Crawling Through Mud: Avant-garde Ceramics in Postwar Japan

INTRODUCTION

Certain trends in Japanese ceramics since 1945 have become quite familiar to American audiences. Books, exhibitions, and influential advocates have introduced the "folk craft" (mingez) potters and the potters named "Living National Treasures" by the Japanese government for their work in reinventing and perpetuating modes of historical Japanese ceramics. Both these essentially conservative tendencies are embodied in Hamada Shoji (1894-1977), who visited the United States in the company of his advocate, Bernard Leach, in 1952. Hamada was a founder of the Folk Craft Movement and was designated a "Living National Treasure" in 1955.

The goal of this essay is to introduce a quite different development in postwar Japanese ceramics - an avant-garde movement that has been of profound significance to several generations of Japanese ceramic artists and their patrons. The leading figures in this movement were a group of young Kyoto potters who looked not back - to historical models or an ideal of rustic simplicity - but outward across national traditions and boundaries. Starting their careers just at the end of World War II, these artists were determined to connect their work to modes and ideas in international modernist art. Emerging from a pottery industry steeped in tradition and associated with categories of utilitarian vessels, they struggled to redefine their work as potters and to establish clay as a valid medium for abstract sculpture. In 1948 they formed a group named Sodeisha, the "Crawling through Mud Association". Their leader was Yagi Kazuo (1918-1979), who was thirty years old when Sodeisha was founded. His fellow founding member Yamada Hikaru (1924-2001) was twenty-four, and Suzuki Osamu (1926- 2001) was twenty-two. Forming groups was a common practice in postwar Japan among artists who banded together to debate ideas and hold exhibitions, although most groups were short-lived. These young men never anticipated that Sodeisha would last for half a century, disbanding only in 1998.

I will introduce the actions of the Sodeisha artists through works that you may have had a chance to see yourselves as they appeared for the first time in the United States. The works were a major component of the exhibition Isamu Noguchi and Modern Japanese Ceramics, (Arthur M Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 3 May- 7 September, 2003; Japan Society Gallery, New York, 9 October 2003 - 11 January, 2004; Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, 7 February- 30 May 2004). The exhibition's narrative thread follows the ceramic work that Japanese-American sculptor Isamu oguchi made on three occasions in Japan, in 1931, 1950, and 1952. Noguchi's work is paired with work by nine different Japanese artists whom Noguchi knew. Because his connections within the Japanese art world were wide-ranging, the exhibition includes the work of "Living National Treasure" potters Kaneshige Toyo (1896-1967) and Arakawa Toyozo (1894-1985), and their associate Kitaoji Rosanjin (1883- 1959), who was Noguchi's host in 1952; Kawai Kanjiro (1890-1966), who is known in the United States only for his role in the Folk Craft Movement, but who responded after the war to the same international trends that inspired the Sodeisha members; the sculptor Tsuji Shindo (1910-1981); and the painter Okamoto Taro (1911-1996). All these artists belonged to Noguchi's generation. The Sodeisha artists were a generation younger, just starting their careers as Noguchi's ceramic work was exhibited in 1950 and 1952, and it was for them that Noguchi's unconventional handling of Japanese clays and glazes held the greatest excitement and provocation.

I also have another goal in making you aware of the accomplishments of the Sodeisha artists. Our society tends to view developments in modern and contemporary art as the prerogative of Euro-American culture. We assume that all significant transformations in the art world "happened first" in the United States or Europe and, thus, that manifestations of similar impulses elsewhere - particularly in Asia - are derivative. This unfortunate assumption reflects our ignorance of developments elsewhere. For example, if I ask you to think of the "ceramic avant-garde" and associate it with a time and place, chances are that Peter Voulkos (1924-2002) and others associated with the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in the late 1950s come to mind. Without question that episode, which enlarged the domain of American ceramics beyond domestic utilitarian wares to include abstract sculpture, had a tremendous impact. It was not, however, the only mid-twentieth century "ceramic avant-garde". Nor was it the first, since the Japanese movement led by Sodeisha captured public attention (even international attention) several years before comparable activities began on the West Coast.1 But timing is of little importance, since each society generates its own context for an avant-garde movement. Instead, it is fascinating to see that both the Sodeisha artists and the Otis artists were energized to work with clay in a new manner by a common source - the painting and ceramics of European artists including Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Juan Miro (1893-1983). It is startling that the two groups appear to have been completely unaware of one another.

Although it is often stated that the "Otis movement" artists were also inspired by their encounters with Japanese ceramics, I find it curious to realize that Voulkos and his colleagues embraced the very lineages of Japanese ceramic orthodoxy from which the Sodeisha artists fought to free themselves. Voulkos famously spun the potter's wheel for Hamada at the Archie Bray Foundation in 1952, and he saw the revivalist ceramics of Rosanjin (who toured the United States in 1954) and Kaneshige (who followed two years later). The manner in which Rosanjin and Kaneshige manipulated unglazed clay to recreate sixteenth-century Japanese forms - with roughly contoured shapes and scored and gouged surfaces - can be seen in Voulkos' sculpture from the mid-1950s onward, as in his "tea bowls" and his "ice buckets" derived from tea-ceremony water jars. The Sodeisha artists vigorously discredited this mode of work, accusing it of pandering to the emotional responses of a nostalgic Japanese audience. We can simply observe that what is overly familiar in one context can be startlingly fresh in another.

