Fear of Failure as a (Gasp) Positive Indicator

In 1966, when was graduating from high school on the south side of Chicago and headed for the Kansas City Art Institute, I remember telling my friends and classmates - quite unabashedly - that my goal was to become as famous as Pablo Picasso. Well, everybody's got to start somewhere, and I am now quite sure that Pablo is in no danger of being eclipsed by Richard Notkin, ceramic artist. (Perhaps if I had remained a painting major...) So, rest in peace, Mr. Picasso, and thanks for leaving behind such a wonderful contribution to twentieth century art.

Forty-five years later, if I still adhered to this adolescent goal, I would be quite miserable. Our culture, and many other societies of this world we inhabit, places an inordinate amount of value on such things as fame and fortune. If only we could become rich and famous, how successful - how happy - we would be. So goes one of the superficial mantras of our materialistic world.

Real success, however, requires discovering the right reasons to live. For this artist, success has come to mean something far more valuable and rewarding than my early notions of worldwide acclaim and a deluge of big bucks. As the playwright George S. Kaufman put it quite succinctly, "You can't take it with you." I won't knock fame as irrelevant, however, for I do recognize its value in my own artistic pursuits. A bit of recognition, or even notoriety, can help artists to sell their art and can provide the means to continue working in their studios. But I also know that fame is not the Holy Grail to a contented life. If one really wants fame, one should leave the dusty life of the ceramic artist behind and head to Hollywood. Thankfully, one can be at the very top of the charts in the world of the ceramic arts and still walk through an airport without sporting a big hat and oversize sunglasses, or the fear of being assaulted by autograph seekers and paparazzi.

While fame and fortune might become the rewards - or spoils - of success in the field, there are far more substantial goals an artist should pursue. Understanding and coming to terms with one's passions, one's reasons for creating in the first place, should be a prime goal. Developing nearly infallible techniques in your chosen medium is also necessary to be able to create works that are capable of expressing these passions and concepts. As soon as these essential elements are established, an artist merely has to place himself or herself at the mercy of inspiration.

Sounds easy. But it's not. On our journeys to become and to remain artists, difficult experiences are inevitable, and we all desperately want to avoid failure. But what is failure, exactly? In essence, I suppose that failure is living our lives for the wrong reasons.

For the dedicated artist, time in the studio is the most valuable asset. It takes time to think, to study, to experiment, and, finally, to create meaningful works of art. The finite time we are allotted while we experience the inexplicable miracle of our lives is our greatest tool, our most valuable material, our only true possession. As an independent studio artist for the past twenty-six years, I have had to use my time judiciously, structuring my life to maximize my time in the studio, where creativity is a solo endeavor. These years of self-imposed isolation have allowed me to spend a great deal of time contemplating the elements that culminate in the creation of art.

All artists, at every stage of their artistic career, work within a given set of limitations, both aesthetic and technical. Artists with the greatest capacity for growth and evolution in their work constantly strive to expand their current limitations by experimenting and taking risks. An artist should always be a student, keeping that early, inner creative spirit of exploration alive and functioning. To do otherwise is to settle into a life of repetition and an aesthetic and technical niche, which soon takes the joy out of creating. Locked into such a repetitious cycle, an artist feels like a human factory, a robotic art machine. This might be financially rewarding and safe, but mental and spiritual burnout will eventually come to many who follow this path.

The difficulty in remaining a lifetime student who takes conceptual, aesthetic, and technical leaps forward is that this requires an unending supply of courage and fortitude. If an artist has developed a signature style that becomes the latest rage or results in guaranteed sales, an interruption in production of this particular work will upset gallery owners who sell this art and collectors who buy it. And change for its own sake is not always for the better, as the newer work is not always particularly good. Some new series will appear and disappear quickly, simply because the work might fail, aesthetically as well as commercially (although one does not necessarily follow the other in the art market, where aesthetically questionable art can often be successfully marketed).

