Darwinian Ghosts

As a contemporary potter, I am a scavenger. I sift through the detritus of thousands of years of a ceramic medium searching for nutriment.

In chasing the shapes I make, I start within a tradition. As an apprentice I inherited an archetypal range of shapes, easily recognized as useful by the common eye. These shapes are the strongest of the strong, having carried their merits from ages past, across the generations, to the fertile shore of my present-day wheel head.

My pots, while traditional, are also dynamic because they cannot help but contain what I bring to tradition. To these old and vigorous shapes I bring my family's creative spirit: my father's, aunt's, uncles' pots, music, weaving, gardening. Every day I spend at the wheel I bring this amalgam to the crucible of tradition.

“He Who Has No Tribe…”

I worked for Outward Bound during the summer of 2003, leading a wilderness canoe expedition through an area where the Ojibwa tribe used to live. At a workshop on Restorative Justice, OB staff looked at how to approach disciplinary action in a wilderness setting with youth at risk. One goal of Outward Bound and Restorative Justice is to ensure that a participant is aware of the impact his behavior has on expedition members. Mention was made of the translation of the closest approximation the Ojibwa language has to the word 'criminal': "one who acts as though he has no tribe."

During a Christmas visit to my parentsin- law's home in Maryland, we went to see the "Asian Jars" show at the Freer Gallery in Washington, D.C. The pots made me weak in the knees, as did the excitement of sharing artifacts so closely tied to what I do for a living. For me, the most touching part of the explanatory text that accompanied the exhibit was the idea that mere shipping containers became family heirlooms, even marriage dowries. In this country we attribute value to antique objects that are beautiful, yet a large part of the antiques market also places value on dusty Coca-Cola signs. I understand the appeal of Coca-Cola, but I cringe at the notion of a caffeinated and carbonated beverage company with a brutal drive for profit as an American icon. There must be a different icon for our tribal identity. What are the objects that define our culture? What are our tribal heirloom jars?

Carl’s Pot

A dear friend, Carl Curtis, died last November, and his family asked me to make an urn for his ashes. Carl made some pots and led an admirable life. I knew that I wanted to try to make his urn in the spirit in which he lived.

More important to me than the outward aesthetic considerations was that I wanted to be actively honoring Carl while the pot was on my wheel. It was a wonderful way to work. I paid more attention to my breathing and the sounds around me. I paid attention to how my muscles felt the choreography of the shape progressing. I took my time, even though it was a hectic part of my production cycle. It was a remarkable moment in my shop and I wish I could make pots for Carl every day.

Carl's pot is an untrimmed, unsigned, full-bellied jar, the throwing of which fully exploited the plasticity of my aged and carefully-blended clay body. Its purpose is undeniably utilitarian. The form is inspired by a shape I learned during my apprenticeship called the monkey jar; the narrow opening at the top allows passage of the empty hand, but the monkey who does not let go of the contents stumps about with a jar stuck on its arm. I realize only now that we must do this with Carl's remains; once they are in the jar we must let go of Carl's physical presence in our lives. The shape of the pot has deeper roots in Chinese four-handled shipping jars. It's fired with hemlock timbered in the immediate area, and ash and maple thinned from my farm. The glaze was formulated from clay that Carl's son Ira and I dug on the Curtis farm, along with mixed and unwashed hardwood ashes from my aunt and uncle's woodstove. Three generations of Curtises live and work on their farm, firing their sap condenser with wood from their land in the production of organic maple syrups and sugars. Carl's pot will be buried there.

What I've realized since making Carl's pot is that every day I'm in my shop I am haunted by witnesses to my creative process. These witnesses, whether real or imagined, support me in doing my work well when my energy is flagging. When tempted to cut a corner I imagine having to send the pot to Skudlarek, my friend and mentor during my three-year apprenticeship; Thiedeman, my college advisor and mentor, or one of the Unknown that Yanagi wrote of. More immediately, I imagine what my wife Mariana will think when she gets home from work. Specifically, I imagine Carl's spirit witnessing the creative process by which a container for his ashes was born. In the moments of breathing life and vitality into these objects I am open to another's spirit, to a timeless relationship with the material, and to the innovation that comes because no hands are shaped as mine are, no eyes see through the same lenses and no spirit is born of the same chromosomal and cultural community. I am individual without trying. The difficult work is harmonizing: singing my different note but also sounding beauty in concert with my tribe. My witnesses - near, far, long-dead or breathing, real or imagined - are my tribe. May I work as though I belong.

