Chinese Folk Pottery

Chinese Folk Pottery has a vitally rich and a continuously long tradition. The simple, unpretentious forms crafted with intuitive aesthetics and unconscious skill have evolved and distilled through the centuries. Scholars and connoisseurs tend to focus on the "finer" porcelains and the more elegant Imperial Wares rather than the timeless, simple common folkware. More recently, there is interest in and study directed to the historic "Export Ware," which were shipped from China by the junks sailing to the Philippines, SE Asia and as far as Africa. They also made long caravan journeys by way of the silk route to Bagdad, Damascus and beyond.

I first became aware of the vast ceramic history of Asia through a friend and mentor, the art historian James M. Plumer* at University of Michigan, where I had my first teaching job. In 1935 James Plumer discovered the location of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) Jian kiln site in the remote mountains of Fujian, SE China.

James Plumer's enthusiasm and passion for ceramics was contagious. He guided me through a journey in a fascinating and unknown world for which I am grateful. He told colorful and riveting tales of the dangerous and adventurous days when he lived and worked in China. I was most absorbed in his illuminating accounts of old kiln sites of Jun, Longquan, Cizhou, Jian, etc. which were exotic names I knew only as glazes. It became an irresistible urge to explore these mysterious places. Unfortunately, at the time when I was working in Japan it was the days of pre-Nixon Ping Pong diplomacy. Geographically, China was so close but politically inaccessible for Americans.

It was many years later that my wish was finally realized.

As for traveling in China, one cannot plan too carefully or assume anything. The journeys were often complicated and places difficult and arduous to reach, but the experiences of time, situations and people were more than satisfying. I had not imagined how overwhelming and exciting it can be to be immersed in the scattered Song Dynasty shards on a hillside where once a dragon kiln was belching flames. The mute shards in my hand became a vivid documentary past suspended with intimate voices from the Song potters.

During these trips I came to realize the demise and fate of contemporary folk pottery. Today, China is going through dramatic if not traumatic colossal changes at every economic, social, and industrial level which inescapably affect all its people. Many village potteries became commercial factories producing less than aesthetically interesting ware, while others with decreased demand had to drastically reduce production. This disturbing observation loomed over me. In 1998 I received a generous grant from Asia Cultural Council to research and document folk pottery in China. Although my focus has shifted from ancient to contemporary kilns, the path is not less difficult.

