Architectural Terra Cotta: 1900-1990

This is an innovation. It is indestructible and as hard and as smooth as any porcelain ware. It will be washed by every rainstorm and may if necessary be scrubbed like a dinner plate.1

The words quoted above were used in the 1894 Economist to describe Chicago's new Reliance Building designed by Daniel H. Burnham. This smooth and indestructible surface, which resembles porcelain ware, is actually a glossy, white glazed terra cotta cladding used to encase the steel cage construction of the building. Terra cotta brought a new expressiveness to the architecture and skylines of cities across America. Since the nineteenth century, building facades and rooflines have been ornamented with terra cotta, either in its natural clay colors or glazed with matt or glossy finishes. Vivid yellows, greens, and cobalt blues as well as metallic lusters of silver and gold emphasized lavish architectural detailing.

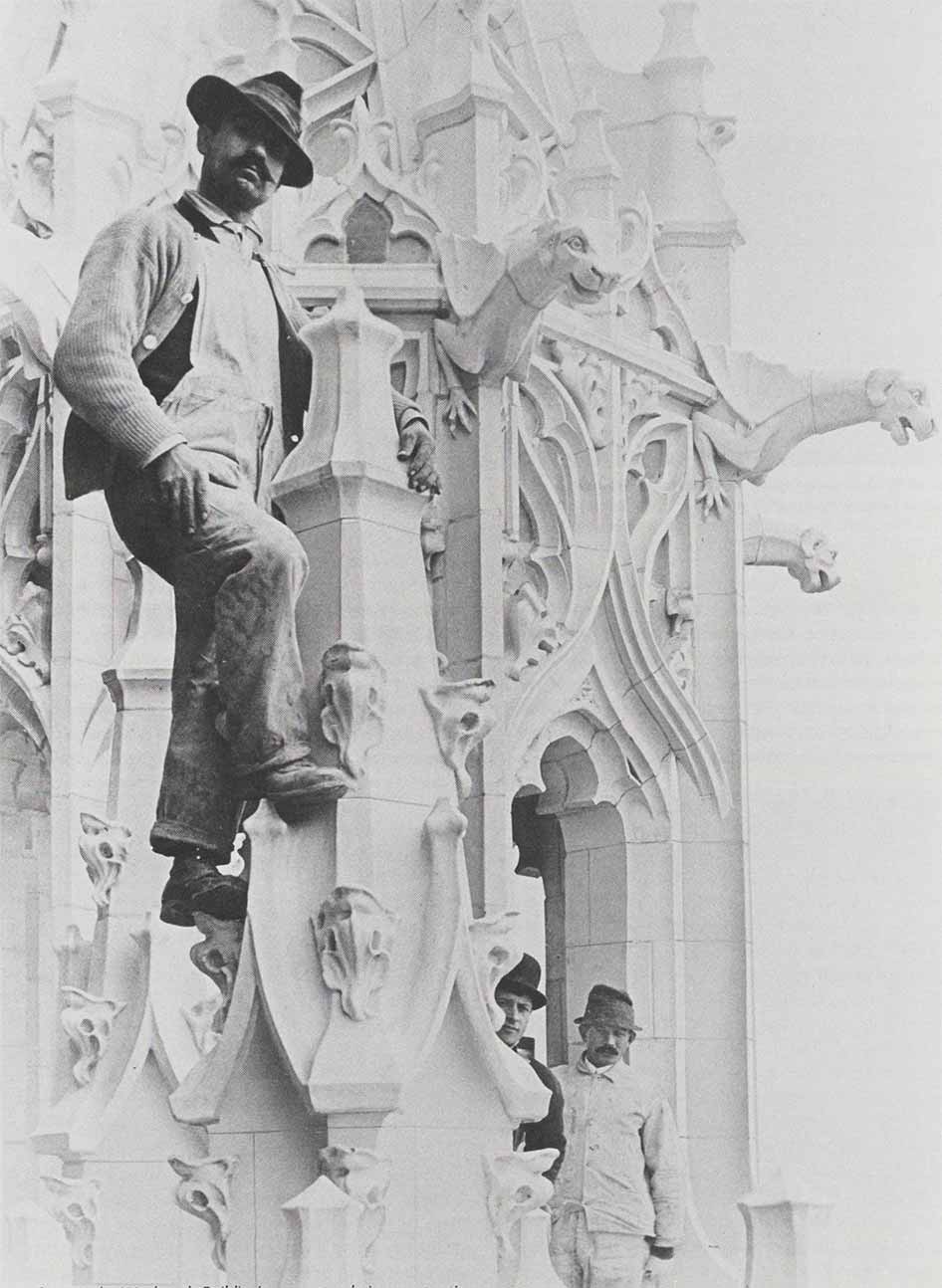

These vibrant colors marked a long period of extraordinary richness in building design. To the individual who appreciates abundant ornament, the architecture of recent decades has left a spare, even austere line of buildings devoid of both color and detail. But there is still pleasure to be gained by seeking out the architectural styles of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By looking beyond the severe, often banal lines of recent design, it is still possible to discover a gargoyle peering down from a neighboring building or to see an archway seemingly held aloft by winged cherubs. Above hastily modernized facades lie vast and varied displays of exotic imagery, color, and texture.

The material described in the 1894 Economist is the same used for architectural ornament in countless buildings across the country. Terra cotta, literally "baked earth," is a term that has been used loosely since Roman times to refer to a glazed or unglazed ceramic ware intended primarily for architectural elements and large statuary. The clay or clays from which terra cotta is made are carefully selected for certain definite properties. In many cases the clay body finally used is a mixture of different clays from widely scattered sources, all carefully measured and combined from exact formulas. A terra cotta clay body frequently includes sand or grog to help reduce shrinkage and subsequent warpage during manufacture. Terra cotta can be coated with white, black, buff, or colored glazes. In ancient times, prior to fifteenth-century development in Italy, terra cotta was unglazed but had a range of earth tones resulting from natural pigmentation, such as iron, present in the clay deposit. Thus, the earth's own coloring added variety to the molded clay surface before glaze technology had been developed.

