Carrying Fire Across the Ocean: Our Wood-Firing Journey

In 2005, my husband, Takuro Shibata, and I moved from Shigaraki, one of the oldest pottery villages in Japan, to the Seagrove area, which boasts over one hundred potters, about sixty pottery studios, and approximately twenty active wood kilns with hundreds of years of high-fired pottery-making history. This small town in rural North Carolina is rich in ceramic heritage, serving as both a popular tourist destination and a gathering place for potters, ceramic artists, and historians worldwide. Two years after we came to Seagrove, we purchased property in the historic Seagrove area and established our own pottery business, Studio Touya, renovated an outbuilding into a rustic studio and a small house into a sales shop, and built a Shigaraki-style anagama kiln with additional chambers, and also a small bourry-box wood kiln, to use them to fire our pots. We focus on making functional, Japanese-style handmade pottery and also large-scale sculptures, made of North Carolina wild clays, Japanese traditional simple glazes, and the use of wood-firing techniques.

Journey from Shigaraki to Seagrove

My journey in ceramics began in 1990, when I entered Okayama University in Japan as a freshman majoring in art and craft education. Among the various disciplines, ceramics initially felt the most challenging, which motivated me to work diligently and ultimately led to earning a master’s degree in ceramic art education from the same institution. During this time, my deep interest in wood-fired ceramics was shaped by exposure to Bizen ware, produced near Okayama City, where my university was located. I was deeply impressed by Bizen’s uncompromising approach, where they rely solely on local raw clays and wood firing. As an extracurricular pursuit during my studies, I connected with Bizen potters, assisted in wood firings and pottery festivals, and learned directly from their daily lives as professional makers. These experiences planted early questions about how I might one day follow a similar path. My fascination deepened during an artist-in-residence program at the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park. It was there that I was profoundly struck by the raw beauty of traditional Shigaraki ware, crafted from the region's coarse, untamed clay and fired in ancient anagama kilns and noborigama kilns. This powerful encounter confirmed my commitment to ceramics as a profession, setting me on a path to explore my own artistic voice as a potter, though the exact direction was still unclear.

.

.

Meanwhile, Takuro earned a degree in applied chemistry at Doshisha University in Kyoto and was working as an engineer in his hometown of Osaka when, in 1997, he seized the opportunity to apprentice at one of Shigaraki’s oldest family-run pottery studios. For a year, he wedged clay, cleaned the studio, and delivered pots to wholesale galleries. The apprenticeship also gave him close access to many potters and ceramic businesses in this historic pottery town, providing invaluable, hands-on knowledge of the field. Takuro and I met through our pottery-related work, eventually married, established a studio, and began working as independent potters in Shigaraki. We were very young and had very little money, yet we carried ambitious dreams for the future.

In 2001, a Rotary International Scholarship enabled me to study at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, prompting us to close our Shigaraki studio for two years and relocate to Massachusetts. During this time, we had numerous opportunities to visit wood kilns and participate in firings throughout the Northeast, including Chris Gustin’s anagama, Malcolm Wright’s waritake-style (split bamboo–shaped) wood kiln, the noborigama at Peters Valley School of Craft built by Rock Creek Pottery, Peters Valley’s anagama – constructed by Japanese potter Katsuyuki Sakazume and one of the oldest anagamas in the United States; as well as Jeff Shapiro’s anagama and Peter Callas’s anagama. Through these experiences, we recognized the strong Japanese influence within American wood-fired ceramics while also observing meaningful differences in kiln design, philosophy, and approach compared to our experiences in Japan.

At the conclusion of my studies at UMass-Dartmouth, Takuro and I were invited by Randy Edmonson, professor emeritus of ceramics and an anagama-firing potter, to give a workshop at Longwood University in Farmville, Virginia. This invitation led to our selection as inaugural artists-in-residence at the Cub Creek Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Appomattox, Virginia. There, we focused on digging red wild clay and firing a large noborigama with a dedicated team that included the executive director, John Jessiman, three fellow resident artists, nearby college students, and local potters. It was during this time that we realized we had found the work we wished to pursue for the rest of our lives as professional potters.

