How Removing Distance Can Bring Us Closer to Answering an Age-Old Question

I teach ceramics in the School for American Crafts at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), where my colleague Jane Shellenbarger and I have been revising our curriculum. One of our goals is to create more opportunities for ceramics majors to engage with others throughout the Institute. Rather than separating these cohorts – as we’ve done in the past through outside elective courses for non-majors – we’re commingling them so ceramics students can benefit from the perspectives of science, engineering, mathematics, and liberal arts scholars. Those non-ceramics majors, in turn, can benefit similarly.

I teach ceramics in the School for American Crafts at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), where my colleague Jane Shellenbarger and I have been revising our curriculum. One of our goals is to create more opportunities for ceramics majors to engage with others throughout the Institute. Rather than separating these cohorts – as we’ve done in the past through outside elective courses for non-majors – we’re commingling them so ceramics students can benefit from the perspectives of science, engineering, mathematics, and liberal arts scholars. Those non-ceramics majors, in turn, can benefit similarly.

Students interested in the arts must navigate complicated questions like: where does creativity originate, and how is it historically referenced within our contemporary activities? It is invaluable to do this in close company with those whose experiences challenge the beliefs and assumptions present in our own.

The legacy of intellectual property is weighty and often emotionally charged. However, as an educator, I find this subject to be of the utmost importance to all individuals who wish to work with clay. It is my belief that we can provide much-needed objectivity and help minimize the emotional nature of these conversations through a series of introductory, studio-based courses for the broader student population.

I’ve developed such a course with the help of Associate Dean Christine Shank and Art History Professor Sarah Thompson. Titled Josiah Wedgwood’s Legacy, the course offers an introduction to the interpretation of ceramic art history and uses object-making to help students understand a significant moment in time. The course examines the evolution of eighteenth-century European ceramics under the influence of Josiah Wedgwood’s innovative spirit.Through a combination of research-based exploration and hands-on, immersive experiences, students learn about the impact of ceramics manufacturing on social dynamics and class hierarchies, business practice, mechanical innovation, the division of labor, and Neoclassical style.

It is RIT’s first studio-based, object-oriented general education class and can fulfill an early course requirement for any student, within or outside the College of Art and Design. It is open to all, regardless of prior experience.

Generally, the goal of a studio-based course is to develop technical skills. However, Wedgewood’s Legacy was designed chiefly to help students understand the complicated nature of ideas and how they evolve. A key to this was exploring pottery’s distinct influence in the age of imperialism. By understanding this era, we aimed to grasp how innovation and appropriation have become intertwined, if not indistinguishable, within the fabric of ceramics culture.

Generally, the goal of a studio-based course is to develop technical skills. However, Wedgewood’s Legacy was designed chiefly to help students understand the complicated nature of ideas and how they evolve. A key to this was exploring pottery’s distinct influence in the age of imperialism. By understanding this era, we aimed to grasp how innovation and appropriation have become intertwined, if not indistinguishable, within the fabric of ceramics culture.

Wedgwood’s Legacy debuted last fall to a motley crew. The course drew upon the whole of RIT’s student population. Clay people worked alongside those from a range of disciplines, from the closely-related field of Industrial Design to distant ones like Theater Arts, Entrepreneurship, Anthropology, Sociology, and Public Relations. The students had just three commonalities: they wanted to touch clay; they wanted general education credit; and they hadn’t a clue who Josiah Wedgwood was.