My Father’s Jars

My father's work is that of extrapolation. As his son, wanting to see into his soul to better understand my own, I too extrapolate. While there are precious conversations and shared moments that allow me a glimpse of who my father is, I cannot simply ask to look at the parish register that his spirit has kept, marking the birth and growth of his soul.

My father's first, brief career course was pottery. His progress in that regard slowed down after the loss of his largest body of work, made during a Penland School of Crafts course, in a house fire. It slowed further as he and my mother decided to shape their careers around a family. Few of my father's pots remain. While I have cajoled him into making some pots in recent years, I have only traces of his first career path.

I have one of a run of storage jars that he made at Penland. To my knowledge, it's one of two that remain. I didn't think twice about it growing up; it was just another piece of kitchen décor until I had been turning pots myself for a couple of years. Then I developed a ravenous appetite for different ways of making pots, and this jar was simply one of the morsels I consumed with my eyes, hand, and heart in the exploration of a new medium, a new language, a new world. I made jars in the likeness of this one while I was still in college, but they were always simply a response to the shape of his jars, an effort to improve this heirloom jar through my own innovation, my own self-conscious desire to be different. As I grow into adult shoes, I fear my similarities to my father less. Included in the kiln's yield from my second firing was a run of jars that I made, trying my best to emulate my father's jar. I didn't realize it until I had the clay on the wheel, but the intimacy of shaping these pots stole my breath. It was a moment in the shop where my awareness focused so dramatically that I could hear the silence; my own thoughts and pulse seemed deafening. My whole being held its breath to see what coursed through my shaking hands. It was not a feeling of competition, though I did face the "what if it's not as good as my dad's" issue. There was distinct weight to the knowledge that my father's hands had followed a similar path, if only for one run of jars.

As I turned those jars, the essence of my father's soul did not come pouring forth, laid out clearly for me to see. There were no fireworks or sparks of energy coming from my fingertips as I stepped onto the well-trodden path of my folk-potter heroes. There was, however, peace in the knowledge that my father followed and continues to follow his dreams and passions. There was also peace that came from the knowledge that I am following mine. The intimacy that I felt in the air was one of a dream momentarily shared.

I have vivid memories of my first experience with clay. My mom had just read a version of Genesis in a children's bible stories collection. It seemed simple enough and within minutes I was excavating the mud from our front yard and smearing it on the best substitute for Adam's ribs I could find: a milk crate. I don't remember if I finished that particular project. I do remember my certitude of being able to shape a vessel that would contain a soul.

I do not attempt to make heirloom jars. I simply do what I love.

I choose my shapes from my tradition; I share, through this extrapolation, in the prolific post-Cardew aesthetic. The pots I make fall within this tradition, yet I also bring to it my family's rich history of artistic endeavor. To check cones, I wear welder's goggles that my uncle bought while studying ceramics at Alfred in the early sixties. I see all of what I do through lenses colored by the culture of my family.

My jars contain my soul. My jars are my entry in the parish register, my heirloom seed for future apprentices and my children.

My Grandpa Dan

My grandpa Dan played his mouth harp for the last time at my June wedding in 2002. Two weeks after my wedding, he had a stroke from which he has recovered only the most minimal ability to speak and has not played music since. Live mouth-harp music will forever evoke images from my wedding.

Dan and Grandma Rosalie lived on this farm where I now live for over fifteen years. I stayed at their house every summer and Christmas vacation as far back as I can remember. I roamed in their woods with the sense of aimless purpose seen only in children: I built my first house of sticks and whiled away hours "at work" in those woods. I've since come to the other end of them, where my uncle and I built my house and workshop. I still head off there to thin the hardwoods for kiln fuel, and to dig clay.