CONTEXT

The young Sodeisha artists who set out to transform Japanese definitions of ceramics responded to circumstances and conventions distinct to Japan. They questioned virtually all the conventions of ceramic materials, form, decoration, and function (although they never doubted the emotional power of clay as a material), and they addressed broader issues of presentation, social hierarchy, and the political role of art. Before presenting their activities, I should describe the context in which they found themselves as it relates both to the traditional Kyoto ceramic world and the circumstances peculiar to the immediate postwar environment.

The focal point for Sodeisha activities was the city of Kyoto, seat of the imperial court from the ninth through the nineteenth century, enduring home to Japanese classical culture, and center for the production, distribution, and consumption of luxury goods. Kyoto is the origin of refined artistic practices including the tea ceremony, flower arranging, and incense connoisseurship, as perpetuated by professional schools still based there. Kyoto cuisine is famed for its subtlety of taste and elegance of presentation. Kyoto natives speak in a strong dialect and use an oblique language that often means the opposite of what it seems to. Kyoto is a notoriously difficult place for outsiders to gain entry, although it is full of crafts workshops started by interlopers who managed to gain a foothold. Kyoto communities - whether neighborhoods or professional cohorts - subject their members to intense scrutiny and discipline. Nowhere is the Japanese saying "The nail that sticks up gets pounded down'' truer than in Kyoto.

The Kyoto ceramics industry arose in the late sixteenth century, when merchants began sponsoring workshops for low-temperature lead-glazed ceramics (which we know now as Raku) based on imported Chinese technology, and for glazed stoneware introduced by potters migrating from provincial kilns. Within a few decades the best Kyoto makers of glazed and enamel-decorated stoneware, such as Ninsei (active circa 1646-1677) or Kenzan (1663-1743), were known by name throughout the country. Most Kyoto ceramic products were linked to artistic and cultural activities closely associated with the city - tea bowls and water jars for the tea ceremony; vases for ikebana; and tableware for fine restaurants.

The workshops for Kyoto stoneware (and, eventually, porcelain) clustered on the hills east of the city, in neighborhoods known as Awata and Gojozaka. At the close of World War II, when the Sodeisha story begins, ceramic production was still in the hands of small, family run factories, headed by generations of masters who inherited their artistic names, and staffed by skilled specialists who also tended to pass on their skills to their sons. The interwoven economy and society of the Gojozaka community were dominated by the fifth and sixth generations of the Kiyomizu Rokubei workshop, which perpetuated Kyoto-style

decoration on stoneware and also made porcelain with Chinese-style glazes. These powerful men - entrepreneurs as much as artists - strutted proudly up and down the middle of the sloping lanes in the potters' quarter, while others kept to the side. A few independent "studio" potters, including Kawai Kanjiro and Ishiguro Munemaro (1893-1968), also operated small workshops in this area.

Most Gojozaka potters did not own their own kilns but rented space in a cooperative kiln. Specialists fired the kilns, while other businesses supplied firewood, clay bodies, and glaze materials. Even if many young men of the community began their training at home, they finished with formal instruction at the city-operated Ceramics Research Institute or one of several other technical schools. There they absorbed the essential skills of wheel-throwing and glazing and studied the models for shape, glaze, and decoration provided by historical ceramics from China, Korea, and Japan. For Kyoto potters, definitions of personal accomplishment were framed by four hundred years of precedent. They made aesthetic advances in the form of subtle variations on familiar formats (such as the precise shade of a celadon glaze), and a knowledgeable and demanding audience judged their efforts.

The three founding members of Sodeisha grew up in this milieu. All three were sons of potters who had come from elsewhere, Suzuki's father to work as a wheel-throwing specialist in a prominent workshop and the fathers of Yamada and Yagi to train. In addition, they grew up in the shadow of Japanese militarism and xenophobia. Japan's long war against China had begun in 1931, when they were children. They had experienced the physical and emotional privations of the long period of strife, and as would-be artists they had also suffered from government censorship that severed their contact with the flow of ideas from the EuroAmerican art world. They had faced the certainty of military conscription. Fortunately, Suzuki and Yamada had just finished school when the war ended, on 15 August 1945. Only Yagi had been drafted into the army, and he was saved by contracting tuberculosis in China and being sent home to recuperate. But Yagi's brief military experience changed his understanding of his relationship to clay. Previously he had practiced a European-derived mode of "ceramic sculpture," an activity motivated in large part by his desire to distance himself from his father's work in the classic Chinese mode. As the son of a potter, he found himself using clay simply as a matter of course. He would later explain that he first truly understood the emotional importance of clay in Japanese culture on the day he ate from a metal mess kit and noted its difference from a ceramic rice bowl.

