Content Warning: Please note that this article contains depictions of violence, hate speech, and descriptions of racial slurs that may be disturbing. Please view the article notes for a description of Studio Potter's policy on digitizing archival issues.

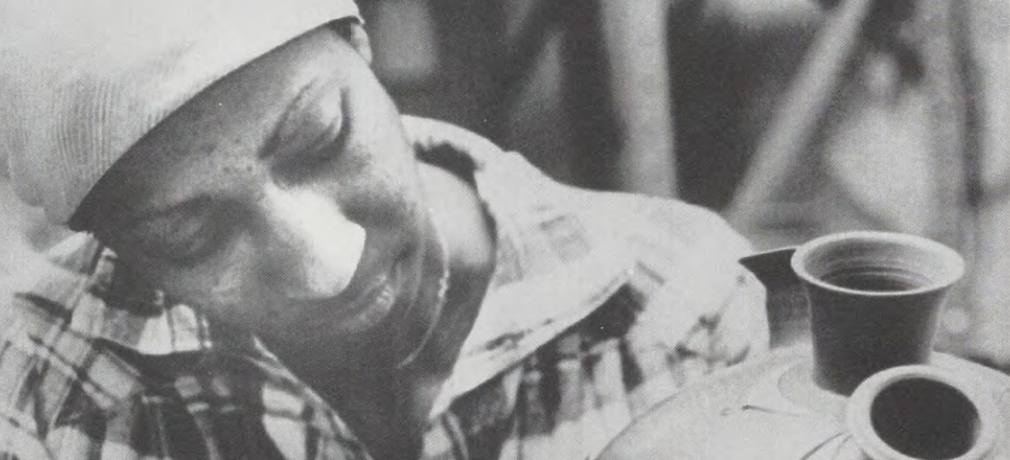

From the Studio Potter archives: North Carolina Potters – Vol. 26 No. 1, p. 25-39.

Early Life

I was born at Howard University Hospital, then called Freedman's Hospital, in Washington DC in 1949. My parents were George Charles Owens, Sr., and Mildred Cleo Gardner Owens. Both my father and mother worked for the United States government, my father in the Government Printing Office in Washington, and my mother for the National Security Agency in Maryland.

I was born at Howard University Hospital, then called Freedman's Hospital, in Washington DC in 1949. My parents were George Charles Owens, Sr., and Mildred Cleo Gardner Owens. Both my father and mother worked for the United States government, my father in the Government Printing Office in Washington, and my mother for the National Security Agency in Maryland.

My niece traced our family back to the mid-1800s. We are from the African American Bowman (or Boweman) family on my mother's side. Prior to that relate, we believe we will find the European part of the Bowmans. We haven't done much investigating on my father's side and can only go back to the Works Progress Administration (WPA) period.

I was brought up in Falls Church, Virginia, and later in North Arlington. In my early years, I went to the segregated James Lee Elementary School and later to the Langston Elementary School, again segregated. It wasn't until I was in the 7th grade that I went to an integrated school. Later I went to Washington and Lee High School in North Arlington, under integration.

Which usually meant one black and twenty-eight whites in the class. That was integration in Virginia.

Our cousin Nana was a cook at the all-black school. She used to make home-cooked meals that consisted of fried chicken, greens, yams, potato salad, and hot rolls for our school lunch. That's what we were accustomed to eating. Later, during my teen years, I took over my brother's former Saturday morning job, and I got paid to clean her house and also got fed. Cousin Oclclie (Nana's husband) and Poppa (Nana's father) ate at her house every morning for breakfast, as did the adult male cousins, most of whom were plumbers. She cooked corn cakes, pork chops, bacon, sausage, fried apples, grits, and homemade biscuits.

I remember the day the school system officials tried out a new menu on the students because it was supposed to be more nutritious. All the trays came back full. Nobody ate anything. It wasn't the food we were accustomed to.

I lived in the country (suburbs now) in a house with a yard around it. Ever since I was little, I always had my imaginary land. We lived near woods, and I enjoyed pretending that the woods were a great forest. When I was a little girl, my father gave me a small plot of land to use as my own. I actually tried to build houses on it, with swimming pools. I'd get a shovel and dig a hole and put water in.

I loved the water and could swim before I could walk, according to my mother. The public pools were segregated, so when we swam, we had to go to DC. I joined the swim team in high school because the pool where practice was held was segregated, and I was told I couldn't swim there. The county authorities, however, said that either she swims or nobody swims. I was fifteen.

I used to go to craft fairs. I remember going to the first Richmond craft fair, where I was the only black ceramics exhibitor. As I remember it, for a long time at NCECA conferences, Jim Tanner, James Watkins, and Richard Buncamper, and maybe two or three more African American students I did not know and I were the only blacks. White people would often come by at fairs and say, "You do ceramics? I've never heard of anyone black doing ceramics." I'd say, "Well, you haven't been around." Of course, I knew a lot of blacks doing ceramics.

Growing up, anything you wanted to do, you had to go to DC to do. That's one reason why I'm a Smithsonian baby. Every Sunday, it was the Smithsonian or the National Gallery of Art for me. When I was fifteen, I began borrowing the car. I went to church and then to the Smithsonian. My favorite museum, of course, was the Museum of African Art.

I led two lives in high school. I was the secret artist during part of the clay, and a jock the rest of the time. In my last year in junior high school, a certain boy was voted the most popular athletic boy, and I was voted the most popular athletic girl. There was supposed to be a picture of the two of us taken together for the yearbook, but the boy said he wasn't going to appear in any picture with a nigger. Because he refused to have a picture taken with me, it now appears in the yearbook with a dividing line down the middle where they had to paste two separate photographs.

My parents explained to me early on what to expect when the schools were integrated. They said, "Expect to be called a nigger, probably be spat on, maybe even hit." My mother explained, "If anyone calls you a name, it's because they're ignorant." So, I was more prepared for it in the 7th grade than I was later in college.

When I was twelve or thirteen, I remember we pledged allegiance to the flag every morning. One morning, the homeroom teacher told us to stand and pretend it was the Confederate flag and pledge allegiance. I knew what he meant and resented it. When I told my mother what the teacher had said, she was enraged and took off from work the next morning to read the riot act to him and the school officials. "How dare you make my daughter stand up like that!"

Well, you know what my life was like at school after that. How could they be so mean to a little girl? When I think of the movie Rosebud, I cringe at what people will do and have done in this country to other people because of color.

I'll never forget my seventh-grade art teacher. She made it possible for me to use the potter's wheel and to learn how to throw on it. I often stayed after school in the art room to work on things. So when it came time in high school to make a choice between art and sports, I said to myself that if I major in physical education and something happens to my body, it's the end of my career. But if I major in art, I can do art until the day I die.

In the eleventh grade I was accepted into the Richmond Professional Institute, now VCU School of Art. (I was also accepted with a scholarship at Cooper Union in New York but threw the letter into the trash because I hadn't even applied. I had no idea that you were chosen to go there and couldn't apply.) As it turned out, a story appeared that the KKK had invaded the campus of the Richmond Professional Institute and burned a cross in "honor" of the first black harvest queen. My mother said, "Find another school!" So, there I was in the twelfth grade, dropped from elite ranks of being a college-accepted eleventh grader, now looking for a school like all the other peons in my senior year.