COLOR AND DESIGN IN TERRA COTTA

Polychrome glazed terra cotta was first introduced into American architecture in 1900 by McKim, Mead, and White in New York's famous Madison Square Presbyterian Church. Even with the enormous success of this outstanding early example, strongly colored terra cotta remained an exception rather than the rule for the next two decades. Just prior to 1920, after a prolonged period of monochromatic terra cotta cladding, an upsurge of interest in color developed.

Much of the architecture of the 1910s that we think of as monochromatic did, in fact, use colored terra cotta. The ornament on the Woolworth Building (1913) includes terra cotta blocks with blue, yellow, and green glazes. These colors, however, served primarily to articulate the building's architectural details, and they blended into the white Gothic cladding. During the late 1910s and early 1920s, this understated role of color was gradually replaced by a bolder palette, permitting color to be used for its own decorative value.

This attitude toward color – that it should stand out and attract the viewer's attention-became widespread. Colored terra cotta was introduced as an emphatic element in entryways, street-level facades, cornices, and lobbies. An enormous range of glazes, including metallic lusters, vivid yellows, cobalt blues, or fashionable "deco" shades such as lime green, lavender, and ebony, was developed.

Although terra cotta appeared in a highly visible form in Art Deco architecture of the 1920s, during this same period another very different approach to the use of terra cotta was widespread. It enabled numerous architects to continue to design in traditional historical styles. They recognized the advantages of terra cotta and chose to use it not only because it was fireproof, lightweight, easily available, and economical, but also because it convincingly mimicked far more expensive building materials. Through careful choice of glazes, terra cotta could be disguised to look like granite, limestone, or marble, and only the most astute building professional could recognize what the material actually was. The manufacturers of terra cotta stressed the potential for varied surface finishes and introduced glazes like "granitex" that re-created the color and texture of real granite. The architects who chose to use terra cotta in this way – as essentially a substitute material – usually relied on Greek, Roman, or Gothic styles of design.

