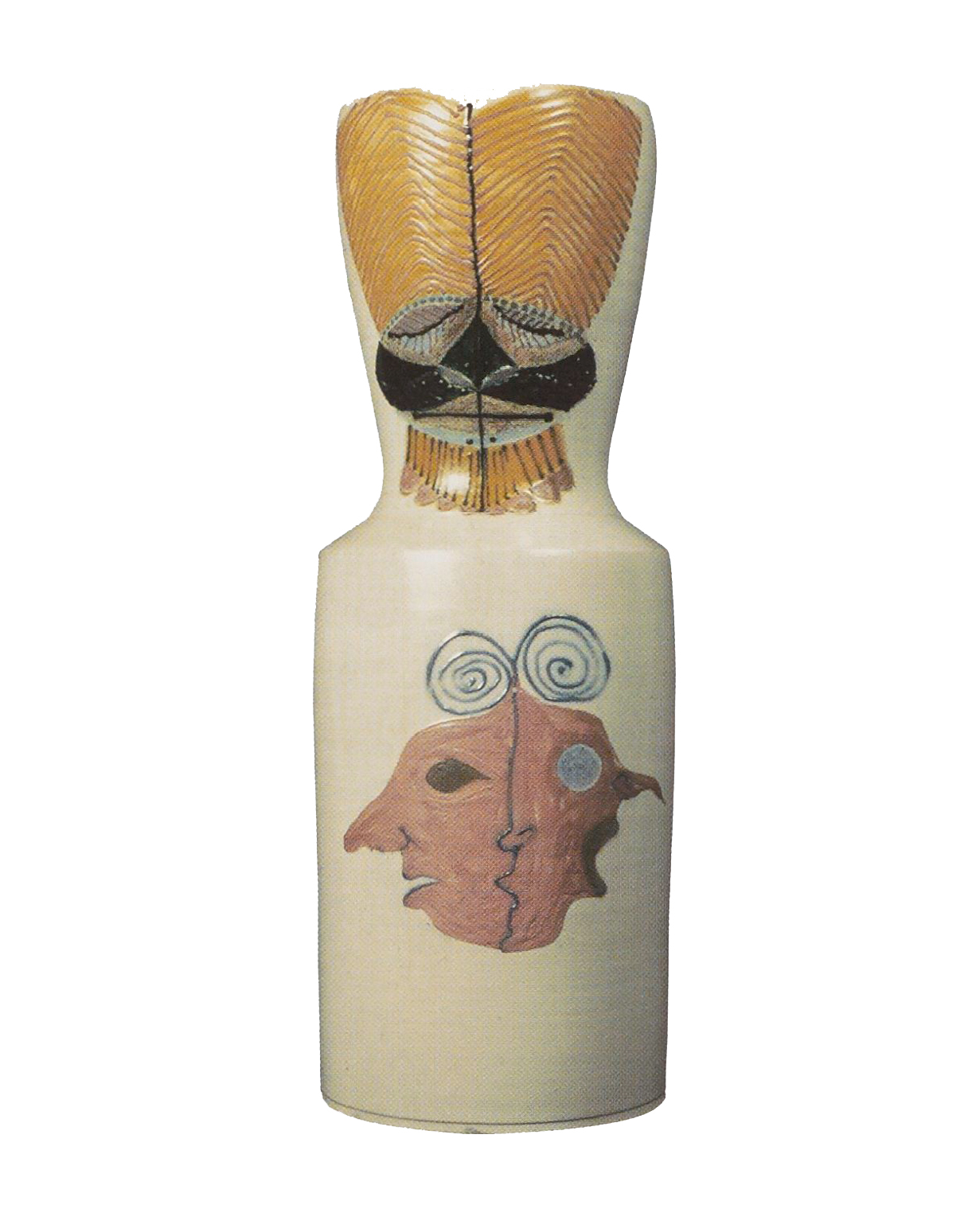

At RISD my salt glaze was a little more intellectual, a little more planned, than what came later. I was working out what kinds of forms were more suited to what I was being inspired by. I worked with the salt for more than twenty years. But I didn't do that exclusively. I never wanted to stick with one thing; I liked to have one thing as my main effort, and then something else going on which was investigative - that would lead to something deeper, more meaningful. So when I moved down to North Carolina I set up a kind of work schedule that would accommodate that thinking. From December through March I worked on larger, more sculptural things, and from April through November I worked on salt-glazed porcelain, just a few very simple shapes. Tall step cylinders, a rather good-sized platter form that I called a charger. Very similar in nature to those medieval English chargers, except this had a broader flange, because I wanted that flange to paint on, and a shallower center, because I wanted to paint on that, and I wanted them to be different but interrelated. It was a challenge - a challenge in design, a challenge in color organization, a challenge in form. The cone three work that I did was sculptural; I wanted to tie together sculptural forms and painting. The forms were sort of humorous, so almost without thinking I started doing harlequins. I did them for years because there were endless shapes that I could use in my painting, and the forms were sort of like large toys. And philosophically, the harlequin and jester represented the people's way of telling the ruling classes the things that were making them unhappy, and what they would like to see improved, and it was done in such a way that reprisals would not be forthcoming. The working classes could tell the ruling classes what they thought of them. I like that. I was able to get some of that into the work, too. And I had seen some acrobats - I don't remember where, maybe a circus - so I started doing these paintings of acrobats. I made a rather good-sized bowl, about two feet in diameter, on tripod legs, and it seemed a great shape for acrobats twisting their bodies in all different ways. The body shapes themselves were beautiful to work with. And as I did more and more of these paintings I began to see that it wasn't the sculpture that I really wanted to do, it was the painting. So I stopped making these rather round, full-blown vessel shapes and I just started working on a vertical slab, the stele.

I got into it seriously in 1983-84. I was invited out to be head of ceramics at Ohio State and I was teaching there for those two school years. I had a small studio, but it was adequate and it was on one floor, and I could roll my work to the kiln. At that time I hadn't built the studio we're sitting in now. My studio was the old house, with slanted floors and different levels, and making large pieces was tricky. I worked on the steles for the rest of the 1980s and pretty much of the 1990s.

