Even the Shampoo Was Nice

I was sitting in Eric Botbyl’s truck in the Freddy’s parking lot on one of the last few days of a short-term residency at Companion Gallery in Humboldt, Tennessee. I was eating a cheeseburger when he asked me if I would change anything about the experience at the residency to make it better for the next resident artist. The only reply I could think of was, “No, I think even the shampoo was nice.” He laughed and asked if that was the first thing I would’ve told people if the free shampoo bottle in the Gallery’s shower had been bad. In my opinion, my answer said it all, but I now realize it would take anyone else a few background stories to understand what I meant.

A few days before the residency, I was sitting in my sister’s car while we ate a bowl from Chipotle with brown rice, pinto beans, chicken, queso, sour cream, and guac. I turned around and asked her, “This is the American dream isn’t it?”

“What do you mean?” she asked.

“Do you remember back in Mexico, when going to McDonalds was a luxury that only happened on our birthday?”

“Yeah…we’ve come so far, I guess. I hadn’t really thought about that in a while.”

We were both the first generation to go to college, and the first generation to have some freedom in picking how we’d try to make a living. Our parents hoped we’d become lawyers or doctors so we’d never have to worry about money. Instead, I chose a MFA in ceramics and she chose a criminal justice degree. My sister and I both agreed we were at least the first generation in the family to choose a career that made us happy. The path to financial success still feels a bit far away, but as we were eating our chicken bowls, we were remembering a time in Mexico when we were happy enough to split an egg between my mother, sister, and me. The American dream isn’t always about having a lot of money, or a large home, or a fancy car. Sometimes it’s the freedom to choose our next meal and be able to drive over and order it.

The childhood I spent in Mexico has had a great influence on my work, and also explains why some of my stories start with food. In 2020, I painted a vase honoring the textile labor of immigrants, but it was mostly to honor the work my mother did in Mexico while we waited for her to get her green card. She sewed clothes, repaired and tailored clothes, washed clothes, and sold clothes. We would ride around in bicycles to collect payments because the people of San Miguel Octopan, Guanajuato, which is about three and a half hours northwest of Mexico City, could not afford to make full payments. The vase is painted with thousands of small underglaze dots as a reflection of the thousands of stitches my mother made to provide a decent meal for my sister and me. Some days it seemed like we wouldn’t have anything to eat, and then a cousin or neighbor would bring a shirt or a dress to repair. Those days made us appreciate the smallest acts of kindness.

