From Clay to Climate – Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery Symposium Review

In her foreword to Sustainable Ceramics, Janet Mansfield wrote, “The practice of craft is perhaps the most sustainable of all the arts. The work is timeless, made to last, often cherished, and passed on through generations in the family. Materials are not wasted but recycled, toxic materials are avoided, disposable products are not favoured, and fashion is not followed thoughtlessly.”[1]

Mansfield, in addition to being a champion of ceramics, was well qualified to extol the virtues of the broader arena of craft. She served as president of the Crafts Council of New South Wales and was an executive member of the Crafts Council of Australia.[2] Yet her foreword goes on to connect the ceramic artist’s particular affinity for sustainable practices because of their handling of clay, the material’s connection to Earth, and the inextricability of Earth with the health of the planet.

Since Mansfield’s untimely death in the same year that this text was published, the state of planet Earth has become more dire. Climate change, species migration and extinction, and human displacement have all reached levels from which there is no return. Furthermore, the current right-of-center political regimes in a number of countries threaten to make matters worse. Despite the seeming hopelessness of our situation, even the smallest effort by craft practitioners towards sustainability is important for the reasons cited by Mansfield.

One recent effort was the staging of the Ceramics and Glass Sustainability and the Environment Symposium by the Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery (CCGG) in Waterloo, Canada. The event, a first for the CCGG, held from January 9 to 10, 2025, drew 50 attendees to the bitterly cold but sunny city, where lectures, demonstrations, and a hands-on activity followed the theme of how ceramics can make a contribution to world sustainment.