Despite these potential dangers, changes in direction are the lifeblood of creativity, for they feed the insatiable curiosity of the passionate artist. And can one truly be an artist without passion? Call me old-fashioned, sentimental even, but I think passion is the quintessential element, the very core, of every true artist. To be passionate is also to be vulnerable - in life, in love, and in art-making.

And to be vulnerable is to open oneself to occasional encounters with doubt and fear. Most artists, myself included, have experienced sleepless, sweaty nights prior to a major deadline that suddenly seems to be looming too close, doubting our ability to finish the work on time and with the quality we envision. The machinery in our brain begins humming in overdrive, and we find that the shutoff switch is inoperable. Even in the conscious moments of our waking existence, our fear in a new work or series can be so great that it can stymie our ability to embark on new journeys. Visual artists have their own version of writer's block. Many times I have procrastinated beginning a new body of work or an individual piece because I was terrified that it was beyond my current abilities to produce, terrified of the possibility of failure.

Following my undergraduate studies, I was accepted into a graduate program in art at the University of California/Davis. The ceramics department was headed by the great Bob Arneson. I was drawn to his powerful works in narrative sculpture after seeing one of his seminal pieces, "Typewriter" ^965), at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. I plunged into my work during the heyday of Funk Art, which dominated the ceramic arts on the West Coast in the late r96os and throughout much of the 1970s. One-liner titles and a loose, gestural approach to the clay were "in," and tight craftsmanship and attention to detail were "out." My work was criticized as being "too small, too tight, and too precious." I was clearly not in step with my surroundings and tried desperately to conform and be a Funk Artist. This was to be the most unhappy and unfulfilling chapter in my life as an artist, and I soon returned to the work I strongly believed in.

Arneson set a great example to those of us lucky enough to be his students. He was a great mentor to young artists as he labored alongside of us, infecting us with his passion for art and allowing us to observe a real artist at work. His work included a significant number of failures, but also an inordinately large number of truly inspired masterpieces. He was never afraid to push an idea to the very edge, and I witnessed him destroying several pieces mid-creation because he realized that they weren't working. Bob was an example of the artist who would try damn near anything that piqued his imagination.