Philadelphia College of Art

I applied to the Philadelphia College of Art (PCA) and was accepted. The tuition in 1967 was $2000 or $3000, unheard of at that time. My parents struggled for four years to keep me in that school. They hocked and borrowed everything they could to keep me there. The first year my mother wouldn't let me work. She said, “No, you just go.” My sister and aunt used to sneak money up to me. I never got a dime from PCA. I remember one of the administrators informing me, in a conversation we had in the hallway when I asked why I didn't get a scholarship coming from the high school as an honor student, that they stopped giving money based on merit because "you people" could never qualify. To this day, I hate the term "you people." I eventually got work study with the urging of a few good teachers. In my junior year, I was about to drop out of PCA because my parents just could not borrow any more money. I remember that one teacher who taught me in my freshman year set up an appointment with a Mr. Wolf, who gave me a scholarship to finish my junior year. Thank you both. The alternative was an acceptance and full scholarship to Penn State via another teacher at central campus, but at that point, I wanted to stay and graduate from PCA.

Quite frankly, it was my second taste of racism, the covert kind. When I came to PCA, there were 1000 whites and ten blacks. I'm thinking, “This is high school all over again.” My parents thought I was going for an art education. At the time, PCA had something called the Crafts Department, which was everything I could ever have wanted. I could get certified to teach and at the same time be a crafts major. I'm thinking I could learn how to blow glass, do furniture, do metals, and clay. I ended up narrowing it down to two majors, metals and ceramics. But they wouldn't allow two majors and fought me the whole time. It made my life almost impossible. Finally, they said since you insist on doing both, you will have to do all the work required for both majors, truly two separate majors.

Life was very difficult for me at PCA. At the same time, I had people in my corner like Leonard Leher and Doris Staffel (Rudy Staffel's wife at the time), Edna Andrade, Pat Cruser, Reggie Bryant (the only African American part-time instructor at the time), and a few others who taught me, just taught me without regard to the color of my skin or my immovable and often stubborn desire to become an artist against all odds.

I was on a mission. I was going to get an art education, and nobody was going to turn me around. I started a tutoring program in English for minority students because I learned that if they accepted minorities, they could get grants for the regular students. But often, academically unprepared students would get kicked out after the first semester.

I also helped start the Black Art Students Association. We formed a group and marched into the president's office, demanding to speak with him to urge him to accept more black students. I always stressed that applicants be qualified.

When you storm the president's office, you become some kind of target. Every year there was an award called the Liberal Arts Award, which was money given to the most outstanding academic student. Bernard Hansen, now an art critic and then dean of Liberal Arts, nominated me for the award. It was decided (by somebody), however, to split it up. I was furious because I thought they didn't want to give it to a black. I took the money, but I was getting sick of politics.

I was about to drop out of PCA because my parents didn't have enough money. There were several faculty members, however, who felt I was a good student and needed to finish. One of my foundation teachers told me about the Howard and Eudora K. Wolf Foundation and recommended I apply for money. I washed the clay off my hands and put on a clean dress, and went to meet the Wolfs.

Mr. Wolf was dressed to the nines and wore a flat summer straw hat. We had lunch and talked. I kept waiting for the academic questions, but they never came. Evidently, they had already made up their minds to give me the money. Which they did, and my mother was able to secure a loan from the bank to pay for the last year of school. Tuition was very expensive. I was in debt when I came out of school, but I had my degree in crafts.

During my last year at PCA, I got a job with the Iie Ife Black Humanitarian Center in North Philadelphia. My work began to change. Up to that time, I made cups, bowls, plates, and things like that, thrown with the thinnest of walls, which was what was happening on the East Coast. We thought what was going on the West Coast was bizarre. Why would anyone want to ruin a perfectly good plate by sticking fingers through it? Now I started changing the motifs on my work. My teacher called my work "primitive," meaning it in a negative sense. But I knew that technically my work was on par.

I was preparing for a senior show at a gallery on south street in Philly. There was a policy at PCA that if you didn't load your gas kiln by a certain time, you lost it, and anyone could load it if they had work. I always had work, so I loaded the kiln with my pots. The boy who was supposed to use the kiln came in and cursed me out, accusing me of taking his kiln. He grabbed a big wooden paddle he used for hand building and threw it right at me. I went to call the police and have him arrested. One of my ceramic teachers took me into the courtyard and talked me out of calling the police. To this day, I think I should have called. To my knowledge, they never reprimanded the boy. He should have been expelled. They never acknowledged his wrongful deed, and he never apologized. There are many ways messages of worth are sent.

For our senior crit, the faculty brought in a person from New Jersey. I put in all my African-inspired work and one European-looking pot because I liked its glaze and shape. This person went around picking out every one of my African-inspired pieces and criticizing them for being crude. I knew how well-formed they were technically. This guy was really zinging me. My classmates and one of my instructors would not look at me. I held my head high, though, because I was proud, as I was raised to be, of what I knew I had aesthetically and technically achieved and did not need external validation.

Then this person went over to my European piece and said, “Why couldn't the person who made this pot use the same sensitivity and skill to make the other pots?” Well, a light bulb went off in the students' heads. They looked at me dumbfounded. And the very person who had thrown that big paddle at me because of the kiln incident came over and said, “Do you want a knife?” I said, “For what? Excuse me, I've got to get to work.” Because I didn't talk about it, I guess they thought it had gone over my head. So, when I left PCA, I promised myself never to be subjected to that kind of treatment again and vowed I would never set foot across the threshold of an institution of higher learning for the rest of my life. Of course, that changed.

Howard University

Howard University was founded by General Lee, a white general, to educate blacks. Howard, Hampton, and Tuskegee were normal schools. Their mission was to train "negro" students to be nurses, bricklayers, masons, industrial designers, and agriculturists. Originally, they did not train students to be scholars. Today Howard's reputation is built on medical and law schools; its reputation is international. A great number of the famous standard bearers of color in the world have gone to Howard at one time. The level of education is as good as you can get anywhere, even though it isn't an ivy league school by other standards. It has always been an integrated school, with Native Americans as well as blacks.

Howard University was founded by General Lee, a white general, to educate blacks. Howard, Hampton, and Tuskegee were normal schools. Their mission was to train "negro" students to be nurses, bricklayers, masons, industrial designers, and agriculturists. Originally, they did not train students to be scholars. Today Howard's reputation is built on medical and law schools; its reputation is international. A great number of the famous standard bearers of color in the world have gone to Howard at one time. The level of education is as good as you can get anywhere, even though it isn't an ivy league school by other standards. It has always been an integrated school, with Native Americans as well as blacks.

I had applied to Howard when I was in high school but was rejected. My cousin had been accepted a year earlier, so I was leery about applying again. But then I saw an article in Ebony magazine about their new president and their increased black consciousness and the murals on the walls of buildings that showed art was really happening. Donald Bird was in the music department, and Lloyd McNeil was doing art. So, I said, “Ok, this is it.”

I received a full scholarship to attend Howard. Now, for the first time in my life, I was studying African American art history and learning about other black artists. It was such a rich experience. I began to be exposed to African fabrics and started wearing traditional Ghanaian and Nigerian dress. I joined the dance group. I met people such as Charles Searles, now a famous artist, and Barbara Bullock, who had just received a Pew Foundation grant in Philadelphia.

I graduated from Howard with an MFA in ceramics and sculpture. My sculpture teacher, Ed Love, and I became great friends later on. I made a lot of ceramic sculptures but wasn't getting any critiques from the ceramics instructor. I got most of my critiques in the sculpture class because their sessions were really spirited and raised the level and quality of the dialogue and the work.