Content

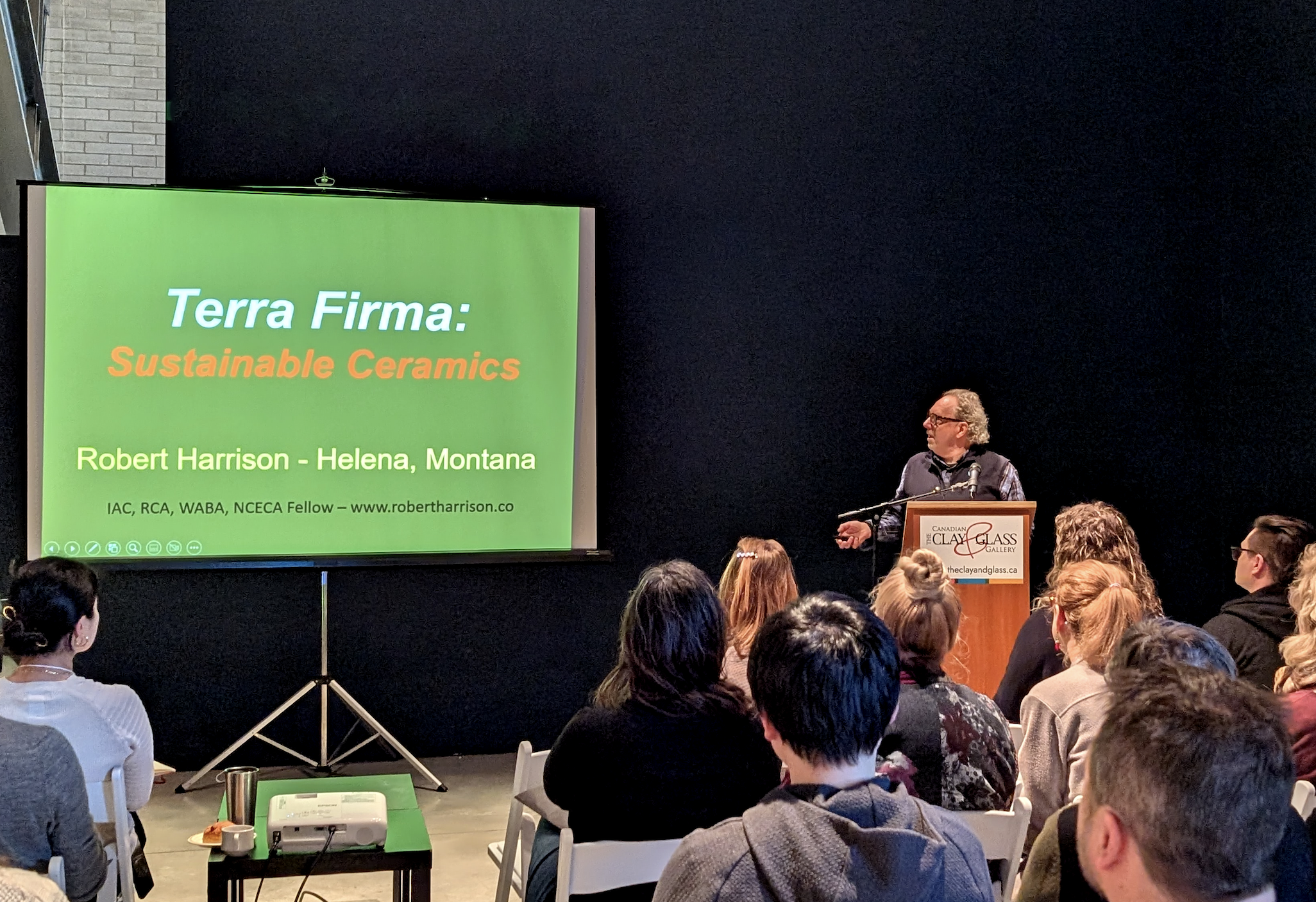

It is not surprising that Peter Flannery, curator at the CCGG and organizer of the symposium, chose Robert Harrison as the keynote speaker. Harrison is the author of the aforementioned Sustainable Ceramics and a ceramist whose practice and career have embraced the reuse, recycle, reduce mantra. His slide presentation highlighted some of his own projects – reuse of bricks, tiles, and pottery shards – as well as the work of like-minded artists, such as Paul Scott, Janet DeBoos, and Bouke de Vries. In addition, he described ways in which makers could adjust studio activities to be greener and leaner in the use of resources. Sustainable Ceramics is still available for purchase and provides a valuable checklist of ways to be conscientious about one’s planet footprint. For example, assess your kiln’s efficiency and efficacy, consider alternative ways of firing, recycle waste materials, use locally acquired materials, ensure your studio is energy efficient, be conscious of water usage.

It is not surprising that Peter Flannery, curator at the CCGG and organizer of the symposium, chose Robert Harrison as the keynote speaker. Harrison is the author of the aforementioned Sustainable Ceramics and a ceramist whose practice and career have embraced the reuse, recycle, reduce mantra. His slide presentation highlighted some of his own projects – reuse of bricks, tiles, and pottery shards – as well as the work of like-minded artists, such as Paul Scott, Janet DeBoos, and Bouke de Vries. In addition, he described ways in which makers could adjust studio activities to be greener and leaner in the use of resources. Sustainable Ceramics is still available for purchase and provides a valuable checklist of ways to be conscientious about one’s planet footprint. For example, assess your kiln’s efficiency and efficacy, consider alternative ways of firing, recycle waste materials, use locally acquired materials, ensure your studio is energy efficient, be conscious of water usage.