During our residency at Cub Creek, we traveled by Greyhound bus to Seagrove, North Carolina – a vibrant pottery community – to visit wood-fire potter David Stuempfle and his partner, Dr. Nancy Gottovi, whom we had previously met in Shigaraki. Touring the Seagrove area and meeting potters who sustained their livelihoods entirely through their work made a deep impression on us. We had not yet encountered such a tight-knit and enduring pottery community elsewhere in the United States. However, our time there was brief. After completing our programs, we left the United States, traveled through Europe, and returned to Japan.

Back in Shigaraki, we stayed in close contact with friends in the United States. Soon after, Takuro was offered a unique opportunity to help establish a new ceramic research initiative – Starworks Ceramics – located in the town of Star, near Seagrove. This opportunity prompted a life-altering decision: we permanently closed our Shigaraki studio, sold all of our ceramic equipment, and in June 2005 arrived in Seagrove, North Carolina, with three suitcases and our orange Shigaraki cat as our only possessions.

Back in Shigaraki, we stayed in close contact with friends in the United States. Soon after, Takuro was offered a unique opportunity to help establish a new ceramic research initiative – Starworks Ceramics – located in the town of Star, near Seagrove. This opportunity prompted a life-altering decision: we permanently closed our Shigaraki studio, sold all of our ceramic equipment, and in June 2005 arrived in Seagrove, North Carolina, with three suitcases and our orange Shigaraki cat as our only possessions.

Takuro immediately began building the Starworks Ceramics Materials and Research project under a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The project’s mission was to research local North Carolina materials, process regional clays for pottery, sell ceramic materials and equipment, and strengthen connections within the state’s pottery community. It began with almost nothing – a broom and dustpan, a used laptop computer, and an abandoned 60,000-square-foot warehouse. This ambitious, one-person effort took several years to gain recognition as a distinctive clay business in rural North Carolina. Over time, it steadily accumulated inventory, equipment, staff, and a strong base of supporters.

Today, Starworks Ceramics has become a vital hub for the ceramics community, sustained by Starworks clay produced from locally sourced materials in North Carolina. The project has earned broad support from ceramic artists, pottery studios, art professors and students, educational institutions, and cultural centers. The facility hosts lectures, workshops, artist-in-residence programs, and festivals, and has organized the Woodfire NC conference three times. Over the past twenty years, Takuro’s unwavering commitment to both the local North Carolina pottery community and the wider ceramics field has steadily built Starworks Ceramics’ reputation and impact.

Wood Kiln-Building Project and Pottery Practice Based in Seagrove

Over the years, we have assisted in many potters’ wood firings to gain a deeper understanding of how wood kilns function and how these structures have served as one of the most important tools in the history of ceramics. Through our involvement in numerous firings across Japan and the United States, we observed that many American anagamas incorporate side stoke holes. Traditionally, the Shigaraki style anagama does not include side stoke holes; however, these additions can be effective in raising temperatures at the back of the kiln and in producing intense charcoal koge effects from the stoked wood.

We also noticed that many American anagamas with an extra chamber – or multiple chambers – are often used for salt firing, allowing for surface effects distinct from those of the main chamber. This configuration reminded us of the Japanese sutema (捨て間), an empty chamber located between the anagama chamber and the chimney. According to research by Michio Furutani (1946-2000), author of The Anagama Book and one of the most respected anagama potters in Shigaraki, the sutema helps retain heat within the anagama chamber and allows the kiln to fire more consistently, with less disruption from weather conditions. Following Mr. Furutani’s findings, many potters and kiln builders in Japan adopted the sutema, which is typically left empty. In contrast, in the United States, the chamber behind the anagama chamber is often used as a salt chamber – a practice that was new to us and sparked our interest.

We also noticed that many American anagamas with an extra chamber – or multiple chambers – are often used for salt firing, allowing for surface effects distinct from those of the main chamber. This configuration reminded us of the Japanese sutema (捨て間), an empty chamber located between the anagama chamber and the chimney. According to research by Michio Furutani (1946-2000), author of The Anagama Book and one of the most respected anagama potters in Shigaraki, the sutema helps retain heat within the anagama chamber and allows the kiln to fire more consistently, with less disruption from weather conditions. Following Mr. Furutani’s findings, many potters and kiln builders in Japan adopted the sutema, which is typically left empty. In contrast, in the United States, the chamber behind the anagama chamber is often used as a salt chamber – a practice that was new to us and sparked our interest.