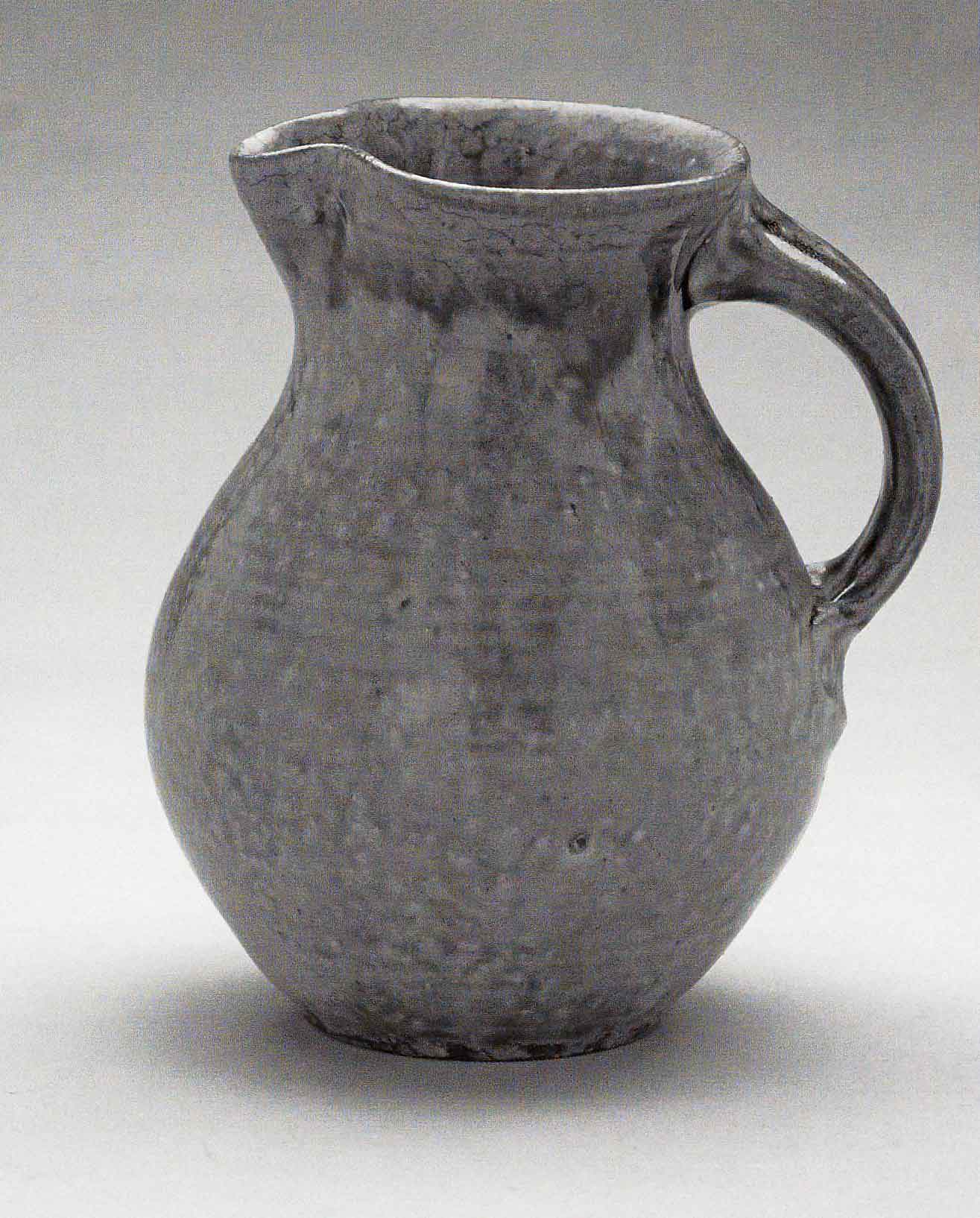

Recently I visited Dan. I brought a pitcher - a six-pound North Devon style with an unglazed exterior - to leave with him. Dan still understands all that's said to him as well as he always did, though at present, and with great effort, he can utter only one or two words. He held my pitcher in both hands and uttered one word:

"Jug."

Is there a higher function than bringing quiet beauty to a ritual object that holds the first caress of the lips, the first utensil held by the hand each morning? My mugs are incomplete until the moment of that first hot coffee kiss. The intimacy of hundreds of such moments is lost when a work is distanced by an assumption that the ideas involved in art are beyond common understanding.