SODEISHA

With the war's end and the collapse of the ideological system that had led Japan into war, artists (like others) were full of questions about their personal and professional lives. A natural outcome was the formation of affinity groups, not only as a forum for urgent discussion and debate but also as a practical means of organizing exhibitions by sharing the expense of renting gallery space.2 Yagi recalled, in a biographical essay from which I will quote frequently, that just as "various groups were springing up like bamboo shoots after the rain, so we young potters drew together also. We wanted to make something new rather than embracing any orthodoxy. Moreover, we wanted to create a new life rather than living according to the old rules for doing things."3

In July 1948, Yagi, Yamada, Suzuki, and two other Kyoto potters mailed out postcards imprinted with the manifesto of their new group, Sodeisha. The postcard bore this statement:

The postwar art world needed the expediency of creating associations in order to escape from personal confusion, but today, finally, that provisional role appears to have ended. The birds of dawn taking flight out of the forest of falsehood now discover their reflections only in the spring of truth. We are united not to provide a 'warm bed of dreams,' but to come to terms with our existence in broad daylight.

The manifesto hinted at developments that had rapidly taken place in the three years since the war's end. The new group distanced itself from social and ethical concerns that had bound together many groups created immediately after the war, including one called the Young Pottery Makers' Collective (September 1946 - July 1948), to which the three Sodeisha artists had belonged. The new group focused on artistic and aesthetic issues, as its name indicated. Taken from a Chinese connoisseur's term for a glaze flaw in the Song dynasty glaze called Jun, "Sodeisha" sounded and looked (written with unusual Chinese characters) at once exotic, antiquarian, and comical. The manifesto's imagery, borrowed from European Surrealist poetry in which Yagi was well read, made clear that the young potters sought, not comfort from like-thinking comrades, but "the spring of truth" - engagement with difficult questions about themselves and their work. Yagi and his colleagues pursued a relentless intellectual and technical process of identifying the rules that bound them to established forms, products, and procedures, and systematically cutting themselves free.

THE ISSUE OF MODELS

Even before the founding of Sodeisha, Yagi and his colleagues made a fundamental choice to distance themselves from standard Kyoto ceramic forms derived from Japanese historical models. As Yagi explained, "We resolved never to make tea bowls, whether for exhibitions or under any other circumstances."4 Although we may view the tea ceremony, with its large repertory of ceramic utensils, as an enviably supportive market for potters, Yagi saw it as a prison of rules governing form and design, as well as personal behavior and relationship to one's patrons. Yagi's early negative contacts with the elitism of the hierarchical tea-ceremony world had turned him emphatically against it. "Tea bowl" was a code word for the "forest of falsehood" mentioned in the Sodeisha manifesto - for a formalism within the tea world that would stifle personal growth and self-discovery.

Instead, the Sodeisha artists turned to other Asian ceramic models - from China and Korea - that they had encountered during their training and on visits to museums. Their earliest works, such as the vase that Yagi showed in 1947 in the first group exhibition of the Young Pottery Makers' Collective, were based on the shapes of Chinese Cizhou ware. Cizhou ware had been extremely popular with collectors in Japan throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and during the 1920s and 1930s many Kyoto potters had worked in the Cizhou format. For Yagi, however, the choice of a Chinese Cizhou vase form represented a conscious rejection of standard Japanese ceramic forms.

THE ISSUE OF DECORATION

Cizhou ware also provided a useful format for exploring the issue of decoration on ceramics -specifically, the question of how to introduce decoration that acknowledged the innovative work of European artists. When Yamada met Yagi for the first time, in 1946, Yagi showed the younger man book and magazine reproductions of prints and paintings by Picasso, Paul Klee (1879-1940), and others and declared, "Drawing is everything."5 It was natural that the Sodeisha artists first addressed the decoration of their ceramics as the field open to significant change.

Standard Cizhou ware was coated with white slip and always bore decoration - either painted in iron over the slip or incised through the slip to the dark body - coated with clear glaze. On his 1947 jar, Yagi incised his design, but rather than replicating the standard Cizhou motifs of conventionalized peonies or dragons he sketched a continuous composition of five large sunflowers, rendered as though drawn with blunt pencil.

Standard Cizhou ware was coated with white slip and always bore decoration - either painted in iron over the slip or incised through the slip to the dark body - coated with clear glaze. On his 1947 jar, Yagi incised his design, but rather than replicating the standard Cizhou motifs of conventionalized peonies or dragons he sketched a continuous composition of five large sunflowers, rendered as though drawn with blunt pencil.