S: I'm interested in how you organized your time as a studio artist.

N: I didn't organize my time! (Laughs) I just immersed myself in my work. My attitude is best expressed by the title I used for a couple of one-man shows. It was "Daydreams and Fantasies," and truthfully that's what my work was all about at the time. I'd make a shape, and that was my canvas, and it might sit around for heaven knows how long before I'd just walk over and start working on it, drawing and painting on it. I gave myself absolute freedom. I don't know whether it was good or bad, but that's what I did, and what came out of it were my daydreams and my fantasies. Was I influenced? I must have been, because everybody has daydreams and fantasies, and you see it in the work. Could be from anthropology, archeology, art books about painters I really like. It came from everyday life; it came from what's around me. It might have been the way my dog was lying on the floor, the shape he presented, or it might have been the cat cleaning himself. My wife was often my subject, or a leaf from a tree, or a fish. Before I started a body of work I'd take a good-sized pad of newsprint and start drawing, inventing all the time through that. And then when I just couldn't stand to work on newsprint anymore, I'd go to work on the clay. I don't follow my drawings; if I leave them around I start copying them, and to me the work doesn't have any life. So I wad them up and throw them in the trash and get to work in clay. I threw the newsprint away – I didn't want to be influenced by it. Probably not too smart a thing, people want to know what your thoughts. come from. The drawing gets my system working, gets me into the spirit of making. It stimulates my imagination and intuition. I prefer not to intellectualize if I can help it. Sometimes when I've had commissions to do, well, then it's important to have an iconography and have it be meaningful to the commissioners. It's important to work within the framework. When I did a commission I didn't feel I had the right, unless it was conferred upon me, to do anything I pleased. I felt that if someone was coming to me and offering me a commission that had specific requirements, it was up to me to not only fulfill the requirements, but to fulfill them so that it would be understood and recognized. I don't know if I did or I didn't, but I tried.

North Carolina

S: I take it your experience as a resident at Penland must have been pretty reinforcing, since it wasn't long after that that you decided to buy property and have a house and studio here?