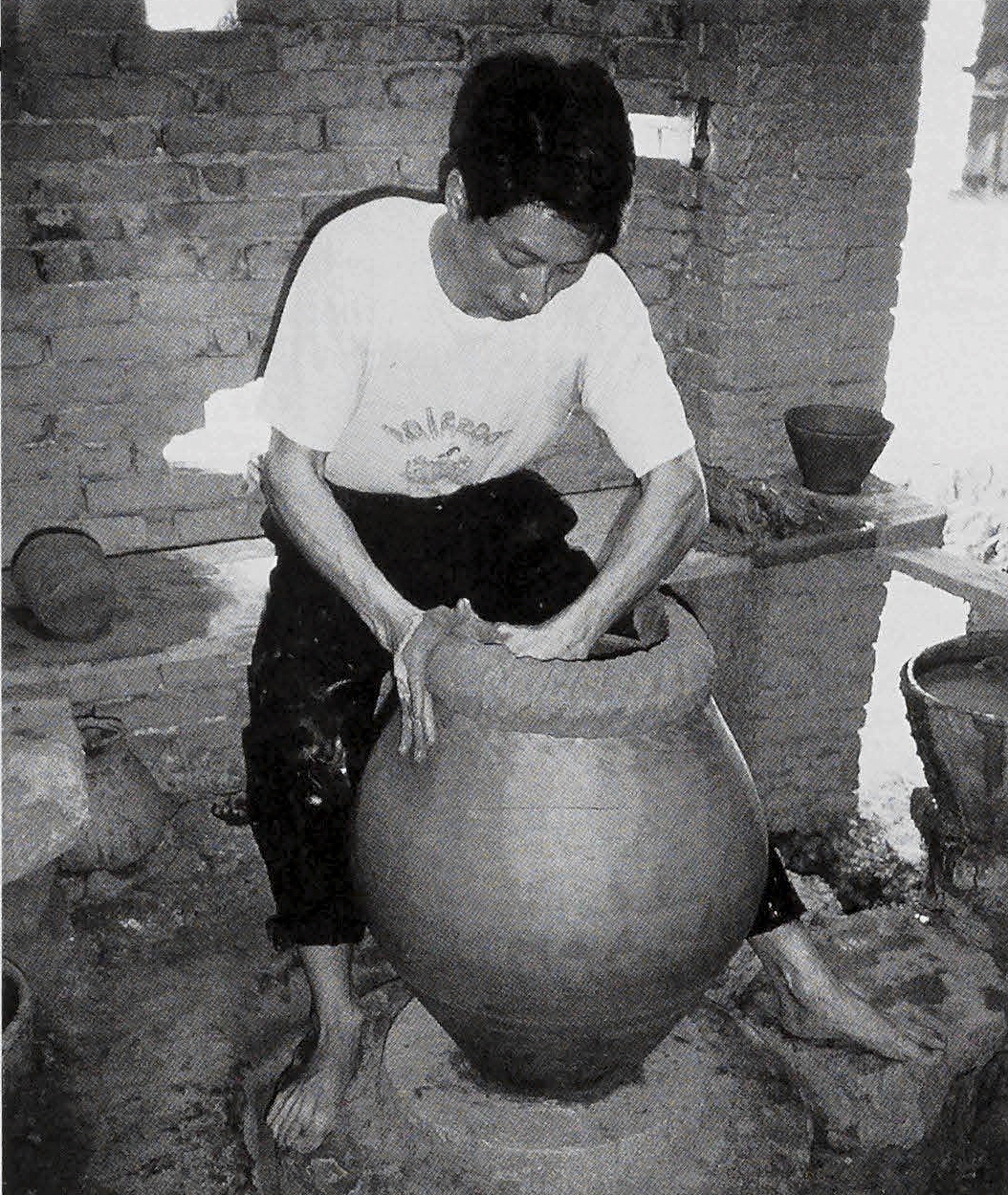

One such place is Cao JieVillage, located in the western province of Szechuan. It was a forty-minute boat ride from Chongjing on the wide Jialing River, a tributary of the Yangzi River. Potteries are usually located near available water transportation, as well as fuel and clay source. Then it was an excursion up the bank, through the timeless historic village, and a rigorous climb up hills and fields along foot paths. In less than an hour, we reached our destination to find a busy pottery in the familiar activity of stacking a large multi-chamber dragon kiln. The production is predominately stoneware storage vessels of every scale. The splendid three-foot field jars for holding water had jiggered bottom parts and the top halves were completed by adding clay coils and thrown on the wheel.

The lidded pickle jars are unique with a deep flange thrown on the rim. When in use the flange is filled with water and when the lid is in place, the water creates an interior vacuum which also keeps out crawling undesirables.This large kiln fires twice a month by coal, and the dark glaze is basically river slip and limestone.

Three hundred years ago there was military unrest in Hubei Province in central China that caused people to migrate west. Local lore tells the story of a rich land owner whose daughter was physically deformed, and her marriage to a local man was not such a likely prospect. But happily, a union was made between the daughter and an "outsider" who was a potter from Hubei. With this potter's ceramic knowledge and expertise they established and successfully operated the Cao Jie Pottery.

The pots were sold to all the surrounding villages and the pottery continued to prosper until recent times. Ten years ago, they had four dragon kilns firing with bellowing flames and today there is but one. It had supported a staff of four hundred and now it is reduced to only sixty workers. It is sad and difficult to accept what can happen in only ten years.