On the way to see Dan I stopped at a gas station to fill up a mug of mine with coffee. An older woman who rang me up commented, 'That's a nice mug. Did you make that? You did? That's great. It's got that old-fashioned look to it." My mug is the still recognizable "old mug" archetype.

Straightforward, utilitarian shapes are evocative icons. In working from these archetypes I draw from a cultural taproot that affords me instant connection with a collective eye still sensitive to ancient shapes. I treasure the defining characteristic of my work that rendered it accessible to my grandpa, and to a still-significant portion of our culture.

Though struggling with Parkinson's, the ensuing fogginess imparted by medication, and the limitations imposed on him by a stroke, Dan was still able to recognize the archetype my pitcher invoked, and named the shape and its origin. The American "jug" is the English "bottle"; "jug" in England refers to our pitcher. Whether or not Dan knew of my piece's roots in North Devon, he clearly chose the English derivation of the archetypal shape's name.

Politics

My culture is inextricably woven into a capitalist economy. What I do with my money is as much a political statement as how I vote. The business I run, "retail pottery sales," is based on a set of bottom lines that extends beyond the traditional overarching goal of financial profit. Consequently, it is my aim to be politically expressive with the work I do.

First, I acknowledge that I am not entirely removed from this economy. I depend on petroleum-powered deliveries of clay, wood, and building materials. My shop is heated with oil (though it is on a super-insulated radiant slab and as such is dramatically more efficient than many shops I've seen). Further, my pots are luxury items despite their being priced at the reasonable end of market value. I have limited my audience by definition, much the same way that organic meats, grains, and produce are aimed at a niche market.

In looking at the people I do reach, I imagine what they see:

I make pots for myself first. I do my work because I love doing it. I even love the janitorial end of it: washing the floor, cleaning out my kiln after a firing, scrubbing kiln furniture, mixing and pugging clay. I do not do my work because it makes me lots of money.

I make pots for my customers. If a pot is flawed or rendered less usable by some miscalculation, I charge less for it. On the whole, I keep my prices low enough that my customers feel comfortable using the pots without having an excessive fear of chipping them. I am able to do this in large part because of my training. I can make high-quality work in large volume; my kiln holds up to 1,500 pieces per firing. As a result I'm able to make a decent living and price my work to use. My customers are part of my tribe.

I sell regionally, and eighty percent of my sales involve a face-to-face interaction with the company CEO, line worker and middle management at the factory! My work is relationship- based, in that I make for use and my customers use. Yet the relationship extends further in that my potential customer can see the physical manifestation of my dreams and ambitions. Their tour of my kiln, the dust under their feet in my workshop, the smell of curing hemlock, and the fall colors on my farm are a significant portion of what they buy; they take home a coffee mug already full of the conversation, nori rolls, and quiet farm backdrop that I've shared with them during their visit. I have an unusually good customer-relations department.

Finally, my work pays the bills, but my work is not fully my work unless it has achieved all of the aforementioned bottom lines first. As a business model with a skewed set of bottom lines, the mission statement I share with my investors is one of hope, faith, and vigor. My work is quixotic and Walter Mittyesque in the face of current cultural-economic trends toward faceless, distant, and underpaid labor.

“Most Like an Arch…”

I began gathering materials for my wood-fired kiln at Stony Meadow Pottery in the final year of my apprenticeship. While there were some necessary purchases, my budget was limited and the bulk of my kiln is built from scavenged material. The lion's share of my scrounging came during a two-week work camp in southern Ohio. With the help of some good friends as well as the staff at Cedar Heights Clay Company in Oak Hill, I palletized over twenty tons of used firebricks. The bricks were salvaged from old kilns used to fire firebrick, so many of the bricks at the site had been rendered unusable by exposure to extreme temperature. For every brick I was able to stack for use in my kiln about twenty had to be discarded. All in all, we picked up close to 80,000 bricks to find the 4,000 I needed to build this kiln. Those two weeks are memorable as some of the hardest work weeks of my life.