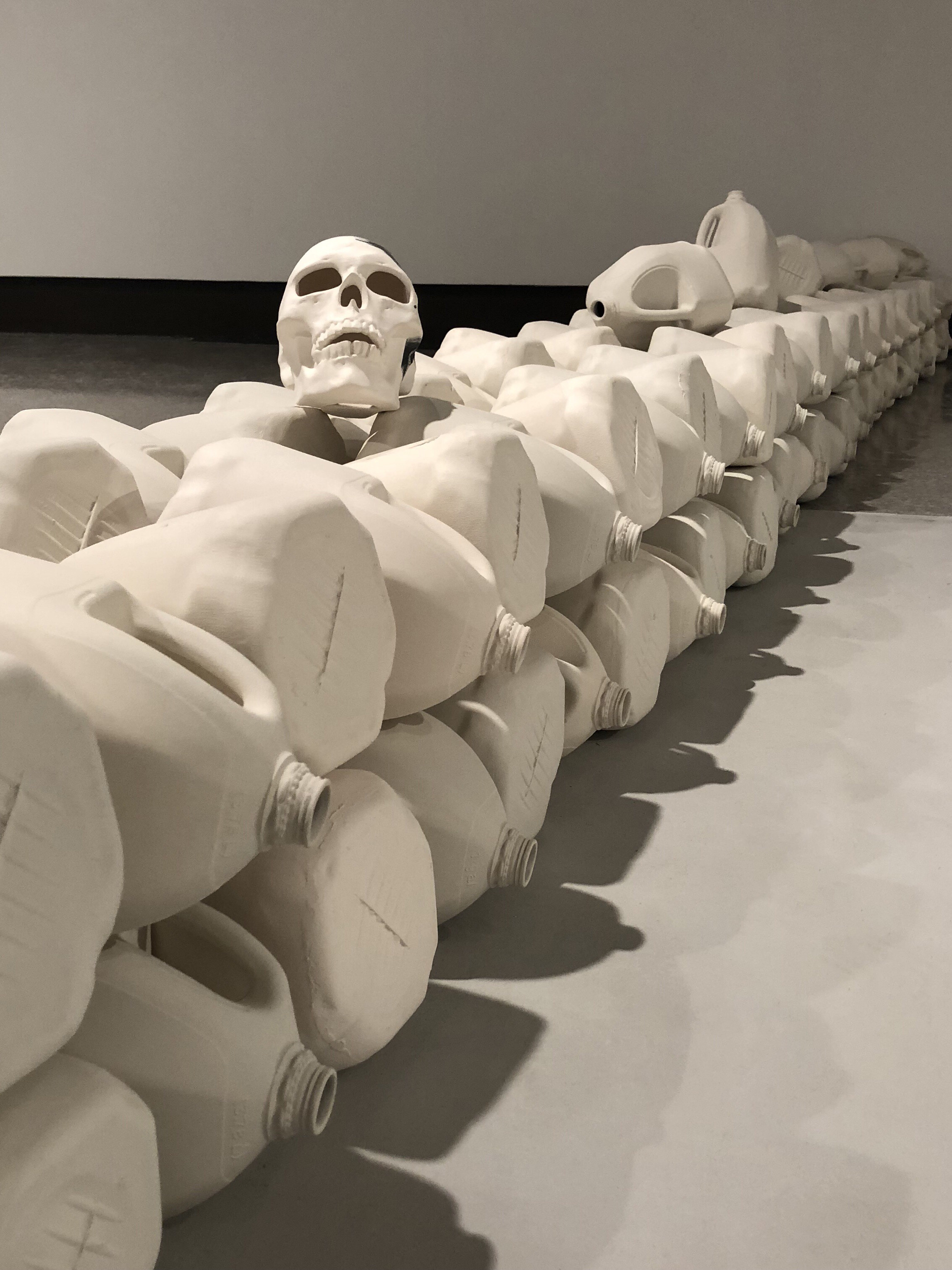

While we lived in Mexico, my father crossed the border to try and send money back to us. Most of the time, he only made enough to cover his own rent and bills. The earliest attempt that I remember was in the year 1999. Before he could reach the border, the gasoline containers on the back of the truck he got a ride in caught on fire from the desert heat. The guys inside the truck thought they had been lit on purpose and started shooting at the men on the truck bed. In the chaos of the fire and the shooting, my father’s feet got burned. He escaped and walked back to us. I can only remember bloody feet hanging from my mother’s bed for a while. For my MFA thesis show, I slip-cast two-hundrend-sixty-three water jugs, one for each of the undocumented immigrant deaths on the US side of the border in the year 1999. I did my best to honor the immigrants who gave their lives for a chance to provide for their families that year. I couldn’t help feeling happy though – that my dad wasn’t one of those water jugs.

In my family, clay has not always been associated with the hope and cultural heritage of Mexican immigrants. It has been associated with the struggles of the immigrant and, because of their childhoods, my parents initially could only see clay as a symbol of poverty. When my mother was still a child, my grandparents lived in a humble adobe brick home in San Miguel Octopan. The adobe bricks, a mixture of clay, sand, and silt, were not able to stop the rain from leaking down on my mother and her seven siblings. To make sure his children didn’t get wet when it rained, my grandpa would set up some poles and a sheet of plastic over the one bed the kids had to share. When it was time for lunch, they’d fight over what brick to sit on because they didn’t have chairs. Eventually, my grandpa grew tired of their living conditions and decided to cross the border into the United States. With the money he sent, the adobe bricks were slowly replaced with fired bricks and concrete. My grandparents and their children eventually crossed the border and, with the exception of my mother, became legal residents under President Reagan. By then, the fired bricks that had been their chairs had been replaced with my grandma’s collection of over forty fold-out chairs and armchairs.

Clay was also present in my father’s childhood, leaving a mark on his clothes and self-esteem. Expected to work in the fields at a young age, the grimy appearance of his clothes was unavoidable. He was left-handed and attending a Catholic school at a time when being left-handed was considered a sign of the devil. The nuns running the school made him feel like a dirty child of Satan. With his left hand tied behind his back, he would stare at the exams placed on his desk, and with a shaky right hand begin what he knew would end as illegible failure. He endured hunger and emotional abuse until he grew up and the opportunity of the American dream presented itself. He found my mom, and I was born a year after they got married, followed by my sister three years later. After working on a farm and every construction job imaginable, there were days he would come home covered in mud. It was obvious he could still imagine what those nuns would have said about his appearance.