But Yagi quickly moved beyond this sort of realistic rendering. As he later wrote, The work of the Surrealist Max Ernst appealed to me, and when I returned from my fierce role as a soldier my feeling had not changed. Later, I felt an even stronger attraction to the work of Paul Klee as it was introduced in magazines.6

I liked Paul Klee's 'thinking line'. I wanted to draw on my jars with that line ... 7

I tried incising lines on the jar forms that I somehow raised with my imperfect throwing. My father laughed at me. 'No matter what you draw, it comes out Surrealist.8

For rendering crisp lines that conveyed the sharpness of etchings, Yagi turned to the technique of slip inlay developed in Korean ceramics from the twelfth century onward. Finely incised lines were filled with white or black slip, with the excess brushed away, then coated with clear glaze. Later inlay employed stamps and used only white slip, often brushed freely over the surface and not cleaned up.

For rendering crisp lines that conveyed the sharpness of etchings, Yagi turned to the technique of slip inlay developed in Korean ceramics from the twelfth century onward. Finely incised lines were filled with white or black slip, with the excess brushed away, then coated with clear glaze. Later inlay employed stamps and used only white slip, often brushed freely over the surface and not cleaned up.

Just a year after the sunflower vase, Yagi exhibited another Cizhou-style vase that showed startling advances. The form was tall and elongated, and the Chinese-style spatial divisions were only summarily indicated. A thick, smooth coating of white slip formed the ground for images of four abstracted sunflowers evenly spaced around the jar. The black lines were not painted, but incised and inlaid with black slip. Yagi's title for the vase, Corona, was not the usual technical description but an allusion to the resemblance of the tiny petals surrounding the seed head to the corona of sunlight that surrounds the moon during such an eclipse. The choice of title related to his goal for his work:

Rather than pursuing the kind of beauty that was to be found in ceramics, I had a very strong feeling of what I wanted to express. Rather than the ordinary appearance of ceramics in the mode of Chinese or Korean wares, or the process of making such wares, I wanted to make concrete through the medium of ceramics something - you can call it romantic - with the essence of the literary world.9

Corona won the Mayor's Prize in the Kyoto-wide exhibition. Yagi defended another work in this same series to a senior Kyoto potter by claiming boldly that it combined "Chinese form and Cubist methods in the drawing". For several years all three Sodeisha artists experimented with unexpected contemporary decoration on the Cizhou form. Suzuki's 1950 vase Rondo may well reflect his encounter with a photograph of a Jackson Pollock drip painting.

THE ISSUE OF FORM

By 1950 or so, however, the standard Cizhou vase form itself became problematic. The Sodeisha members recognized that new modes of decoration could go only so far if the vessel form was based on a classic Asian ceramic mode. They vowed to cease making copies of any historical wares. More fundamentally, they began to question the nature of the conventional vessel form - a container with a single opening centered at the top. They experimented with making vessel forms with multiple, off-center mouths, but they also spoke of "closing the mouth of the vessel" - eliminating conventional function altogether. Yagi recalled the encounters with asymmetrical, non-functional ceramic sculptures by non-Japanese artists that inspired them:

Determined to be forward looking, we were extremely susceptible to new movements in the arts. Just at that time ceramics made by people like Isamu Noguchi and Picasso were introduced to Japan. For us they were a tremendous shock. We knew China, Korea, Japan, and what had grown out of those traditions. We realized that we wanted to develop in Japanese terms something that had not previously existed - to follow our own hearts, without being guided by the materials or techniques of foreign artists ... Thus, if we talk about influence, [the foreign artists' works] showed us that we had to liberate ourselves - that is, free ourselves from the spell of ceramics, and to do this by our own hands as potters.11

By "the spell of ceramics" Yagi meant the sensory and emotional appeal of classic Asian forms and glazes. His 1950 Jar with Two Small Mouths departed both from wheel-thrown symmetry and from obvious function by mounting a wheel-thrown ovoid on its side, then attaching two small mouths angled toward one another in such a way as to preclude any use. The decoration - inlaid black lines accented with spots of primary color - reflects Yagi's reverence for Mira's paintings and prints. Suzuki Osamu's 1951 Two-headedJarpositioned two large openings at either end of a hand-built, horn-shaped body. Yamada's 1953 Jar with Cut Accents altered a wheelthrown Cizhou-like bottle form by replacing part of the wall with slab constructs and setting the mouth off-center, as through creating a three-dimensional version of a Cubist drawing.