Traveling

I taught metal and ceramics jewelry at the Ellington School for the Arts in a pre-program for careers in the arts. It was the best teaching job I ever had. Debbie Allen taught dance, and Mike Malone was the director. Many people who taught there are now very well-known in their fields.

I started traveling while I was at Ellington. I had read about Buckminster Fuller's map, and it really made sense to me. It showed that at one time, all the land masses were joined together and later broke apart. Thus, we became different people. Everything went back to clay for me. I said, “Well, if there was a woman, there was a pot being used and pottery being made.” So I began looking at historical pots in museums, looking for pots with round bottoms and motifs. There were African pots with round bottoms and motifs, as well as Oceanic ones and Egyptian ones, all indigenous with round bottoms and similar motifs.

Once in Oregon, I saw a pot, and I couldn't tell whether it was African, Oceanic, or Indian. It was a Mimbres pot. I was floored. I said, Wait a minute, there's something here. Could you prove that there was a relationship between African ceramics and Indigenous American ceramics?

I had a little 1971 Volkswagen beetle and, together with two girlfriends, decided we would start on the East Coast of the US and travel down to Mexico to the Yucatan peninsula, come back up the West Coast of the US, and return to Virginia.

Mexico opened up a whole world of ideas for me. Once, we were in Guadalajara and drove down a little road because someone told us about a place with tiles. We stopped and knocked on a door, and when it was opened, we saw that the piazza was just covered with tiles, every inch gorgeous, with a fountain in the center. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. I was in heaven at the Anthropological Museum in Mexico City. I saw an amazing mural depicting women in transition. It blew my mind. On the left was an African woman, and as the mural turned, the woman changed full front with her complexion brown and with straight hair – a Mexican woman. Then she turned again and ended up on the right as a white woman with blond hair, her back to the viewer. Perhaps it was their idea of evolution?

Unfortunately, our car kept breaking down, and we were never where we were supposed to be. We broke down for the last time as we were entering LA. I just gave up and lay down in the sand and looked up at the stars.

Africa

I had a burning desire to go to Africa, just to know what it was like to go back to where I came from. But I was discouraged by a teacher who lived across the street. Oh, you don't want to go there, she said. I thought to myself, “That's your opinion.” Once I get an idea in my head, it is pretty difficult to get it out. Basically, my attitude is to find out for myself.

When I was fifteen years old in high school, we had units: a fabric unit, a painting unit, a jewelry unit, and so forth. For the final project, we had to combine all the units. I made a man. My Daddy found a cardboard refrigerator box tall enough for me to make into a life-size cardboard cut-out with a stick behind so it would stand up. I proceeded to dress him in a loin cloth, painted the fabric, made clay beads for jewelry, dyed cotton to make his hair black, and painted him to look like a human. My teacher was flabbergasted. I earned an A.

In college, if I found a person who looked like me and had an accent, I would come right up and say, “Where are you from?”

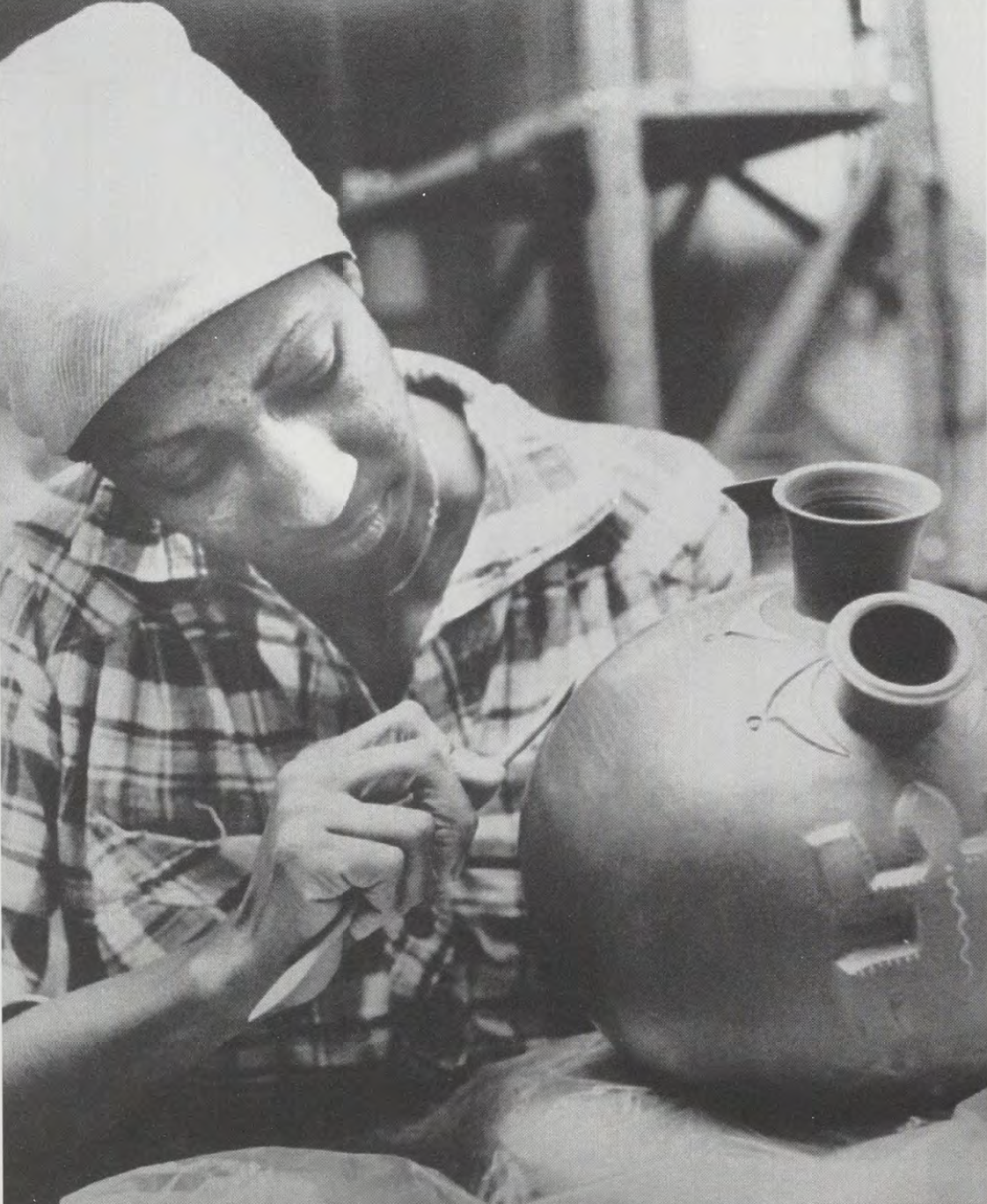

When Ladi Kwali, the well-known Ghanaian potter, came to the United States for the World Craft Council, I followed her around like a little puppy. I also met Michael Cardew and Kofi, who traveled with her. Once, when I worked at the Iie Ife Black Center in Philadelphia, I saw a film by a German filmmaker on African women making pots. I watched the film at least a hundred times, or until I thought I had learned their technique. I made a huge pot that impressed everybody and took it to be fired in the electric kiln at the Center. It blew up, but I had the technique down.