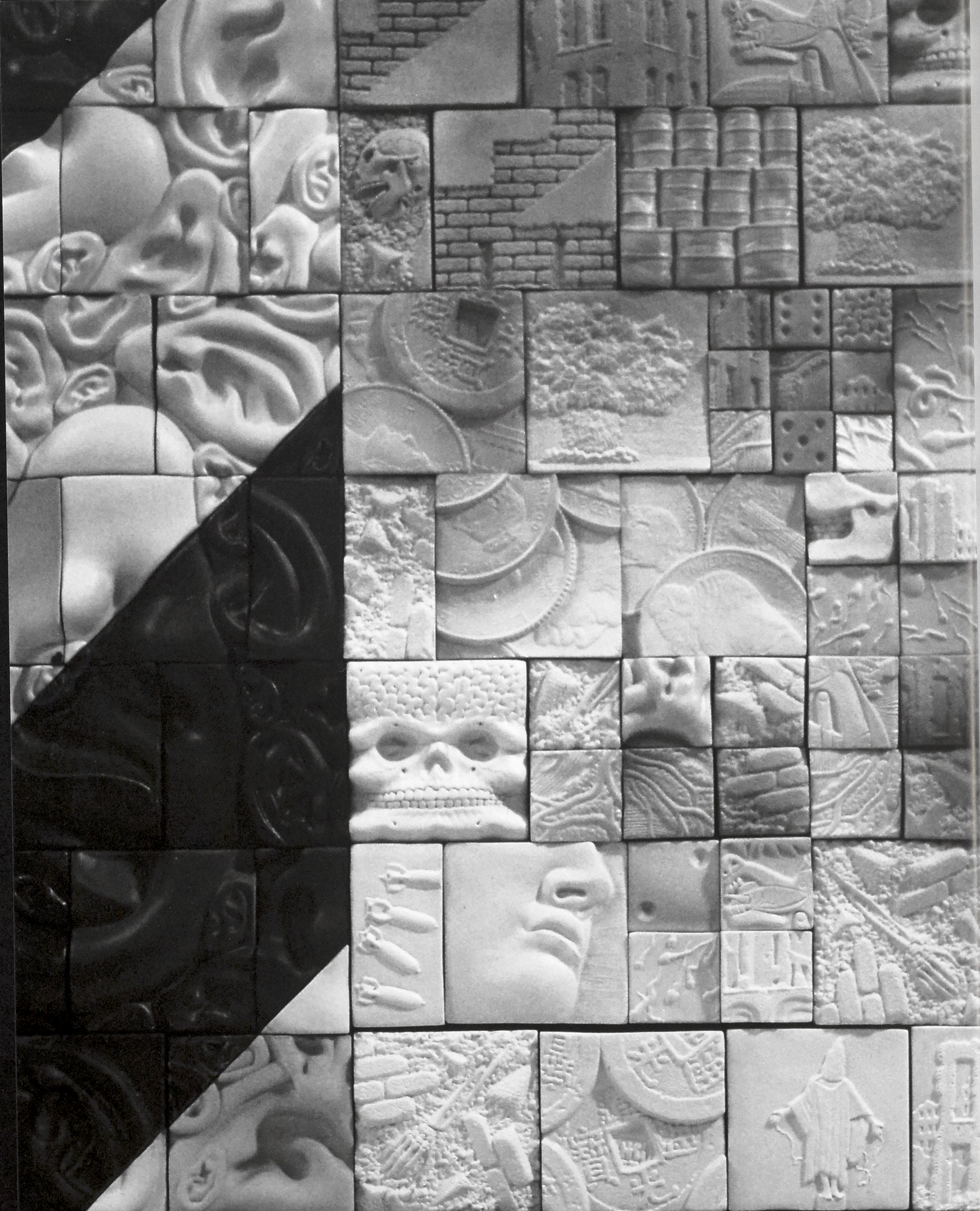

He followed as many directions as his time allowed and inspired his students to follow this essential risk-taking approach to art. The growth of his art throughout his life is a testament to his courageous approach. In fact, among the most powerful (and excruciating) works in clay that I have ever witnessed are Bob's "Chemo I" and "Chemo II," both made during the final months of his life. Emerging from U.C./Davis with an MFA in hand, I began my life as a professional artist by exploring increasingly miniature scales and the carving of smaller and smaller details. I tackled new materials and carving techniques, most of them self-taught, and switched from low-fire white clay to high-fire porcelain, which behaved in quite a different manner.

The porcelain human and cattle skulls that emerged from 1978 to 1981 for my "Endangered Species Series" were excruciatingly stressful to create. With each new skull I would try to improve upon my earlier efforts, achieving more realism

and anatomical accuracy, until I was spending about an hour and a half on each individual tooth. Working on a fragile little chunk of white mud for as long as sixty hours was also a great challenge. If nothing else, I was certainly persistent.

Working alone in my one-car garage studio behind my rented home in Davis (away from academia and faculty and graduate student peer pressures) allowed me to reconsider those early criticisms about being too small, too tight, and too precious, and to reinterpret them in a different light. This shop-worn phrase now seemed a compliment, an affirmation that my art was somehow different. I recognized that the criticisms I received during my graduate studies were merely fleeting fashion statements of a particular moment (although too many of these dicta persist to this day). And I began to see that maybe my art wasn't small enough tight enough, or precious enough to satisfy my own convictions and passions. Again, I believe an artist must first follow his or her passions and avoid being overly influenced by the verbiage emanating from many self-appointed experts. In the arts, as in everything else, when we are all thinking alike, nobody is really thinking.