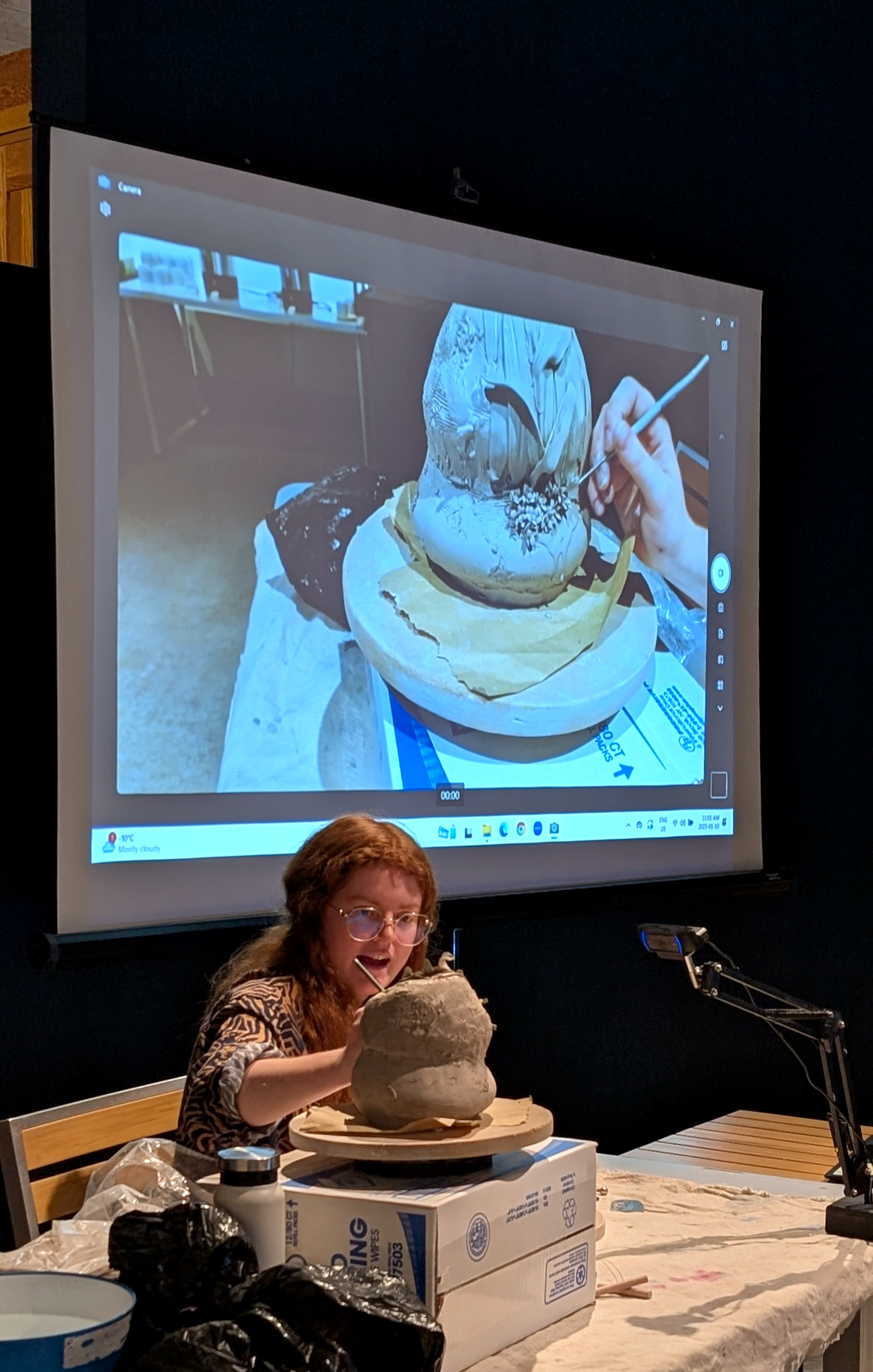

Harrison also draws attention to those creating objects that address sustainability politically. Richard Notkin, whose teapots have been inspired by war and other human mistakes – an overlooked aspect of sustain-ability – states that “I’m trying to make pots that speak of my time, my country, my concerns.”[3]Melanie Barnett gave a lecture and demo at the CCGG that was about her country and her concerns. She grew up on a grain farm in northern Manitoba, where proximity to nature was taken for granted until the marker of spring, frog song, disappeared. Barnett reckons that pesticides, employed to eliminate army worms in agricultural crops, meant that with the frog diet eradicated, the frogs were too. Barnett’s When There Were No Frogs pays tribute to the absent choristers.

Barnett is also fascinated by moss and fungi, often-neglected and literally overlooked life forms, some of which are disappearing due to habitat loss and degradation. She demonstrated how she makes the tiny components of her ceramics and lovingly – as well as tediously – attaches them to the clay base of each sculpture.

Barnett is also fascinated by moss and fungi, often-neglected and literally overlooked life forms, some of which are disappearing due to habitat loss and degradation. She demonstrated how she makes the tiny components of her ceramics and lovingly – as well as tediously – attaches them to the clay base of each sculpture.