Years later, I got a job teaching in Howard University's Art Department. While I was there, I learned about a festival to be held in Lagos, Nigeria, called African Festival of Art and Culture (FEST AC). Basically, it was for any person who had ever come from Africa, historically and currently, to return and meet there and celebrate the arts – music, dance, drama, visual and literary arts. People came from every country to share in the celebration at FEST AC City.

The American group's trip was sponsored, in part, by the U.S. State Department. We stayed in the village and traveled during the day to various festival activities. I had two pieces in the exhibition, one of which was a drum. There was an opening for the exhibition, and we met other artists. At night everybody would mingle. People always ended up in our section. They considered us (Americans) the top in terms of economics, education, per capita income, quality of living, fashion, and musical contributions.

I met a famous sculptor named Agbo Folarin at the FEST AC. He was from Ife and offered to take a few of us there. I said This is uncanny; I worked at Ife in Philadelphia, and now I'm going to the real Ife. He took me to Ipetumodu, where I thought I had died and gone to heaven. It was my lifelong dream to go to an African village and do ceramics. As it turned out, they were doing exactly the same technique that I saw in the German-made film.

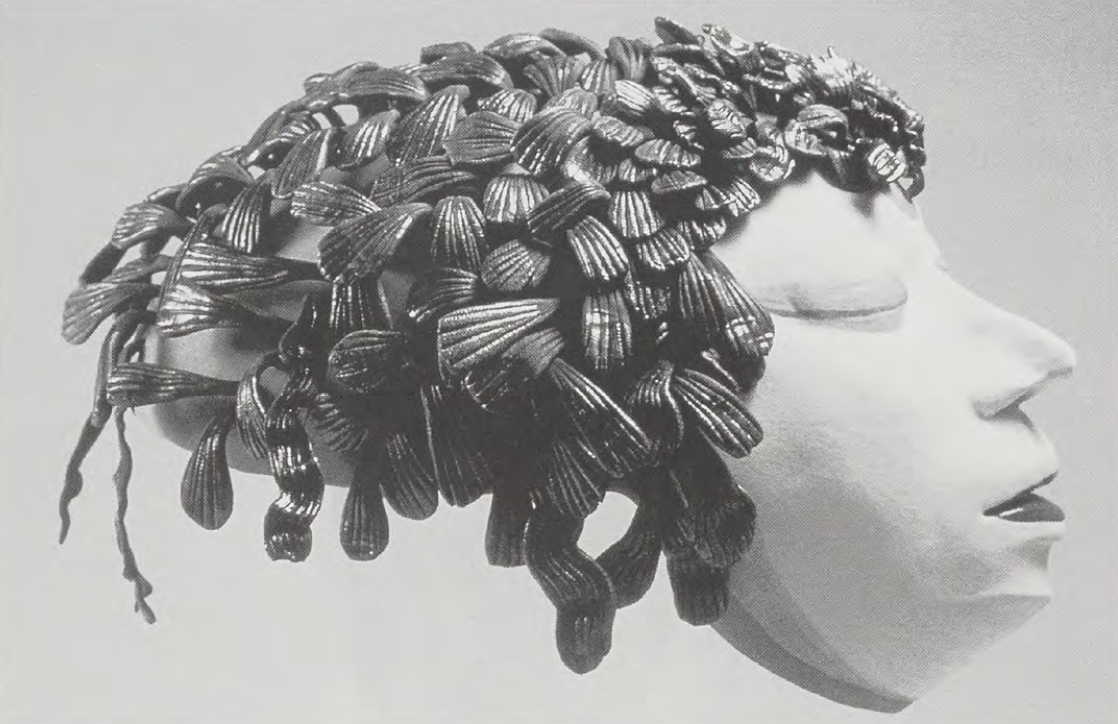

Folarin introduced me as a potter from across the water. My hair had been braided into a traditional Yoruba crown so that when I walked into the village, I had the right hairstyle. I wore a tie-dye dress from Togo with a leotard top and earth shoe sandals and carried a Pentax camera over my shoulder. I started right in building a pot because I thought I knew the technique. But I didn't. When I added my clay to their pot, the women immediately took it off. Even at that, they thought I was really a Nigerian who had just gone away for some time and had recently come back. The women were wonderful to me, though, and never made me feel strange or unwelcome.

I returned to Howard University and found I had won a National Endowment for the Arts Craftsmen Fellowship grant of $5000. Again, I thought I had died and gone to heaven. I bought a kiln, a wheel, an extruder, and a ticket back to Nigeria.

The women of Ipetumodu worked six days a week, sunup to sundown. The work produced was utilitarian, vessels to eat out of, to store things in, cook out of, and drink from. Basically, they made the same shape. Each woman had an ebu or workshop. The pottery center was located within the interior section of the village, while the market was on one side.

I apprenticed to a woman named Alice (pronounced "Elesa"). When I first came, the arrangement was that I paid a sort of tuition and was to be taught pottery by all the women, a ward of the village. In reality, it was Alice who was my home base and primary teacher. Traditionally, you are born into it, or you are taken there by your parents and work with a potter until you are fifteen or sixteen years of age, at which time you have the skills to open up a little ebu of your own. I was the wrong age, into my twenties, not married. I was looked at as an African woman who should have been married and had children.

At the time, I was teaching ceramics at the University of Ife, now called Owolawa University. When I wasn't in class, I caught a lorry in the morning out to the village to help the women make pottery. The first thing the potter did was to make half of the pot over a mold form. The molds belonged to the village. She picked the size she wanted and could make different sizes during the day. First, she made a flat pancake by stepping on it with one foot, while walking around it in a circle. Then she spread ash on the mold and inverted the pancake over the mold, walking around it, first patting it, then hitting it and beating it with a stone from the apex, spiraling her way down to the edges. The clay spreads out evenly. Then she took a corn cob and rolled it on the clay for texture and, with a sharpened stick, cut off the bottom evenly. Then she picked up the wet clay and set it on the ground in the sun to stiffen before receiving the rounded section of the vessel.

The halves made the previous day were ready to invert in a basin of sand or dirt and to begin building upon. In her hand, she rolled a piece of clay into a fat kind of knockwurst. Then with the piece of clay wedged into her hand and holding it perpendicular to the side of the pot, she would smush it and turn it and walk backward at the same time. She kept repeating this process until she ended up with a flat wall about the same thickness as the bottom half. It was done that way because that's the way the women did it. I asked intellectual questions and the women's answers were always: Because my mother's, mother's, mother did it. It was the tradition.

At that point, the apprentice handed over the tick-tacky clay to make the lip coil. This is a very soft clay because it has to move under a wet cloth. It's just like throwing on the wheel with a chamois, but instead of its turning in front of her, she walked around it.

In the end, the potter put her signature around the neck of the pot. To me, it looked like a design but might have been what we call a trademark or logo. In America, we sign our pots on the bottom; there they sign on the neck. Some historians have said that traditional African art is anonymous. The women of Ipetumodu have a history of signing their pots. I suppose what is missed by a historian is an understanding of their codification system.

The final form depends on the mold they start with. They know which mold is right for which pot. Each shape has a specific name. The one I remember most vividly was the only one I ever saw with a dent in the bottom so that it could sit on a table. It was the palm wine pot, shaped like a jug, a little round on the bottom and bulbous in the middle. It came up to a neck, not too narrow, because they dip their gourd in to take out a drink.