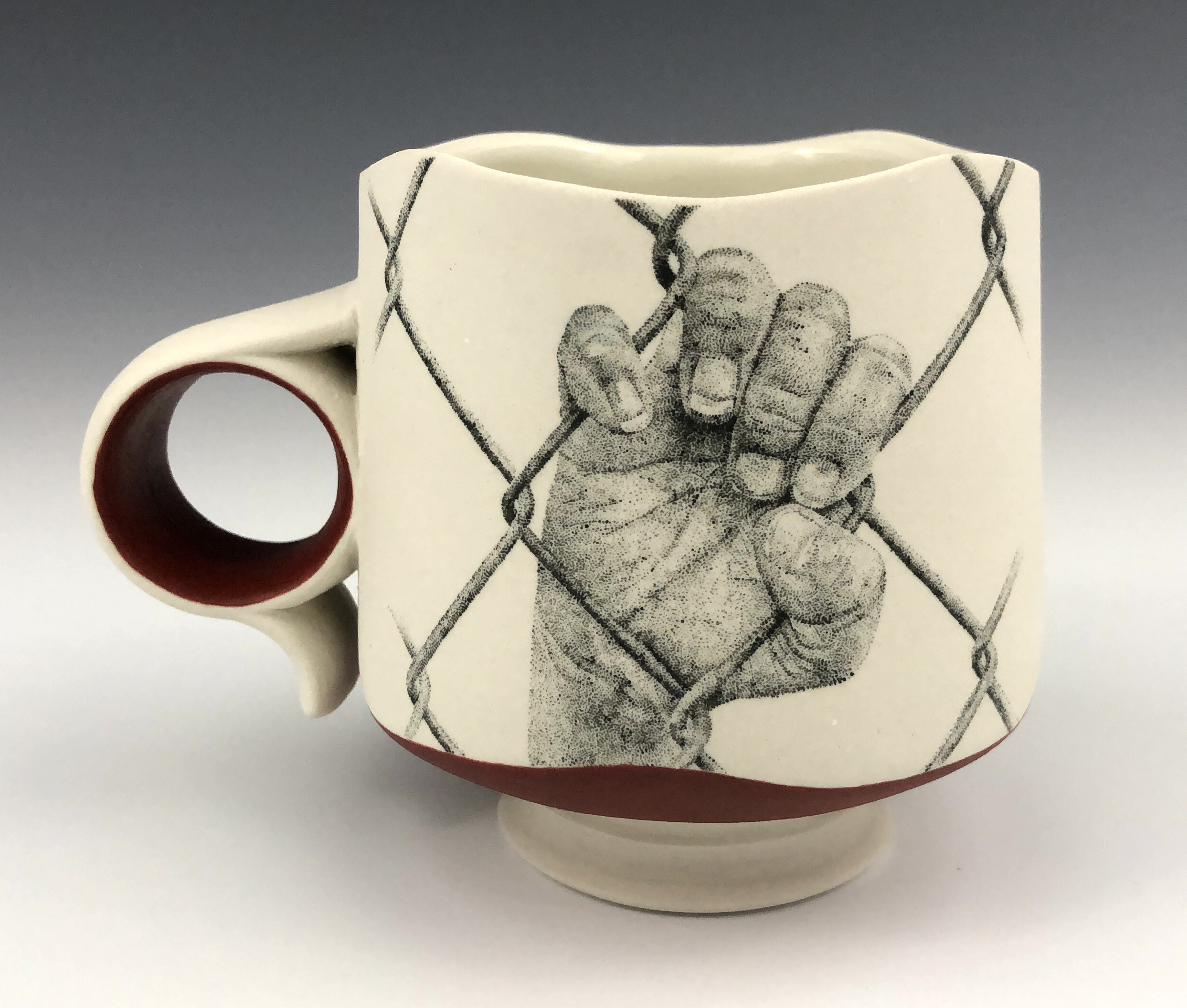

It was easy enough to convince my parents I wanted to be an artist after they saw my oil paintings. However, when I told my parents that I wanted to be a ceramic artist, they did not approve. My mother’s reply was, “Why? So that you can sell mugs for ten, twenty dollars?”

The answer I wasn’t ready to give them is that to take such a mundane and humble material like clay, a material that had hurt my father, and turn it into something of value feels like a beautiful metaphor for what they did with their lives and their labor. I could see their resilience and will to provide a decent meal for my sister and me reflected in the medium of clay. They had lived with an underdog mentality of making the most out of the least, and I was doing the same with clay. By the time I had figured out a better answer to my mom’s question, I had sold a cup for $350 and she had found her comment amusing.