Much of this work bewildered the traditional Kyoto ceramics world. A Kyoto newspaper article about Yagi in late 1951 remarked, "Yagi Kazuo pulls from his old wheel the sort of avant-garde works that cause senior potters to avert their eyes."12

THE ISSUE OF THE POTTER'S WHEEL

The Sodeisha artists recognized that conventional ceramic form was dictated by use of the potter's wheel - the tool they had been trained to revere as essential to the Kyoto potter's craft. They realized they would have to wean themselves from the wheel and turn to handbuilding methods in order to attain new forms. Such forms became known as objet, borrowing the term used by French Surrealists for sculptures composed of everyday objects removed from everyday life. Yagi explained,

Why did we begin making objet? Speaking from the actuality of making ceramics, no matter how much one might intend to make something new, if one makes it on the wheel, it will be round and symmetrical. The maker then asks what sort of design to put on this shape, then what sort of glaze will go best with this kind of design ... One cannot escape from the symmetrical sensitivity produced by the wheel.13

We realized we had to create our own alphabet in terms of how we made our work, and thus we began making objet. It seemed that this would allow us to develop freely.14

It was Yagi who pushed this tendency over the edge in his landmark work Mr. Samsa's Walk (1954). In preparation for his first solo gallery exhibition in Tokyo in December, 1954, Yagi made a series of pieces using the potter's wheel to make thrown components that he then reassembled without regard to the orientation established by the wheel - a process already begun in 1950 Jar with Two Small Mouths. For Mr. Samsa's Walk Yagi laid a circular coil of clay on the wheel and threw a hollow doublewalled cylinder. Separately, he threw numerous small cylinders, cuttmg and rejoining them at angles. When he put these parts together, he imbedded some small tubes within the walls and attached others to the sides or edges of the walls. Three tubes became legs, allowing the large ring to stand upright on its side.

It was Yagi who pushed this tendency over the edge in his landmark work Mr. Samsa's Walk (1954). In preparation for his first solo gallery exhibition in Tokyo in December, 1954, Yagi made a series of pieces using the potter's wheel to make thrown components that he then reassembled without regard to the orientation established by the wheel - a process already begun in 1950 Jar with Two Small Mouths. For Mr. Samsa's Walk Yagi laid a circular coil of clay on the wheel and threw a hollow doublewalled cylinder. Separately, he threw numerous small cylinders, cuttmg and rejoining them at angles. When he put these parts together, he imbedded some small tubes within the walls and attached others to the sides or edges of the walls. Three tubes became legs, allowing the large ring to stand upright on its side.

This work amounts to a representation of the concept of a vessel, with the invisible "volume" made visible in the empty space within the ring and the usual single "mouth" multiplied and attached in all directions but the expected one, and three "mouths" even serving as "feet." This work is small, not even a foot tall; it exists within the space of a normal vase form. It is refined in its conception and its execution, as one would expect from the work of a Kyoto-trained artist. Its origin in wheelthrown components is critical, for the wheel-thrown cylinders in differing scales lend both harmony and structural tension. Responding to the wriggling tubes reaching in all directions, Yagi named his creation Mr. Samsa's Walk after the protagonist of Franz Kafka's 1915 novel Metamorphosis, about a man who turns into a cockroach and learns anew how to walk on his multiple legs. We might call this work the metamorphosis of a vessel. Mr. Samsa's Walk became the iconic work of Japanese postwar ceramic sculpture.