If there was to be a firing that day, they would then load up the kiln. The kiln was a circular adobe structure and, depending on the diameter, with four or five burner ports made out of the lips of pots, through which to place bamboo logs to fire with. They loaded the large pots first, upright, then stacked progressively smaller pots until the pile came to an apex, and covered the whole load with shards to keep in the heat. They used a dung wick to start the fire, then stoked with huge bamboo logs that could be pushed farther in as they burned. The firing took two or three hours, in intense heat. They knew by sight just when the kiln was finished firing. The burning bamboo was pulled out and dowsed with water. They unloaded the kiln while the pots were still hot.

In the meantime, the bark of the ira tree had been soaked in water to produce a juice. It was my job to receive the hot pots with two flat sticks and roll the hot pots over to the lady who sloshed the ira juice over them with a bush brush made of various leaves. I think the juice had the purpose of being decorative, as well as being a type of sealant, although I never specifically asked that question of the women.

After each firing, the women and their children would come and pick out their pots, to take them back to their workshops to be sold later, usually to market women. Or perhaps they were filling an order. I used to go to the huge Thursday market in Ife, but I never saw any Ife pots. I certainly saw pots from other areas with different shapes and designs. I suspect they took the Ife pots elsewhere.

When I first came to the village, there were perhaps twenty-two potters. When I returned for the summer, there were still at least as many. At some stage, before I left, the number was reduced to fifteen. They were not selling well enough to make a living, due to the importation of plastics and enamelware. When I returned the third time, there were only twelve potters left, and from what people have told me, there are now progressively fewer and fewer. The economy has become a lot worse. As in America, you buy pots/artwork with disposable cash, so it could just be basic economics as to why it isn't working for them. Ipetumodu was a small pottery village compared to others. It was tucked away, and you have to know where it is to find and purchase pots. The only people that I knew for a fact that were still using pottery out of necessity were the soap makers; they needed the porosity of the pots to make their soap.

It is my life's mission to go to every African country and learn about techniques, document them, and bring them back to America. Historically, African ceramics is as old as Chinese and Japanese ceramics. Of course, it doesn't have the glory of these two cultures in ceramic history because not much has been written about it. If you really want a clear picture of ceramics, however, you have to include all ceramics. Otherwise, your view will be lopsided, and you will be making incorrect assessments about the people who make clay objects and have contributed culturally and technically to the field and the world.

At any school in the country (except perhaps Howard), you get the impression that African Americans had nothing to do with the development of ceramics in this country. In fact, exactly the opposite happened. If it wasn't for the African American input to ceramics in this country, it would not be where it is today.

When ceramics students in America look at me they think I'm an oddity, that Jim Tanner is an oddity, that Watkins, MacDonald, Tucker, Carpenter, Jackson-Jarvis, and so many others are oddities because we're African Americans, when in reality, our people came from Africa, worked in clay before they were hauled aboard boats, and made clay objects when they came here under the most deplorable conditions. Anthropologists and historians are beginning to support this notion. The truth is that Africans brought the knowledge of the art with them. African Americans ran or were major players in some of this country's major potteries, especially in the south. They were the turners, they decorated the work, they fired the kilns.

An anthropologist named Leland Ferguson at the University of South Carolina found shards around the living quarters of Africans when they were captives. They couldn't have bought the pottery, so they must have made it. Hence, there seems to be evidence that colonial ware must be recognized as encompassing pottery made by Africans and Indigenous Native Americans.

Teaching

I have been teaching for twenty-eight years. I am a full professor at Howard University in Washington, DC., teaching ceramics to undergraduates as well as to graduates and to the occasional drop-in or drop-out. I also coordinate and teach a 3-D concept program in the foundation studies program for incoming and transfer students. It is safe to say that I'm the only professor in the United States who has a unit on African ceramics in which students have to make a pot using traditional methods. I also teach a course called “Tradition,” dealing with non-Western traditions in handling clay as done in African and Indigenous American ceramics.

In the early 1970s, I was chosen as a monitor for an African session at Haystack School of Crafts in Deer Isle, Maine, to assist Abbas Ahuwan of Ahmadu Bello, northern Nigeria. It was a wonderful African session. It was my dream to have someone from Africa come to teach and make African ceramics. I met several African American artists at that session, including Martha Jackson-Jarvis, Denise Ward Brown, Yvonne and Curtis Tucker, and Delores Harris.

Haystack was a wonderful experience and is my second home. I gained a lot of technical information at Haystack, and it was a major influence in changing how I worked, from Western methods to African. Previously, everything I did was essentially on the wheel. If hand building, it was usually slab or that waste-of-time Western coil method, which just doesn't make any sense to me now.

I believed then, as I do now, that I needed to be knowledgeable on the topics of all ceramics, Korean, Japanese, Chinese, Aboriginals, French, English, and Spanish. So, I decided to study with traditional American potters and went to ldyllwild School of Music and the Arts in ldyllwild, California, to study with Blue Corn. Blue Corn, a San Ildefonso potter, is such a wonderful person, a gentle spirit. The forming and firing techniques were incredible. When I returned home, I immediately built a firing pit with a welded grate. My students made some lovely things. We didn't have bear grease, so we used lard, but it worked, and the pots came out shiny black. The students would have cut off your hand if you had touched one of their pots.

At ldyllwild, Blue Corn taught us to start by making the pot in a puki, let it dry completely, then return and sand it. Then rub on a slip and put bear grease right over that and immediately burnish it. I was always taught slip had to be formulated to fit the body, but after I saw Blue Corn. I said to myself, “Okay!”

I haven't incorporated American Indian techniques with African techniques but keep them separate. I would like to say this, however, that when I was doing research on early American ceramics, Professor Leland Ferguson was a great source of information. I once asked him if there was any evidence that African captives who ran away to join Indian reservations could have been potters and possibly influenced their ceramics. He replied that there was, in some instances, a marked difference in the pottery after Africans started interacting with Indigenous Americans. I know this is a very sensitive subject, but there is a possibility that somewhere there is a pot actually buried here that might support this theory.

I also taught at Penland. It was a new experience for me because Penland is in the mountains, whereas Haystack is beside the ocean. What's especially important at teaching environments like Penland and Haystack is that there is no pressure whatsoever from sources such as faculty meetings. It's a very intense experience, of course, but it's clear what you're going to do. You're in and out, three weeks maximum. My daughter especially loved Penland because they had a school for children. She was in seventh heaven with the other kids, creating and experiencing the natural surroundings. They had great teachers, too.

My Work

I see myself involved in two distinct lines of work. At PCA, I was trained to throw plates, bowls, cups, and vases. I learned to throw tall, thin cylinders. I aimed at technical perfection. I was also hand-building with hard slabs. I still do all this today; that hasn't changed.

What has changed is my perception of what I do. In the beginning, I had to justify what I did as a ceramist. The pressure was on to be profitable. Some galleries encourage sculpture instead of pots because they reason they can justify charging the client more. Herein lies the schism in the ceramic world. The message is: go in the direction of sculpture because you can get more money for it. It is the higher art. Thus, money values have been placed on art. Young people have bought into this. Working on the wheel takes quite a bit of time and practice to develop great skills. But this is the fast generation; people want everything quickly and don't invest in the time to be skillful at the wheel. I tell my students, however, that they must perfect every technique if they want to use the clay for sending messages. Art is about transference of information from your head to your hands to the materials of choice, then to the viewing public. If you are not trained to transmit that message, you have a problem. This means you learn how to mine clay, how to throw on the wheel efficiently, how to hand build flawlessly, how to calculate glazes everything. You go to every workshop you can and expose yourself to every display of ceramics that exists. And you never stop looking.