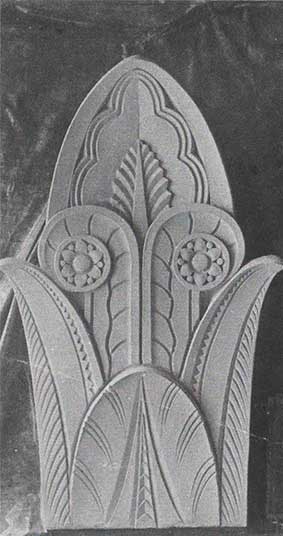

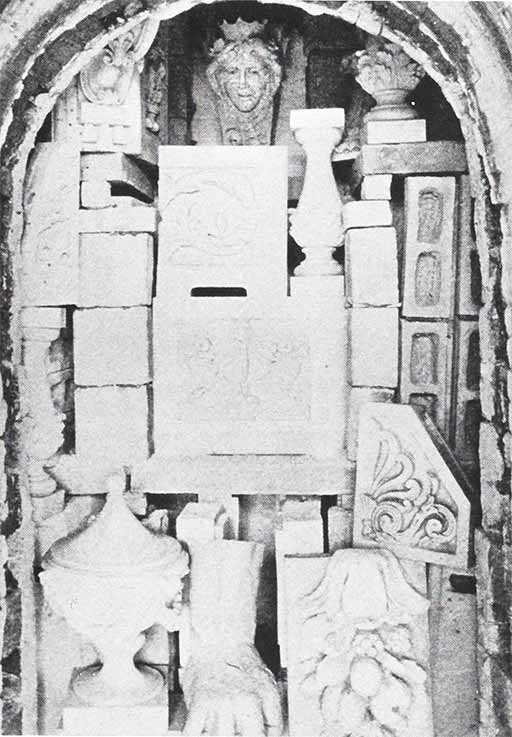

Recently discovered photographs of the work of Isadore Kaplan clearly illustrate this dual nature of terra cotta throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. Kaplan, a trained sculptor, served as a modeler for the New York Architectural Terra Cotta Company from the early 1920s until 1931. These photographs of architectural ornaments that he modeled for this company show that he alternated between traditional historic ornament and fashionable Deco motifs. Two specific examples, made within weeks of each other, include details from 30 Beekman Place (1928-1929, George Pelham) and from 944 Park Avenue (1928-1929, Joseph Unger). The former is in the Italian Renaissance style, while the latter is typically Art Deco.

Recently discovered photographs of the work of Isadore Kaplan clearly illustrate this dual nature of terra cotta throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. Kaplan, a trained sculptor, served as a modeler for the New York Architectural Terra Cotta Company from the early 1920s until 1931. These photographs of architectural ornaments that he modeled for this company show that he alternated between traditional historic ornament and fashionable Deco motifs. Two specific examples, made within weeks of each other, include details from 30 Beekman Place (1928-1929, George Pelham) and from 944 Park Avenue (1928-1929, Joseph Unger). The former is in the Italian Renaissance style, while the latter is typically Art Deco.

The use of terra cotta for eclectic ornamental styles as well as for the streamlined look of Art Deco continued to be common throughout this period. The demands of Deco for a new, flatter look led to the introduction of machine-extruded terra cotta units. These pieces, compared to the earlier, more sculptural ones, required less hand labor and could be produced more economically. Not only was the terra cotta less expensive, but quick installation resulting in reduced construction costs multiplied the economic benefits. The versatility of terra cotta enabled it to become part of the growing skyscraper style that gained popularity in the years to come.

Until 1930, the fifty-two-story terra cotta Woolworth Building was the world's tallest building. However, the rapidly increasing size of skyscrapers brought an end to the use of terra cotta as a cladding material for the structure's entire exterior surface. Instead, glazed terra cotta was introduced as a decorative element in entrances, facades, and lobbies, often in particularly innovative ways. During this period, brick skyscrapers combined it with glass, metal, mosaic tile, and even colored mirror.

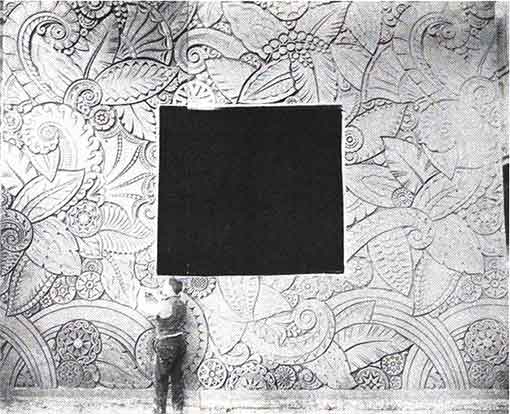

In New York's Chanin Building (122 East 42nd Street, 1929, Sloan & Robertson), a terra cotta floral motif surrounds the third and fourth stories, while marble, copper, and bronze are used just below for additional embellishment. Because the earliest use of American terra cotta was in brick buildings, its return to them in the 1920s and 1930s is an interesting phenomenon, showing the material going full circle. Whereas terra cotta was used in the 1880s to imitate stone or metal details in the masonry buildings, terra cotta of the 1920s was intended to be eye-catching – the best architects of the period exploited its varied and unique decorative qualities.

