The 1999 International Woodfire Conference: Tradition Is The Future

On April 20, 1741, the General Court of Charlestown, Massachusetts, passed an act, "Relating to Common Nusances," which reads: "For preventing of desolation by fire that may happen by creating of potters' kilns and houses near to dwelling houses and other buildings and the inconveniences and mischief that may accrue to the neighborhood by the offencive and unwholesome smoak and stench proceeding from the kilns when on fire,

Be it enacted,

If any person set up a potters kiln or kiln house in any place within either of the seaport or market towns in this province, other than such place heretofore used for the purpose or as selectmen with two or more Justices of the peace shall design or approve, shall pay 31 pounds-one third to his majesty, one third to the poor of town, one third to informer."1

These early New England "nusances" were fired with wood. In the early 19th century, the great Charlestown potter, Frederick Carpenter, maker of articles of very superior quality and workmanship of a higher character than any before met within this country's manufacture,"2 had a round down-draught wood burning salt kiln. So to did the Dorchester Pottery in the 1880's, whose kiln was 25 feet in diameter holding enough ware at one time to fill one and a half freight cars. The fires were stoked at first with coal and then, for a more intense heat, with wood. The burning took 50 hours, the cooling five days. A wood fired stoneware tradition has existed in America a lot longer than the current revival of interest.

Tradition is either "the action of handing down a belief, a statement or custom by non-written (esp. oral) means from generation to generation," or as "the principles held and generally followed by any branch of art acquired and handed down by experience and practice."3 In pottery terms I think of tradition as an interweaving of time, place, people, materials, technology and style. It is a lineage of sophisticated practices learned on the job through hard work and word of mouth. This applies particularly to woodfiring.

Though seemingly anachronistic, the continued economic viability of these practices bears witness to the power, beauty and flexibility of the tradition. Kim Ellington, a younger potter nearby, who has worked intermittently with Burian Craig, recently built a larger cross-drought kiln complete with side stoking capabilities, and tall enough for kiln shelves, linking the Lincoln County groundhog kiln tradition to the Asian hybrid kilns favored by many contemporary studio potters. Some of the other local potters, such as Charlie Liske, also fire groundhog kilns and continue to take the Lincoln County tradition in new directions.

Yet I wonder, are there degrees of traditionalism? Are some traditional potters more traditional than others? There is no litmus test to determine whether someone is a traditional potter, no seal of authenticity verifying membership. So what is at the core of tradition?

The example of the talented Ben Owen Ill may throw some light on the question. His family has been potting in the Seagrove area since the late 19th century, his grandfather being the eminent Ben Owen who made pots at Jugtown for many years. Ben Ill was first taught pottery by his grandfather, and works on the site of his grandfather's workshop, but he continued his training at East Carolina University where he earned a BFA. Young Ben doesn't use local materials, makes only some shapes traditional to Seagrove, fires a modified groundhog kiln and has gas and electric kilns and operates a flourishing up-to-date studio pottery. Clearly, tradition does not preclude innovation and adaptation. Perhaps place and family are more important than material, technology, and style in determining who we consider part of a tradition.

Yet what is the role of outsiders in this discussion? Was Hamada a traditional potter, or Arakawa? Was Cardew's slipware traditional? In my case, if I cast a critical eye on my own role as an outsider, am I a part of North Carolina's folk tradition? I come out of another tradition, the Leach and Cardew tradition (if indeed it qualifies as a tradition), and am neither North Carolinian, nor folk, and have lived here a mere 17 years. However, most of what I know I learned as an apprentice or empirically in my workshop.