I make traditional Nigerian drums. They are primarily percussion instruments. The drum has two holes on the side of the pot. Some are round with no protrusions; some have necks at the top. You play them by intermittently hitting one side, which pushes the air out as sound. Then you cover the top so as to either allow the notes to be intermittently released or stopped completely. The speed with which you hit the holes determines the beat and pitch.

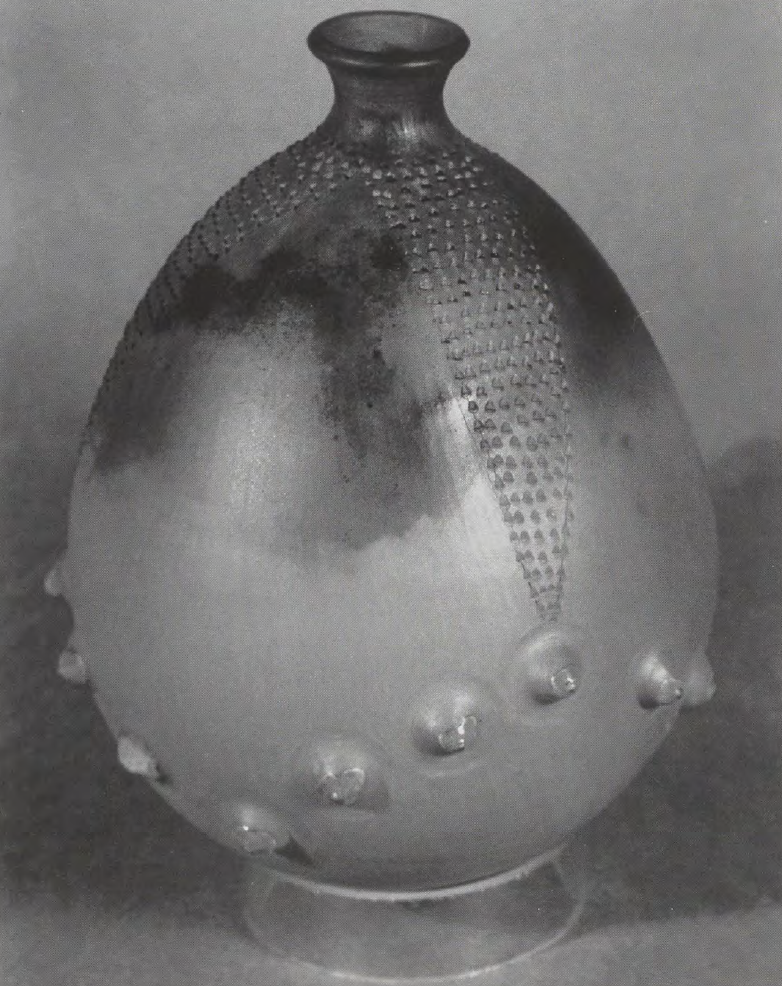

Currently, I sawdust-fire my pots in one of two smoke pits, a small one and a large one. I had a grate made for the traditional Pueblo firing technique. I use low-fire clay to form the traditional pot, then biscuit fire it. Usually, I put a glaze on certain areas and fire the piece in a regular kiln. Then I go back and put a commercial luster over the glazed areas, leaving the rest unglazed, and refire it. Finally, I place the pots in the pit and sawdust-fire them. The sawdust is tightly packed if I want a deep black or loosely packed if I want flashing. The pit smolders overnight. The next morning, I pull them out, and they are either reduced or randomly flashed.

Currently, I sawdust-fire my pots in one of two smoke pits, a small one and a large one. I had a grate made for the traditional Pueblo firing technique. I use low-fire clay to form the traditional pot, then biscuit fire it. Usually, I put a glaze on certain areas and fire the piece in a regular kiln. Then I go back and put a commercial luster over the glazed areas, leaving the rest unglazed, and refire it. Finally, I place the pots in the pit and sawdust-fire them. The sawdust is tightly packed if I want a deep black or loosely packed if I want flashing. The pit smolders overnight. The next morning, I pull them out, and they are either reduced or randomly flashed.

Sometimes I place little bumps on the surfaces of the pots. For me they are scarification marks, like the skin decorations that African and other indigenous people use as a form of adornment on their bodies. It's always interesting to read what critics say about this. One male critic writing of my work called the bumps "tits." That showed where his head was. They were certainly not big enough to be breasts. Why would anyone use the word tit? Scarification within traditional societies is a sign of adornment and beautification.

I have an electric kiln inside the studio and a gas kiln outside. When I lived in Alexandria, I applied for permission to fire my kilns, but no one in the licensing department knew what a kiln was. They called it a "kennel for dogs". I said, "Kennel for dogs? No, a kiln. K-i-l-n." The spelling didn't sound like the pronunciation. I explained, "You fire pots in it." "Fire?" they asked. "Oh, no, you've got to go to the fire department." I finally got the permit for the kiln. And it's a good thing I did because the first time I fired at night, my neighbor called the police and fire department. Then she called the licensing people, but everyone had heard about me by that time.