The arts are at their best when true revolutionaries and rebels are leading the way with groundbreaking work that is conceptually, aesthetically, and technically strong. (A side note: It is important to remember that in art as in politics, a revolution for one generation can easily become a straitjacket for the next. True revolution is not a fait accompli; it is an ongoing process. All tradition initially began as innovation, and to complete the cycle, all innovation eventually becomes tradition. Tradition and innovation are the yin and yang - the two opposing sides - of the same coin, and both deserve equal respect.)

As a young artist, I also learned that what I could accomplish with a modicum of intelligence and an overabundance of obsessive-compulsive behavior was amazing. After all, we are all wired differently. I came to accept my wiring and to work within my capabilities and idiosyncrasies to pursue my particular art. Artists shouldn't hide their obsessions; rather, they should celebrate them! Prior to beginning difficult and personally challenging new work-pieces with

an outcome I could not guarantee - I have often experienced long periods of inactivity and procrastination. When in the midst of attempts to go beyond my current limitations, I would put off starting a new piece for days, even weeks. During the miniature-skull period of my "Endangered Species Series," for example, I would go into the studio in the morning, fully intending to start carving clay that day. My tools would be laid out on my work counter, the porcelain would be ready (the entire cubic inch of it!), and my sketches and skull models would be in position for observation. Everything would be ready to go - everything except me. I would find whatever excuse I could to avoid beginning the actual work. The plaster area would be cleaned, those shelves I had been meaning to construct would be built, or it was such a nice day I would simply have to close up the studio and take the kids to the beach. I could find a million excuses for not beginning a piece that I desperately wanted to create. Fear of failure was the simple reason, the sole stumbling block.

This syndrome has plagued me my entire career. I still suffer from it. But I now recognize that if an artist never felt this fear, it would probably be an indication that he or she was not pushing to explore new territory or allowing for possible discoveries. To turn FDR's famous quote inside out, "We have nothing to fear but the lack of fear itself."

Similarly, the lack of occasional outright failure in a finished artwork (or one abandoned in progress) is an indication that no new risks are being undertaken. And sometimes an artist can learn more from a failed work than from a successful one. The self-critic that is a necessary part of an artist's psyche should generate an internal dialogue, with questions that require frank, honest answers, if an artist is to benefit from these failures. When analyzing finished work, whether the piece is successful or not, I begin by asking, "What works, what doesn't work, what went wrong?" Then I contemplate, "If I were to attempt this piece again, what would I change?" I take notes and draw quick sketches. This critical analysis from the artist's own point of view is imperative in the evolution of an artist's work, for it becomes the groundwork for the next phase of creation. When properly evaluated, failure can often lead to greater success in the upcoming work. When exercising this self-critical eye, I try to be as objective as possible, leaving my ego behind. It's easier to be honest when only oneself is involved: you can't really fool yourself. As Terry Allen croons on his cut My Amigo, "Yeah, 'cause I know/ my ego ain't my amigo anymore..."