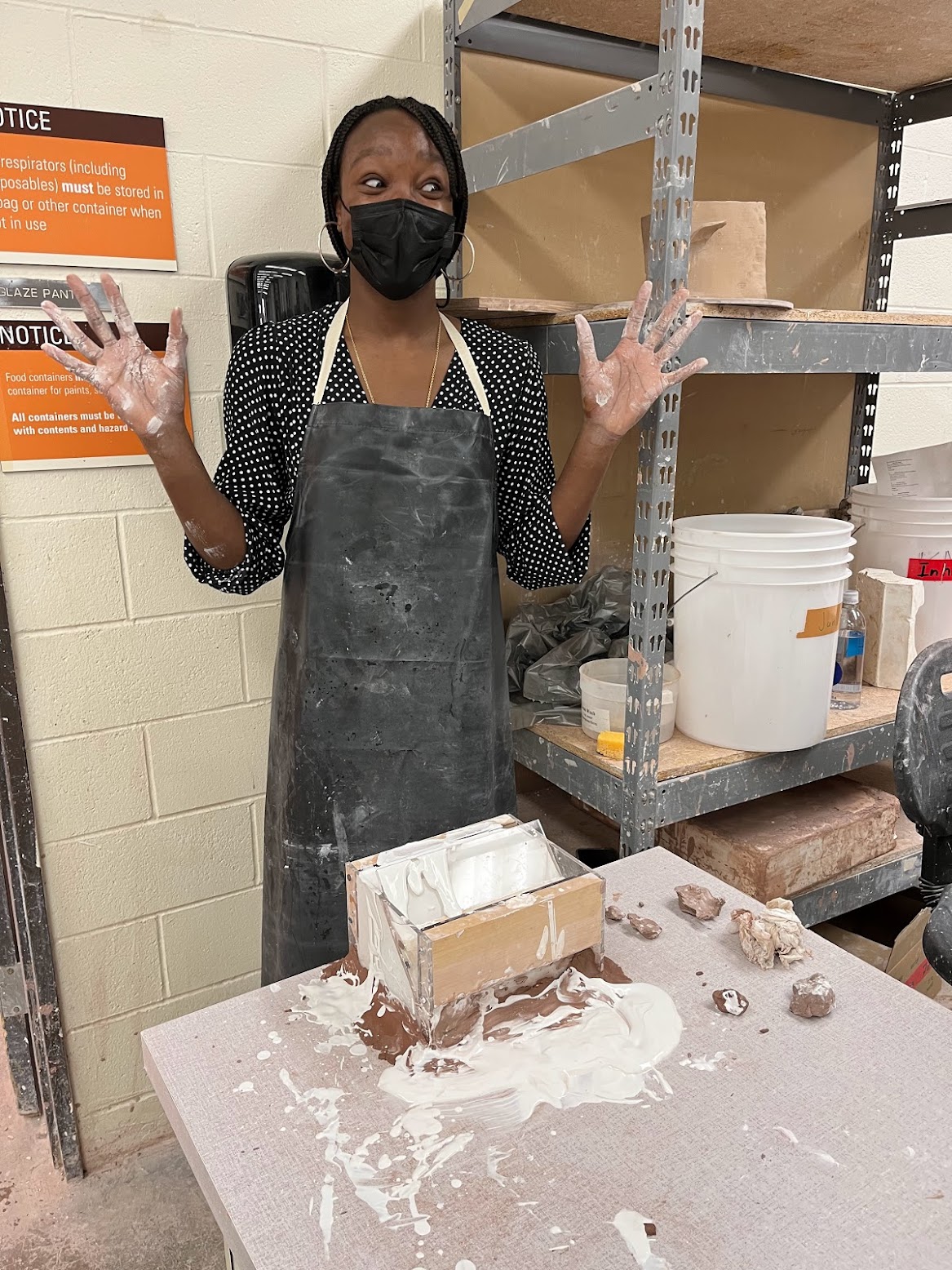

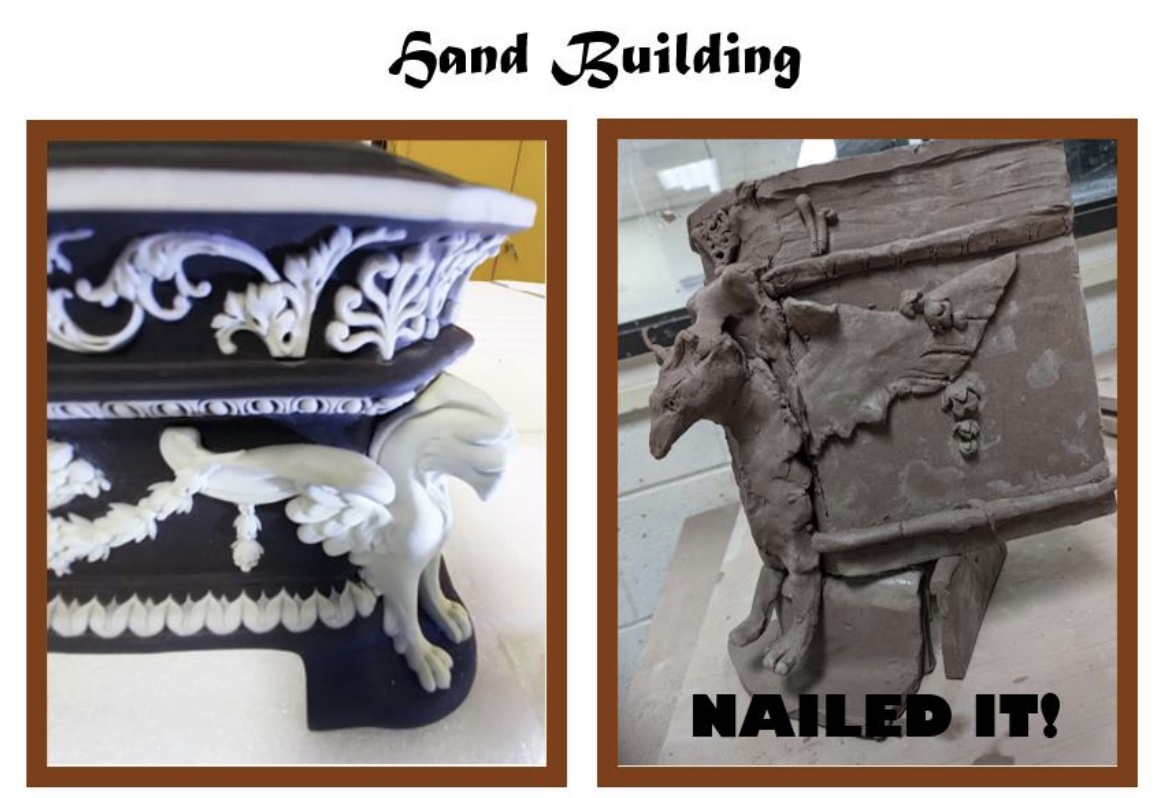

We began lightheartedly. The fundamentals of throwing, hand building, and forming plaster were presented through a speedy exercise inspired by the rambunctious hit Netflix show Nailed It! In that show, novices attempt expert baking challenges. Their outcomes are typically disastrous. Similarly, I built studio time around overly ambitious tasks within artificially frantic and tight deadlines, asking students to replicate a handful of Wedgwood’s masterfully articulated moments in, on, or of vessels. On the whole, the group lacked substantive experience with clay in much the same way as those who dare sign up for Nailed it! Ever so brief demonstrations were provided – each no more than ten minutes and with little to no verbal instruction — before they battled the prompt of the day.

We began lightheartedly. The fundamentals of throwing, hand building, and forming plaster were presented through a speedy exercise inspired by the rambunctious hit Netflix show Nailed It! In that show, novices attempt expert baking challenges. Their outcomes are typically disastrous. Similarly, I built studio time around overly ambitious tasks within artificially frantic and tight deadlines, asking students to replicate a handful of Wedgwood’s masterfully articulated moments in, on, or of vessels. On the whole, the group lacked substantive experience with clay in much the same way as those who dare sign up for Nailed it! Ever so brief demonstrations were provided – each no more than ten minutes and with little to no verbal instruction — before they battled the prompt of the day.

As our premise mirrored the show’s, so too did the results of our efforts. Things that were not slipped or scored fell apart; crude articulations represented highly-refined, sculptural objects; lumps of soggy clay showcased little more than the reality of one’s first shot at throwing. All of this was expected, forecasted, and celebrated. We took time to understand the concept of being new to a tricky discipline in the face of studying a potter who was at the top of his game.

Despite the raucous event advertised above, readings, writings, and discussions defined the quality of the experience — and showcased the value of commingling students. Those whose ambitions centered on clay had a technical advantage, and their subjectivity helped newcomers take on otherwise daunting prompts. On the other hand, writing and discussion brought forth distinctions between how each student saw concepts like apprenticeship systems, the purpose of higher education in art, the value of skill in clay culture, and the impact of social media on early stages of creative development. In these instances, non-majors had fresh, objective perspectives on the discipline that challenged those of dedicated majors.

