Catch and Release

At some point I began to feel the need for more structure, and one day, looking around the studio, I saw a round wooden bat. When covered with a mound of clay, the bat became a guide, resulting in a precise circular form that still had all the immediacy I wanted. To capture that solid form I began to use plaster, making my first molds. As more time passed, it dawned on me that the original bat had functioned as a kind of template. Obvious though it may seem now, the naming was an important aspect of my becoming conscious of possibilities—of my thinking's evolution beyond the initial use of a given, found object to an open-ended principle with broad implications.

By the time I began grad school at Alfred University the following year I had all the basic elements in place for a forming process that has served me to this day. My early templates were cut from steel, then litho plates, then masonite (hardboard), and are now sometimes laser-cut from acrylic. Though I eventually moved beyond wire-cutting, I still find the combination of template and clay has endless potential to form what we call the model or prototype in mold-making. Over the years, I have learned to see forms in terms of their profile, cross-section, contour; first delineated through a combination of planes, then given fleshed-out form when filled with clay, shaped, and modeled along the guidelines of the templates, molded in plaster, and slipcast. None of this may be apparent in the final result, but the process has led to new possibilities for ceramic form - work that simply couldn't have been made any other way. In addition to my students in mold-making classes, colleagues such as Bruce Cochrane and Andy Martin have picked up on this process to create bodies of work that elaborate on the unique potential of the template. Now as I begin to play with digital fabrication, I'm finding the years of studying form through a combination of outlines and profiles to have been an invaluable foundation.

Molds, as Tom Spleth has aptly stated, are a tool. As intermediaries in the forming process, they play a humble, unglorified background role, but they have had a central place in my thought process since I began working with plaster. There's something uncanny about seeing your intended idea first take a detour into absence. That the initial concrete manifestation of your form is a white, ghostly negative can itself alter your perception. Early on, this effect led me toward explorations, in both clay and plaster, of the negative, fossil-like space embodied in molds.