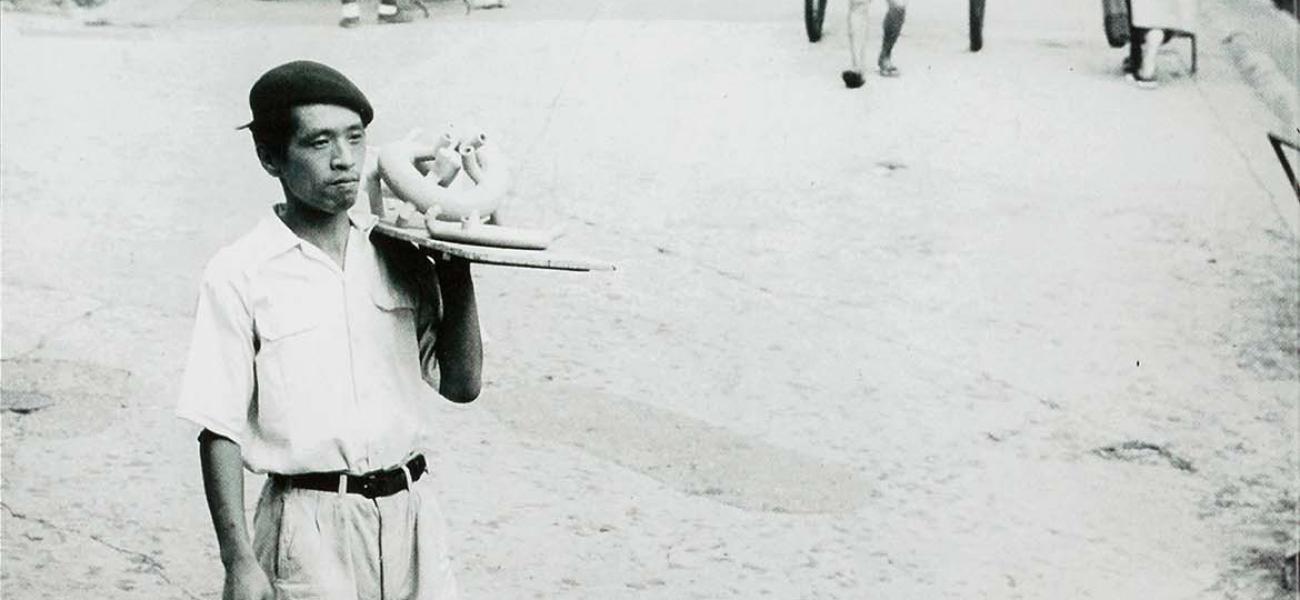

By coincidence, the production of Mr. Samsa's Walk and other works in the series was documented in photographs taken for a Tokyo newspaper. The article, discussing upcoming events in the art world, described Yagi as a "samurai of the avant-garde ceramic world". A positive review of Yagi's Tokyo exhibition described the works as "clay objet passed through the fire". Thereafter it became standard to refer to the sculptural ceramics made by Sodeisha artists as objet or by the ironic hybrid term "objet ware" (objet-yakz) that echoed their source in regional ceramic wares.

THE ISSUE OF GLAZE

form to show clearly. The white scars left by wads of coarse clay used to stack the large ring in the kiln were not removed or disguised. The next step for the Sodeisha artists now focusing on form was to abandon glaze altogether.

In their adoption of unglazed clay, they were inspired immediately by Noguchi's unglazed ceramic sculptures made in Rosanjin's studio in 1952. Noguchi had simply followed Rosanjin's practice of making table ware or tea utensils in unglazed regional clays such as Shigaraki or Bizen - a practice that originated in the admiration of sixteenth-century tea masters for unglazed storage jars from the Shigaraki and Bizen kilns.

The Sodeisha artists began using unglazed Shigaraki clay not primarily because of this historical association, but because Shigaraki was the main source of clay for Kyoto potters. When fired in the wood-fired communal kiln, the unglazed clay took on a ruddy hue. The earliest such Sodeisha works are quite pale, however, because the young artists could only afford to rent the cool spaces at the upper rear of the kiln chamber, where good color did not easily develop.

The unglazed works reveal even more clearly than the earlier glazed pieces the skillful touch of the Kyoto-trained artists. Yamada's constructivist piece Work (1958) is composed of assembled components, producing a complex hollow structure that changes dramatically from different angles. Yagi's 1959 Work No. 51: Memory of Clouds is sensuously smoothed and textured with a combing tool scraped rhythmically over the gritty clay. Suzuki's 1959 Wild Samurai retains a rough edge of ruddy-red Shigaraki clay that contrasts with the geometric block-printed decoration in black on the central panel of white slip.

In the early 1960s, Kyoto ceramics changed fundamentally when the city government closed down the woodfiring kilns over the issue of air pollution. Potters were provided with the means to install gas or electric kilns. When the Sodeisha potters began firing unglazed works in electric kilns, they learned to apply a thin spray of iron oxide to make up for the kiln's inability to draw color out of Shigaraki clay. This surface is visible in Yagi's 1961 work Monument: Queen Consort, his 1963 Wall, and Suzuki's Clay Figure (1965).

THE ISSUE OF HISTORICAL REFERENCE

Just once, in 1966, Yagi tried working and firing in Shigaraki itself, using the giant multi-chamber climbing kiln of a local factory. His pieces made for that firing are playful parodies of classic Shigaraki jar and vase forms. In contrast to the earlier difficulties of firing in Kyoto, these works were placed in the front of the chamber where they would accumulate wood ash to form a natural glaze. The most notorious piece happened by accident, when two molded figurines of Shigaraki's trademark garden sculpture, the folkloric creature called tanuki, fell from a shelf onto a tubular Yagi work shaped like an ancient Shigaraki drainpipe. (Writers have often given Yagi credit for creating the ironic juxtaposition.) Regardless of the public appreciation for these works, Yagi was not interested in repeating the experiment, declaring that he did not trust the temptation to rely on chance in place of thought.

Yagi had already become suspicious of the association of the "Shigaraki" surfaces of his sculpture with the tea-ceremony reverence for ancient Shigaraki storage jars. By 1957 he began using a firing process that had few historical associations in Japan (except for inexpensive earthenware bed-warmers, fueled with charcoal, and jars for saving partially-burnt charcoal overnight). This process involved burnishing the damp clay forms before firing them to a low temperature in a small updraft kiln. Stuffing moistened pine needles into the kiln at the end of the firing produced heavy smoke and coated the porous clay with black soot. This "black pottery" bore a color integral to the clay surface, and the blackness gave a powerful density to the form. As represented in Untitled (1958), Yagi began pairing the black forms with wooden bases of his own making, effectively contrasting color and texture. By 1964 he had perfected the techniques and prepared an entire one-person exhibition of black pottery. Some forms made for this exhibition were composed from small sheets of wrinkled clay (Human Figure); others had smooth, sharp-edged shapes (Queen). Yagi made larger forms as well that year, such as Letter or the work he considered his black pottery masterpiece, Maki.