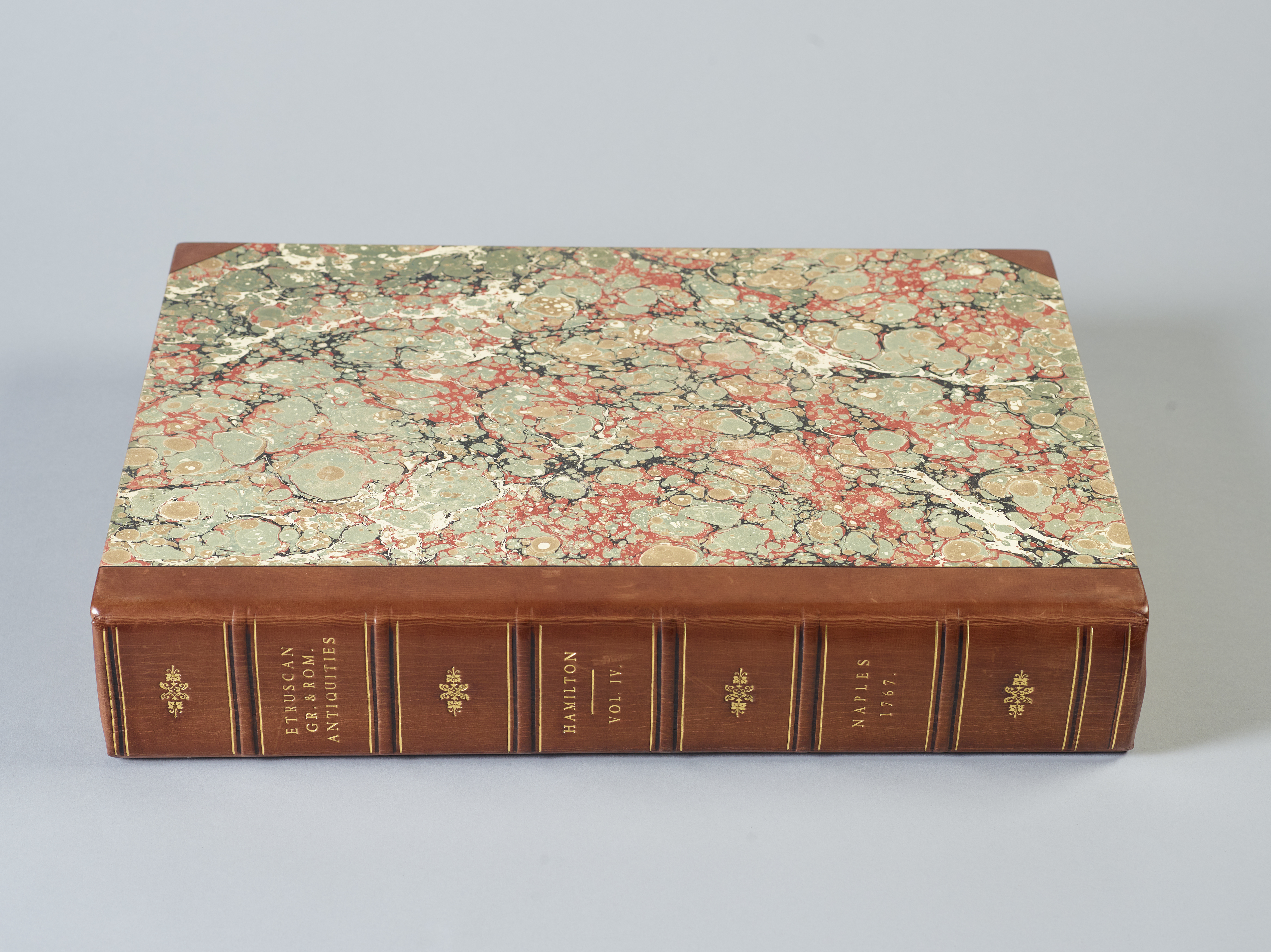

Nailed It! led to a robust exercise named Revisionist Antiquities, which involved a deep dive into The Complete Collection of Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honorable Sir William Hamilton. We spent the rest of the semester unpacking this book and Wedgwood’s unique relationship to it.