A dragon kiln is a tunnel or multi-chamber construction on a hillside. A large size can be 30- 50 meters long and hold thousands of pots. Wood or coal is the fuel which is fed into the fire box at the foot of the slope with additional stoke holes at successive interval chambers.

Advance kiln technology and knowledge of raw materials such a kaolin and feldspar enabled the early Chinese potters to be the first to achieve and excel in the art of high temperature ceramics.

There is one memorable and unique glaze application technique that was captivating.

There were huge field jars drying on top of the dragon kiln. A sure-footed worker carrying two buckets of slip glaze balanced on a shoulder pole climbed on top of the kiln, where he dipped and lifted a large cloth from the glaze bucket and then repeatedly and rhythmically sloshed the dripping cloth of glaze over the greenware. VOILA! Glazed pots!

Flying south to Kunming we proceeded by van on rough and scenic mountainous roads often shaded by eucalyptus trees. It took 12 hours to reach this western part of Yunnan Province near the Tibetan and Burmese borders inhabited by ethnic minority people who were friendly but culturally reserved and shy in manner. Our eyes feasted on these remarkable people adorned in colorful, sumptuous costumes, exotic jewelry, and extravagant hair designs. Their rituals, language and music are as unique and diverse as the customs and cultures of each specific ethnic group.