TERRA COTTA IMAGES AND ICONS

The glorification of business and commerce in the 1920s and the realization that industry and advertising were potential sources for design gave architects new sources for their images. Terra cotta motifs frequently reflected the function that a particular building served. Through these

varied symbols, terra cotta helped to capture the wit and humor of owners and architects and has added whimsy to many of our buildings.

Various corporations sought to express their identity through the buildings that housed them. The American Telephone and Telegraph Company built one of the earliest and finest Art Deco skyscrapers at 140 West Street, in lower Manhattan. The designers, Voorhees, Gmelin, & Walker (1923-1926), used the image of the bell surrounded by grapevines as a central icon for their building. What more appropriate associations with the telephone could there be than a grapevine and a bell?

Large chain stores such as Kress, Woolworth, and A.S. Beck designed simple monochromatic but recognizable building images that appeared on main streets throughout the country. A neat, clean, streamlined look with stylized Deco motifs was characteristic of these three companies, and each was easily identifiable from its characteristic terra cotta logo.

On the other hand, some of the most amusing examples of iconography were one of a kind. The Radio Corporation of America (570 Lexington Avenue, New York City, Cross & Cross), now the General Electric Building, incorporates a terra cotta phonograph needle, radio waves, and stylized human figures in the exterior facade and top of the building. To draw further attention to the building, it is lit at night and the outlines of these images are highlighted. This outstanding building is an example of the designs of the late 1920s and early 1930s that combined contemporary style with new building code regulations to create some of the city's most spectacular new structures. The 1916 New York zoning ordinance required setback design. Floodlights could easily be placed in these setbacks for extremely effective night lighting. William Lockhardt, of the National Terra Cotta Society, stated in 1931, “… today we lean heavily on the proven superiority of terra cotta for buildings to be given exterior night illumination.”2 He adds, “… we may be glad to know that by facing a building with terra cotta we may increase the light in the street over fifty percent as compared with that resulting from the use of certain other architectural materials.”3

During the last few years it has become fashionable to light the tops of historic and contemporary buildings in many American cities. Many illuminated buildings in New York are actually a reincarnation of the original dramatic lighting of the late 1920s and early 1930s. One such example is the Chanin Building, a welcome addition to New York's evening cityscape.

FACTORY FROM START TO FINISH

According to Walter Geer's The Story of Terra Cotta (1920), terra cotta offered a far better reflection of the personality of the architect than any other building material. There was no other material that could be as readily impressed with the conception of the artist as “clay in the hands of the potter.” Architectural terra cotta was not stocked by material dealers; rather, every job was individually executed with special attention paid to each set of structural conditions. “More so than any other architectural product, terra cotta is 'hand tailored' to the finest degree – not simply the embodiment in three dimensions of a set of drawings, but the complete expression of the architectural idea in terms of a certain combination of colors, glazes, surface textures, ornamentation, and other qualities not found combined in other masonry materials.”4 The process of terra cotta production, from the architect's blueprint to the final installation, was a complex and fascinating one.

Each design passed through many hands varying in skill and background from those of the finest European sculptors to those of untrained day laborers. Except for the modelers, who achieved recognition because of their unique skills and the visibility of their efforts, most factory workers labored in anonymity, because terra cotta pieces were rarely signed by individuals or marked by the companies that produced them. Thus we have been left with a clay legacy by largely unknown craftsmen.

Before any claywork began, the terra cotta company produced shop drawings made to an appropriate scale and showing the jointing and construction details. Based on the plans furnished by the architect, the drawings were enlarged by the terra cotta draftsman to allow for the shrinkage of the clay (one inch per foot on average). These draftsmen used a scale or rule 13 inches long, divided into 12 “inches” to ensure that the finished pieces would be the correct size. Following the architect's approval, full-size models were sculpted by the modelers in plaster and/or clay, depending on the design of the particular piece. These were then used to produce plaster molds for the pressing shop.