Concurrently with the symposium, an exhibition, A Living Palette, was on view in an adjacent gallery space. The declared themes – "global warming, feminism, the male gaze, resistance, and survival"[4] – which Flannery told me were the instigators of the symposium itself, were subtly addressed with the work being more visually appealing than politically charged. Exceptionally, Heather McCaig’s Together We Bloom, a series of flameworked flowers that are emblems for each of Canada’s thirteen provinces and territories, were poignant in their threatened extinction due to loss of habitat. The rendition of the native species – e.g., the Ontario trillium, Saskatchewan red lily, Newfoundland and Labrador pitcher plant – in borosilicate glass replicated the fragility not only of the flowers but of our natural environment. A panel discussion with three of the exhibition’s artists – McCaig, Jess Riva Cooper, and Alejandra Vera – focused on inspiration and process.

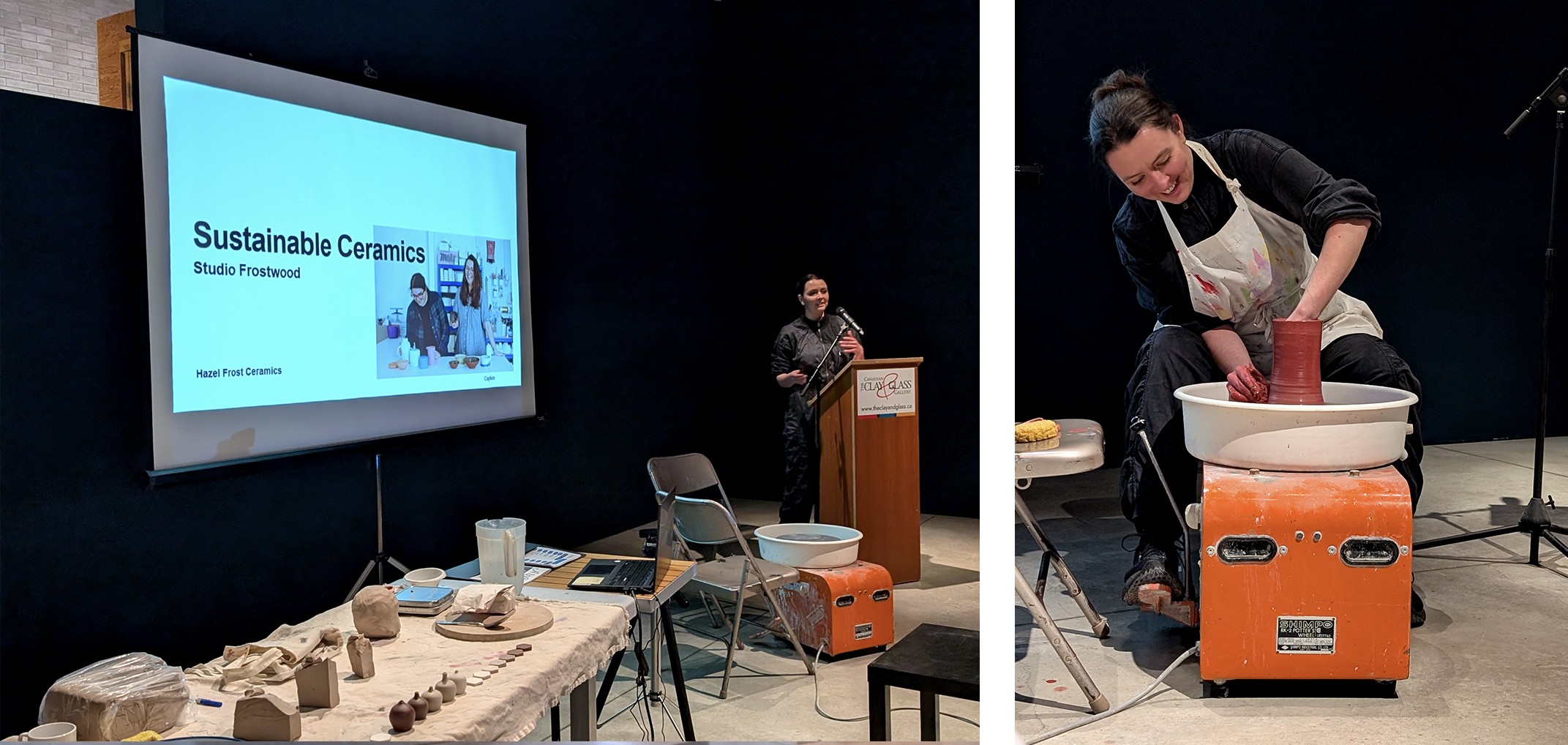

The symposium’s closing speaker, and an appropriate bookend to Robert Harrison, was Hazel Frost. Frost is the co-founder, alongside Natalie J. Wood, of Studio Frostwood in Edinburgh, Scotland. I recommend Frostwood’s website (www.studiofrostwood.co.uk) for a summation of their strategy to embrace sustainability in practical terms. Frost’s presentation in Waterloo reiterated the contents of ‘The Price of Clay’ (on the website), including recycling clay waste, processing glaze and plaster waste, reusing bisque-fired and glaze-fired ceramics, procurement of clay, and kiln usage. Some of these activities required collaborating with other studios, thereby extolling the merits of engagement with the wider craft and design community. One such collaboration, with Stefanie Cheong, a jeweler in Glasgow, Scotland, involved the transformation of glaze waste into a ‘precious’ material for rings.

Frost’s lecture presentation was followed by a demonstration of how powdered waste clay can be incorporated into new objects. Her inclusion in the symposium most directly addressed how the studio potter can introduce sustainability into practice. While there were several other presentations at the CCGG Symposium – Amélie Bélanger and Geneviève Grenier disclosed their attempts to make glass from scratch, and D’Andrea Bowie demonstrated mould making with alginate – their relevance to sustainability was more theoretical than practical.

Conclusion