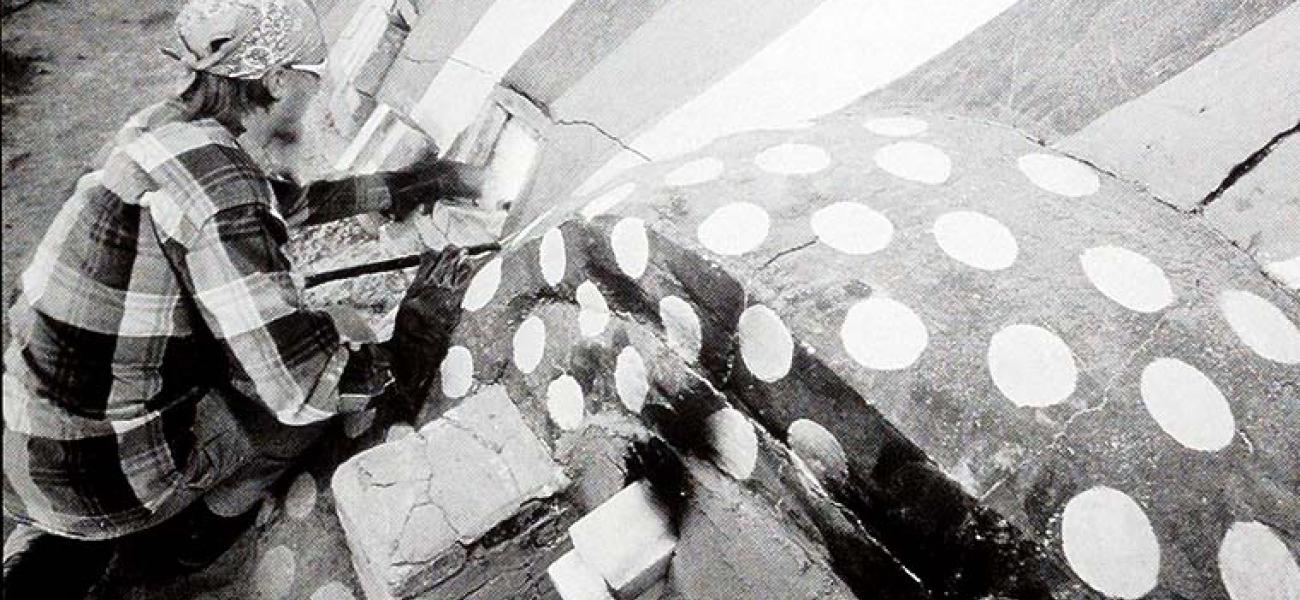

I use two relatively local clays, as dug clays, and one from Tennessee, all of which I refine myself. I have an Alkaline glaze similar to the Lincoln County glaze, but I blow salt on it, as well as on pots that are unglazed. Though my kiln is a 14th century kiln from northern Thailand, essentially it is just a fancy groundhog kiln. The strong ash runs on the sides of some old groundhog fired salt glaze pots are the American equivalent of the ash runs on pots from Tamba, Shigeraki, Bizen, and Echizen. One doesn't have to look Eastward for ash deposits and rugged clay quality. I choose to mix and match elements of both the Alkaline and salt glaze traditions as inspiration dictates. I use stained glass for ornamentation like they do in Lincoln County. I am a jackdaw, picking up the pretty, shiny things that I see here, wanting to make them my own. I'm not beholden to the tradition, but choose to be within its embrace. It is as though I am having a glorious affair with it, taking great pleasure in its company, but with an eye that wanders elsewhere too. Perhaps if I am here long enough I'll make the grade. Or, then again, maybe I am just a "Common Nusance." More to the point, however, by passing all that I know on to my apprentices, my own view of tradition will be modified and continue into the future.

As an outsider I see things within the tradition that people inside may not, everyone has an individual eye. I remember the first time I saw a large collection of Lincoln County pots in a home in Lincolnton. It was a revelation; beautiful, big, slick, drippy green pots everywhere, looking like magnolia leaves after a summer rain. They were unknown, seductive and powerful. I am still under their spell But I cannot and do not want to copy them, I can only make my own. I am not making traditionally inspired pots for ideological reasons (forget romantic Orientalism), but for their tangibility, physicality, and presence.

Time changes tradition, outsiders change tradition, insiders change tradition. A word is spoken, an idea transmitted, and the pots go on forever.

Questions about tradition continue to fascinate me. I will close with some provocative talking points introduced at the Iowa Woodfire Conference to stimulate discussion.

TRADITION IS RADICAL

The prevailing status quo in the Western ceramic world is based on Art School BFA and MFA programs. There are very few traditional potters. To have an MFA is to be normal, to be a traditional potter is to be unusual, radical.

TRADITION IS INDIVIDUAL

At least 90% of the images in the contemporary ceramic press are of non-traditional pots. You can travel anywhere in the US and see the same types of pots at galleries and stores, all made of the same materials, whether in New York, LA, Chicago or New Orleans, Peoria or Paducah. Artistic expression has become standardized, generic.

To be traditional is to be individual.

TRADITION IS EXPRESSION

Within a tradition individual expression flourishes. Give ten traditional potters ten similar lumps of clay and the same pot to make and ten different pots will be made. Each will bear the imprint of individual character and skill. There will be expression even without trying. The expression may not be loud,

but it will be full.

TRADITION MEANS UNDERSTANDING YOUR MATERIALS

To buy premixed clay and glaze materials from suppliers is to have only a partial understanding of them. It is almost a system of potting by numbers; all you have to do is fill in the blanks. To gather and refine your own means to know them from the ground up. Traditional pottery is vertically integrated and complete, non-traditional pottery is fragmented and horizontal. Traditional pottery is a home cooked meal of organic produce, non-traditional pottery is McDonalds.

TRADITION IS EXCELLENT INEXPENSIVE EDUCATION

Teacher ratios at traditional potteries are usually very low, usually no more than three to one. The teaching is constant, personalized, in your face, and thorough. You may even be paid to learn. Art schools are very expensive; the teacher/pupil ratios are poor and the teaching consequently less personal.

TRADITION IS SOMEWHERE

To be part of a tradition is to belong to a place, to have deep roots. Traditional pottery reflects its locality. Non-traditional pottery can be practiced anywhere, it is not rooted to its community so intimately, it is nowhere.

TRADITION LASTS

Tradition is not fashion; it doesn't alter every five minutes like hemlines, or with every new glaze recipe. It is consistent and strong and can last hundreds of years; it is like a redwood tree. And there is a succession from one generation to the next. Non-traditional pottery has a brief beautiful flower which doesn't bear fruit.

TRADITION IS CHANGE

Tradition is adaptive to technology without losing its core. It is a tree trunk out of which new branches grow. To survive, traditional potters constantly modify their operations to fit the times.

TRADITION IS MONEY

Traditional pottery has a higher share of the market relative to its size. It is easier to sell traditional pots than non-traditional pots. Some traditional potters are extremely talented business people, and survive well in a competitive marketplace.

TRADITION IS A WORD

The words tradition, nostalgia, and authenticity can be manipulated to create a very effective marketing strategy. As Burian Craig once said to me, "get all the publicity you can."

TRADITION IS OPEN

Anyone can join, it may take a while, there are examinations to be passed, but an outsider has a chance of becoming part of a tradition.

TRADITION IS THE FUTURE

Traditional pottery is not going to die out, it has lasted along time. People still want traditional pots regardless of the rapid pace of cultural change. Given the right conditions it will continue to flourish.