In order to prevent warpage during firing, the molds, and consequently the terra cotta pieces pressed from them, were kept relatively small. Thus, a large ornament would often be cut into several sections, each of which would be used to make a separate mold. Sensitive cutting and careful attention to the original design of the ornament was important in minimizing the visibility of the sections in the final installation. The plaster molds, usually consisting of four separate sides and a bottom, were bound together with wire bands so that clay could be pressed into them. A typical piece of terra cotta had 11/2 inch walls and was about 4 to 6 inches deep. The pressed pieces had hollow backs with interior partition walls of clay to provide additional strength. Small holes were usually made in these walls so that metal fittings used to anchor the terra cotta pieces to the building could be inserted.

An alternative to hand pressing was extrusion. A steel die was cut to match the specific profile of the form and clay was squeezed through the die in an extruder. Machine extrusion allowed for mass production of terra cotta veneer and terra cotta intended for fireproofing. The low-relief Art Deco designs of the 1920s took advantage of this capability, and extruded veneer was widely used.

After a piece of terra cotta was removed from the mold or extruder, it was allowed to stiffen and dry enough to support its own weight. The final finishing of the damp piece involved smoothing the edges (workmen in one company always used the leather tongue of a shoe for this task), repairing imperfections, and removing any plaster particles remaining from the mold. Additional drying time was required before the piece could be glazed or fired, the length of time varying according to the type of piece, its size, and the method of drying used. By 1913, many companies were using humidity dryers to ensure quick and even drying. After the piece was thoroughly dry, the terra cotta was ready to be glazed by members of the spraying department with compressed air apparatus.

Advertising of leading terra cotta manufacturers in trade publications of the period boasted production time of only

seven days using stock items with readily available molds. Fulfilling this promise required a highly organized and efficient factory and fully involved draftsmen, estimators, and even bookkeepers in the operation. Though this may sound mechanized and industrialized, the product remained essentially handmade. In contrast to other industries, the role of machinery in terra cotta production prior to the 1940s remained peripheral. To produce terra cotta successfully required trained workers who, like potters, understood the nature of the material and its foibles. A true terra cotta worker, it has been claimed, had clay in his veins.

The ties between the American terra cotta and pottery industries are many. The overlap can be seen in wares available in the early terra cotta catalogues, many of which offered garden pottery, statues, and benches. At a later period some companies even had tableware divisions. The Gates Potteries, which produced an art line known as Teco Ware, was an offshoot of the American Terra Cotta and Ceramics Company founded by William Day Gates in 1881 to produce drain tile, brick, and architectural terra cotta. This Chicago company experimented with clay and glazes for architectural uses but, in addition, tried through these experiments to create pottery that would fulfill their ideal in form, color, and surface texture. Some of the most unusual designs were the creation of Fritz Albert and Fernand Moreau, both chief modelers for the American Terra Cotta and Ceramics Company. By 1904 Albert actually divided his time between the terra cotta factory and the pottery.

An interesting example of the joint efforts of the terra cotta industry and the art potteries is that of the original New York City subway system built between 1901 and 1904. The Atlantic Terra Cotta Company was hired to manufacture pieces for numerous stations along with the Grueby Faience Company in Boston, the Mueller Mosaic Company in Trenton, the Rookwood Pottery Company, and the American Encaustic Tiling Company, both from Ohio. There are also important links between the terra cotta companies and the manufacturers of other industrial clay products for laboratories, bathrooms, roofs, chimneys, and sewers. Production of these diversified but related products was often vital to the financial stability of the terra cotta companies.

THE BUSINESS OF TERRA COTTA

The terra cotta industry recognized the need to organize as early as 1886 when the Brown Association was formed by New York companies. It was followed by the Manhattan Materials Company in 1896 and the Terra Cotta Manufacturers Association in 1902. Finally, in 1911, the National Terra Cotta Society, which remained active until 1934, was created. A combination of factors accounts for the eventual decline of the National Terra Cotta Society as well as for the declining use of terra cotta in the 1930s. The president of Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Company, E.V. Eskesen, wrote in the Bulletin of the American Ceramic Society, 1932, “The dream of the modern architect is to build houses entirely out of metal, glass, and cement…In this construction, brick, tile, or terra cotta has no place.”5 These new materials were truly mass-produced machine products. They were economical and available quickly in very large quantities. In contrast, terra cotta manufacture, requiring hand finishing, time for proper drying and firing, and care in shipping and installation, was too labor intensive and consequently too costly to remain in widespread use. Ironically, in the 1880s, economy was one of the selling points of terra cotta. It was labor saving in comparison to the laboriously carved stone ornament that it was intended to replace.

