Access to Pots: A Guide to Using Museum Collections

Web editor's note: This is an abbreviated version the article published in June 1983. Some of the information about museum collections may not be up to date.

With this article, Studio Potter begins a new, ongoing series on collections of ceramics housed in museums and art galleries in the United States and on how potters may gain access to those collections in order to amplify and enrich their own work with clay through study and handling of objects made by their predecessors in the field. While the series should prove useful to the person who simply wants to know what to expect to see in the public galleries during a casual visit, it is intended specifically to guide the potter who wants to handle pots in storage. Most museums, especially older ones with large cumulative collections, exhibit only a fraction of their holdings at any one time. Although this fact is sometimes cited as criticism of a policy of "secrecy," in reality it is a boon to the potter since pots are more readily removed from storage cupboards than from exhibition cases. Indeed, most museums are ready and willing to show their stored collections to visitors, given sufficient notice. While the training of some groups of specialists, such as art historians, includes as a matter of course information on how to work with museums, that of potters often does not. This series hopes to remedy that situation.

The key for the potter lies in knowing the right way to approach the museum, and the first rule is to make an appointment. Recently one acquaintance complained to me that she had gone to a major museum in a distant city to see a special exhibition and, while there, had decided to try to see some pots in storage as well. She approached the information desk but was firmly discouraged from even trying to contact the curator. She felt hurt, but in fact that information person was protecting the curator, who might have been in the midst of a meeting, racing toward a catalogue deadline, or simply trying to grab a bite of lunch between chores. The easy accessibility of the public galleries of museums tends to give the impression that the museums' private areas - offices and storage - should be accessible on an equally impromptu basis, even though there are few other offices into which one would expect to be able to walk for a similar purpose without an appointment. An appointment smooths the way for everyone. Writing or telephoning a minimum of a week in advance of the desired visiting day gives the museum staffperson time to schedule the visit at a time when the potter can receive undivided attention. (It's no fun rummaging in the storeroom on an empty stomach!)

The key for the potter lies in knowing the right way to approach the museum, and the first rule is to make an appointment. Recently one acquaintance complained to me that she had gone to a major museum in a distant city to see a special exhibition and, while there, had decided to try to see some pots in storage as well. She approached the information desk but was firmly discouraged from even trying to contact the curator. She felt hurt, but in fact that information person was protecting the curator, who might have been in the midst of a meeting, racing toward a catalogue deadline, or simply trying to grab a bite of lunch between chores. The easy accessibility of the public galleries of museums tends to give the impression that the museums' private areas - offices and storage - should be accessible on an equally impromptu basis, even though there are few other offices into which one would expect to be able to walk for a similar purpose without an appointment. An appointment smooths the way for everyone. Writing or telephoning a minimum of a week in advance of the desired visiting day gives the museum staffperson time to schedule the visit at a time when the potter can receive undivided attention. (It's no fun rummaging in the storeroom on an empty stomach!)

When arranging for an appointment, specificity about the the type of pots that the potter wants to see is also helpful. Of course, a wish simply to see some representative types of Japanese pots is fine, if that is the case, but if the potter really wants to study variations of iron glazes, it is better to say so, since meeting that request may require special planning, especially if the ceramics collection is scattered in several storage areas. One way for the potter to be assured of seeing exactly the pots that are most germane to his or her work is to consult the museum records in advance of the appointment time. The typical museum keeps a descriptive card for each object in its collection, and sets of those cards are usually found in the particular department as well as in the registrar's office, where central records are kept. The cards may be arranged according to country of origin or subject matter. Sometimes they even include photographs of the objects.

Museums keep track of objects through accession numbers, and those numbers appear on the objects themselves as well as on all materials related to the objects, including photographic negatives and additional data not recorded on the cards. The potter's own record-keeping should begin with a note of the accession number of any pot of interest seen in a gallery case, in storage, or in a museum publication. It's a lot easier for a staff person to retrieve a pot mentioned by number than to hazard a guess about the identity of "that big blue pot that was on display when I was here ten years ago."

This new series begins with the ceramic collections of the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (The Freer's collection was introduced briefly in Studio Potter vol. 9 no. 1 [December 1980], page 48.) The Gallery, which opened to the public in 1923, houses the collection of Oriental and American art formed substantially by Detroit businessman Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919). The collection, which has been expanded since Freer's death through the trust fund established by Freer and through gifts, now contains over 2500 ceramic objects. Japanese ceramics constitutes the single largest group (over 900), followed by Chinese ceramics (more than 700). The smaller Korean collection, of almost 250 pieces, is especially strong in celadons of the Koryo period (918-1392 A.D.). Ceramics from the various areas of the Near East and the Islamic world together number more than 650. The collection covers the representative types produced between the eighth and the seventeenth centuries and includes a number of key dated pieces.

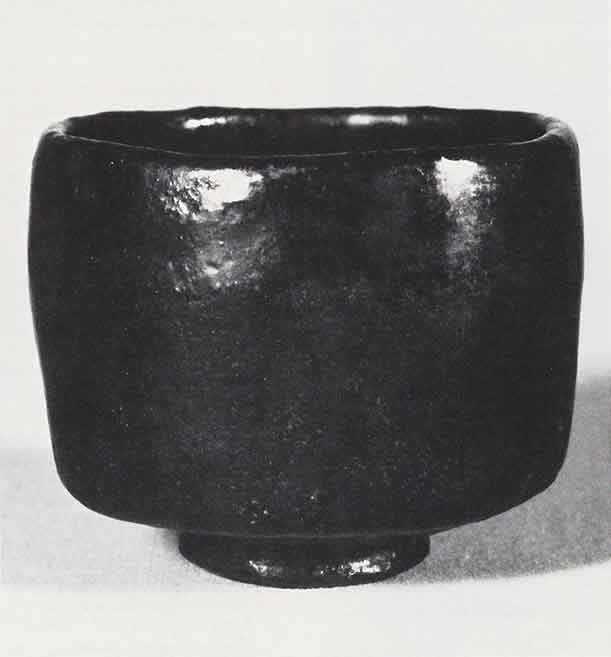

An unusual presence among those Asian pots is the group of thirty-five pieces from the Pewabic Pottery, operated by Mary Chase Perry Stratton in Detroit from 1903 to 1965. In the iridescent Pewabic glazes, Freer found affinities to tonalities in American paintings and pastels in his collection as well as to glazes on certain Oriental ceramics. The inclusion of the Pewabic pieces in the Freer's collection is but one instance of the degree to which aspects of the collection reflect a personal, even a period, taste. For the same reason, many of the Edo-period (1615-1868) Japanese ceramics are types unknown in more recent American collections, since Freer responded to the pots' complex glazes more than to their age, whereas collecting of the past several decades has emphasized pieces from earlier historical periods.

Each ceramic object in the Freer collection is documented on what is called a folder sheet, which consolidates all basic data and curatorial research as well as the opinions of visiting specialists (including potters) who have examined the piece over the decades. In 1921, the New England zoologist Edward Sylvester Morse (1838-1925), better known to potters for forming the remarkable collection of Japanese ceramics now housed in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, was invited to examine the Freer Japanese pots then being prepared for the new gallery. The faithful record of Morse's comments kept on the folder sheets show that he was delightfully outspoken, even at age 84, heaping scathing remarks on pots he believed to be poor examples or recent, but praising the rare one that met his exacting standards with 'It's a corker! A real gem!"