N: Well, I had decided that I was finished with teaching. I found myself becoming angry at times with the students. They were changing, their attitudes were changing, and I didn't feel I was responding well to that, so I decided I was going to stop teaching. I was leaning toward Oregon because one of my best friends, a colleague who had shared my studio for a number of years, had moved out there. He had a place right on the coast, on the side of a mountain, and it was really beautiful, so I was kind of headed in that direction. But when we were here in Penland, Gloria was out doing photography and meeting people, riding around and looking at the landscape, and she kind of fell in love with the place. Later Ron Probst, who had a pottery here, called me up and told me about this place that was for sale, and said if I didn't want it he'd buy it. So I flew down, looked it over, and bought it. This was 1973. And it was, you know, this old house! We had to figure out what to do.

First thing, we built a kiln. Then we came up for a couple of summers and I rented space from Ron Probst. It looked like a good place to stay, so when the opportunity came we bought another acre of land with the idea we'd build a house on it. I enjoyed working here. And the proximity to the school. I liked the way the school was being run at the time. Not the most efficient way to run a school, but it had a spirit to it that was quite lively and rich. I just enjoyed that. And Gloria was enjoying herself here. There were a couple of great blackberry patches that we investigated and plundered. There was a spot where we could have a vegetable garden. Just a lot of good things in life going on here, and interesting people. Everybody was worried about us. When you're used to teaching, and getting a salary and perks -well, it wasn't going to be too easy for us. It wasn't, but we've enjoyed it

very much.

S: Gloria has certainly made a place for herself in the community.

N: That's right. Well, she's a very caring person. She's a people person all the way. She was a very good stenographer, and she took jobs like that to begin with. She had a couple of credits towards college in Rhode Island, and she started working on her college degree, went to school nights, took extension courses from Mars Hill. Later when we went to Ohio State she had two more years to fulfill, and she got her degree and became a geriatric social worker. There was no one around here like that. She worked at the hospital in Burnsville [NC], then at a nursing home in Mars Hill, and when they opened up a nursing home here in Spruce Pine she worked there. She started hospice, got it going. She's done all those things that had to do with public service. A lot of it working for half-pay or less, and volunteering. Now she's director of Mitchell County United Way, and I don't think she's getting close to half-pay. But that doesn't matter to her, because it needs to be done, it's a good thing. I'm proud of the people there because they recognize and appreciate her.

Work

S: You've talked about how you focus on problems or forms, and how you zero in on them. I remember you telling me once about your sculpture, "I had to make these. These aren't oriented toward a market; they're things I have to do."

N: Yeah. Just about everything I do is that way. I decided to do this way back. And literally risked our livelihood. I wasn't going to try to analyze the market. I wanted to preserve that sense of independence. That comes at a price, though. People don't appreciate it. Later on they might, maybe after I'm dead. If you're independent you're off on a tangent, but it's something you recognize and choose to live with. I've come to the conclusion that my best work comes from doing my personal investigation. At least what I think is my best work. Who's to know7 I've enjoyed working that way, though, setting my own challenges and working to meet them. The hardest part of it all is to recognize when you've not met them, and to admit it. There are times when I put my best into it and my best isn't good enough. Sometimes what I thought was my best wasn't really. That's something I can't explain.

S: When did you start making the double-walled pieces?

N: I started that in graduate school – no, earlier. I had seen an Islamic pitcher, about 13th-century Persian. The outer wall was reticulated, floral patterns, that sort of thing. Saw it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It just blew my mind, because it had to do with duality. It struck me that it was like people. What they show to the world, and what's really behind the mask. I'm still dealing with that.

S: You've certainly worked in a lot o f different techniques.

N: I think nineteen years straight of teaching contributed to that. You've got to have something to teach, so you've got to try things. It also sets an example. By trying different things and getting different effects, students see you don't have to work to get one style and stay with it all your life. My old teacher, Professor Harder, watched me working when I first came to Alfred, and he didn't pay a lot of attention to me, I thought, for about three-quarters of the year. Second semester I started developing a very definite style, and Harder took Gloria and. me out to dinner about twenty miles away, good restaurant. He took me for a little walk away from her and put his arm on my shoulder, leaned over like it was a big secret, and said, "Don't be in too much of a rush to develop a style. Let your style evolve on its own." I said, "What if it never evolves?" He said, "Well, at least you'll do some very interesting things." I said, "Don't you think a style can be interesting?" He said, "Yes, but then it's over with so fast. After that it's all rote." He realized that along the way there are going to be long periods where it is rote, so you shouldn't be in a rush, let it happen by itself. It took you quite a while to develop your style, didn't it?