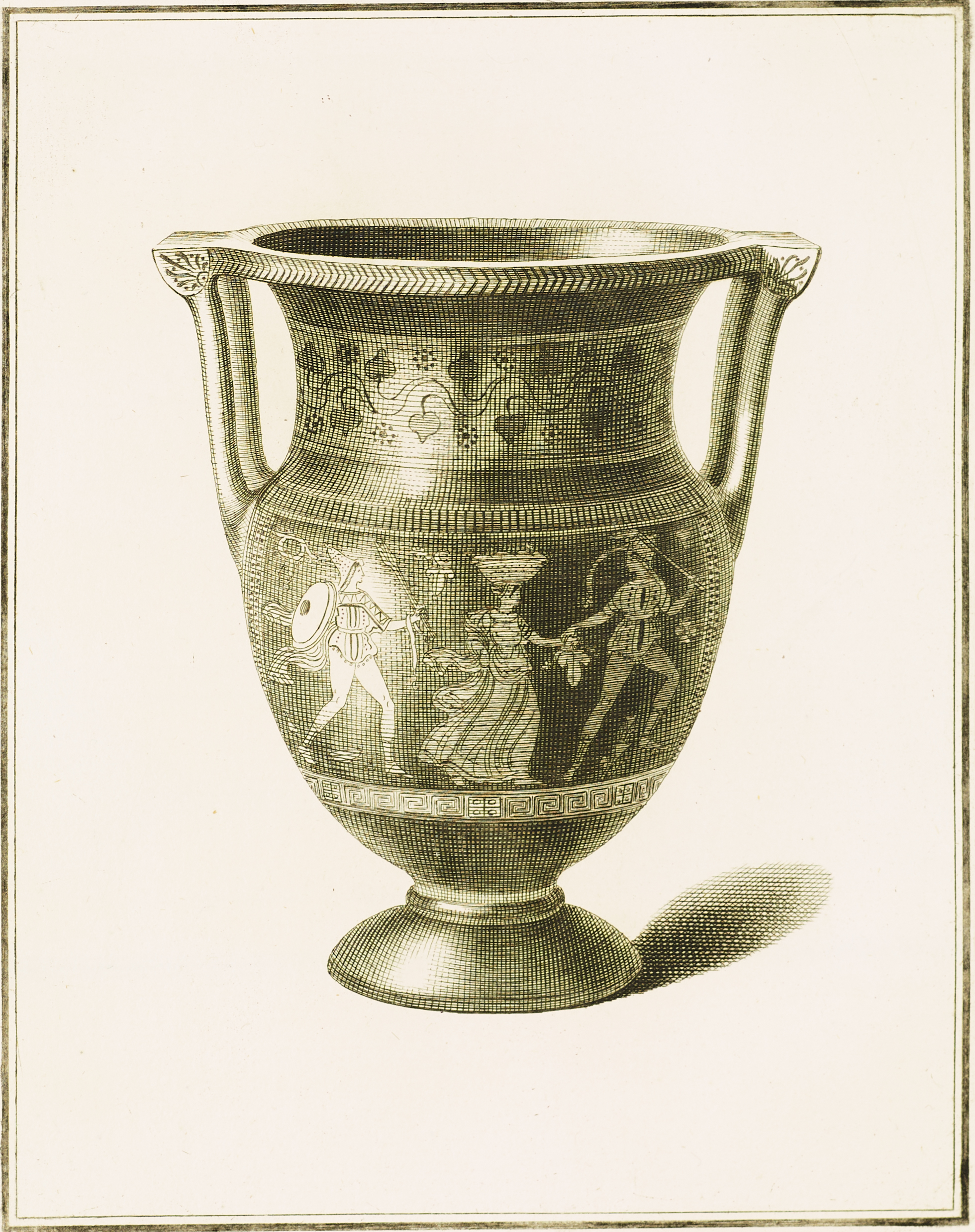

The book — a five-hundred-fifty-page tome printed on hefty 18 x 12” paper — archives the considerable Greek vase acquisitions of its eponymous wealthy collector, Sir William Hamilton. Originally commissioned around 1767, the book not only fastidiously renders hundreds of gorgeous forms but also offers a visual account and blueprint of ancient Etruscan pottery. In the eighteenth century, the whole of Europe became consumed by a desire to own these treasures after regions of Tuscany were excavated to reveal ancient Etruscan burial grounds. Demand seriously outpaced supply. As is always the case with coveted objects, only the wealthiest could afford what was available.