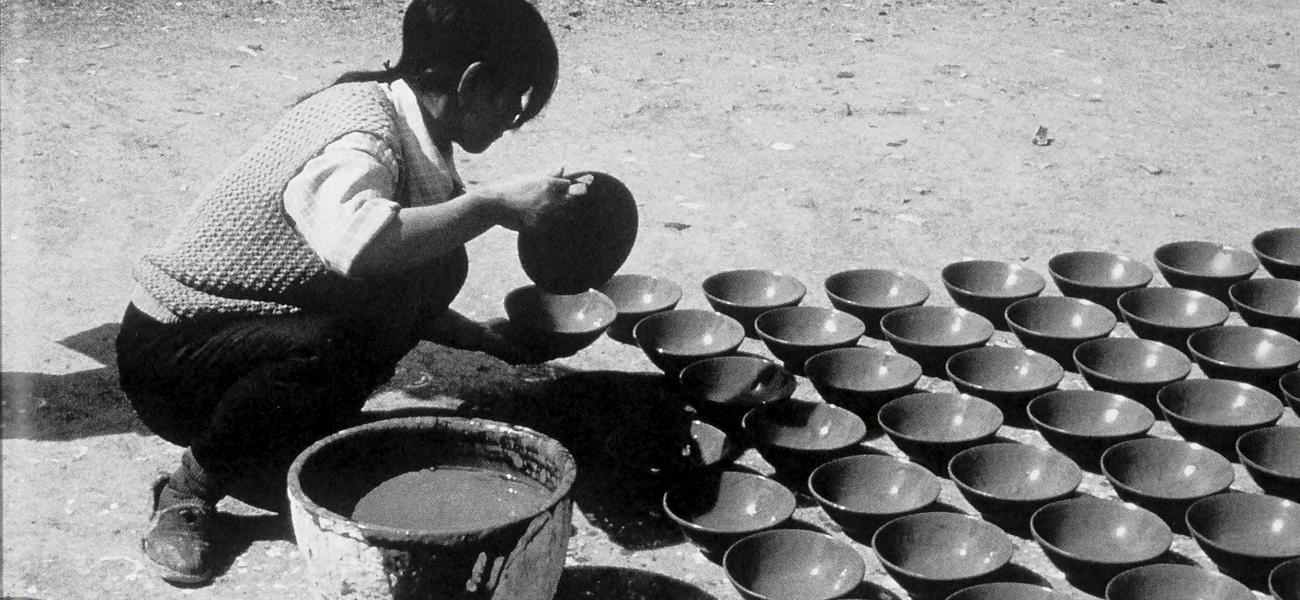

We covered more distance through unfamiliar terrain clad with wild, thriving rhododendrons. Then via the exotic towns of Dali, Lizhang,and Zhong Dian we explored a remote paper village, an indigo tie dye village, the dramatic Leaping Tiger gorge and enduring Tibetan temples in steep mountainous places where the driver was reluctant to go, so often it was by foot. The craftsmen in the Tibetan village of Tang Dui did wood carving as well as making black unglazed pottery. The construction method was basically hand formed pots on a concave wood turntable. The surface was burnished and some had bits of fired white shards embedded in the clay for surface decoration. The variety of pots included pitchers, storage pots, ladles, cooking pots, etc. The clay comes from the mountain and pots are fired on the open ground, obviously low temperature.

We reluctantly left the majestic mountains and began a long descent back to Kunming and by overnight train to Guiyang in Guizhou Province, east of Yunnan. Then, another rough and bumpy ride over hilly terrain in misty rain as dramatic formations of distant mountains became visible against a canvas of lush emerald vegetation. There was a woman washing her long black hair in the river. Four hours later we arrived on market day in a small farm village of Yazhou and waded through the mud and a curious, dense crowd of people who came to market. Just outside the village there was a small eight-chamber dragon kiln on a hill near the rice field. It is shared by eight families, one chamber for each, and the wood is provided by all the participating families. After eight hours of warm up it takes 24 hours to complete the firing.

When the first chamber reaches temperature it requires about two hours of stoking each successive chamber until final temperature is reached. Like the villagers, Yazhou pottery is simple and uncomplicated, made with unconscious skill. Variety of household ware include: teapots, pickle jars, press-molded clay pipes, and bowls with unglazed center for space saving stacking convenience in the kiln. They demonstrated throwing on a weighted wheel head close to the floor and propelled by a stick or foot. Pottery production is down thirty percent and the ubiquitous plastic ware is one obvious cause. Some potters have become stone workers for road construction, and the younger generation has gone to the cities seeking a "better life."

In contrast to those small village potteries that are threatened, there are the large thriving ceramic areas that have continued for hundreds of years that deserve mentioning. However, there is the inescapable mixed aesthetic qualities. Some of those areas are: LONGQUAN, located in the lush hills of Jijiang province, south of Shanghai, is noted for its thick, unctuous green celadon on light gray stoneware.

CHENLU/YAOZHOU in the western province

of Shaanxi produces the dark tenmoku, blue and white as well as the impeccable reproduction of the famous northern Yaozhou celadon.

JINGDEZHEN in Jiangxi Province is the famous porcelain center of China. It has a history of imperial kilns, but it also has its "private" kilns that still produce the blue and white underglazed porcelain as well as the serene qingpai (white glazed porcelain).

YIXING in Jiangsu Province has been known predominately for its "purple sand" teapots since the sixteenth century. They are made of very fine-grained, usually purple red stoneware that is burnished and unglazed. They are appreciated and collected by artists, poets, and tea connoisseurs.