S: Well, yeah. It seems like it's always evolving, but the plateaus are longer the older you get, so I don't see that much happening. And I get impatient with myself.

N: That was my problem.

S: It's a problem when you're making your living. It's difficult to move out too much, to go off in an entirely different direction.

N: Well, you've got a heavy commitment. A commitment to earthenware, to utilitarian, to the glaze you use, and you have all this equipment that's set up for what you do. You can't fly in the face of that. Frankly, during the twenty-two years I was doing those porcelains, I was in exactly that position. I was totally committed. As a matter of fact I was committed just before this move to wood firing. This move was economically very chancy for me right now. I'd really just about finished paying for that big kiln that was put up there to fire large tiles and steles.

S: That's something about you that I find rather remarkable: that you're willing to take the risks you need to take to do something different. But what're you going to do - wait till everything's paid off?

N: Hal I buttoned up the salt kiln; it still has a good ten years left in it. I tore down one small kiln and turned it into the car kiln. That car kiln has a lot of years left in it. But I don't have a lot of years left in me! I bought an electric kiln, and I'm not happy with it at all. Probably because I don't know how to use the control on the thing; it's got one of those fancy controls. I'd like to be able to override it at certain times, and I haven't found out yet how to do it.

S: Here's something we haven't talked about: your thoughts on color and scale in your work.

N: Scale is tricky, and it's very important. I say that because I recall a time in the r95os when a very well-known American potter made these shapes that were like what other potters made, only he made them four and five feet high, then made them ten to fifteen inches high. It seemed that the ones that were 10 to 15 inches were just right for the shape, and the ones that were four and five feet high were wonderful examples of throwing skill. But you know, we stand on a mountaintop and shout one thing and we stand on a molehill and shout another. I think color can be used to balance a form, to enhance and enrich it. It can be used for very subtle effects. But it can become a trap like anything else. It's just a tool; it's very significant, but it's just a tool. A piece of work should have a presence and it should own the space that it stands in. If it's color that helps you get there, or enhances what's there, that's fine, but if it's color just for the sake of putting color on, what's the purpose?

S: You brought up something about working in series, and I'd like to hear about that.

N: Yes, what keeps me cooking. When I've finished a body of work and I'm ready to go to work again, most of the time I don't really know what I'm going to be doing. Sometimes I've thought of something and I can't wait to get to it, but then sometimes I just haven't thought of anything. I walk into the shop, looking for what to do, and if I can't think of something right away I take a pad and start drawing. If I don't have a place to start, I just make a dot and take that dot for a walk - Paul Klee's wonderful description of drawing a line. And that creates lines and pretty soon you're creating planes and developing movement. I work like that until something starts jelling within me that I want to see. Images start coming. Usually the images are the result of me sitting there doing absolutely nothing. Maybe that's meditating. I don't know what meditating is, but maybe it is.

And I'm a dreamer. I've always been that way from childhood on. An only child, I lived on a farm, and we were far from things and people and town activities, so I had to create my own life. It came out of dreams, and I guess that became a habit. I'll sit there and pretty soon I'm dreaming of activity, of shapes, of colors. Sometimes I have adventures in my dreams and they inspire things to happen. For instance, the steles came out of dreams. The figures I have on them were in the dreams and I just pulled them out. My pitcher shapes came out of a combination of things. When I was at Alfred, Professor Harder just loved those medieval English pitchers and he was always talking about them and showing us examples. So I had to do it, and it stuck with me. I still do that sort of thing. One thing about working that way, there always seems to be a better way to say it. In searching for the better way I would make things in series. Just go through one after another, in the drawings and then later in the actual making. Along with that the question of process comes in. Are these going to be objects I make on a potter's wheel, maybe a bunch of shapes that I reassemble, or is it something I'm going to handbuild1 I did a whole series of slab and thrown pieces that were assembled into abstract figures. That gave me the opportunity to paint them in patterns.