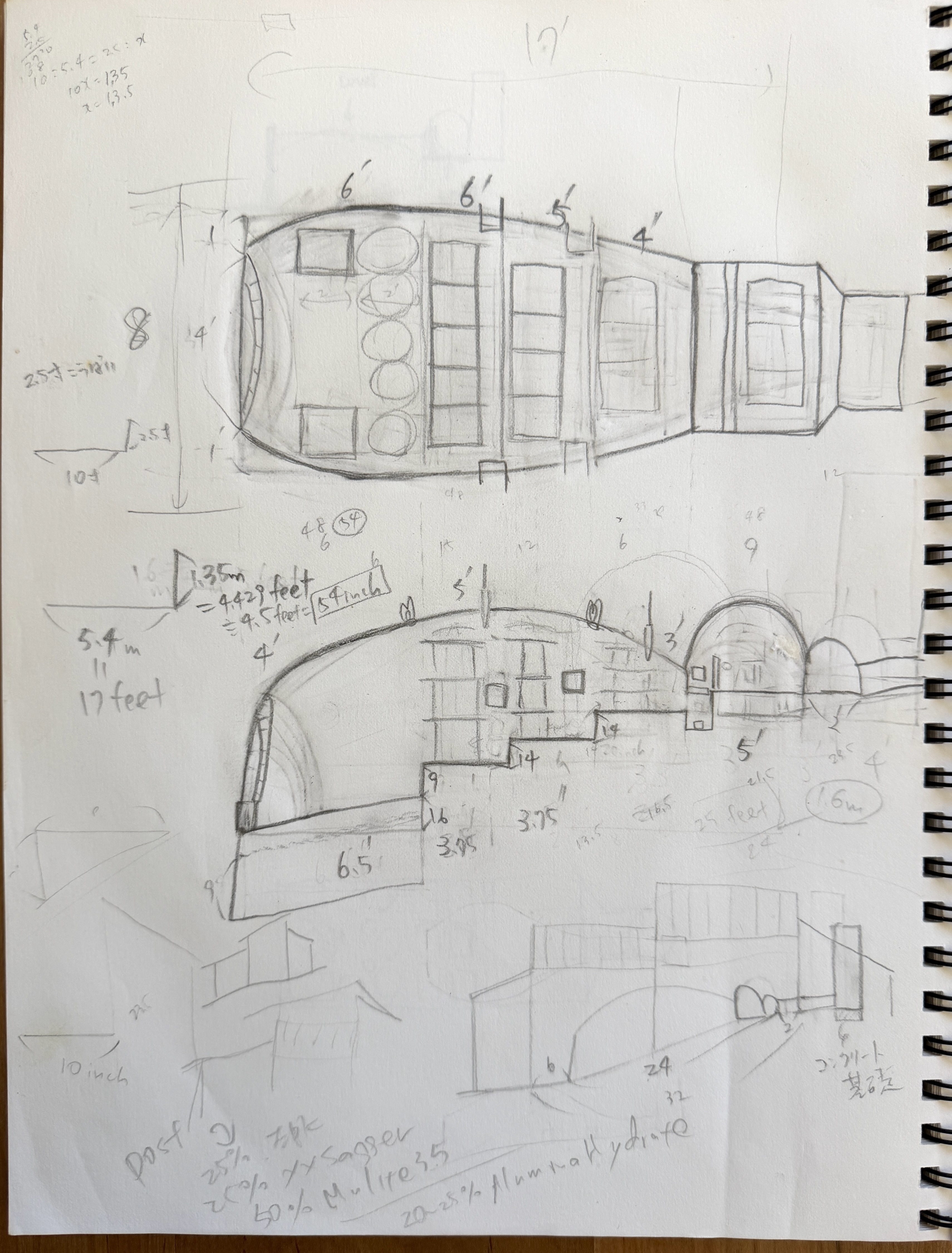

Drawing on these experiences, we designed our kiln as a three-chamber system: an anagama chamber, a salt chamber, and an empty buffer chamber (sutema). We also followed the traditional Shigaraki kiln slope of 2.5–3.5 sun (寸) kōbai (勾配), equivalent to approximately 30 cm of horizontal run for every 7.5–10.6 cm of vertical rise, or a pitch of about 14–19 degrees. We chose the lower end of this range – around 14 degrees – which closely matched the natural slope of our property.