The influence of European architects like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who introduced a clean, unadorned look into building aesthetics, led to a further decline of interest. Most felt that the sleek look of transparent glass and metal could not be imitated by terra cotta. However, this was debated by William Lockhardt, of the National Terra Cotta Society, who stated, “With the development of new architectural styles and the creating of an entirely new system of ornament, metals are playing a part of constantly increasing importance in architecture. Metallic finishes are attained easily in terra cotta, with textures which would be difficult or impossible to obtain in the metals themselves. This is important for effective floodlighting. Furthermore, expensive polishing is not needed to maintain their brilliance. Simple washing with soap and water will restore the metallic surfaces to seeming newness.”6

Terra cotta could readily achieve the unornamented lines and the flat surfaces of the prevailing architectural taste. Because these new pieces were extruded, they could be made in large sizes. Consequently, by the late 1920s, terra cotta was able to offer the architecture of the period solid colors on a scale previously unimagined. The thirty-eight-story deep-green Carbide and Carbon Building in Chicago, the turquoise blue Pelisser and Eastern Outfitting buildings in Los Angeles, and the thirty-seven-story blue-green McGraw-Hill Building in New York, are just a few examples of the material's wonderful potential. Nonetheless, the power of fashion blinded architects and clients to these new opportunities, and the fear of being old-fashioned led many former users to reject terra cotta.

One positive outcome of the Depression for the terra cotta industry was the widespread construction of public buildings through WPA programs. Artists, craftsmen, and designers joined forces in efforts to enrich the buildings of this period. Terra cotta was used for large-scale murals as well as for architectural ornament in numerous small public buildings. Large scale terra cotta works included the sculptures, fountains, and structures of the 1939 New York World's Fair. Post offices throughout the New York area as well as important buildings like the Municipal Building in Washington, D.C., also used terra cotta for exterior ornament and murals.

World War II brought new hardship to this already struggling industry. Peter Olsen, President of the Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Company, wrote in 1944, "As to the factory, we are extremely limited in manpower and for that reason cannot work very efficiently. We have men who are one day working in the pressing shops, and the next day grinding and perhaps the day following are drawing kilns…This would all be overcome by having say 12-15 of our old skilled men back.”7 Following the war, the terra cotta industry suffered an additional blow because enough time had passed to show the serious problems that resulted from improper installation and maintenance of terra cotta buildings. Adequate knowledge of the properties and possibilities of all building materials is essential. Satisfactory performance of masonry generally depends upon three factors (apart from the nature of the particular masonry material): adequate support, proper anchoring or bonding, and protection from water infiltration. Although the durability of terra cotta had long been recognized, these three factors – particularly water seepage – caused a variety of material failures and its durability came under scrutiny.

By 1947 only seven companies remained in operation, compared to twenty-four in 1924. These companies tried to adapt terra cotta to the continuing changes in the building industry and to address the questions of durability that arose. They did this, in part, by forming the Architectural Terra Cotta Institute in 1947. The member companies included American Terra Cotta Corporation in Chicago, Denver Terra Cotta Company in Denver, Federal Seaboard Terra Cotta Corporation in New Jersey, Gladding, McBean & Company in San Francisco, O.W. Ketcham in Philadelphia, Northwestern Terra Cotta Corporation in Chicago, and Winkle Terra Cotta Incorporated in St. Louis. Daniel Barton, the president of O.W. Ketcham, was the last president of the Architectural Terra Cotta Institute, which disbanded in 1959. Mr. Barton felt that the terra cotta industry should not have tried to compete with the capabilities of other, newly developed materials but rather should have continued to emphasize the strength of terra cotta as a unique ornamental material. Most companies, which retained their sense of craftsmanship as well as their sense of pride and prejudice from the past, did not comfortably adapt to the nearly totally mechanized climate of the 1950s and 1960s.

Only one manufacturer, Gladding, McBean & Company, continued to be active during these years. Established in Lincoln, California, in 1875, it has remained in operation, surviving the 1950s and 1960s by producing large quantities of sewer pipe along with occasional terra cotta projects. The outlook for Gladding, McBean & Company began to brighten in the late 1970s, and over the last ten years they have produced various types of architectural terra cotta to fill nearly six hundred job orders. Not only has their factory been kept busy, but several new companies manufacturing architectural terra cotta have formed in recent years in various parts of the country. These include Boston Valley Terra Cotta in Hamburg, New York, MJM Studios in South Kearny,

New Jersey, and Superior Clay Corporation in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Ludowici-Celadon, Inc., in New Lexington, Ohio, nationally recognized for its fine rooftile, has begun to produce architectural terra cotta as well.