So, finding the process - how am I going to make this? - is the next problem, and working in series helped me do this because I dealt with the concept again and again and again, looking at if from different points of

view. I carried that right through the pots that I made and the painted sculpture, and right through the steles. And another thing, I guess, is material. My material is sort of dictated in a way by temperature range. Cone three for most of those sculptural things. High temperature porcelain for the pots. And the firing, salt glaze, because I had become accustomed to color and I found it to be very inspirational. I could actually make the pots for the colors. The way in which I expressed the colors on the porcelain was different from the way I expressed them at cone three.

Museums provided a lot of inspiration to me, too. To go in and see the works of the people that went before me. How fascinating it was to deal with a topic, go into a museum, and find that some five or six thousand years ago somebody else had dealt with the same thing. And had come up with a better answer. To me it's a great mystery. Where did they find these beautiful forms? How did they ever manage to make these simple things that are so mysterious and evocative? And what is there in man that makes us go back to those things that were made in clay? Another inspiration was petroglyphs in the Southwest. And in Peru those huge, drawn figures. It seems I like anything that's mysterious. I love mystery and I love myth.

S: You said once you were drawn to Borges.

N: Yes, his stories are kind of fantasies as well, but they're much deeper philosophically. He was deeply concerned with life and death and chance and a sense of inevitability. There is one story of these two gladiators preparing themselves mentally for that moment. One fighter knowing he was going to die, the other knowing he was going to kill, both driven. He did it so simply, yet it was a very passionate experience, and a frightening one. He told it so calmly. No ornamentation, just the story of two men facing fate and looking to the outcome. All his stories have that kind of feeling to them. As a matter of fact, the inspiration for the stele series really came out of Borges.

Music

S: I know you and Gloria play in a local orchestra. Music is still important in your life?

N: I enjoy playing and listening to it, too. It keeps me company all day. I can't call it listening, but it creates an ambience for me. When I listen I don't work. It takes energy to listen; if you really want to hear it you stop and listen. But in the studio I have it all the time because I like the atmosphere. I think it feeds me, feeds me subliminally. I feel better about my work and about myself when I have music on in the studio. Work takes my attention, of course, but when the music's not on I sense that something's missing. When you're not making things you're thinking about what you should be doing, and sometimes if things are not going too well I find that's a good time to go play a little bit. I play the euphonium. Get away from what's disturbing me. And sometimes I just do it for the pleasure of it. I belong to a little orchestra, a classical chamber music group. I play with them regularly, one night a week. Take home the music and practice. Gloria used to play with them also, but the tendons at the base of her left thumb became all entangled and she can't play any more. It doesn't seem to bother her too much. She's got her computer, and her photography, and now she's doing digital photography and she's got a wrinkle on it that's developed very nicely.

I need things to interrupt my thought all the time. I have a tendency to think about things that are annoying, so I exercise and that gets my mind into good shape in the morning. Get up and exercise for an hour. It clears some of the cobwebs and gets the blood flowing.

Church Fire

S: I don't know if you feel like talking about the church being burned and the loss of your collection. [Norman owned a beautiful little church that he used as a space to display some of his larger work and the work of students and colleagues. In October 2001 vandals broke in and set fire to the church, destroying it and its contents.]

N: Well, it was a blow. The collection was sort of a special one because it wasn't a collector's collection. It was an accumulation of pieces that friends and former students gave to me out of friendship, and it turned out that there were a lot of very interesting people in there. They were very meaningful. I had a sad experience the other day. Gloria told me that she heard Bob Turner died. He meant a lot to me. He was really my role model right up until the day he died. Now I don't have a role model. I had some of his work in that collection. I still have one piece of his, and I'm grateful for that. It was at the house instead of the church.