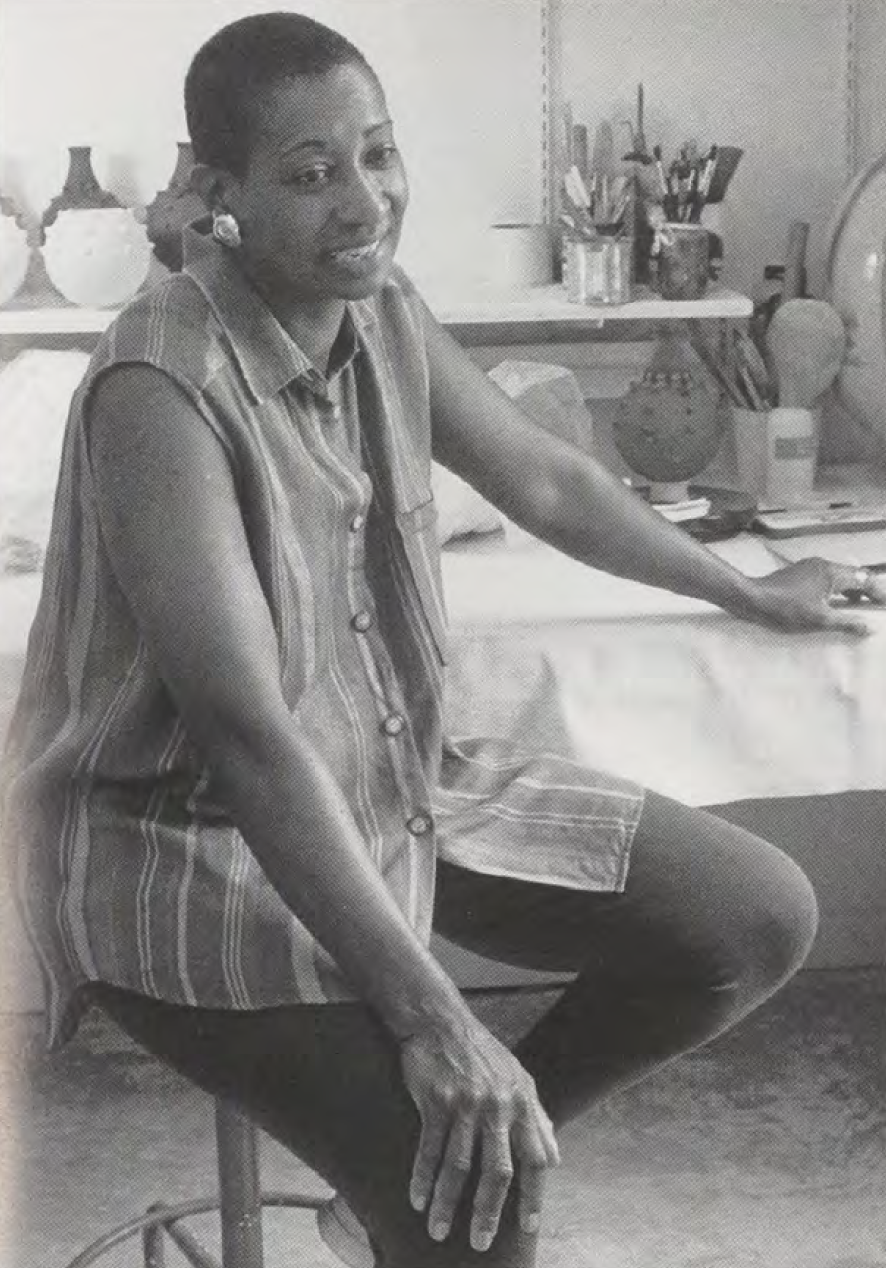

My Studio

If I could teach for the rest of my life, I would be happy. But what I really want to do is to have my own place and teach there. I used to think I had to teach at Howard to accomplish my mission, but long ago, I realized that I needed to expose myself to people of all colors to dispel negative myths and misinformation. My mission now is to get the message out about Africa and African American ceramics.

For years I made sketches of houses. When I lived in Nigeria, there was a particular U-shape style of house that I thought functioned well inside and outside. The sleeping quarters were on one side, the kitchen and pantry on the other, and in the middle the living and dining room. It formed a natural courtyard and was a one-story structure. I thought, I could build this myself, and I said, “Okay, let's find some place in the country.” I'll go by myself and make pots; I won't be bothered by anyone. My husband, however, wanted a two-story house, so we went that way. Eventually, I want to construct an authentic little Nigerian pottery village/ebu for people to experience when they come out here to do workshops. I'm going to build my traditional Nigerian kiln soon, too.

While I was in Nigeria, my real estate agent found a piece of property in Gainesville, Virginia, that was just the right price. I returned home and found that it was still available. I made an offer, and it was accepted. It was just what I wanted. It had a cute little pink house with a fireplace, living room, bedroom, kitchen, and bath. There was plenty of room to build a studio.

All my life, I have worked in basement studios. I've carried tons of clay up and down steps and tracked mud alI through the house. Once when I was doing a luster firing in the winter, the fumes from the kiln were sucked into the furnace vents, and I almost asphyxiated my infant daughter sleeping upstairs. I vowed to never again have a studio underneath the living space.

I've always been a solar nut. I have as many books on solar energy as I have ceramics books. That's how this house design came up. I have a Trombe wall in the studio and solarium. The south side is glass, and the heat comes in and warms up the concrete floor and the Trombe wall. There will eventually be solar shades in the windows, to be closed at night so the heat being emitted from the Trombe wall does not go out through the windows. There is an electric heat pump as a back-up system, and ceiling fans and towers. The house is comfortable because it works well.

The architect and I designed the two-story structure with a 6/12 pitched roof. Everything in the design of the house is based on a working studio. To the left is the studio, to the right is the living area. The studio is self-contained with a loft above for visiting artists.

I wanted this house to be built entirely by African Americans because there is a general notion that this is not possible. I did not quite succeed because there were no well diggers or panelizing companies that I wanted in this area. But that was my mission. My mother says I go overboard, but I say it's basically an economic consideration. The reason African Americans are not doing as well in the marketplace is not due to a lack of desire or skill in most cases. Usually, it is due to not enough opportunities. I am a ceramicist. If I manage to pay for an education and become very proficient at what I do, and I manage to get the banks (or someone) to lend me the money to set up a studio, and I make the perfect pot, no one will buy it if it is not seen in the right place. If I am not accorded an opportunity to market my perfect pot it will never be sold, and if it is not sold, I will never be able to repay the loan to set up the studio, and I will thereby lose the studio.

Of course, this could be any young person's situation. But it is reality and not a case of crying over spilt milk when I tell you first-hand that all opportunities in this country are not accorded to us all equally. It has nothing to do with anyone being on the short end of the stick or "being lazy." Many people think I'm attacking whites when they hear me say things like this. I'm not. It's simply an affirmation of who I am, a belief that anyone who looks like me can do well and has done well historically. Earlier it was the effects of captivity, then segregation (which still exists defacto). Now the mass media does its part in controlling the truth. The American media does not reflect the truth about its populations as they truly exist and function successfully in this country. The media is a very powerful tool, a tool that has become such a part of our everyday life that we do not realize how facts are spun and the truth manipulated because it is done so well. Despite what continues to swirl around me, I affirm who I am as a woman, as an African American, and as a human being.

The Pink House

The house next to my studio is a 25x25, one-story frame bungalow. The people who built it put pink siding on it. Over the fifteen or more years that I have owned it, I have rented it out to many people.

The house was vacant for some time because my cousin and I were renovating it. I had never advertised its availability except for a "For Rent" sign out in the front next to the highway. The house can't be seen from the main road, but many people came to inquire about rental.

I always kept a list of people who came asking about the rental, so I made a record of the couple who came to see it that day. The man said he was a carpenter and worked for a deck company but was soon going out on his own. He was tall and wore a scarf on his head. The woman looked very pleasant. They were a calm, peaceful couple. I looked them over and asked how old they were. "Twenty-one," they said. I asked them to fill out an application and give me their financial status. Well, they had no credit history, but the girl said she had three jobs, and was trying to get back the custody of her daughter. I called later to check on her and, indeed, she did have the jobs. I was impressed. I thought of myself when I was growing up, always having two or three jobs to reach my goals. I said to myself, “They need a break; I'll give it to them.” So I told them I would give them a lease, but only for six months. She said her dad would cosign. They came back later and executed the lease, all very polite and mannerly. He didn't have much to say; she did most of the talking.

One day as I was up on a ladder fixing the upstairs bedroom window of my house, I looked down and saw a sea of skinheads in the yard. My heart started to beat rapidly. No, no, no, I said to myself, this couldn't be! This doesn't make any sense. Skinheads don't want anything to do with black people.

I calmed down. I thought to myself, “They were very cordial... they couldn't be...?” But I began to notice from that time on that I caught them in some untruths. One thing led to another, though not enough to alarm me. I noticed the man had taken off his scarf and walked around skin-headed.

One day they came to me and said that the refrigerator was broken. I have a cousin who works on refrigerators, so I called him. When we returned to install the new part in the refrigerator, I came into the house through the front door instead of the back. The tenant tried to stop me, and I soon saw why. From floor to ceiling on three levels were cages of snakes. There was a king snake, a python, a boa constrictor. Just like in the cartoons, I threw the part up in the air and practically ran him over on my way out of the door.