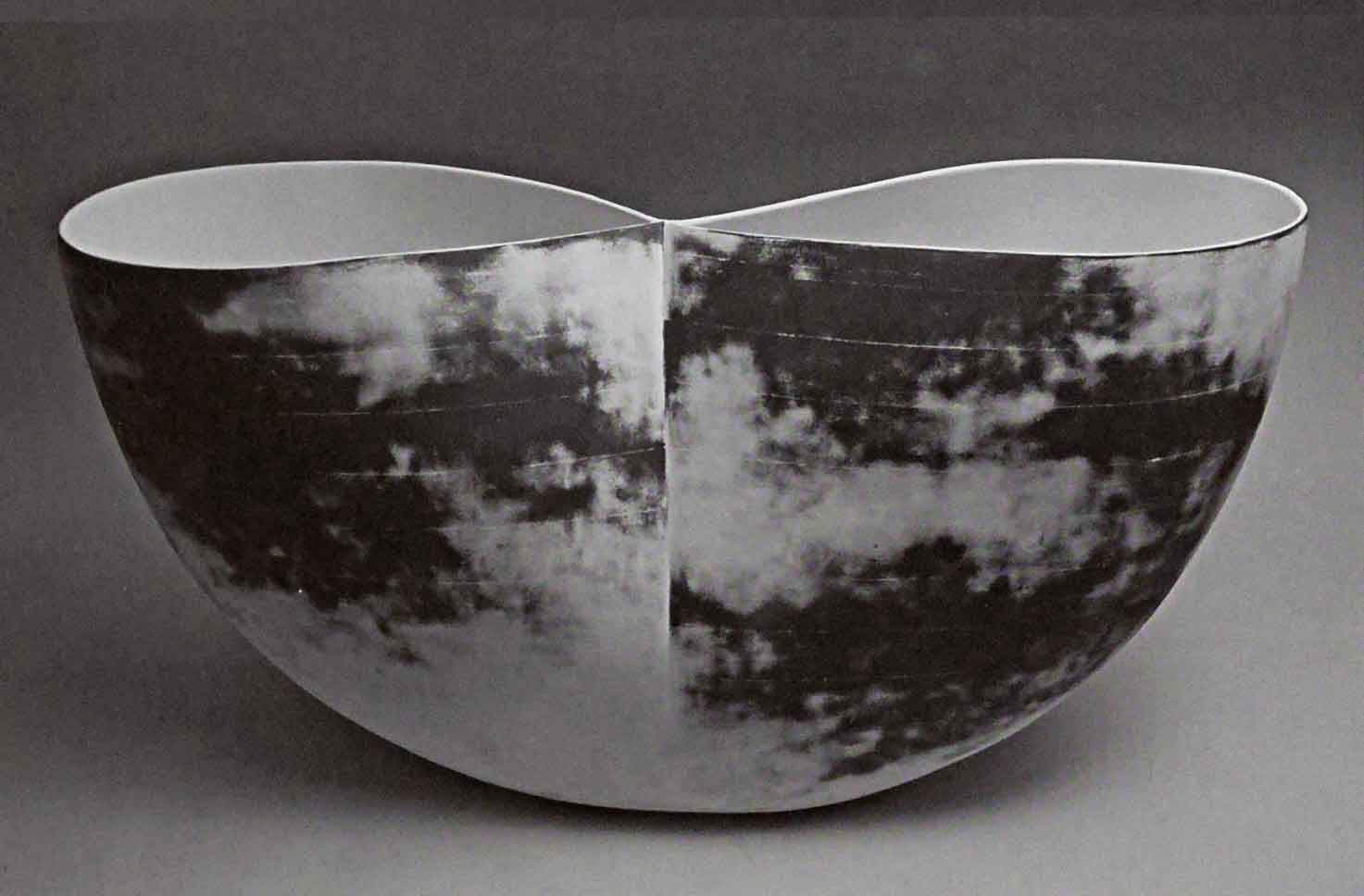

And while I did eventually move on to the more disinterested use of mold-as-tool, I still find myself captivated by their profoundly sculptural presence. For those who use molds in ceramics, the idealized representation of form captured in a plaster mold may ultimately bear only a distant resemblance to what the form becomes, as gravity, shrinkage, warpage, and firing each in turn have their say. Changes wrought by the forces acting upon a thin slip-cast object can be dramatic, even unsettling. But of course they also present opportunities, for those who like a little danger. One of the great lessons of my Alfred professor Tom Spleth's studio porcelain in the seventies was its very potterly embrace of effects such as warpage upon the molded object, immediately distinguishing the artist's intent from industry's use of the same technology (a key distinction in an era when the broad popularity of craft rested on evidence of the "handmade"). In the case of the slip-cast bowls and open container forms I returned to in the early nineties, I got used to hearing from people that they didn't realize those pieces came from molds, as they "seemed so organic." In contrast to the fairly strict geometry in which they began (defined by their base templates) the fluidity and lyricism resulted from what happened after their removal from the mold, as gravity kicked in. For example, a rim that was defined on the model as a crisp, geometrically true oval might be only loosely ovoid by the time the bowl was fired.