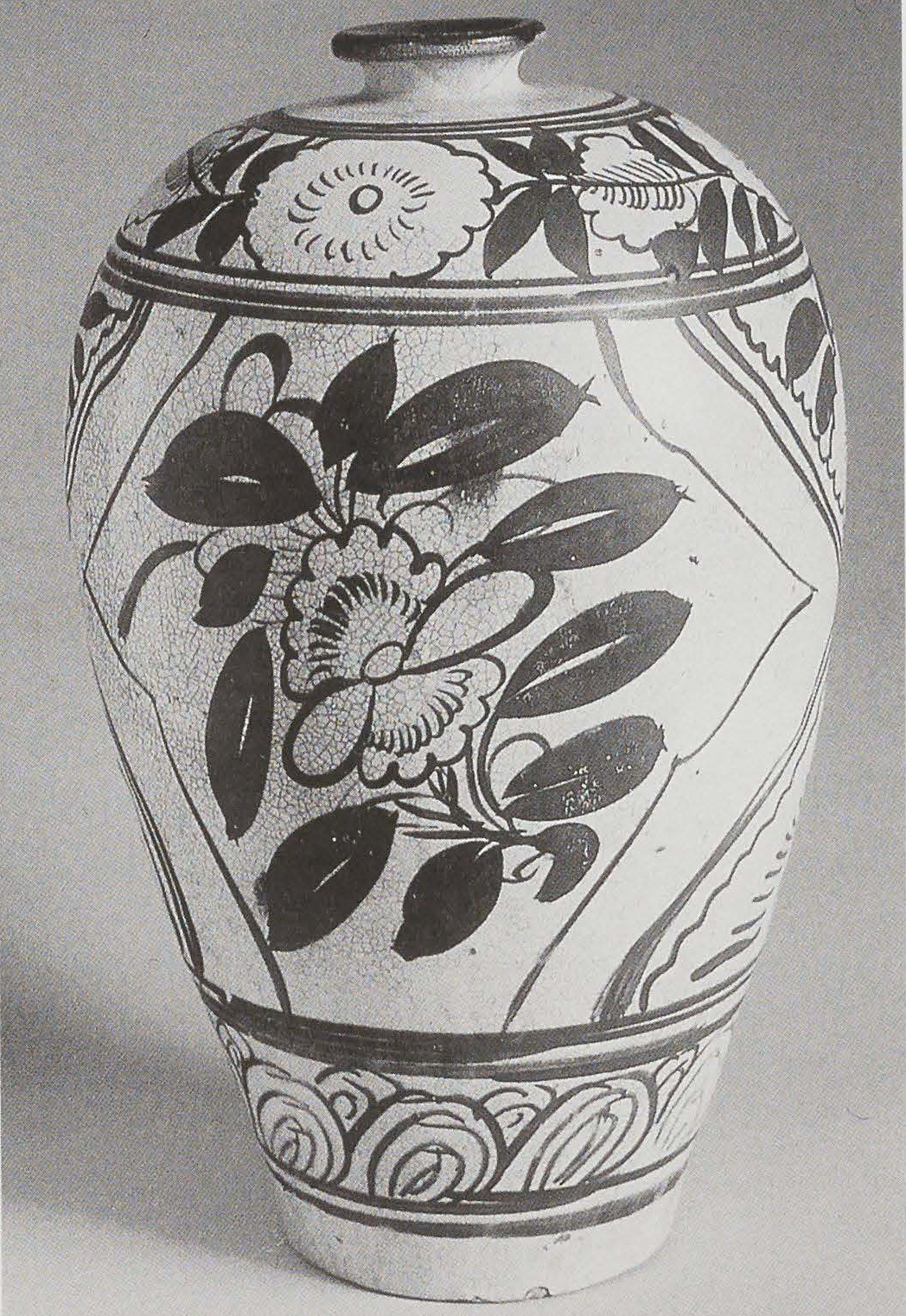

CIZHOU in Hepei Province is just north of the Yellow River. This popular stoneware has been produced in many areas in northern China since the ninth century. It is distinguished by the mastery of bold surface design motif inspired by nature, using varied techniques such as stamping, carving, sgraffito, and lively, spirited brushwork in combination or separately and applied with white and/or dark brown slips, then covered by a transparent glaze.

Concerning the precarious state of contemporary village potteries, I have recently learned of an encouraging development. My friend, Dr. Hsu I Chi, who publishes a ceramic newsletter and established the HAP Garden Pottery in Beijing, is now planning a sales/showroom for the purpose of representing Chinese village pottery. He has the keen insight to bring a positive presence to Beijing which will enlarge awareness and appreciation for the uninitiated. It is time to celebrate the humble, honest pottery of the common people and honor the ingenuity of the anonymous potter!