Before my workshop was finished enough to move into, I turned pots in the old barn here on the farm. Making pots in there that first summer was as much an exercise in archaeology as it was an artistic endeavor. Paulus Berensohn and MC Richards made pots here before I was born. Their tools and old glaze materials are everywhere. Every time I measure a lid I see "MC" written on the calipers. My dad, Uncle Larry, Aunt Laurie and others shared a makeshift studio in that bam with Paulus and MC in the early seventies. Bricks salvaged from their kilns are in the floor and chimney of my kiln. Some of MC's ashes were introduced into my kiln at top temperature during my first firing. Though I couldn't discern a conclusive difference in the surface, I know that minerals that once defined her physical self were united in an intimate and fiery dance with the pots in my first firing.

The kilns I salvaged my brick from are long gone, but the bricks, now reused, continue to provide a bountiful harvest, each brick infused with the strength of a new arch. The kilns cultivated two very different crops. The brick kilns were a piston in the immense engine of earlier industrial America, providing a central building material to foundries at a time when railroad steel was essential. The industry provided jobs to working-class America; these kilns' yield was characterized by a fundamental need for consistency and often by grueling physical labor. Paulus's and MC's kilns

fired clay as the conduit in a search for poetry and spiritual grace. The nutrients from these crops also feed the seedling of my career. My work and the kiln fuse old and new into strength, through the falling together of kiln arch and the marriage of new blood into tradition.

Vision

Paulus recently shared with me a Haystack Mountain School of Crafts monograph that he wrote. He wrote in one section about a scientific study concluding that clay releases energy when struck. With my wife away pursuing graduate studies, I'm spending time in my shop at odd hours, long hours. I find myself awake at milking time, my body inexplicably energized, my hands tingling in anticipation.

There is a full moon this morning, and the meadow outside my shop window is lit brightly, but too many wee-hours cone peeps have left my night vision weak. My shop lights are all on despite the moon glow in the clear Endless Mountains air. Since my shop is still young, many of the lights are still in boxes, waiting patiently to be hung. The space is sparsely lit at present.

In a photography class in college, we squinted at photographs to examine composition without the distraction of subject matter or surface texture. I squint at the dim forms of my predecessors to determine their composition, searching for the nutritive matter, feeding, then searching again. I squint in the predawn fluorescent hum to see what my own work is made of, yearning to see the nature of my own relative worth.

In my journal from college there's a photo-copied picture of Michael Cardew taken late in his life. He is squinting at a pot to which he's taking a brush. I stepped into the tradition that I share with him full of determination that I would match the greatness of Cardew. I stepped in with trepidation, fearing that I would be unequal to follow that path. My determination drove me to work rigorously and enthusiastically, egged on by the work ethic of the Minnesota farm boy whose paces I strove to match for those three years.

I approached my work at the wheel armed with this determination, straining at the spinning pot, reaching as hard as I could to raise my shape and to stretch it as far as Skud's demo pot. Many lumps turned back into lumps, their heels clipped by the hurdles of over-thinning, pot-wall torque, inconsistent clay, indecision about detail. I glared with scrunched eyes at the point where my shaping rib made contact with my piece, daring it to wobble, slump or plant its bottom-heavy countenance on the board with its rim lower than the previous one. A hard-earned lesson learned toward the end of my tenure that I relearn each time I approach my wheel: keep the eyes wide open, the better to see the whole of the shape and the lines that I want my work to settle into. Stages of my shapes require work of my muscles. Clay releases energy, however, and many stages simply require that I be there, that I breathe, behold, and honor what I value. The time I spend at my wheel, having re-learned this lesson, is time when the work does itself.

It's getting light in the shop now and I see the parts of my pots - six-pound, North Devon-style pitchers, light and airy yet pregnant and full - that were previously shrouded and shadowy. The clay settles itself along the ancient lines more easily in the dawning day as the squint lines around my eyes fade with the stars. I breathe deeply, content with the shape I am taking. I am rising toward the fulfillment that a long life in clay has to offer. My father's pottery career, Cardew’s and Skudlarek's legacies, and MC's and Carl's lives remain obfuscated, dreamlike and amnesiac. Yet in walking through the dark I have been led here - awake, nourished, and energized by spinning lift.