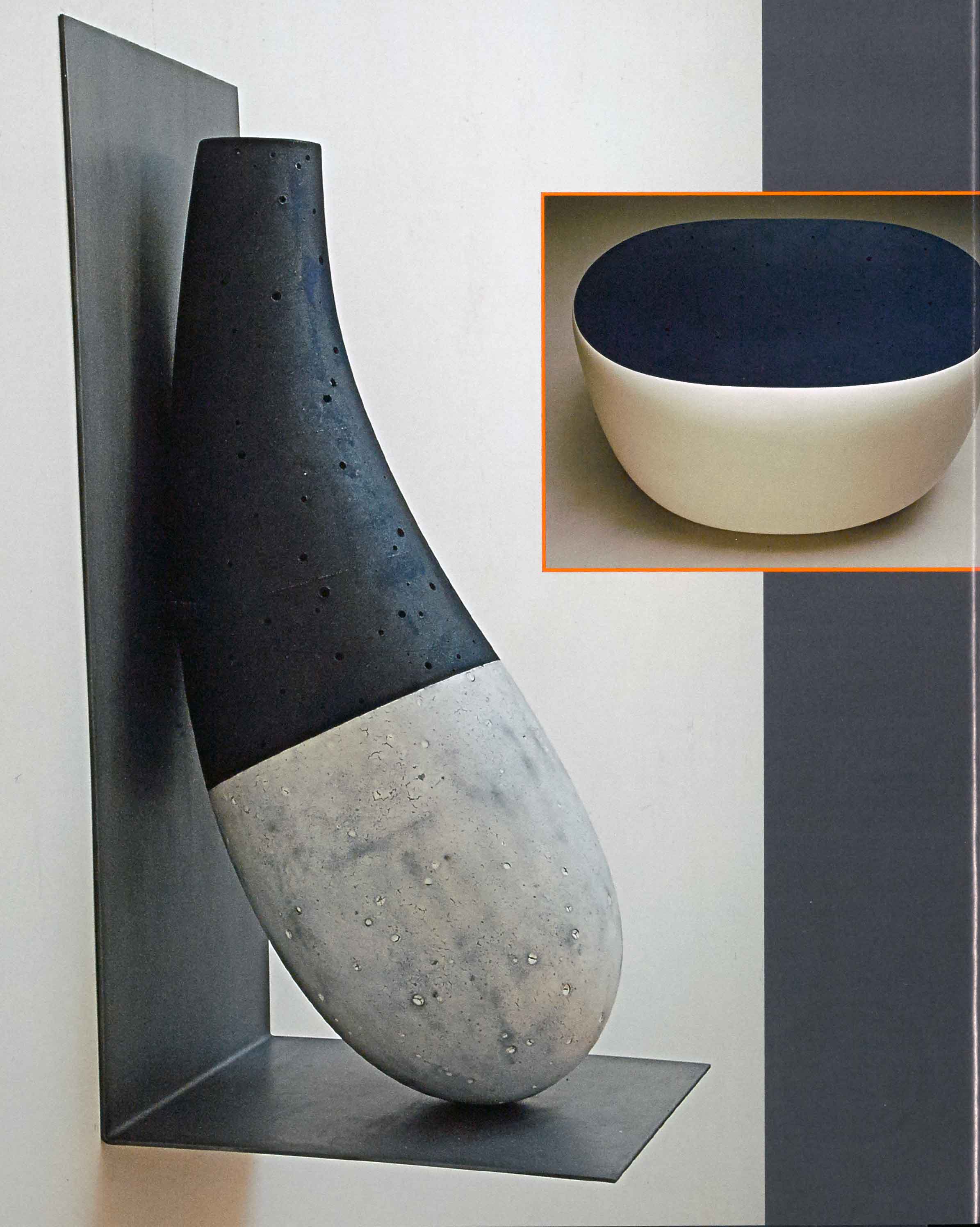

Then, several years ago, I found myself back looking at my plaster molds, pondering all their idealized geometry and precision. There was something there that I needed, some quality still to be brought to the ceramic work. After a time, what came was the notion of closing the open forms, essentially freezing some aspects of the geometric structure that were usually diminished by movement. I took a number of my earlier open plaster molds and made new slipcast versions by covering them with a plaster slab to enclose them during casting; the bowls were now closed forms, with a horizontal plane on top.

Since geometry was the driver in this development, I initially assumed that, well, the more the better. In other words, I felt I had to find a way to retain the absolutes of the planes in the firing process. I fired them upside down, and there they were: the geometries of the original prototype all intact. But as everyone who works in clay knows, there is a mysterious and subtle dance between intent and event, plan and accident, that often gives life to what we do. And while I had gotten exactly what I wanted, it wasn't ultimately what I wanted. I had no idea what these new things were. And as often happens they got shelved for a while, awaiting insights I didn't yet have.

Sometimes progress comes through holding on, other times by letting go. Having attempted the former, I eventually came to a more negotiable place. As it turned out, gravity once again came to the rescue, for it was only when I allowed the top plane to slump during the drying and firing that things began to hum. The forms now presented a shallow concave shape instead of a strict flat plane, and as the top slumped, it pulled on the sides, creating a more complex curvature in the walls—still strongly defined geometric shapes, but rendered somewhat softer and sexier.

Whether through vision or merely some perverse, ingrained, habitual way of seeing, the "container" element reemerged as the top plane drooped slightly, reminding me of things from the past: the kudlik, for example, a stone oil-lamp used in earlier times by the Inuit in Canada's north. I own a small, crescent-shaped one carved from soapstone from Baker Lake, and I have seen some very old ones that are more rectilinear. But what they all have in common is a shallow reservoir meant to hold seal oil, which would be lit with a grass wick. As objects, they embody that strange sense of purpose and no-frills economy; as tools they were instrumental to their owners surviving long winter months in warmth and comfort.