From 2004 to 2005, we participated in the Kanayama Kiln Project at the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park. This project involved excavating an ancient kiln site and reconstructing the kiln based on archaeological models in order to better understand how historical kilns were built and operated. Takuro, who was working as a studio technician at the Ceramic Cultural Park at the time, helped fabricate and use unfired, handmade raw bricks for the kiln’s construction. For the Kanayama project, locally sourced bamboo was used to create the formwork for the kiln arch – a technique we learned through direct, hands-on experience. We later applied this method to our anagama in Seagrove, sourcing bamboo from a neighbor’s backyard to build the arch mold for the anagama chamber. This approach is distinctly different from typical American anagama construction methods.

Working without a large budget, we collected used blocks and bricks from local brick suppliers and industrial sites, purchased local sand, gravel, and fireclay for the foundation and mortar, and hired local carpenters to build simple kiln sheds gradually. Construction began in the spring of 2009. The kiln took two years to complete, built steadily in our spare time – after work, on weekends and holidays, or while our children were sleeping or at daycare. This slow pace allowed us to pause, reflect, read, learn from experienced potters, and work carefully. Laying each brick with intention and precision was deeply satisfying.

Working without a large budget, we collected used blocks and bricks from local brick suppliers and industrial sites, purchased local sand, gravel, and fireclay for the foundation and mortar, and hired local carpenters to build simple kiln sheds gradually. Construction began in the spring of 2009. The kiln took two years to complete, built steadily in our spare time – after work, on weekends and holidays, or while our children were sleeping or at daycare. This slow pace allowed us to pause, reflect, read, learn from experienced potters, and work carefully. Laying each brick with intention and precision was deeply satisfying.

We use the second chamber, located behind the anagama, primarily for tableware. It can be fired independently from the anagama and has a capacity of approximately fifty cubic feet. This wood firing lasts about two days, which is very manageable for the two of us. This chamber will need to be rebuilt soon, as the wall and arch blocks are nearing the end of their lifespan. Building a kiln requires an enormous amount of work beyond making pots, but for wood-fire potters, the process of designing, planning, gathering materials, and beginning a new kiln project is deeply exciting. We also operate a small Bourry-box wood kiln, which we use as a test kiln. In 2015, our friend Andres Allik, an Estonian professional kiln builder, helped us construct this European-style small wood kiln.

We find great pleasure in our simple, rustic studio life: using local clays, sun-drying our pots, collecting rainwater, listening to the wind in the trees, and splitting firewood with our two sons in preparation for the next firing. We strive to minimize machine-made processes, relying instead on our hands, simple tools, natural materials, and the sustainable wood-firing traditions still practiced in the Seagrove area. Our local clays are highly refractory and require firing to cone 10 or higher to fully vitrify. While our methods draw heavily from traditional Japanese pottery techniques and avoid high-tech solutions, they demand extensive preparation, labor, and testing. Unexpected results and errors are inevitable, but each firing provides valuable information that informs and improves the next batch of pots.

Wood-Fire Conferences in North Carolina and New England

As mentioned earlier, Starworks hosted the Woodfire NC conferences in 2017, 2022, and 2025, which served as major gatherings for wood-fired ceramic artists from the US and internationally. These events featured a robust schedule of demonstrations, lectures, panel discussions, and exhibitions. To further enhance the experience, participants had the option of attending pre-conference wood firings at various local Seagrove pottery studios, offering hands-on exposure to different wood kiln types. Seagrove's centuries-long history of handmade pottery, predating electricity and industrial technology, gives its traditional groundhog wood kiln a unique and significant place in American ceramic history. The combined nine-day program of pre-conference activities and the main conference created an immersive and deeply educational environment. Discussions covered a wide range of essential topics within wood firing, including kiln design and construction, appropriate clay bodies, high-refractory materials, historical precedents, technical processes, business strategies, networking, and marketing.