My presentation in Waterloo, ‘Missing the Earth for the Clay,’ had a hostile reception. My aim in submitting a proposal to speak at the symposium was to provoke potters to look at the bigger picture when considering sustain-ability. I spell sustain-able with a hyphen to complement the philosophy of Australian design critic Tony Fry: spelled this way, it means able to be sustained. By means of statistics and images, I asked the audience to reconsider their use of smartphones, air travel, automobiles and e-tail (particularly Amazon) with the question: is this sustain-able? During the Q and A, I responded to queries that wanted to justify limiting the boundaries around ceramics and sustain-ability.

Fortunately, several attendees quietly told me later that they appreciated my words: I had made them think... which was my intention. However, as one participant pointed out, the sense of entitlement that pervaded the unreceptive Q and A reflected a generational difference – those who have accrued advantages versus those of younger generations who may never know that security. A major ongoing hurdle in all discussions of sustainability is the gap between the haves and the have-nots.

In one of the final chapters of Harrison’s Sustainable Ceramics, he asks journal editors for their views on sustainability. Sherman Hall, former editor of Ceramics Monthly, is quoted:

"I used to think I stood in my basement and made pots. But because of my exposure to all sorts of research and information through my editorial role at Ceramics Monthly, I realise [sic] I stand in the middle of a very large group of people who also stand in their basements making pots, and that what each of us does actually matters. No governmental agency will likely attempt to regulate our carbon footprint … but that is a pretty bad reason to do nothing. In the end, my hope is that studio ceramics today is more sustainable than it otherwise would be without practitioners attempting to improve our collective knowledge base."

That collective knowledge base includes presentations for and attendance at symposiums, workshops, and conferences such as the one at the Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery. It also requires sponsorship by agencies, like the Canada Council for the Arts, in order that such events see the light of day. Sustain-ability should be pervasive in all craft studios and carried beyond them into the community and public arena.

NOTES

NOTES

[1] Janet Mansfield, “Foreword,” in Robert Harrison, Sustainable Ceramics: A Practical Approach (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 6-7, p. 6.

[2] https://www.ccpotters.org/blog/february-17th-2013

[3] https://www.craftinamerica.org/artist/richard-notkin/

[4] Canadian Clay & Glass Gallery, A Living Palette (CCGG, Waterloo: 2024), p. 5.