Wedgwood saw this supply problem for the opportunity it presented. He dreamed up a collection of new Etruscan-esque vases, virtually indistinguishable from their predecessors. He subjected age-old vessel archetypes to new industrialized processes, technologies, and business practices, increasing their quantities to meet the demands of a wider audience. He too would diversify what he made to suit the exquisite tastes and scarcity mindsets of the high-end collector. Thus, the potter created a multi-tiered marketing strategy on the foundation of a rebirthed Etruria.

Wedgwood saw this supply problem for the opportunity it presented. He dreamed up a collection of new Etruscan-esque vases, virtually indistinguishable from their predecessors. He subjected age-old vessel archetypes to new industrialized processes, technologies, and business practices, increasing their quantities to meet the demands of a wider audience. He too would diversify what he made to suit the exquisite tastes and scarcity mindsets of the high-end collector. Thus, the potter created a multi-tiered marketing strategy on the foundation of a rebirthed Etruria.

He knew his Greek vases better than the competition because he had access to The Complete Collection of Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honorable Sir William Hamilton. He studied it meticulously to build near-encyclopedic knowledge of classical aesthetics. He made clay and glaze formulas to reproduce the book’s contents. In 1769 he opened his new manufactory, Etruria, and on its front steps revealed modern Greek pots to the world, dubbed his First Day’s Vases.

In contemporary discourse, it is generally understood that appropriation is a destructive co-opting of culture for personal gain. Some might argue that in creating those vessels, Josiah Wedgwood was engaging in such activity. However, I believe that perspective is reductive and too simplistic considering the true nature of Wedgwood’s works and the vast implications they hold for anyone who has made a clay pot since.

The purpose of Revisionist Antiquities was to interrogate that

element of his legacy while engaging in a rich study of the original items from The Complete Collection of Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honorable Sir William Hamilton.