This renewed interest can be attributed to two factors. First, the recognition of our architectural heritage through the field of historic preservation has led to a great increase in enlightened restoration and maintenance of older buildings. Friends of Terra Cotta, a national nonprofit preservation organization, was formed in 1981 with the purpose of promoting education and research in the history, preservation, and use of architectural terra cotta and related ceramic surfaces. Since terra cotta was such a popular building material, many older structures used it for cladding or in combination with brick. The vast majority of architectural terra cotta presently manufactured is for replacement pieces used in the restoration of historic structures. Serious interest in historic preservation developed in America during the years following World War II, as the building boom began to threaten historic structures. In a 1941 study, 6,400 historic buildings were identified nationwide, but by 1963 only 3,840 of these remained. Continuing growth of the preservation movement on a city, state, and national level is encouraging, but at times it is difficult to reconcile the slowness of this growth with the rapidity of massive, new development projects across the country.

A second factor leading to terra cotta's growing popularity is the reintroduction of color, surface pattern, and ornamentation into today's architecture. After many years of steel and glass structures, architects are now using a wider range of materials and have also begun to incorporate many rich and varied elements into their buildings. This has led to an exploration of the unique options that terra cotta offers. Perhaps the most unusual of these is a permanent colored glaze surface that is available in many hues, textures, and surface finishes. A number of interesting new projects using terra cotta have been completed in the last few years. One particularly innovative example by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates, a firm that has used terra cotta in a number of projects, is the Ohio Theatre Expansion and Arts Pavilion in Columbus, Ohio. The decision was made to use plum-colored glazed terra cotta for a three story high interior wall in the newly created lobby for the exuberant 1928 theater by Thomas Lamb. Since terra cotta was historically used only as an exterior building material, this application opens new territory for terra cotta in contemporary design.

Both the Friends of Terra Cotta and the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., have offered artists and architects opportunities to investigate contemporary uses for architectural terra cotta. In 1988, the Friends of Terra Cotta held an exhibition called “Firing the Imagination: Artists and Architects Use Clay” that included work from six collaborative teams of artists and architects. In 1985 a Terra Cotta Competition sponsored by the National Building Museum resulted in a traveling exhibition. Further experimentation with terra cotta will continue as clay artists become aware of the long-standing role that clay has traditionally played in architecture. Terra Cotta manufacturers welcome the opportunity to develop original designs, thereby reestablishing a collaborative relationship among craftsmen, artists, and architects that has long existed in the industry.

FOOTNOTES

- Economist, Volume XII, August, 1894, p. 206.

- William Lockhardt, "Architectural Terra Cotta," General Building Contractor, January 1931, p.1.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. p. 3.

- E.V. Eskesen, Bulletin of the American Ceramic Society, 1932.

- Lockhardt, p. 5.

- Letter, Peter Olsen, 1944.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berryman, Nancy D. and Susan M. Tindall. Terra Cotta: Preservation and Maintenance of an Historic Building Material. Chicago: Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois.

Darling, Sharon. Chicago Ceramics and Class: An Illustrated History from 7871 to 7933. Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1979.

Ferriday, Virginia Guest. Last of the Handmade Buildings: Glazed Terra Cotta in Downtown Portland. Portland, Oregon: Mark Publishing Co., 1984.

Impressions of Imagination: Terra-Cotta Seattle. Seattle, Washington: Allied Arts of Seattle, Washington.

Page, Charles Hall & Associates, Inc. Splendid Survivors. San Francisco, 1979.

Sites #18: Architectural Terra Cotta. New York: Lumen Inc., 1986.

Tindall, Susan and James Hamrick. American Architectural Terra Cotta: A Bibliography. Monticello, Illinois: Vance Bibliographies, 1981.

LIST OF TERRA COTTA MANUFACTURERS

- Gladding, McBean & Company, Box 97, Lincoln, CA 95648.

- MJM Studios, River Terminal, 100 Central Avenue, Bldg. #89, South Kearny, NJ 07032.

- Boston Valley Terra Cotta, 6860 Abbott Road, Hamburg, NY 14075. Ludowici-Celadon, Box 69, New Lexington, OH 43764.

- Terra Cotta Productions, Superior Clay Corporation, 1425 Sheffield Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15233.