Until Yagi's abrupt and premature death at age sixty-one in 1979, he executed his major work in the black pottery format. Many of the last works were enriched by the addition of slabs of dull lead or coatings of cinnabar red pigment.

THE ISSUE OF EXHIBITIONS

In addition to a systematic severance from conventional ceramic decoration, form, and even coloration, the Sodeisha artists also addressed issues relating to the organization of the art world. The masters who dominated the pottery world in Kyoto earned prestige by winning prizes in the ceramics division of the annual government-sponsored national exhibition or by being invited to make objects for the imperial household. The annual exhibition had first admitted potters to a newly-created crafts division in 1926. In the late 1930s, Yagi had already tried to escape this category by submitting his ceramic sculpture to the sculpture division, although his father was strongly opposed. (His submission was rejected.) For several years after the war, all three Sodeisha artists successfully submitted work to the government exhibition. Without question that recognition was important. As Yagi said, "With this, I could put on the face of an artist when walking up and down Gojozaka ... Until then I had not walked in the center of the road but stayed to the side."16

In addition to a systematic severance from conventional ceramic decoration, form, and even coloration, the Sodeisha artists also addressed issues relating to the organization of the art world. The masters who dominated the pottery world in Kyoto earned prestige by winning prizes in the ceramics division of the annual government-sponsored national exhibition or by being invited to make objects for the imperial household. The annual exhibition had first admitted potters to a newly-created crafts division in 1926. In the late 1930s, Yagi had already tried to escape this category by submitting his ceramic sculpture to the sculpture division, although his father was strongly opposed. (His submission was rejected.) For several years after the war, all three Sodeisha artists successfully submitted work to the government exhibition. Without question that recognition was important. As Yagi said, "With this, I could put on the face of an artist when walking up and down Gojozaka ... Until then I had not walked in the center of the road but stayed to the side."16

Soon, however, they declared an end to submitting to such juried exhibitions and vowed that they would exhibit their work only under circumstances they could control, even though this made their access to public attention much more difficult. They began holding their own annual week-long exhibition in Kyoto in 1948, and from 1951 onward they also showed annually in various locations in Tokyo. In Kyoto, they negotiated within the intricate politics and hierarchies of Kyoto ceramics; in Tokyo, they came under the scrutiny of nationally-known critics and collectors. As the numbers of private commercial galleries gradually increased, they offered additional venues. Yagi held his first one-person shows in galleries in both Kyoto and Tokyo in 1954; Yamada and Suzuki showed together in Tokyo in 1955.

Even earlier, though, work by the Sodeisha members found an international stage. The first Japanese art exhibition to be held in France after the war was an exhibition of contemporary ceramics that opened in Paris in November, 1950. Selected by the Japanese art historian Koyama Fujio (1900-1976) and the French scholar Rene Grousset (1885-1952), the exhibition included an extraordinarily wide range of work, from established masters to the three young Sodeisha artists. The popular exhibition was sent to Vallauris the following summer, where Pablo Picasso was among the visitors. In 1951 the Sodeisha artists were among fifteen ceramic artists selected (again by Koyama) to send work to an exhibition at the ceramic museum in Faenza, Italy. In addition, in early 1950, three of Yagi's vases with "Cubist decoration" in black on white were purchased by Noemi Raymond, wife of the architect Antonin Raymond, and sent to New York, allegedly to be shown in the Museum of Modern Art. Yagi achieved individual success in the international spotlight in 1959, when he won a grand prize at the exhibition for the Second International Congress of Contemporary Ceramics in Ostend, Belgium, and in 1962, when he received a gold medal for his work Monument: Queen Consort at the third International Academy of Ceramics exhibition in Prague.

THE ISSUE OF THE POTTER'S IDENTITY

In 1956, the sculptor jurying the sculpture division of the annual Kyoto municipal exhibition invited Yagi to submit work to that division, but the prominent potter who was judge of the ceramics category insisted that Yagi's work could only be shown there. In a statement to the press, Yagi defined his distinction between the two categories:

In 1956, the sculptor jurying the sculpture division of the annual Kyoto municipal exhibition invited Yagi to submit work to that division, but the prominent potter who was judge of the ceramics category insisted that Yagi's work could only be shown there. In a statement to the press, Yagi defined his distinction between the two categories:

Sculpture is essentially expression and is unconditional, whereas for craft there has to be an owner to use the piece or to look at it. I doubt whether the work I would like to submit would be recognized as craft, and I myself don't think of it as craft.18

Nonetheless, Yagi often referred to himself, with ironical humor, as "just a rice-bowl maker (chawanya)". Even though Sodeisha artists presented abstract sculptural works in their group shows and solo exhibitions, they did not abandon utilitarian ware as an everyday mode of production (and income). They perceived no conflict

in following both modes of production simultaneously. In 1962 (the same year that Yagi won the grand prize in Prague), Yagi and Yamada collaborated to produce a line of hand-thrown tableware under the name Mon Kobo (Gate Workshop). All three artists worked regularly in the domain of industrial design, creating prototypes to be replicated through molding.