The shallow, concave space presented by these new "closed bowls" has been a wonderful thing for me to consider and explore. They seem to offer a fresh set of possibilities and a very different canvas from the one I've known. There's some drama in how this relatively small space is supported by a relatively massive form, a lavish expenditure way beyond necessity and more suggestive of ritual.

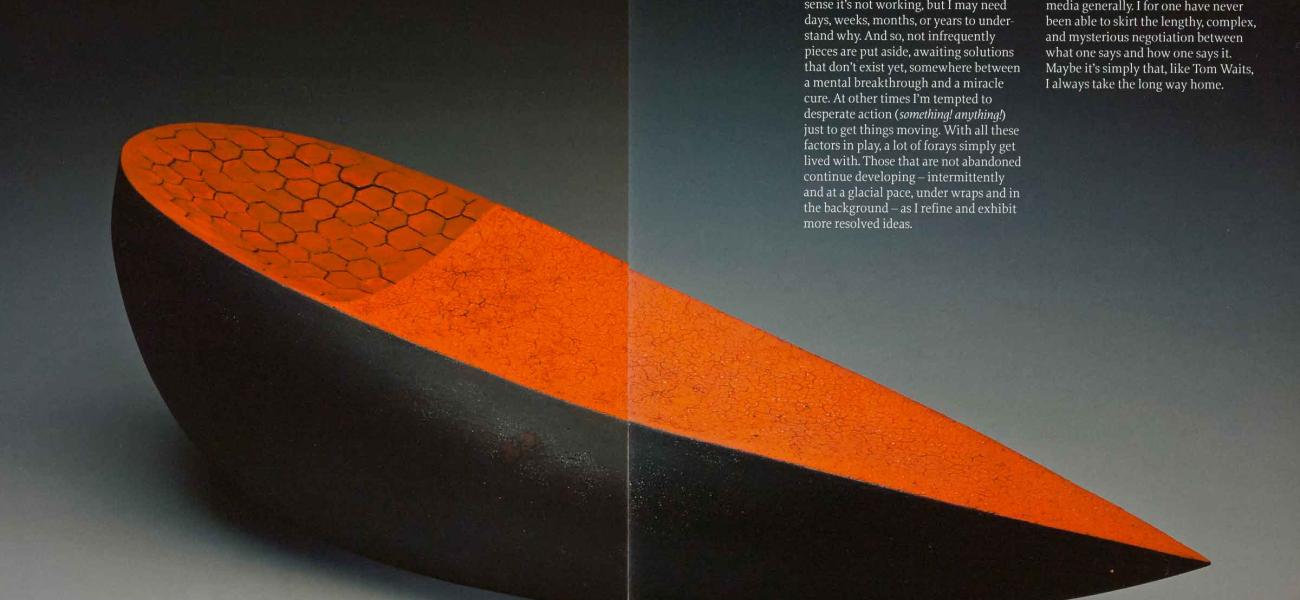

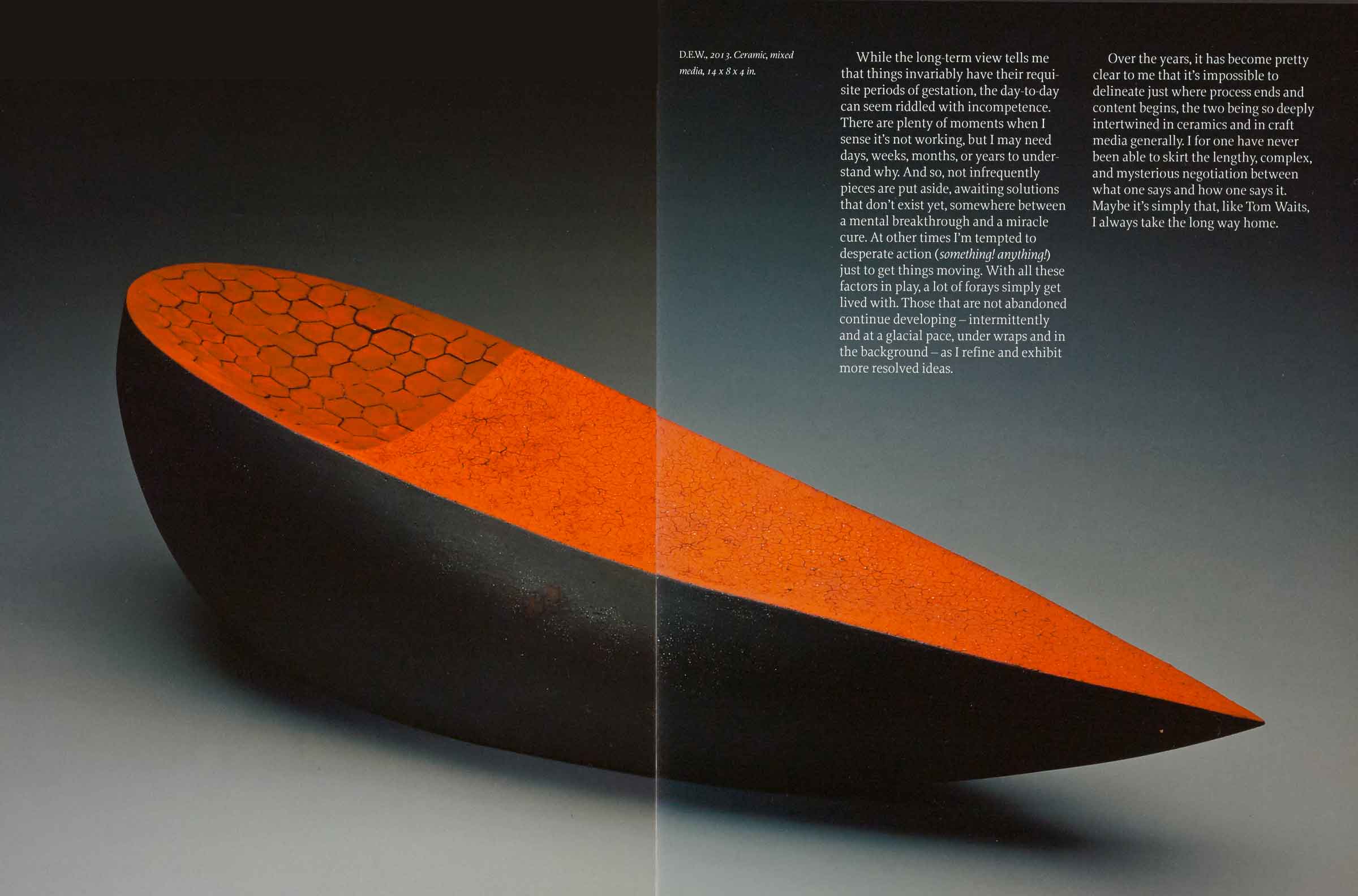

The surfaces of these new forms are an extension of approaches I've been developing for years: using layered stains, slips, and glazes over several firings, sanded or ground post-firing. Once the surfacing/glazing of the forms begins, I try to pay attention to what that space might become, knowing it may be something quite other than previous experience suggests. I consider a variety of solutions: articulating that top surface with a separate "slab" that is fired onto the piece; giving that slab its own treatment and metamorphosis, distinct from the form that supports it (D.E.W.); or perforating it to give some sense of the volume within (Kudlik).

of gestation, the day-to-day can seem riddled with incompetence. There are plenty of moments when I sense it’s not working, but I may need days, weeks, months, or years to understand why. And so, not infrequently pieces are put aside, awaiting solutions that don’t exist yet, somewhere between a mental breakthrough and miracle cure. At other times I’m tempted to desperate action (something! anything!) just to get things moving. With all these factors in play, a lot of forays simply get lived with. Those that are not abandoned continue developing—as I refine and exhibit more resolved ideas.

Over the years, it has become pretty clear to me that it’s impossible to delineate just where process ends and content beings, the two being so deeply intertwined in ceramics and in craft media generally. I for one have never been able to skirt the lengthy, complex, and mysterious negotiation between what one says and how one says it. Maybe it’s simply that, like Tom Waits, I always take the long way home.