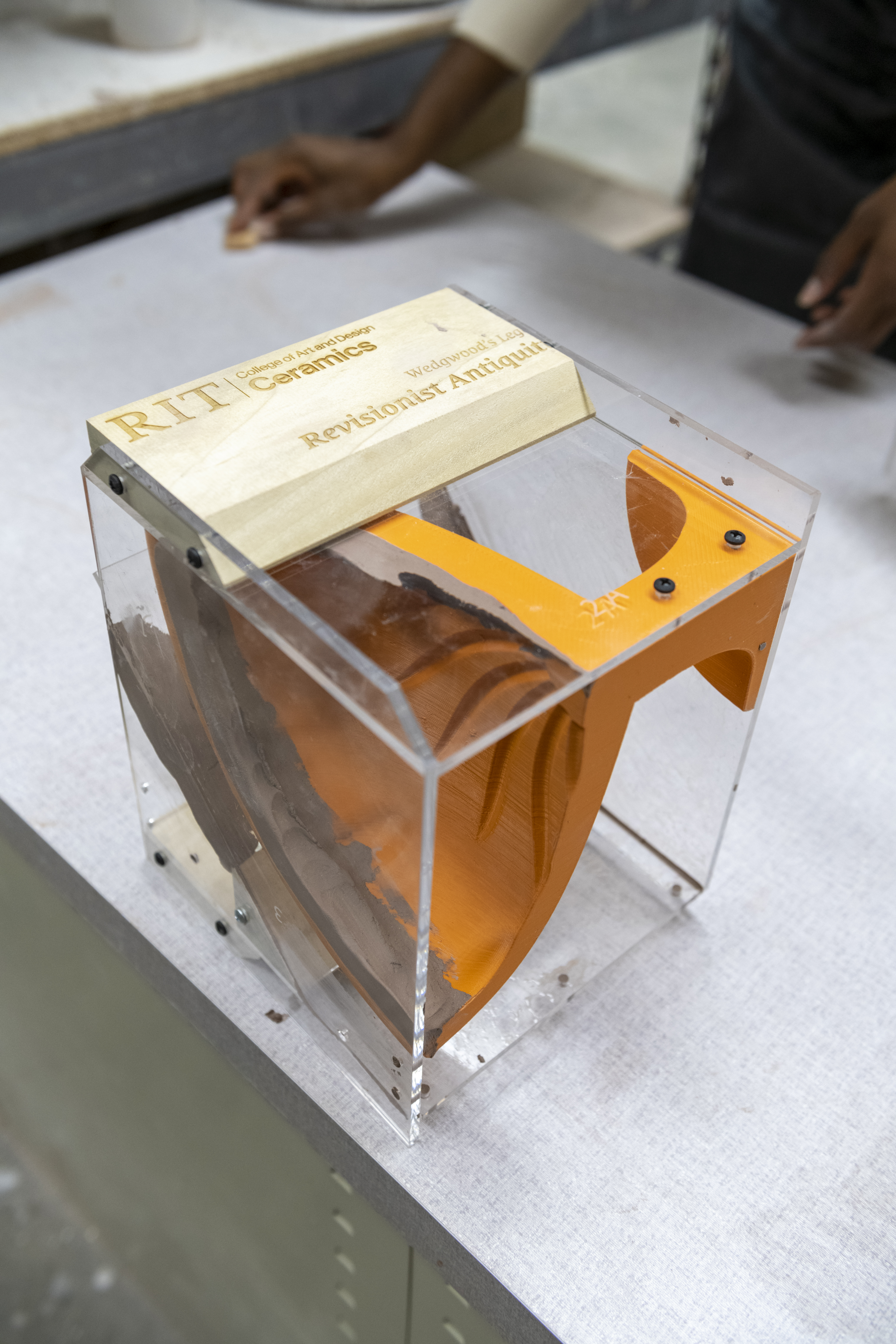

I designed the studio element to decrease the distance between Wedgwood’s abilities and our own. Whereas he developed technologies to aid in the reproduction process, we used “new” ones to supplement a collective lack of experience. We plucked images from the book with our smartphone and digitally rendered objects from them. The results were printed in plastic alongside customized laser-cut acrylic cottles. We molded our prints and cast clay objects from the molds. Little to no skill was required to bring those vessels from print into the digital and finally on to the table.

As they made their molds, I again engaged students in reading, writing, and discussion. However, this time each student’s research was compiled into a robust lecture on their chosen Greek vessel and subsequent reproductions of it, including their own. The defining question was if or how such reproduction, including Wedgwood’s and their own, changed the meaning of the original — and if the changes were positive or negative contributions to it. As students attempted to walk in the footsteps of Wedgewood and actively replicate antiquities through technological means, they grappled with the ethics of doing so.

Definitions of theft, plagiarism, and appropriation became vital to this evolving dialogue — and again, the value of commingling showed itself. Each student, of course, had a distinct opinion on the question of morality that came from how intellectual property boundaries were drawn in their respective discipline. But collectively, the cohort agreed that learning from imitation was vital to understanding this discipline.

An unexpected discovery further strengthened this belief. I had standardized every project’s height to avoid unnecessary frustrations caused by ambitious oversizing. As I demonstrated the casting process, a student suggested I merge two different sets of molds. They noted that this standardization provided an opportunity to not only invert one, two, or three of the sides of their own objects, but also to combine their molds with others from the class. Doing the math, an engineering student quickly determined that there were tens of millions of new objects to be discovered through mixing and matching.

As students traded mold segments, they witnessed influences blending with their own curiosity. One discovery led to the next. What began as outright copying became a fascinating series of experiments in shape, composition, and complexity. Were they plagiarizing or appropriating? They didn’t think so. They bought the experience as it was sold to them: an academic exercise designed to bring them closer to an eighteenth-century potter whose work expanded exponentially the more he invested in studying classic form.

Of course, it helped that they were not being graded on what they made.

But students in the rest of my courses are – they must negotiate that space between their ideas and the question of where their ideas originate. Once they graduate, they will have to do this on their own to function in a field that is increasingly concerned over the preservation of intellectual property. I believe an introductory course like Wedgwood’s Legacy can help them engage in a healthy way with their influences as they develop their own creative practices. It achieves this by decreasing the distance not only between students and history, but also between majors and non-majors.

Combining students from a range of academic research areas, each with unique perspectives, with Wedgewood’s legacy and complex thinking made for a rich and unusually spirited experience. Bringing students so close to potential impropriety did as well. This was terrifying, but less so than the fear of avoiding the conversation — or worse, forbidding them to engage with history in a field so tethered to its own legacy. Fortunately, all involved come closer to understanding the foundations of their own creativity. Because where innovation expands from influence and something new comes from something quite, if not too, familiar is where most potters must live and what they must learn to respect.