The stance that Yagi and the others adamantly refused to accept, however, was that of the artists who received government designations through the so-called "Living National Treasure" program that began in 1952 and was revised in 1954. The designations primarily recognized potters who had revived historically-important Japanese ceramic modes, such as Arakawa Toyozo's recreation of Shino and Black Seto ware or Kaneshige Toyo's revival of Bizen firing methods. Yagi was deeply suspicious of the frame of mind required to recreate an established mode, feeling that it involved self-deception. For example, Yagi analyzed Arakawa's work after seeing a television program about the older potter. Yagi had often wondered how a contemporary potter could successfully replicate the irregular forms of the sixteenth-century Shino tea bowls, since "in old vessels the boundary between what is created and what simply happens is ambiguous." He was dismayed to see that Arakawa intentionally managed his throwing to create "the sort of irregularity that makes pottery lovers weep". Arakawa kept insisting to his interviewer, "It has to be natural," but Yagi perceived that, for Arakawa, "natural" and "artful" were not contradictory but inseparable. Yagi protested that the Living National Treasures

have swallowed up the beauty of Mino, let's say, or Bizen, and the criticism directed at such artists revolves chiefly around the accuracy and skill with which they represent that beauty. Unlike the old pottery of China, which may be said to have an eternal objectivity, old Japanese ceramics belong to a mental state full of irrationality.20

Yagi also refused to be deceived by the "natural" mode of work represented by potters who worked under the wing of the Folk Craft Movement. Just as Arakawa persisted in operating a highly inefficient sixteenth-century style kiln in order to fire his Shino tea bowls, the mingei potters were obliged to adhere to expensive, inconvenient, and outmoded processes that the leaders of the Folk Craft Movement deemed appropriate. "Within the context of folk craft," Yagi criticized, "the object itself has no connection to the logic of production."21

Whether as sculptors or as designers of tableware, the Sodeisha artists strove for intellectual honesty and consistency. Yagi's appreciation for the ceramic work of Isamu Noguchi centered on the coherence of the forming process and the final form.22 Form as transformed by painting was the critical issue in Picasso's ceramics:

Whenever it was that I first saw a catalogue of Picasso's ceramics, my whole body began unexpectedly to tremble. Until then I had viewed pottery made by painters with the eyes of a potter, but now I seemed to feel myself being examined by that painter's pottery, and I became aware of my standpoint as a potter. The effect was not to make me reconsider the inherent functionality of pottery. Rather, those pots wore ironic expressions as they seemed to point out the vagueness of my grasp or interpretation of the more fundamental nature of pottery per se.23

As promised in the Sodeisha manifesto, Yagi and his colleagues were not looking for reassurance in the work of artists who inspired them; they wanted to be challenged.

CONCLUSION

It is instructive at this point to contrast once again the activities of the Sodeisha artists and of Peter Voulkos and the other Otis artists. They appear to have so much in common, even as the trajectories of their work were so different. The Japanese artists and the American artists, although completely unknown to one another, shared similar goals: to cut their ties to prevailing models of ceramics, to move ahead unencumbered to make something new. As the Japanese artists worked determinedly to free themselves from the formalism and irrationality of traditional Japanese ceramics, the American artists sought to break with the "formalist regime of the European object" and "demands for perfectionist craftsmanship".25 Both groups looked to Picasso for new concepts of "decorating" ceramics.26 Both began with a new vision for the vessel, then proceeded to the formation of the idea of ceramic sculpture.27

The Sodeisha achievements reveal that avant-garde ceramic work does not have to be large, muscular, and rough. The scale of Sodeisha works is personal, intimate, never too big to take in at a single glance; it maintains a comfortable relationship to the size of the viewer. The scale of the work also relates to the size of the artist's hand and body, and thus to the capacity for meticulous workmanship. Many other factors lie behind this concept of scale, ranging from the appropriate size of objects made to be viewed in the display alcove (tokonoma) of a Japanese room to the limits of space in the cooperative kiln. Perhaps the scale relates also to the enduring importance of the art book or journal as a source of reference and inspiration. Yagi did a series of book forms, while numerous other works, constructed as "walls" with two flat surfaces joined back-to-back (such as the slip-coated Wall of 1964) or as boxes, reveal a continuing reverence for two-dimensional graphic forms. In the mature work of the Sodeisha artists, executed in distinctive styles, the shift from vessel to sculptural form invites one to contemplate the qualities of clay and glaze for their own sake, stripped of the burdens of historical association. While postwar ceramics in the "folk craft" and "Living National Treasure" modes have enjoyed popularity in Japan as well as in Europe and North America, it is the exercise of self-examination by the Sodeisha artists that opened the way to a truly modern Japanese statement in clay.