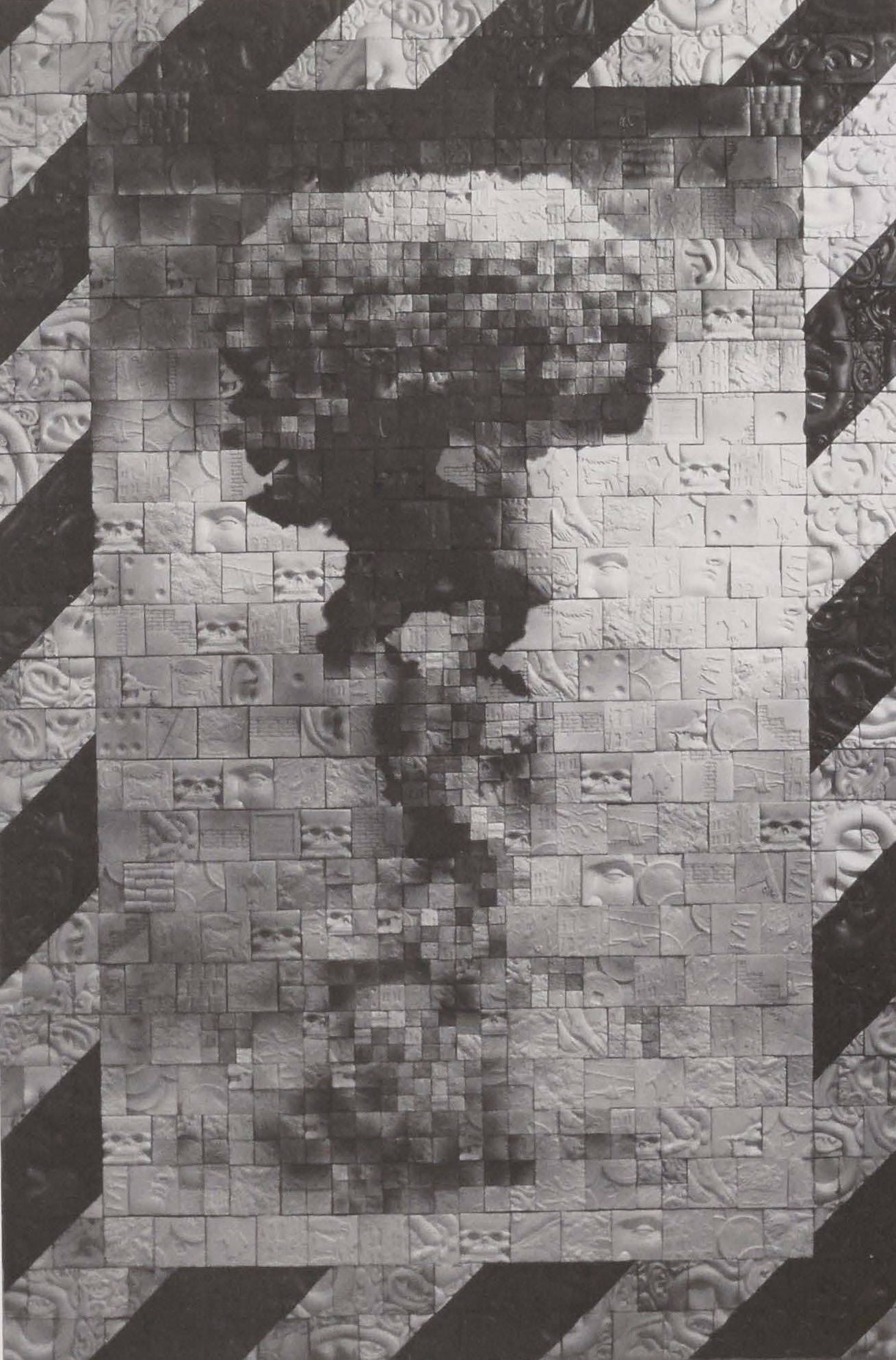

Despite my bouts with fear and procrastination, I eventually did start the miniature porcelain skulls, as well as the Yixing series of sculptural teapots, several larger stoneware installations, and my large-scale tile murals of the past dozen years. Each of these new series began with at least a bit of trepidation. After repeating this cycle for most of my life as an artist, I now recognize that this is simply my way of working. It can drive Phoebe, my marriage partner, to tears, and my gallery directors to frustration and madness, but it is the way I operate.

And along the way, 1 have learned an invaluable lesson about art-making. Within the span of an artist's life, there will be a very limited number of peak pieces, and a few masterpieces, perhaps. Looking back on the pieces I consider to be the peak works of my career, I notice that they all have one thing in common: each was begun with much procrastination and a fear that it might fail miserably

The conclusion? Fear is an indication that something great might be about to happen. Embrace it.