In June 2025, I was invited to present at the 2nd New England Wood-Fire Conference (NEWFC). Visiting Connecticut was especially meaningful, as I had few ceramic-related opportunities to return to New England since leaving Massachusetts at the end of 2002. Trevor Youngberg, a ceramic art teacher, wood-fire potter, and chief organizer of NEWFC, offered participants the chance to take part in three anagama firings at his home studio prior to the main conference. The conference itself was held at Southern Connecticut State University, where Professor of Ceramics Greg Cochenet generously supported the event and provided the venue. It was a profound pleasure to reconnect with the New England conference participants and collaborate with such exceptional artists. These included Kiichi Takeuchi, a wood-fire journey potter and IT specialist at Long Island University; my longtime Shigaraki friend and exceptional anagama potter, Nozomu Shinohara; and the distinguished wood-fire artist, Kayla Noble. This experience was deeply resonant, feeling like a homecoming to the ceramic communities and treasured locations spanning both the United States and Japan.

Wood firing is inherently communal, making in-person collaboration, networking, and shared labor essential to the practice. Conferences and symposiums play a vital role in sustaining this community by facilitating the exchange of knowledge and strengthening professional relationships. While wood-fired ceramics may once have felt like a closed field – particularly for women – it has become noticeably more inclusive in recent years, welcoming a broader range of women, younger artists, and diverse voices.

Wood firing is inherently communal, making in-person collaboration, networking, and shared labor essential to the practice. Conferences and symposiums play a vital role in sustaining this community by facilitating the exchange of knowledge and strengthening professional relationships. While wood-fired ceramics may once have felt like a closed field – particularly for women – it has become noticeably more inclusive in recent years, welcoming a broader range of women, younger artists, and diverse voices.

Working in Two Pottery Cultures: Shigaraki and Seagrove

Shigaraki, a small town steeped in a thousand-year legacy of pottery, was one of the few places in Japan where young potters not born into pottery families could learn how to make a living from clay. At times, we took on mass production for the commercial market – not our preferred path, but a necessary one to support ourselves. While we sold our pots through galleries and wholesale markets, we also balanced various other jobs. Although we were unable to build our own wood kiln in Shigaraki, we embraced every opportunity to participate in wood firings, steadily gaining the knowledge and skills needed to grow as professional potters. These formative experiences instilled in us the confidence to pursue our careers wherever we might be.

In Seagrove, we are able to make the pots we want to create, using local clays, wood ash from our own kiln for making ash glazes, and firewood sourced from nearby sawmills – often repurposing scrap wood as an essential fuel. We value our access to these local resources and work diligently to bring them into balance. This slow, labor-intensive process allows us to create distinctive, handcrafted work, while giving us time to experiment with the region’s beautiful clays and to cultivate a grounded way of life.

Despite the significant differences between Japanese and American pottery traditions, a shared reverence for good clay and wood firing connects these two cultures. We feel deeply fortunate to have lived and worked within such rich and supportive pottery communities.

My Perspective on Wood Firing Practice

Aspiring wood-firing potters must commit to both physically demanding labor and ongoing self-improvement. This dedication often includes studying kiln-building literature, visiting other potters’ wood kilns, actively participating in individual or group firings, pursuing apprenticeships, attending wood-fire conferences, or completing residencies at art centers with access to wood kilns – all while typically balancing other forms of employment. Despite these challenges, there are many paths to gaining practical experience for young potters who demonstrate genuine commitment. In my experience, the global wood-firing community is welcoming, supportive, and demanding, yet generous to those who approach the practice with sincerity and a strong desire to learn.

Establishing a wood-firing pottery studio and sustaining it as a business is an exceptionally difficult endeavor, requiring significant investments of time, space, financial resources, and sustained physical effort. Success depends on a combination of advanced technical skill, intellectual curiosity, and perseverance. Wood firing presents numerous obstacles, including intense physical labor, dependence on weather conditions, energy inefficiency, volatility in the global ceramics materials market, and serious environmental considerations. From a purely practical standpoint, it may appear to be one of the least efficient paths for a working potter.

Yet it is precisely this difficulty that draws us to the process. Through working with beautiful local clays and preparing firewood for each firing, we continue to examine what makes wood firing so compelling. Takuro and I do not pursue wood firing for the perceived added extra value of wood-fired surface, but because we believe the practice embodies strong work ethics and carries authentic stories – rooted in humility, physical engagement, and a deep connection to the ground – within our simple, handmade pottery.