There were several other pieces down at the church, a series of tea bowls that he was trying out. Who knows if there are any more of them around? I had pieces by Ken Ferguson from the days when we were both starting out. There was a great deal of sentiment attached to that collection. They were all good pots. I had a little sculpture by Bill Parry, a little raku gem. There were some glass pieces by Dominick Labino, who was a friend of mine. I had so many pieces that represented his very early work, and that was coincidental with the beginnings of the whole modern glass movement. It was he, Harvey Littleton, and I that did all that early work. And that's gone.

S: It was such a shame for us, too, because we could come and look at those things and you could tell us about them.

N: That was the value of it. People kept coming down and I could show them those things and answer questions. And my own work - there were eight large steles in there, and two or three smaller ones, and I was hoping I would have them for income when I reached the point where I couldn't work any more. We're not exactly rich, you know, and those things might have provided us with some good experiences. Maybe we could take a trip or a little vacation. Sell one and we'd be covered. We'll have to do it differently now. Maybe it sounds callous, but I decided right there on the spot when we first came down and saw the church burned that I was not going to dwell on it. I was just going to go to work every day like I always do. For the most part I do, but sometimes I really miss it because one of the things that church provided was a way for me to look at my own work. I could go down there and look at it, position myself in relation to what I had made before.

S: What do you think about the retrospective of your work that's currently in Seagrove [at the North Carolina Pottery Museum]?

N: I think the smartest thing I ever did was to invite you guys [eight of Norman's former students] to participate in it, because that really made the show great. I'd like to be able to take credit for it, but I can't. I was happy to see my work, especially in light of the fact that so much had been lost in the fire. I was really glad to see there was enough left over to make a statement of my own development and movement. And I enjoyed seeing the pieces that were loaned by my patrons, friends, and collectors. I'm grateful to them for that. I especially enjoyed seeing the wood-fired work, because it is so simple, so understated. I had to laugh at myself. After all that work I'd done all through the years, putting all that effort into making these dramatic pieces, and then here are these quiet, earthy little shapes absolutely holding their own against the big ones. I don't know if they did or not, but that's the way I felt.

N: I think the smartest thing I ever did was to invite you guys [eight of Norman's former students] to participate in it, because that really made the show great. I'd like to be able to take credit for it, but I can't. I was happy to see my work, especially in light of the fact that so much had been lost in the fire. I was really glad to see there was enough left over to make a statement of my own development and movement. And I enjoyed seeing the pieces that were loaned by my patrons, friends, and collectors. I'm grateful to them for that. I especially enjoyed seeing the wood-fired work, because it is so simple, so understated. I had to laugh at myself. After all that work I'd done all through the years, putting all that effort into making these dramatic pieces, and then here are these quiet, earthy little shapes absolutely holding their own against the big ones. I don't know if they did or not, but that's the way I felt.

N: Yes, that's what I'm trying for now. Ever since I came down here, twice a year I'd have to shift gears, so the shifting of gears to make these recent pots was not so drastic. And it helped that I had to take time out from making to build that little kiln. A lot of shoveling of dirt, a lot of carpentry, and then brickwork, and more shoveling dirt. So there was a transition there.

S: How long ago did you build it? About three years? And Chuck Hindes comes down every once in a while to help fire it?

N: Yeah. Well, Chuck is responsible for at least fifty percent of the design of that kiln. He was doing a workshop at Arrowmont and it ended just as this conference started, a conference talking about older potters keeping on working as you get older. I was on the panel, along with MacKenzie and Cynthia Bringle. There was a big party to end the anagama firing they had there. I had in mind to build one of these things, but instead of using the Japanese anagama as my reference I was using the salt kilns that were built in

Kassel, Germany. They were long, low arches, sort of like the new wood kilns they're building today. I think they call it a "train'' kiln.

So at the party I told Chuck I wanted to do this and that I was thinking of having a firebox in front and entering through there. He got all excited, and he took my little sketch on a napkin and said, "I'll see you in a little while." He took off with the thing and made me a diagram of what I should do. It was interesting. I changed a couple of things, the stack and the firebox some. Instead of making it a straight-line arch I made a four-foot catenary in front and a two-foot catenary in back, just before it went into the flue. And the flue went into the stack, which instead of being a round or square chimney, was a wide, narrow one. The chimney is only four and a half inches wide inside by forty inches long, so it's like a flat chimney. I was doing the first firing alone, in July, and my daughter came over to watch and help. I'd been at it all night the night before, and working on it that day. Laura didn't like the way I looked so she called up Ken Sedberry, and he came up and wouldn't let me near the darned thing. When it got toward the end I had to use my authority. (Laughs) But it was a pretty good first firing.