The last few days before my MFA thesis show, my dad was helping me slip-cast two-hundred-sixty-three water jugs. There were several spills of slip at first and by lunch time his pants were usually smeared with clay. On the way to get food I asked him if he was embarrassed of going out to eat with his pants covered in clay. His reply was, “What? It’s evidence of hard work.” I don’t think he realized that his view of clay had gradually changed. By the time I graduated from grad school at the University of North Texas, my mother had accepted clay as a medium to honor the dignity of immigrant labor. My father had accepted clay and messy pants as evidence of labor. He speaks proudly of building fences with care and a love for precision and detail.

My family’s story has been one of resilience and hope, of making the most from the least, and of appreciating the smallest of things. When I left graduate school, and found myself without a kiln or studio space, I did not lose hope. It was a chance to embrace once again an underdog mentality, despite material and professional limitations. I built some fences with my dad, saved up for a small test kiln, and took over my parents’ coffee table. This old wooden coffee table has been my studio space for the last year. I’ve used it for mold-making, slip-casting, painting, as a photo documentation booth, a lunch table, and currently as an article typing table. The pots made on that table have helped me raise the garage floor four inches, and now water doesn’t leak inside when it rains. The moldy garage walls have been replaced. I will soon have a larger kiln.

By the time I went to Companion Gallery for a short-term residency, I saw my experience there as a glimpse of what I could accomplish with the freedom of time, a large enough kiln, a larger workspace, a complete Amaco underglaze palette, and a continuous supply of sweet tea. I love my coffee table, but it was nice to work without the constant feeling of going one step back in order to go two steps forward. I learned how to make decal work, and as a result, a more affordable edition of pieces. I also added a variety of colors to the bottoms of my mugs that I would not have been able to afford otherwise. Besides inspiring, the resident artists there were friendly, talented, kind, and humble. Mrs. Botbyl gave me more food and snacks than I could finish in my time there. At the end of my workday, Eric and I would spend some time telling each other stories. The laughs were good for my mental health.

By the time I went to Companion Gallery for a short-term residency, I saw my experience there as a glimpse of what I could accomplish with the freedom of time, a large enough kiln, a larger workspace, a complete Amaco underglaze palette, and a continuous supply of sweet tea. I love my coffee table, but it was nice to work without the constant feeling of going one step back in order to go two steps forward. I learned how to make decal work, and as a result, a more affordable edition of pieces. I also added a variety of colors to the bottoms of my mugs that I would not have been able to afford otherwise. Besides inspiring, the resident artists there were friendly, talented, kind, and humble. Mrs. Botbyl gave me more food and snacks than I could finish in my time there. At the end of my workday, Eric and I would spend some time telling each other stories. The laughs were good for my mental health.

Halfway through the residency, I was able to tell the story behind my new pitcher form during a class demo. The form was made from a mold of a detergent bottle. I had shaped the spout using an oil-based clay that I stuck and blended over the plastic. My pitchers are my most recent attempt to honor my mother, and the story made a lady tear up. I think one of clay’s most noble functions could be in helping humanize immigrants. This lady perhaps just saw a son’s love for his mother instead of the son of “aliens.” I think that moment is part of what my work has been about.

Halfway through the residency, I was able to tell the story behind my new pitcher form during a class demo. The form was made from a mold of a detergent bottle. I had shaped the spout using an oil-based clay that I stuck and blended over the plastic. My pitchers are my most recent attempt to honor my mother, and the story made a lady tear up. I think one of clay’s most noble functions could be in helping humanize immigrants. This lady perhaps just saw a son’s love for his mother instead of the son of “aliens.” I think that moment is part of what my work has been about.

At the end of the residency, I sat down looking at more than forty of my ceramic pieces on a table space twelve times the size of my coffee table. Before my parents became legal residents in 2014, the idea that I could be invited somewhere and then given food and drinks while I made things with clay would have been impossible to imagine. Before that, it felt like we were always one speeding ticket away from deportation. I lived in fear and did my best to blend in, keep my head down, and not share my stories or family history. The work I made at Companion Gallery is part of my first solo show called Immigrant Narratives, a body of work based on Mexican labor and the plight, struggle, hope, and heritage of Mexican immigrants. Accustomed to making do without or working with limited materials, it may come as no surprise that I found the Companion Gallery short-term residency full of an excess of kindness, space, opportunity, food, and friendship. Every obstacle had been removed between myself and artistic creation to the point that even when I realized I had forgotten my shampoo bottle at home, the one that was already provided in the gallery’s shower ended up becoming one of my favorites.