I said, "What the hell is going on here?" I reminded them that they had signed the lease that excluded pets. Then I saw another side of her. She came up to me and said, "Those aren't pets." I said, "If they're not pets, what are they?" "Well," she said, "he breeds and sells them." But they didn't get rid of the snakes.

Toward the end of the six-month lease period, I was lying in bed one day when the burglar alarm went off. I called the police, and they came out to the house but decided it was a false alarm. Then the police said to me, "Do you know who those people are over there?" I said, "Yeah, they're my tenants." They proceeded then to tell me about the trouble they had had with them in town. A third man that I had seen around the house had been picked up by the sheriff, and he told them he was living at my rental place.

I hit the roof. I walked over and said to them: "You can only have two people on the lease, and the police tell me there is a third person." "Oh," they said. "He's just staying here until his parents return from Panama." It turned out he was living in a tent in the woods.

Then I started checking into things and began to realize that the whole arrangement with me was a set-up. There were lots of things that I see in hindsight that should have been flags for me. So many things that I went to the sheriff and asked what I should do. He told me to get an eviction notice. I served them with an eviction and a no trespassing notice. When the deputy came out to serve them, they muttered something about niggers, and Jews and spicks to him. He was so disturbed about it that he came back later on his own time to make sure I was ok.

Shortly afterward, my husband Jim was helping me put up a fence, and I looked up to see the man charging across the yard, screaming, "Nigger, nigger, fucking nigger!" It scared me to death. He stopped when Jim stood up. If my husband had not been there, he surely would have finished his assault.

By this time, I had hired a lawyer because I was getting no place with the police. I called the lawyer immediately, and he told me to go down to the magistrate and file an assault warrant. But the magistrate refused to issue it because he said the man didn't get close enough. I said that if he had gotten any closer, I wouldn't be here talking. They said I was a hysterical woman. I wasn't hysterical. I said, "These people are dangerous. The guy came after me." I told him that they had hung a swastika in the window. I said, "This is a historically black neighborhood."

We went to court. We had brought two rows of supporters into the courtroom, plus two bodyguards from DC. We didn't know what to expect. The accused man and woman came in late and sat right in front of me. The man knocked on the bench with an iron cross ring during the whole session and talked constantly. He Sieg Heiled the judge when he was being sworn in. The judge did nothing about that, but the man was convicted of curse and abuse.

Afterward, we were standing outside in the hall when the man started to come toward me. My lawyer was there watching, and the man stopped when he saw the people around me. Because of this, the deputy sheriff (my guardian angel, just a wonderful person) later kept coming back to my house to see if I was all right.

Because of alI of the things he had done against me, a stalking charge was issued by another magistrate. The man was sentenced to six months in jail but released after only three months. For a long time afterward, every time I came back here from teaching at Howard, I expected to get a bullet through my head. I lived with all this for four months before we got them out of the house.

That was two years ago. It became a celebrated case and was on Channel seven, a local news station, and written about in the Washington Post. It was a big media event before, during, and after the case. And it was a historical case. It was the first time in Virginia law that a person was convicted of stalking based on racial harassment. He can't come anywhere near me, and if he stalks me again, it's a felony.

My black neighbors and the NAACP think that this couple were here to run me off my property. They figured that if they could run the youngest one off, they could run everyone else off, too. A black neighbor in the community told me this neighborhood has a history of klan attacks. He said, "We didn't move in the 1800s, and we're not moving now."

I think all this would have stopped cold if the cop had arrested them the first time; then, they would have known I was serious. If the magistrate had issued the assault charge, which was a jailable charge, it would also have stopped. If people had done what they were supposed to do along the way, this would have been stopped. Through the escalation of events, apparently, they felt the system was on their side. And I felt the system at one point was on their side, too.

They were just two nuts, but two nuts who are part of a growing group of people who harbor hate. They hate anybody they can. It just so happens that in this country, historically, your skin color makes you a good target for people who have other frustrations. It's ludicrous. I've worked like a dog since I was fifteen years of age. I've earned every penny that has ever come into my hands. So I have the right to buy what I want and to build what I want. This is America, isn't it?

Postscript

During the Nazi regime in Germany, Martin Niemoeller, the Protestant churchman, said: When they came for the trade unionists, I said nothing because I wasn't a trade unionist. When they came for the Jews, I said nothing because I wasn't Jewish. When they came for me, there was no one left to speak for me.

My position on all this is that if you don't stand up for what's right, then you're standing up for what's wrong or lying down for what's wrong. I think a lot of white people don't get it. I hear young white people say, "We don't know anything about slavery because we didn't do it." I say, "You would never say that to a Jewish person because the Jews never forget. Black people should also be saying, Never forget." What I'm saying is that you (every one of us) should make sure it never happens again. I see it welling up in this country. People are falling silent. They said Nazi Germany can never happen in this country. That's a lie. It can happen very easily here.

My position on all this is that if you don't stand up for what's right, then you're standing up for what's wrong or lying down for what's wrong. I think a lot of white people don't get it. I hear young white people say, "We don't know anything about slavery because we didn't do it." I say, "You would never say that to a Jewish person because the Jews never forget. Black people should also be saying, Never forget." What I'm saying is that you (every one of us) should make sure it never happens again. I see it welling up in this country. People are falling silent. They said Nazi Germany can never happen in this country. That's a lie. It can happen very easily here.

The myth has been perpetuated and reinforced. I fear for what's going to happen. It's ridiculous to have so much hate. At the same time, there are many white people who stood up; I had many phone calls and letters from them. I know my faith in God brought me through this more than anything else.

Each person has to examine where she or he is on this issue. Many people say that they don't see color, and I used to say that in high school. But racism is a very scary thing. At one point in my situation, I was petrified, but I was left with no choice. Someone once asked me why I rented the house to skinheads. I said, “Excuse me, do you think I would have rented it to them if I knew who they were?”

There are many myths floating around in this country. Those myths divide us and make us hate each other. In my case, I was a victim. Many people came and apologized for the behavior of those people and asked me not to think that all white people were like that. I told my daughter after the incident that you must judge people by how they treat you. Color and gender don't matter. How they treat you is the measure. If you do dirt to someone, it will come back to you two-fold. That's my karmic code of living. Also, there but for the grace of God go I.

I'm happy with who I am, and I clearly understand what informs my work. The artistic part of my life is making clay objects and firing them. But we cannot separate our art from daily living. These things and more have happened to me; I didn't make them up. They happened by virtue of circumstance but mostly by virtue of the color of my skin. And I'm going to talk about it. Why should I hide it? The people who perpetrate such acts didn't hide it. Unfortunately, it's part of this country's fiber. And thereby, a part of the ceramics field. It's part of the craft field, it's part of the art field, it's part of the world.

The difference can only be made by you and me.

NOTES

Studio Potter (SP), working in conjunction with diverse communities, will seek to balance the preservation of its history with sensitivity to how SP’s archival materials are presented to our readers. In the process of deciding to digitize this archival issue in its original form, SP sought the guidance of the author, the National Archives, and The Archivist’s Taskforce on Racism Report. The SP archives may contain some content that could be harmful or difficult to view. SP’s archives span fifty years, and it is our charge to preserve and make available these historic articles. As a result, some of the archival materials presented may reflect outdated, biased, offensive, and possibly violent views and opinions. SP engages in an ongoing process of review to ensure that our operations, policies, programs, and strategic direction work toward dismantling structural racism.

Share

Share