The second firing Chuck and Don Pilcher came down in November, and there was rain and ice and snow. And you came up, and Ron Myers. It was a good time. That's one of the things I love about that little kiln - there's something about it that draws attention and people just come. Wood kilns do that. My life has always been very private and this is changing it. I love it.

S: (Laughs) Maybe I should look into that.

N: Come join me!

S: Shall we talk about the ceramics world today? Kind of a big subject.

N: Well, it's a good subject. It's possible to generalize, I guess. The primary thing, I think, is there's been such an advance in technology over the past thirty or forty years. Materials have gotten far more refined, but at the same time we've lost or used up good clays. When I started getting involved in colorants there were very few people using a lot of colorants. Those who were using them were generally those people out on the West Coast doing low-fire ceramics, and they were buying their glazes with colorants and painting them on. But then the color movement began, and there are a lot of people who want color but don't want to fire at low temperatures. They want to use engobes or glazes with colorants. This movement has caused a lot of experimenting. Mason Color, when I first heard of them, was an outfit dedicated to making colorants for the dinnerware industry. Industrial colors are a lot different from colors that potters use. NCECA has had a lot to do with the tremendous changes in technology. It did what we set out to do.

I was a charter member, at the very first meeting in Toronto. I think there were seventy of us there, due to the energy of Ted Randall. At that time it was the design section of the American Ceramics Society. A few of us were leery about it. After one or two years of being with them they were trying to get us to change our programs in schools and create designers for the ceramics industry. Now, everybody is not a designer for industry; it takes a particular talent, a particular bent of mind, to do that. There were a lot of independent, creative people connected with NCECA, and they were all trying to improve the situation. All together, there was a little bit of muscle there and we worked hard to cause it to grow. And so after about two or three years a couple of us got together and we rebelled. We withdrew from the American Ceramic Society and became NCECA. People started exchanging ideas. It used to be if you had a particularly good little wrinkle you could do, you kept it secret. We broke that down. We started sharing. There are a few secrets still around, but for the most part they are a sharing group. I'm proud of my NCECA contribution. I haven't contributed anything recently, but I had a lot to do with the beginnings of it, and I'm glad I did it. [Norman was president of NCECA in 1966.]

Well, Stanley, I've talked so much - I don't know of anything else. I'm sure when you walk out the door I'll think of something I should have said and haven't. The thing is I could call you up, but I'd forget it by then! (Laughs)

S: I think we've covered quite a bit. I really appreciate you sharing your time and thoughts.

N: I have one thing left to say. My wife and daughter have supported me all the way. When I left industry I left a very good job, one with a lot of promise to it. The money has never been the same, and there has never been a complaint from either Gloria or Laura. They've always supported me. They've enjoyed being part of the craft world, yet they've both been able to live their own lives. They're not dependent upon my life; I don't make a life for them. It may be that because of the nature of the way I work they've had to shift for themselves, but I don't think so. We have a good family, and that's been an important part of my work.

S: This has certainly been a wonderful place to hold this conversation, with the river in the background ...

N: And the thunder overhead.

S: It's a very peaceful studio you have.

N: Yeah. It's a bit of a mess, but that's life. I'm getting ready to start another body of work now. I'm going to pursue that goal of mine to eliminate glaze altogether, just work with clay, fire, and the ash it produces. And my hands. Continue the search for the essential, for the subliminal, for what's underneath. I like that as a goal. You know, it dawned on me while we were talking that I've spent all these years quietly working and thinking and forgetting. It would have been more wholesome - or more enriching- to have shared this time with others. In sharing, the motivation is there to keep you from forgetting.

Web editor's note: Norm Schulman died October 4, 2014; he was 89. See "Remembering Norm Schulman," compiled and introduced by Alan Willoughby, Vol. 44, No. 2, 2016.